This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

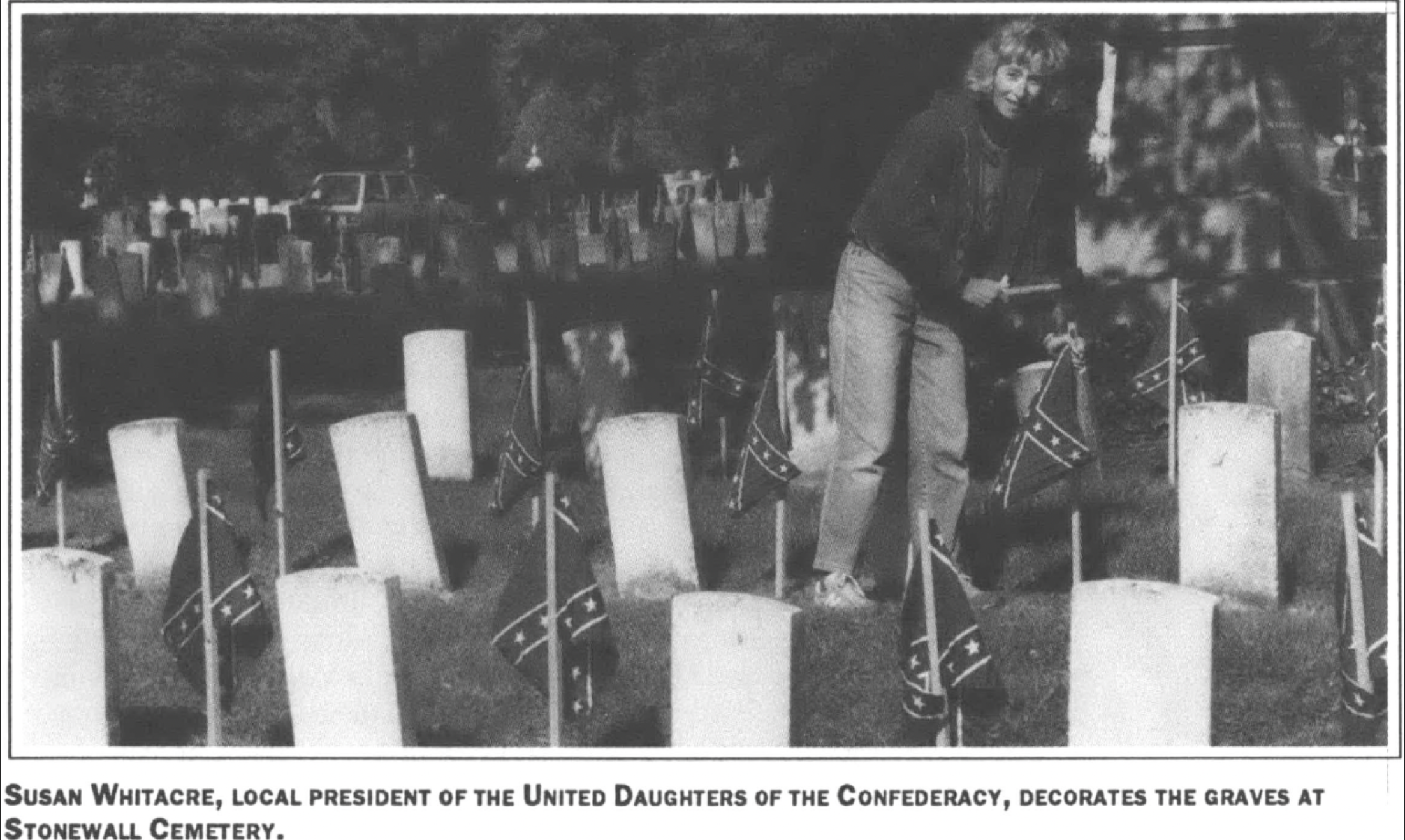

Winchester, Va. — It’s a fairly simple ceremony. A crowd assembles in Stonewall Cemetery, where each of the more than 3,000 graves has been adorned with a small Confederate battle flag. There is a prayer, a speech from a visiting dignitary, some songs from a high school choir, and a volley of gunfire from men wearing Confederate uniforms. Then there is another prayer and everyone goes home.

Confederate Memorial Day has been observed here without fail every year since 1866, but some of the older residents in town say the ceremony just isn’t the extravaganza it used to be.

Stewart Bell, a former mayor of Winchester, is old enough to have had an uncle who died in the Civil War. He has been a regular at the Sixth of June observance since 1914. To him, the 120 or so people who attend the service nowadays are “a rather pitiful little crowd.” He remembers when Confederate veterans, Masons, marching bands, and local fire companies paraded through a downtown covered in Confederate battle flags and into Stonewall Cemetery.

“In town the shops mostly closed, at least during the morning,” Bell recalls. “And the crowd gathered. Country people came in. It was a big, big day. I mean the streets were lined. It was just a day of celebration.”

Miles Around

It’s not unusual for former Confederate states to have a memorial day for Confederate soldiers, but the Sixth of June is Confederate Memorial Day only in Winchester. The rest of Virginia and most other Southern states honor their Confederate dead on the last Monday in May, the same day as the federal Memorial Day. But in Winchester, Confederate Memorial Day is June 6 — the day Brigadier General Turner Ashby died fighting for the Confederacy.

Ashby was a fierce-looking man with a long, full beard who carried himself with a martial bearing long before he joined the Confederate army. When John Brown raided Harper’s Ferry — about 30 miles from Winchester — Ashby formed a mounted unit and dashed off to defend the federal arsenal. When Virginia joined the Confederacy, Ashby and his men became part of the 7th Virginia Cavalry, and Ashby became a lieutenant colonel.

“Despite the briefness of his career as a soldier, no Southern horseman is a more picturesque character than Turner Ashby,” writes Frederick Mortin, a local historian. “Had he lived through the war, he would probably have become one of the best-known leaders of the Confederate cavalry.”

But neither Ashby nor his brother, Captain Richard Ashby, lived through the war. On October 25, 1866, their bodies were reburied in Stonewall Cemetery next to the grave of George S. Patton, grandfather of the World War II general.

The crowd that came for the reburial filled the cemetery grounds and hotels for miles around. Every year since then, the anniversary of Turner Ashby’s death in 1862 has been Confederate Memorial Day in Winchester.

“Still Valid”

“I was about 12 before I realized Memorial Day was not the Sixth of June,” says Susan Whitacre, a Winchester native. “The Sixth of June was when we put flowers on the graves of the family. We thought of Memorial Day as the Sixth of June. We forgot the other one.”

Whitacre, a pharmacist and 40-year-old mother of two, is a member of the local historical and preservation societies. She is also president of the Turner Ashby Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

She joined the Daughters, Whitacre says, because “I think history is important. I think our heritage is important. I’m proud to be a Virginian and I think a lot of the things the people fought for are still valid today. States rights was one of the important things in the war — the main reason it was fought — and I think states rights is important.”

The annual Sixth of June observance, Whitacre says, is a way of “honoring your family or your ancestors.”

Bell describes the event as “a memorial to the men and women who suffered . . . admiration of them as people.

“The central thought as I grew up was these were great people,” he says. “They had fought in defense of their country because it was invaded. I think of it as I do all this history: maintaining the identity of the community.”

Whose Identity?

But not everyone in Winchester agrees about what kind of identity the community should maintain. Blane Medley, a 19-year-old native of the area, takes issue — gently — with the talk about honoring the defenders of states rights. States rights, he believes, is “a euphemism for slavery.”

“Slavery is one of the black marks on American history,” he says. “To have to deal with that, to raise that issue again, is not always what they want to do. To talk about it is not always what they want to do. It’s not a pleasant thing to remember.”

The young man has a somewhat different perspective on the issue than Bell and Whitacre. Medley, who is black, twice performed at the Memorial Day ceremony as a member of the James Wood High School Choir.

“In some senses it was just another concert,” he says. “Looking back and thinking about the service itself, the thought came to my mind that we’re finally over that period. We remember it, but we’re not in it. Sometimes it’s good for us to look back and reflect.”

Medley believes that because the men in Stonewall Cemetery fought and died for a cause — even if it was a misguided one — they deserve respect. “I think that’s something you have to respect in anyone,” he says.

He thinks his great-grandmother, who was born a slave, would understand: “I didn’t think that my great-grandmother would roll over in her grave if I were to perform at the memorial service.”

Yankees Go Home

Bell and others who support the service say it is intended to honor those who died fighting for the Confederacy, not to preserve some notion of white supremacy.

“It’s not associated at all with ‘the Confederate flag flies again’ and all that,” he says. “It just irks me to see the Confederate flag used in that sort of significance.”

Medley agrees. The people who attend the ceremony, he believes, are “Civil War buffs” or people who have family buried among the Confederates.

“You don’t find a lot of Civil War advocates,” Medley says. “Those kinds of people don’t show up at these ceremonies. They’re not interested in it.”

If the bitter resentment left over from the Civil War seems somewhat muted in Winchester, it may be because the memories of the war and its meaning have faded with the passing generations. Bell tells of a conversation that took place between his wife and a friend of his son years ago. As they drove down the lane that separates Stonewall Cemetery from Winchester’s National Cemetery, Mrs. Bell tried, as parents will, to turn the drive into an educational experience.

She explained that Winchester was the site of several major Civil War battles and that many Confederate soldiers were buried in Stonewall, and many Yankees were buried across the lane.

“I hate the Yankees,” one of her young passengers said.

Mrs. Bell told the boys that no one should hate Yankees. The war was over a long time ago, she explained, and the North and South have long been reunited into a single nation.

“I hate the Yankees,” the boy repeated. “I like the Red Sox.”

Tags

Tim Thornton

Tim Thornton is an editor at the Winchester Star. (1990)