“The Greed in These Woods”

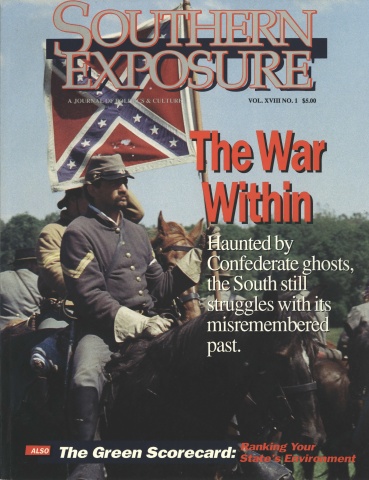

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

Camp Shelby, Miss. — A contest for control of valuable public timber lands in south Mississippi is under way in the De Soto National Forest, and residents with roots going back two centuries say they’re on the losing end.

The U.S. Army and a handful of well-connected developers are vying for the title to prime tracts of pinelands that sprawl across 500,000 acres of rolling hills. In the process, residents say, families are being pushed off their land, wildlife refuges face destruction, and counties are being robbed of millions of dollars in timber revenue needed for schools and roads.

At the heart of the controversy is a push by the military to swap 16,000 acres of grassland it owns in Pinyon Canyon, Colorado for 32,000 of the U.S. Forest Service’s wooded acres in De Soto. Officials at nearby Camp Shelby say the Mississippi National Guard needs the public forest land for tank maneuvers.

But the proposed land swap has unearthed deep resentments among local residents over Camp Shelby expansions, Forest Service mismanagement, and land and timber speculation by businessmen with political connections to U.S. Senator Trent Lott.

“My family has been here since the Indian days,” said a Forest Service employee upset about the land deals but afraid of being identified. “My daddy worked for the Civilian Conservation Corps planting pine trees during the Depression. From when I was born, he taught me the beauty of these woods. In this job, I’ve learned their value. But I didn’t know about the greed in these woods until now.”

Civil War Boys

The De Soto National Forest — the largest in the state — is made up primarily of lands replanted after timber companies exploited the virgin forests around the turn of the century. It also adjoins Camp Shelby, where the military has slowly but doggedly been assimilating local holdings since World War II.

The military already holds a special-use permit to conduct maneuvers over 100,000 acres of the forest, which it bulldozes to make way for 60-ton M-1 tanks and artillery shells. Now the Army wants clear title to the land — part of its nationwide push to add 3.4 million acres of public land to the 19 million acres already designated for military training.

The Forest Service initially balked at the De Soto swap, which would exchange Colorado land valued at $2.3 million for Mississippi pinewoods worth $46.7 million. But Ken Johnson, state director of the Forest Service, now says he is considering the deal “as a result of congressional interest.”

Local residents are furious at being treated as incidental to the wheeling and dealing of federal officials over the large tracts of land. “It’s political,” said Lamar Sims, a Perry County supervisor. “We’ve got 10,000 people in Perry County, and they’re ignoring us. The people I represent get all the guns shooting and the bombs bursting and the F-4 fighters flying over our schools tree-top high, and we’re being ignored.”

Sims fears that if the Camp Shelby land swap goes through, the county will lose much-needed revenues from Forest Service timber sales, a quarter of which go to school and road budgets. Last year alone, timber revenues contributed nearly $2 million to 10 Mississippi counties.

Oscar Mixon, a Perry County resident, said the Camp Shelby swap is part of a land-use trend that often leaves residents on the outside. His own family was forced off their land by the military in the 1940s and moved down the road, only to find themselves in the path of yet another proposed expansion.

“In 1958, the U.S. marshals brought eviction papers and just kicked us off,” Mixon recalled. “I live 10 or 11 miles from there, and now they’re coming down here after us.”

In some places, families are barred from stepping foot on their homesteads by locked gates and signs that warn of live ammunition rounds. Along Mississippi 29, signs caution motorists that live shells may pass overhead.

The tank maneuvers and artillery practice have destroyed thousands of acres of forest land where people once lived. F.H. McRee, whose family watched their home become part of the De Soto National Forest after they lost it to debt during the 1930s, pointed to the place where an errant tank ran through Sweetwater Cemetery a few years back.

“I saw those tombstones laid out on the ground,” McRee said. “Those were the graves of people who settled this area, and that tank just rolled right over them — busted them all to hell. Some of them were Civil War boys.”

Bears and Snakes

Opposition to the land swap also centers on its natural beauty and unique habitat. The land Camp Shelby wants includes the state’s only designated wilderness area — the Leaf River Wilderness — and adjoins its only Wild and Scenic River — the Black Creek.

“I think they picked this area because it’s sparsely populated,” said Walter Sellers, manager of the Leaf River area. “It’s the largest tract they could find with the least resistance.”

State wildlife officials say that if the swap goes through, they may be forced to abandon the Leaf River preserve — the oldest and most popular in Mississippi. Recreation and hunting, they say, simply cannot co-exist with tanks.

Louie Miller, conservation chair of the state Sierra Club, also fears that wildlife will not survive tank assaults and artillery shelling. Miller and other environmental leaders said the transfer would wreck habitat for endangered and threatened species that include the black bear, the Indigo snake, the gopher tortoise, and the red cockaded woodpecker.

Military officials discount the potential for environmental damage, citing federal guidelines that would require reparations. National Guard Adjutant General Arthur Farmer said private land could remain within the tank maneuver area if the swap goes through, and that hunting would still be allowed.

Farmer, however, was stripped of most of his duties in January following revelations that he and two other men bought land adjacent to Camp Shelby. Governor Ray Mabus, who appointed Farmer, ordered him to resign for appearing to use his office for personal gain. Farmer refused, and Mabus stripped him of his command.

Documents also reveal that Farmer and the National Guard have designs on more than the 32,000 acres they have requested. In a letter to U.S. Representative Jamie Whitten, chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, Farmer noted that the Guard eventually hopes to take over 116,000 acres of the De Soto Forest for military use.

Frat Brothers

The military isn’t alone in seeing opportunity in the De Soto woods. The public forest comprises a valuable timber reserve that has caught the eye of real estate investors, several of whom have political connections in Washington.

The Forest Service often trades public land for private property to expand and consolidate its holdings. Sometimes it exchanges land with mature standing timber for clear-cut private holdings that include as much as twice the acreage. Since 1980, the Forest Service in Mississippi has transferred 14,000 acres of woodlands to private individuals in exchange for 23,000 acres.

Such trades are a good deal for developers. They clear their own property of timber, swap the barren land for national forests worth up to $1,000 an acre, cut and sell the public timber, and then resell the stripped land to the highest bidder.

Long before the controversy over the Camp Shelby proposal, residents were chagrined over the private deals. “People have been grumbling about these transfers for a long time, but not doing anything about it,” said I.A. Garraway, who operates a timber business near Janice. “What it boils down to is there are a few individuals fattening their pockets off of public land. I think a federal investigation ought to be done.”

Some of the largest public-private transfers were made to oral surgeon Dr. Bennett York and realtor J.W. McArthur. Both call Hattiesburg home — and both have close ties to Republican Senator Trent Lott. York was a fraternity brother of Lott and a contributor to his campaign, and McArthur’s wife Nevie served on Lott’s campaign staff.

In the largest single transfer to date, York swapped 5,189 acres of private land valued at $3.2 million for 2,796 acres of the De Soto National Forest with standing timber. In all, York has traded a total of 9,218 acres for 4,708 acres of Forest Service land.

Forest Service officials deny that political connections influence land deals. “Let me tell you what they say,” said Joe Duckworth, a De Soto Forest district ranger. “They say you’ve got to be a friend of Trent Lott to get land. But that’s not true. I’ve never gotten a call from Trent Lott, period.”

Joe Clayton, land and minerals officer for the Forest Service in Mississippi, admitted that private individuals interested in making transfers “often let you know how much political influence they have to bolster their case. Lots of them do that.”

But Clayton insisted that such namedropping does not affect land transfers — at least not at the local level. “If political pressure came to bear, it would be further up the line,” he said. “I wouldn’t feel it directly. It would be, for instance, the chief of the Forest Service or the Secretary of Agriculture.”

A spokesman for Lott’s office said the Senator, whose previous House district included the De Soto Forest and who supports the Camp Shelby land swap, has never intervened in public-private transfers.

York and McArthur agreed. “I have never, never asked Trent’s help, nor have I received it,” McArthur said. “I’m not sure he would have intervened anyway.”

Local residents remain unconvinced. “There’s so many facets of these transfers that people don’t know anything about,” said retired Army Colonel Pete Denton. “The more we look into it, the dirtier it gets. Any way you look at it, the people are losing.”

Large Landowners

Whether or not political connections paved the way, local residents say influential landowners like McArthur and York get preferential treatment from the Forest Service. Oscar Mixon said that when he approached the agency about acquiring two 40-acre tracts next to his farm, “they told me in no uncertain terms it wouldn’t be traded. Then J.W. McArthur got it and when I asked why, I was told in so many words that I didn’t have money to deal with the Forest Service in trading land. In my opinion, it’s not right.”

Clayton said the idea is that large

landowners are better able to put together an attractive package to trade with the Forest Service. He said the public has the right to protest any exchange to the Forest Service or their congressman.

But Lewis Posey Jr. of New Augusta, who retired last year from 32 years with the Forest Service, said he doesn’t believe the protests would be heard.

“In my opinion, the transfers I saw weren’t done fairly,” Posey said. “The man that had the political pull got what he wanted. Dr. York got a lot of land that local people couldn’t get. He just picked what he wanted.

“It’s just not giving the local people a fair shake,” he added. “And they’re the ones who helped grow this forest and protect it.”

McArthur, who traded 724 acres of private land for 525 acres of public forest, also thinks he got a good deal. “The Forest Service may have been happy as they can be with the exchanges I made, but I think they benefited me more than they benefited them.”

F.H. McRee wasn’t so lucky. When he tried to get back his family’s land that was sold to the Forest Service in the 1930s, the agency traded it away to a developer instead. McRee was finally able to buy the land back from the developer — but not until the timber had been cut and sold.

Angered by private deals and the Camp Shelby trade, local residents have organized a group called Citizens Against the Swap. Headquartered in the kitchen of retired Colonel Denton, the group has gathered more than 2,000 signatures on a petition asking Governor Mabus not to yield any more forest land to the military.

Residents united once before to save De Soto, successfully opposing a plan to store nuclear waste inside the forest. Their current effort has prodded Mississippi Senator Thad Cochran to suggest safeguards against the abuse of land swaps, and Colorado Senator Timothy Wirth has introduced a bill that would give the military’s Pinyon Canyon grassland to the Forest Service — with nothing in return.

Still, McRee and other residents say they feel betrayed. His daughter Patricia summed up the prevailing mood in an essay she circulated among her neighbors.

“As I look at the map which shows the land to be acquired, I see so many little rectangle shapes with numbers,” she wrote. “Correct me if I am wrong, but do these not represent private lands that have already been ‘terminated’? I think the shape is appropriate. They look like graves or coffins and that’s what they represent to me. Because they are what’s left of the people who settled and lived in this area’s dreams. They are now ‘dead and buried.’ The people can no longer pass on their inheritance because it has been taken away by our own government.”

Tags

Alan Huffman

Alan Huffman is a freelance writer in Bolton, Mississippi. (1990)