This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

New Orleans, La. — For nearly a century the gray granite monument stood on Canal Street, its 20-foot obelisk rising from the middle of the main downtown thoroughfare. Throngs of tourists and office workers bustled past it each year, but few paused to read its modest inscription commemorating the Battle of Liberty Place and the “white supremacy” that “gave us our state.”

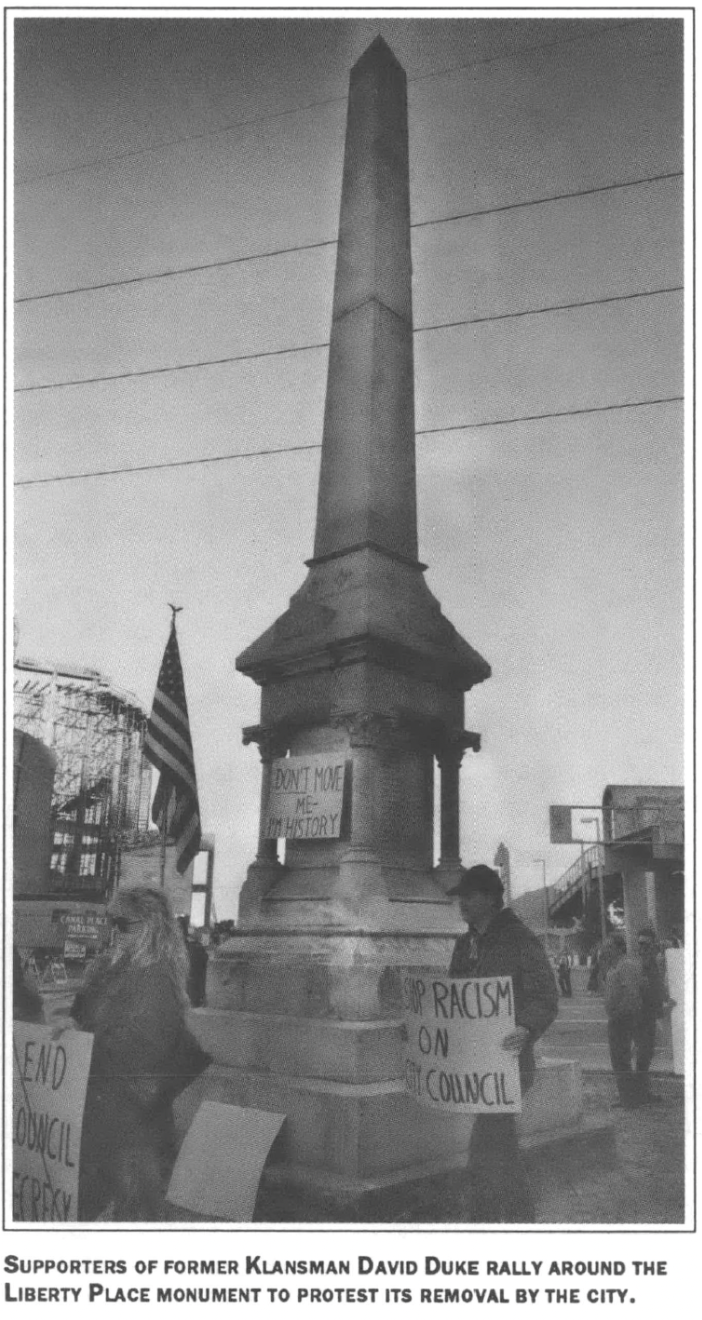

But each September 14, on the anniversary of the battle, the monument became the rallying point for white supremacists in this black-majority city. State Representative David Duke, former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, once marched around the monument shouting “white power” and “all the way with the KKK.”

Today street improvements have temporarily exiled the monument to suburban storage, but the battle over its fate is far from settled. The city reportedly plans to relocate the monument a few blocks away to ease the traffic flow along Canal Street, but the compromise has satisfied no one. The NAACP wants the monument permanently removed, while Duke and historic preservationists say they will fight to keep it near the riverfront.

Why has a simple monument sparked such a heated debate? The answer dates back to the Civil War, when white elites in New Orleans began to rewrite history to suit their political needs. Over the past century, they have fostered a mythology about the Battle of Liberty Place that has shaped social action and buttressed a climate of white supremacy that the city is still struggling to escape. The current battle over the monument involves not simply competing conceptions of the past, but conflicting visions of the present and future.

A Gentleman Mob

New Orleans doesn’t have a deep Confederate tradition. True, it sent soldiers and munitions to the Southern armies. Confederate veterans used to hold their reunions here, and a towering statue of Robert E. Lee, commanding a traffic circle in the heart of the city, was one of the first important Confederate monuments erected in the post-Civil War South.

But New Orleans, with its large immigrant population and substantial Northern-born business community, was a divided city during the war. The river-borne commerce of the Midwest tied the city’s economy firmly to the Union. Indeed, New Orleans was only in the Confederacy for 15 months. After a federal flotilla ran the downriver batteries and entered the city in May 1862, Union generals governed the city and surrounding parishes — often with the active support of local residents.

Lacking a glorious Confederate tradition to call their own, influential whites in New Orleans had to look elsewhere for a history that would justify their attempts to dominate blacks. They turned to a bloody white uprising called the Battle of Liberty Place, which took place on September 14, 1874 at the foot of Canal Street along the riverfront.

The battle grew out of a disputed state election in 1872. Democrats used fraud to win the election, and Republicans — backed by the Grant administration in Washington — used their control of the election board to win it back. The following year, Republican leaders experimented with a biracial plan called the “Unification Movement” that envisioned splitting political offices evenly between blacks and whites.

The movement failed to take hold, but it shook the city’s Southern-born and ex-Confederate element. In response, a group of upper-class Democrats who belonged to exclusive male social clubs like Pickwick and the Boston Club organized a military arm of the party known as the White League.

The goal of the White League was to unify the city’s upper classes behind a standard of violent resistance that enshrined the ideal of white supremacy. The League platform, adopted in the summer of 1874, dripped with racist rhetoric: “Having solely in view the maintenance of our hereditary civilization and Christianity menaced by a stupid Africanization, we appeal to the men of our race . . . to unite with us against that supreme danger . . . in an earnest effort to re-establish a white man’s government in the city and the State.”

According to the manifesto, the white men of Louisiana had a right to resume “that just and legitimate superiority in the administration of our State affairs to which we are entitled by superior responsibility, superior numbers, and superior intelligence.”

On September 14 the White League attempted a coup d’etat. Approximately 8,400 members led by Fred Ogden attacked state militia and police under the command of James Longstreet, a former Civil War major general under Robert E. Lee.

It wasn’t much of a battle, and its political results were dubious. There were only about 30 fatalities on both sides, two of whom were bystanders who had thronged the sidewalks and balconies to watch the 15-minute skirmish. The White League won, but federal troops restored the Republican governor a few days later. It was not until the end of federal Reconstruction in 1877 that the white elite of New Orleans finally regained political control of the city.

Nevertheless, the tradition surrounding the battle came to embody the familiar nostalgia of the “Lost Cause” myth. Upper-class whites immediately began to manipulate the memory of the battle to extol social solidarity. At a celebration marking the first anniversary of the battle, one White League leader stated proudly: “If the White League is a ‘mob,’ it is at worst a mob of gentlemen.”

A Moderate Lynching

From 1877 until 1882, the anniversary day was marked by a solemn pilgrimage to the gravesites of the White League dead. Units of the state militia retraced the route of the soldiers of ’74 and ended up near the river for a 21-gun salute. Many businesses closed early for the celebration, and crowds surged through streets festooned with banners and bunting.

Soon, though, the memory of the battle dimmed. Rich citizens did not return from their summer vacations in the North in time to attend the ceremony, and the crowds dwindled. Almost from the beginning “September Fourteenth” was a waning tradition.

It took a social crisis to revive the spirit of gentlemen mobs. In March 1891, a jury acquitted 11 Sicilians accused in the Mafia slaying of the police chief a year earlier. Several Liberty Place veterans called for a mass meeting, and on March 14 a huge crowd gathered at a statue on Canal Street.

“Not since the 14th day of September 1874 have we seen such a determined looking set of men assembled around this statue,” proclaimed one White League descendant. “Then you assembled to assert your manhood. I want to know whether or not you will assert your manhood on the 14th day of March.”

To cries of “shoot them,” the respectable crowd vindicated its virility by marching on the city jail and lynching the prisoners. City newspapers congratulated the organizers for their “marvel of moderation.”

The riots gave a much-needed boost to the “September Fourteenth Monument Association,” which had been struggling for years to raise enough money to erect a monument at Liberty Place. At the anniversary celebration that September it was finally able to lay the foundation. Now the white elite of New Orleans had a concrete symbol around which to rally.

Those Heroic Days

In the early years, those commemorating the Battle of Liberty Place kept their rhetoric of white supremacy somewhat muted, perhaps fearing federal intervention if things got out of hand. Instead, they talked about “good government” and “home rule” — by which they clearly meant the right of white men to dominate blacks without federal interference.

It wasn’t until wealthy whites succeeded in disenfranchising many black and poor white voters at a constitutional convention in 1898 that they felt safe enough to drop the pretense. “We are gathered together,” announced the convention president, a former White Leaguer, “to eliminate from the electorate the mass of corrupt and illiterate voters who during the last quarter of a century degraded our politics.”

As the actual events of the battle receded further from living memory the legend of Liberty Place took on almost mythological proportions. Reconstruction was an oppressive military dictatorship. “Negro domination” imposed by a Northern-controlled Congress bled the state financially. Finally, the poor people of New Orleans grew so horrified by the “negro heels on white necks” that they rose en masse and overthrew the despotism of an alien race and their white bosses.

Where other Southern towns and cities could celebrate Confederate battlefield valor, upper-class whites in New Orleans found it deeply satisfying to concoct a history in which their brave young men actually won the peace — and this on the ground where early in the Civil War the city fathers had been forced to surrender. The Fourteenth of September was their tradition, and they were proud of it. Fathers passed it down to children through dramatic re-tellings of those heroic days.

Hilda Phelps Hammond, a blue-blood, recalled her father’s oft-told tale of “how New Orleans boiled like a kettle under insults and indignities, of how the heroic White League was formed by those citizens who decided that life without liberty was no life at all, of the flaming posters appealing to merchants to close their stores and fight for freedom.” He always concluded by reading, in a firm voice, General Ogden’s victory statement.

But as the mythologizing became more unreal and the white supremacy more strident, the commemoration observations died down. After 1900, the ceremony consisted of a few Daughters of the Confederacy visiting the White League gravesites. The 30th anniversary services at the monument passed practically unnoticed.

By the Sword

Once again it took a perceived threat to uptown white elites to revitalize the legend of Liberty Place. This time, the threat was supplied by Huey Long, who was distributing public benefits equally to poor blacks and whites.

Upper-class citizens of New Orleans were frightened by Long and his radical programs. Sensing an eventual showdown with the Kingfish, they almost instinctively rallied around the Liberty Place Monument.

In 1932, the city added an inscription to the monument’s base, etching in granite what could only be whispered when the obelisk first went up: “United States troops took over the state government and reinstated the usurpers but the national election of November 1876 recognized white supremacy and gave us our state.”

When the showdown between Long and the conservative New Orleans machine came in 1934, it had all the characteristics of an old-fashioned Liberty Place shootout. Determined to elect his own candidates in city elections that September, Senator Long had his puppet governor declare “partial martial law” in the city and send state guardsmen to capture the voter registration office.

Mayor T. Semmes Walmsley, whose forebears had fought at Liberty Place, deputized 400 special policemen and armed them with powerful weapons, including Gatling guns. There was a wildness in the air. Hodding Carter, who was then publishing a paper in Hammond, wrote that only the use of “ancient methods” would curb Longism, and he hoped to God that “Louisiana men awake to these wrongs and to the sole remaining method of righting them.”

The 60th anniversary celebration of Liberty Place that year was invaded by the spirit of armed resistance. The keynote speech, broadcast over the radio, closed with the orator observing that the spirits of the heroes of 1874 were peering down from above “to find out if their sacrifice has not been made in vain, if we love liberty as dearly as they did.” The published version of the address boldly announced, “SO WE FINALLY FOREVER RE-ESTABLISHED WHITE SUPREMACY IN THE SOUTHERN STATES.”

The armed violence of ’74 never broke out. The city election passed with only minor scuffles at a few polling places, and the Long candidates won easily. The troops were withdrawn. The tradition of the gentleman mob, it seemed, had died completely.

But a year later Long was also dead, assassinated by a socially prominent physician with ties to New Orleans. Hilda Phelps Hammond, who had learned the White League legend at her father’s knee, exulted that “he who lives by the sword perishes by the sword.” She could have been describing the sentiments of 1874. There is no evidence that Long’ s genteel enemies in New Orleans plotted his murder. But in resuscitating a tradition that sanctioned armed violence against political opponents they certainly helped foster conditions that made his death possible.

Dixiecrats Unite

As the civil rights movement gained momentum, the Liberty Place legend gained new life. In 1948, faced with growing civil rights action across the country, arch-segregationists from the Deep South organized the States Rights party and pulled away from the Democrats.

Some of the Dixiecrats participated prominently at the Liberty Place ceremonies the following year. “It is one of history’s tragedies that we are gathered here at a time when the ideals for which the men of 1874 fought are being viciously attacked again on all fronts,” Congressman Eddie Herbert told the crowd at the monument. “The struggle for home rule must be won again.”

Defenders of segregation could draw on the legend of Liberty Place to fend off unwanted social change, knowing the myth intellectually buttressed the established racial order more effectively than the shibboleths of white supremacy. After all, they reasoned, the Liberty Place tradition might edify the 1950s concerning the ruinous effect of federal intervention, black voting, school integration, and social mixing — historical lessons that were writ in the blood of patriots.

A year after the Supreme Court issued its historic Brown v. Board of Education decision desegregating public schools, custodians of the monument helped subsidize an official history entitled The Battle of Liberty Place. Authored by former advertising executive Stuart Landry, a member of the exclusive Boston Club that helped give birth to the White League, the book was a conscious attempt to shore up the racial status quo.

“The Battle of Liberty Place was not a race riot nor a struggle between whites and Negroes,” Landry wrote, but rather a patriotic effort “to overthrow a dictatorship of sordid politicians.” By side-stepping explicit white supremacy, Landry fell back on the old New Orleans tradition of invoking a misremembered past to preserve a misguided present. In essence, it was a case of bad history being used to perpetuate bad politics.

Stevie Wonder Square

In 1879, a few years after the Liberty Place battle, the city’s only black newspaper, the Weekly Louisianian, had warned that more than half of the state regarded “this pompous military display” as an indication of deep hostility to black liberties. The driving spirit of the battle, the editors explained, was the refusal of whites to accept a government based upon black votes. “It is for this reason the 14th of September must always be a red flag shaken in our faces.”

By the 1960s, Liberty Place was still a red flag to blacks. The city was rocked by a battle to desegregate the schools, and students staged sit-ins at Canal Street lunch counters. Blacks had little tolerance for symbols of racism and white supremacy — especially those on the busiest thoroughfare in the city.

The NAACP Youth Council, which had spearheaded the picketing of Canal Street department stores in 1960, shifted its protests to the Liberty Place Monument. Several other black groups joined in the ongoing demonstrations. Things crested in 1974, when the Rivergate convention center on Canal Street hosted the 65th NAACP National Convention, which passed a resolution endorsing local black efforts to have the monument taken down.

Caught between the NAACP and white preservationists, Mayor Moon Landrieu tried to side-step the issue. Officials covered up the 1932 inscription extolling “white supremacy” and added a bronze plaque declaring that “the sentiments expressed are contrary to the philosophy and beliefs of present-day New Orleans.”

But disassociating the white supremacist language of 1932 from the white supremacist realities of 1874 was at best an act of historical amnesia. The demonstrations at Liberty Place continued. The centennial celebration in September 1974 attracted more picketers than pious pilgrims. Klan and neo-Nazi groups also started rallying around the monument.

Vandals soon tore off the marble slab covering the inscription and gouged out the mortared-in letters. Blacks and whites armed with spray paint dueled in graffiti on the monument’s base. The exasperated city parks department surrounded the monument with overgrown ligustrum bushes.

The confrontation peaked in 1981 when Dutch Morial, the city’s first black mayor, tried to remove the monument. Popular radio talk shows buzzed with irate complaints, and the white-majority city council passed an ordinance forbidding the mayor to remove the monument without council approval.

People had become so disconnected from the actual history that the most absurd ideas seemed to make sense. One letter to the editor seriously suggested relocating the monument next to the newly erected Martin Luther King statue in the heart of a black community because, like King’s struggle for racial justice, the Liberty Place battle “was fought for all those who believe in equality above a life of oppression.”

The Liberty Place controversy was no longer about the monument itself — it was about the fears of whites faced with black political power. If Liberty Place fell, some whites asked, wouldn’t Robert E. Lee Circle follow?

State Representative David Duke pushed the reasoning to its most absurd conclusions. “What about Jackson Square?” he asked, referring to the city statue of Andrew Jackson. “Do we have to take that down and change the name to Stevie Wonder Square?”

Gradually, however, the tradition was crumbling, even among the ranks of White League descendants. Betty Wisdom, whose father had pushed the myth of the monument for years, publicly urged that it be taken down.

“Nothing is ‘ apart of history’ unless it truthfully represents that history,” Wisdom said. “The White League monument does not do that.”

Today, officials once again hope to side-step the issue by re-erecting the monument within a block of its last downtown location. “We would not agree to removing the monument and putting it back up outside the battle area,” explained Leslie Tassin, director of the state Office of Cultural Development. “It would be like putting up a sign that said, ‘George Washington slept here’ when he slept two miles down the road.”

Those deciding the monument’s fate might be wise to ponder her words. The monument was originally conceived as a funeral memorial for White League General Fred Ogden, and the annual rites involved gravesite ceremonies conducted by patriotic ladies for fallen soldiers.

Tassin said more than she realized in her Washington slept-here analogy. Washington today sleeps in a cemetery — which is exactly where the Liberty Place monument belongs, perhaps next to the grave of General Ogden. May his soul, and those of his comrades, rest in peace.

Tags

Lawrence Powell

Lawrence Powell is an associate professor of history at Tulane University in New Orleans. (1990)