This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

New Orleans, La. — Charles Andrews was a newlywed in 1932 when he bought a house for $2,000 in Good Hope, a tiny French Catholic enclave on a bend of the Mississippi River. He knew everyone in town, and together they watched their children and grandchildren grow up and settle down in the quiet community.

A half century later, Andrews and his neighbors lost their homes — not to a hurricane or flood, but to the voracious appetite of GHR Company, the Good Hope Refinery.

“The first security I had, they took it away from me. That’s the way I figure it,” said Andrews, 77, who now lives miles from his closest friends. “I got some neighbors living around here now. I don’t know too much about them.”

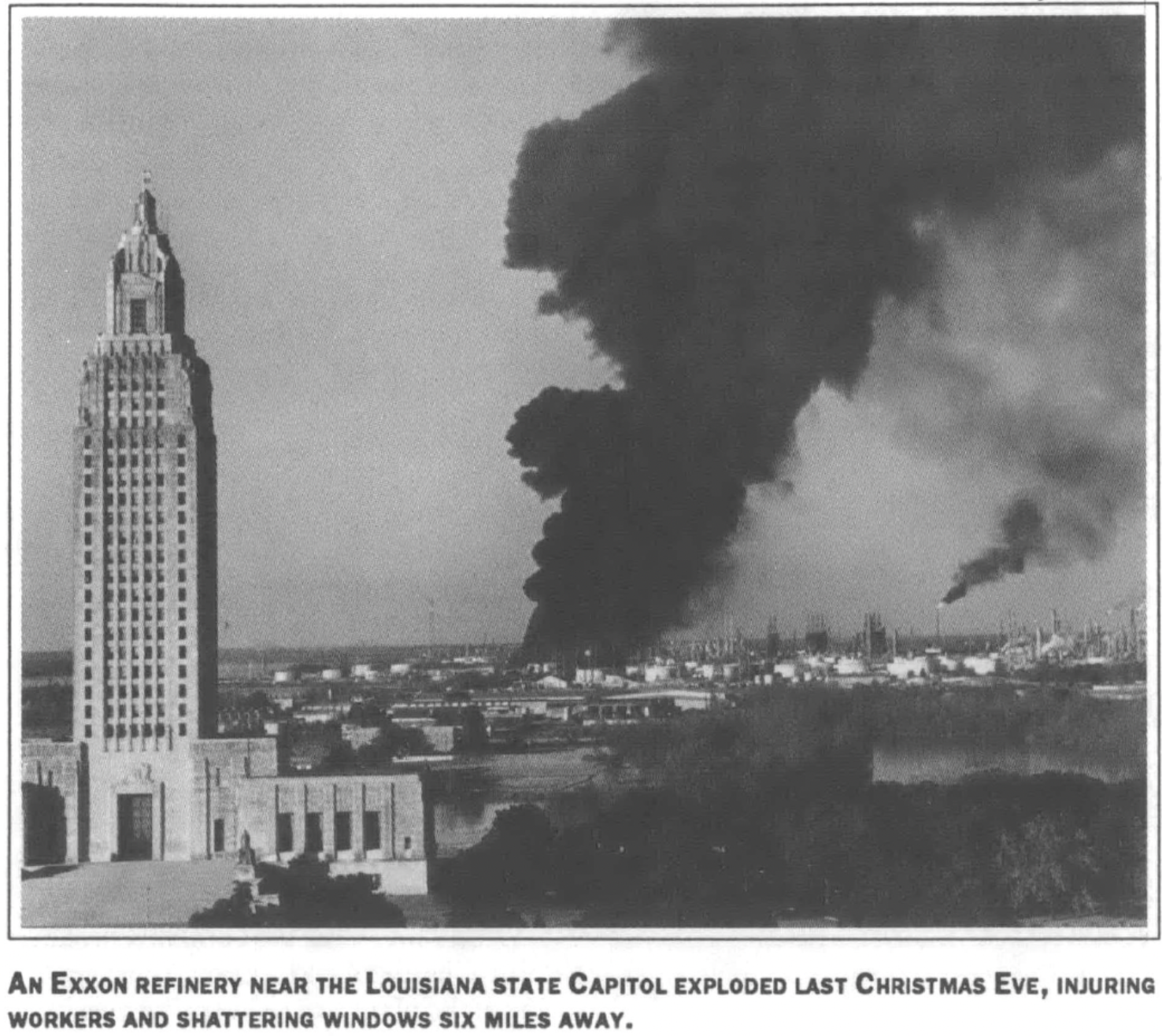

Charles Robicheaux and his family lived in another of Good Hope’s 130 homes, about 25 miles upriver from New Orleans. They had gotten so used to being evacuated because of the frequent fires and explosions at the refinery that they kept packed suitcases next to their beds. One year their Christmas dinner burned in the oven and toys were sprayed with oil during a fire and forced evacuation.

A few hundred feet from their home, towering flares turned night into day and filled the air with smoke. Toxic runoff floated in the ditches and ran into the surrounding marshland where many residents hunted and fished.

Despite the danger, Robicheaux loved Good Hope’s close-knit community, and he joined his neighbors in a bitter fight to block GHR’s expansion plans that would force everyone to leave. It was a losing battle. GHR had a habit of getting what it wanted.

Already the nation’s largest independent refinery, GHR was processing 250,000 barrels of high-sulfur crude oil worth $6 million in sales each day. It employed hundreds of workers, paid $500,000 in taxes to the parish, and plied elected officials from the courthouse to the statehouse with jobs for their families, contracts for their businesses, and generous contributions for their political campaigns.

One year, GHR violated its water pollution permit 311 times; the state finally took action when the company dumped five tons of phenol, a caustic poison, into the Mississippi River. Facing a possible $7.9 million fine, GHR’s attorney sent a letter to state officials warning, “An injudicious exercise of judgment resolving this matter by the Environmental Control Commission could fatally affect the refinery, its operations and employees.”

The state decided on a $260,000 fine. That same year, GHR boasted a $50 million profit.

Hungry for more, the company broke the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers union at the plant and relied on an everchanging lineup of transient workers whose lack of skill and stake in the surrounding communities led to more disasters. As the refinery’s daily operations wore down local resistance, GHR pressed parish officials to rezone Good Hope so the refinery could expand. The company reminded officials that an earlier decision to move its corporate headquarters to the parish was based on a “pledge to assist us in any way possible to assure the most profitable operations here.”

On a September night in 1980, 500 residents from Good Hope and nearby towns packed the council chambers. Over their protests, the council decided Good Hope was standing in the way of progress: The entire town and all its people would have to move to make way for the refinery.

Most of the residents got enough money for their homes to buy brand new houses on another street in another town. But the money didn’t make up for the loss of friendships, the loss of their way of life.

But the ultimate indignity was yet to come. Less than a year after the pain of uprooting and relocating, GHR closed its Good Hope refinery. It remains closed to this day, a rusting monument to short-term corporate and political priorities.

“It makes you feel an emptiness after all we went through for all these years,” said Charles Robicheaux. “For what? It’s just a letdown to see that all the houses are gone and the industry too.”

Robicheaux pointed to his new residence. “This is my house,” he said. “My home is in Good Hope.”

Cancer Alley

The destruction of Good Hope is not an isolated incident in Louisiana. Rather, it stands as a metaphor for the dashed hopes and devastated habitats left by the state’s economic development policies.

Perhaps the ultimate symbol of how distorted the policy has become happened four years after the Good Hope Refinery shut down: the Louisiana Board of Commerce and Industry gave GHR local property tax breaks worth $40 million — even though the company provided no jobs and even though it still owed the state $90,000 in air pollution fines. GHR made more than $1 billion from what flowed from the earth at Good Hope, but gave only a tiny part back to the residents. The Earth itself got even less respect.

The roots of this policy are deep. Since Louisiana was colonized by France, England, and Spain, its natural resources have been exploited by outsiders and compliant local officials. Northerners and Europeans, using slave and cheap black labor, grew and exported sugar cane and cotton. Then came the timber companies from the East and Midwest to strip the hardwood forests and cypress swamps. In the latest round, giant petrochemical firms have sucked 12 billion barrels of oil and 113 trillion cubic feet of natural gas from the ground, turning much of it into bulk chemicals and plastics for cars, clothes, and home conveniences.

The results of this reliance on the petrochemical industry have been devastating:

▼ According to data from the Environmental Protection Agency, Louisiana ranks first nationally in the per capita levels of toxic chemicals spewed into the air — 31 pounds per person or 138 million pounds total.

▼ Of the 25 counties with the most toxics released into the air, land and water, more are in Louisiana than any other state.

▼ Three of the six most toxic facilities in the nation are located here — American Cyanamid, Shell Oil Co. and Kaiser Aluminum.

▼ Another EPA study shows that Louisiana is home to 13 of the 32 plants where the cancer risk from breathing a single chemical is 100 times the acceptable level. The plants where the risk was estimated to be 1-in-100 or 1-in-1,000 included the big names in American industry: DuPont, Exxon, Shell, Dow, Copolymer, Union Carbide, Formose, Firestone, BASF, Vulcan, Occidental, and Crown Zellerbach.

▼ Every day, 21 Louisiana residents die of cancer and 41 new cases are diagnosed — rates well above the national average. Not surprisingly, the parishes located along the Mississippi River’s “Chemical Corridor,” where most of the plants sit, rank in the top 10 percent in lung cancer deaths in the United States, giving the region its nickname, “Cancer Alley.”

▼ Other studies show that people who work in the state’s petrochemical and paper pulp industries, or who drink from water supplies fed by the Mississippi (like New Orleans residents), all have significantly higher death rates from cancer. A state task force estimates the disease and its treatment costs Louisiana $176 million each year. The problems have gotten so bad that industry itself is feeling the bite. Ozone levels in Baton Rouge are so high that plants are forbidden to expand unless they reduce their emissions, and two new chemical plants were recently prohibited from building altogether.

With the damage so widespread, it’s fashionable these days to say that Louisiana sold its environmental soul to the petrochemical industry in exchange for jobs and prosperity. Les Ann Kirkland, president of the Alliance Against Waste and Action to Restore the Environment, disagrees.

“That’s bullshit,” Kirkland says. “They didn’t tell us what the price was. You didn’t know what was at stake until it was too late.”

“A Tragic Legacy”

The hidden cost of the lax regulation of the petrochemical industry mounts each time there’s a discovery of a contaminated drinking supply, ruined tract of wetland, or leaking storage tank. In Louisiana, those discoveries come almost daily.

About five miles from Good Hope, close to a public school, a highway construction crew recently found themselves in the middle of an abandoned oil refinery that had been closed in the ’50s. The site turned out to be loaded with high levels of asbestos, heavy metals, and toxic chemicals. Construction of another highway in north Louisiana was also stopped by an abandoned site.

In Bossier City, residents of an apartment complex smelled strange fumes in their homes. They eventually discovered that the complex was built on top of another abandoned waste site. The state has about 500 such sites. The cleanup costs are unknown.

Just east of Good Hope is Bayou Trepagnier, its bottom thick with wastes from 60 years of refining and chemical production at the Shell complex next door to GHR. Shell’s wastewater treatment plant is still allowed to discharge hundreds of pounds of toxins into the productive marshland each year. Cleanup of the bayou has not yet begun.

Throughout the state’s wetlands — the most productive renewable natural resource — are tens of thousands of oilfield waste pits, filled with chromium, benzene, and radioactive wastes. By an act of Congress, they are called “non-hazardous waste sites” and are therefore exempt from federal monitoring standards. Louisiana has more of these sites — some 200,000 — than any other state.

The Congressional reclassification of these sites in 1980 saved the petrochemical industry millions of dollars. Its chief sponsors included powerful Louisiana Senator J. Bennett Johnston. The result is what the New Orleans Times-Picayune called “a tragic legacy, an environmental nightmare of appalling dimensions” that threatens underground water supplies and estuaries that produce one-fourth of the nation’s seafood catch.

Big Breaks

Louisiana’s economic dependence on petrochemicals — and its inability to clean up the mess left by the industry — dates back to the tax policy of Huey Long, the Depression-era governor who gained national attention for his bold promises to “Share the Wealth” of corporate America. His popular program depended heavily on an increase in the severance tax on oil production to pay for new roads, school books, state hospitals, and old-age pensions.

As the oil business boomed, so did the state treasury. Even in good times, the cozy arrangement made lawmakers and regulators reluctant to bite the hand that fed them. But when the industry went bust in the early 1980s, everyone suffered.

This July, Louisiana faces a $700 million deficit. State-supported hospitals have cut back services, and have refused to deliver babies in some locations. Unemployment, which continues to top national levels, long ago depleted state reserve funds.

With basic human services cut to the bone, there’s little left for the environment. The total state budget for regulating hazardous wastes was $3 million in 1986, less than a fourth what New Jersey spends for problems caused largely by a petrochemical industry about the same size as Louisiana’s.

Louisiana’s revenue problems are compounded by the fact that its historic reliance on the severance tax was offset by massive property tax subsidies. In the midst of its current crisis, the state has continued to pursue an industrial policy that gives business and industry about $500 million a year in tax breaks. The biggest breaks go to the petrochemical industry, which is allowed to write off $200 million a year in local property taxes.

The result: The state is subsidizing the very corporations that are destroying its natural resources and sending its citizens to the hospital with cancer. Not only does state policy encourage pollution that leaves huge cleanup bills, it also grants tax breaks that make it impossible for state and local governments to pay the bills.

“The companies have given us environmental problems, and we have paid for them through these exemptions,” said Carl Crowe of the state AFL-CIO. “Environmental problems left behind by bankrupt companies are cleaned up with taxpayer dollars.”

The South as a whole has often used “tax incentives” to attract industry, and studies show that Louisiana outranks its neighbors in granting corporate concessions. Yet many studies also question whether the tax breaks actually work, citing evidence that companies simply play state against state in a bidding war to cut themselves the best deal.

“None of the overall tax requirements in any of the states varied sufficiently to change operating costs more than .2 percent,” wrote James Cobb in his study of industrial development, The Selling of the South. “Competitive tax cutting or exemptions negated the advantages any particular locale might have had in attracting new industry.”

The real reason industries came to Louisiana, Cobb found, was for its cheap oil and natural gas, its access to markets via the Mississippi River, and its cheap, unorganized labor. “One of the reasons for the South’s success is that developing nations like Germany and Japan decided to export their heavy, polluting industries,” Cobb said. “Foreign investors appreciated not only the South’s cheap labor and low taxes but also its apparent ability to absorb industries that produced large amounts of wastes and contaminants.”

Louisiana has paid dearly for these deals. A study by Oliver Houck, an environmental law professor at Tulane University, found that two-thirds of the industrial tax breaks granted in 1984 — about $14 million — went to companies that had violated environmental laws.

“We are simply underwriting pollution and significant health risks,” Houck said. “Even though the permit levels are permissive, you still have a high violation rate. Local governments are being forced to sacrifice schools so that industry can locate there and pollute them.”

According to Houck, violators are receiving tax breaks that are about 10 times greater than the potential fines they face. Placid Oil was fined $625,000 for 310 violations in 1982, but recouped several times that amount in local tax breaks.

What economic benefits do the citizens of Louisiana reap from these tax breaks to industry? The study by Houck showed that petrochemical companies receive 80 percent of all industrial tax exemptions but create only 15 percent of all permanent jobs.

A study set for release this spring by Louisiana Coalition for Tax Justice found that tax breaks often exceed the wages paid new permanent employees — and that many companies receive tax breaks for projects that create no permanent jobs. On average, the study found, local governments pay a subsidy of $100,000 for every permanent job created.

Average citizens not only foot the bill for the subsidies to industry, they also pay higher taxes to make up for the lost revenue. Louisiana officials have repeatedly raised excise and sales taxes on items like food and drugs — a tax which hits the poor the hardest.

Toxics March

The deadly state of the environment has started to anger many citizens who feel that state industrial policy is shaped less by visionary, long-term thinking than

is by the demands of the existing business power structure in Louisiana. Lax regulation and outright corruption have unleashed a backlash of citizen revolt — often spontaneous and haphazard, but sometimes effective in challenging the petrochemical industry. About 25 grassroots environmental groups have banded together under the banner of the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, uniting workers, tenants, and civil rights activists across the state.

In Geismar, where chemical giant BASF locked out 300 workers for over five years, the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers Local put the company on trial for its environmental and safety record. The union spearheaded a coalition that included community and environmental groups, broadening the attack against the German-based corporation. The campaign worked, and workers won their jobs back earlier this year.

Last year, with the help of the Sierra Club, Greenpeace, and the National Toxics Campaign, citizens organized the state’s first-ever Toxic March from the Superfund site in Baton Rouge, down the “cancer alley” of chemical firms along the Mississippi River to New Orleans.

People’s outrage began to reach elected representatives. Bills were passed mandating that toxic air emissions be cut in half, taxes on hazardous waste be increased, and municipalities recycle 25 percent of their solid wastes. Funding for the state environmental department was doubled. The regulatory realm also responded, approving tougher rules for hazardous waste injection wells and water quality standards — over the objection of the state’s most powerful oil, chemical, and business lobbyists.

But while much has changed, much remains the same. Industry sued to block the injection rules and had them temporarily suspended. The air toxics bill named no specific chemicals, leaving that to the drawn-out regulatory process. The state Commerce Board still refuses to take the environment or any other factors into account before granting millions of dollars in tax breaks. Louisiana industries continue to legally emit millions of pounds of known disease-causing chemicals into the environment.

Organizers are planning a second Toxics March to coincide with Earth Day, vowing to keep up the pressure on elected officials. The fight for a healthy environment goes on, but many citizens caught up in the struggle say they will never be the same.

Camille Weiner moved out of her home in Good Hope when the GHR refinery expanded a decade ago. Today she lives in a new town. “The neighbors are nice and everything, but it’s not like Good Hope,” she says. “It’ll never be like Good Hope.”

Tags

Zack Nauth

Zack Nauth, a former reporter for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, is director of the Louisiana Coalition for Tax Justice. (1990)