This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 4, "Facing the '90s." Find more from that issue here.

When Larry McAfee asked a superior court in Atlanta to help him die last September, many people supported his death wish.

McAfee, a 33-year-old who has used a respirator to breathe since he was paralyzed from the neck down by a motorcycle accident in 1985, asked the court to allow him to receive a legally-administered heavy sedative and then shut off his respirator which would lead to his death within minutes.

The state of Georgia, the Georgia Medical Association, and the Catholic Archdiocese of Atlanta all told the court that it would not be suicide for McAfee to end his life, but merely a refusal of medical treatment. The judge ruled in McAfee’s “favor,” stating that McAfee’s decision to die demonstrated a rational concern for the medical costs he is incurring.

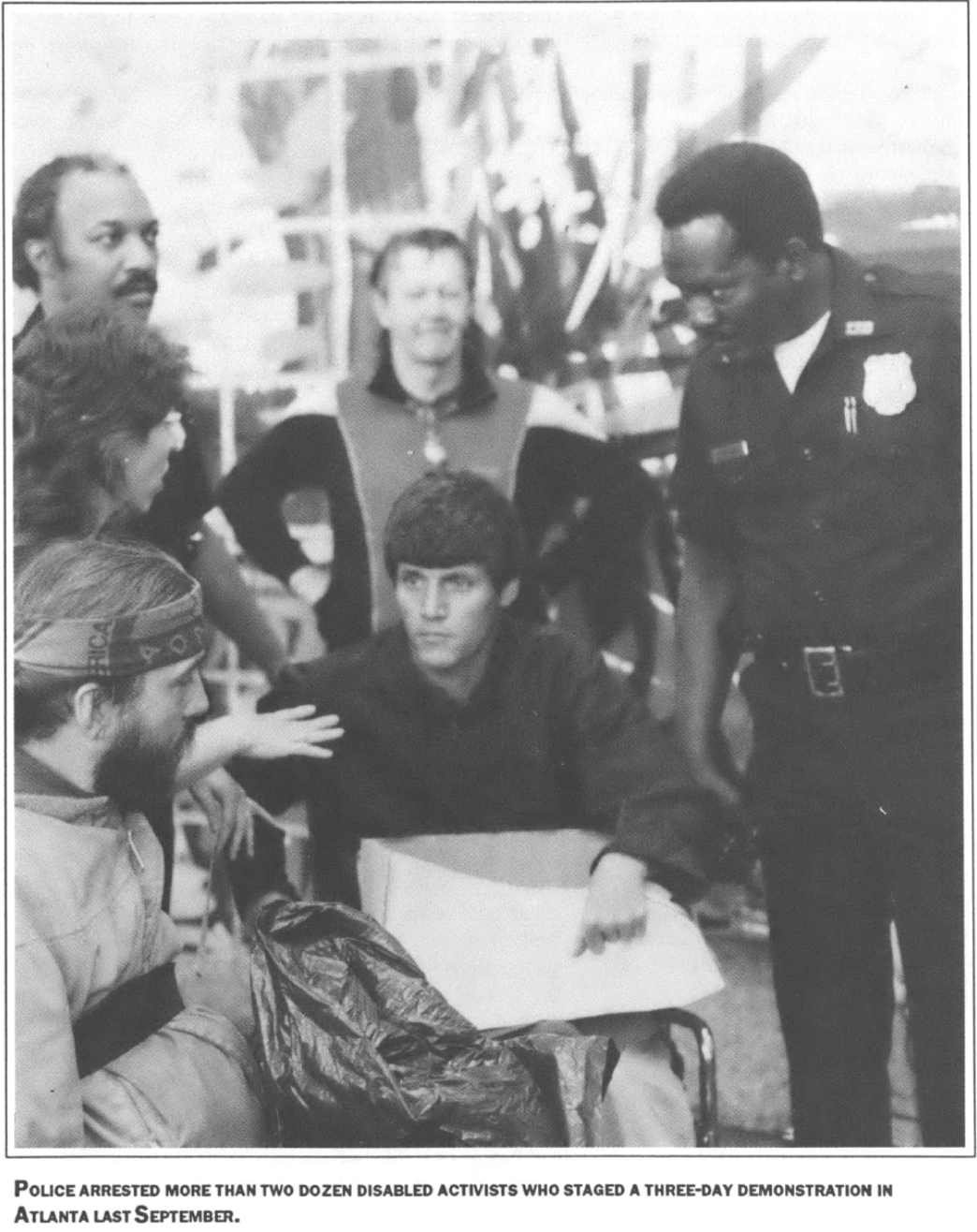

Disability activists were outraged by the decision. They pointed out that McAfee is not ill (let alone fatally ill), and could have 40 years of full and productive life ahead of him. They pointed out that McAfee has been forced to reside in an Alabama nursing home, far from his friends and relatives, because the state of Georgia refuses to fund personal assistance services for severely disabled people and because Georgia nursing homes generally refuse to admit people who use respirators.

Above all, they wondered why the state condemns disabled people to a poor quality of life by ignoring their need for life-fulfilling assistance, and then steps in and says they should be assisted to die because their quality of life is so poor.

Fearing for their lives, people with physical disabilities are calling for a deeper level of dialogue about what has been called the “right to death.” Slowly but surely, they are reframing the debate over disability by asking a simple question:

What is it that makes it so difficult to be disabled in this society that warrants death?

Earning Power

Society demonstrates in many ways that it wants people with severe medical conditions at the very least out of sight, and preferably dead. (“I want to die before I become a burden.”) Although evidence of outright discrimination abounds, disability is not commonly thought of as “oppression.”

Even people who recognize sexism and racism as oppression persist in thinking that the powerlessness of disabled people is somehow intrinsic to their medical condition — a personal, individual misfortune.

To begin to see disability as a human-made oppression — rather than an unfortunate stroke of fate — we must ask ourselves if life is being made considerably more difficult for people with severe medical conditions than it needs to be.

The answer is “Yes.”

First and foremost, disabled people are systematically kept from earning money by arbitrary rules — rules made by non-disabled society. Because most disabled people are slowed down by their physical conditions, they often lack the energy needed to accomplish the full-tilt, 40-hour week that our economic system generally demands.

Most disabled people could work at least part-time; but most employment has been set up to discourage part-time work. Many jobs are simply designed as full-time positions, and management is reluctant to change the existing arrangement. The part-time jobs that do exist usually offer lower hourly pay and entail a loss of crucial benefits, such as insurance and sick leave.

To make matters worse, our society literally builds physical barriers into the environment that cause disabled people to need more help than is intrinsically necessary, forcing them to waste enormous amounts of time and physical and emotional energy. Disabled people are routinely denied personal assistance, access to communication, basic public transportation, and even access to buildings. Existing technology that could help them overcome such barriers — things like captions on television, computer-generated Braille print and voice output — are usually unavailable.

The extra help some people need — because of inabilities intrinsic to their specific disability — is far less than we have been led to assume. Even so, such help is not available to these people in forms which allow them to retain their power and dignity as respected human beings.

This help could — and should — be available from state-paid helpers, hired and dismissed by the disabled person. Because such helpers would be public employees instead of volunteers, the disabled person would not have to cajole or reward them with gratitude, sex, or entertainment. At present, state-paid help is very hard to come by; only very severely disabled people have hope of getting it, and then only in certain states. The money to make this happen could be freed up through a redistribution of resources; the economic and human resources to make it possible already exist.

Industrial, capitalistic economies like ours fragment society into individual families — often units of only one person. Those people with disabling conditions find themselves cut off from the network of supportive friends, neighbors, and relatives who are available in an extended community. In the United States today, disabled people are generally forced to rely on one or two friends or relatives for support. At best, such a heavy responsibility leads to chronically strained relationships. At worst, it leads to the selective abortion of disabled fetuses, the denial of medical treatment to disabled newborns, and the physical abuse of disabled children and adults.

At the same time our society prevents disabled people from helping themselves economically and physically, it promotes the attitude that to need major help is shameful. Competition is idealized; cooperation, though given lip service, is viewed with condescension and suspicion. In such an atmosphere, to need long-term or very intimate help — or to encounter someone who does — causes extreme psychological discomfort. Such an attitude toward giving and receiving help is considered normal, when in reality it is nothing more than cultural convention.

From Pity to Envy

Once we realize that our society actively creates and perpetuates disablement for some citizens, the next question we must ask is: What might our economic system have to gain from such an arrangement?

Disability presents a unique problem to the economic system of capitalism. Most people can be exploited as workers, by their race, gender, or class. Even non-disabled children are future workers. But many people with severe disabilities cannot — and never will be able, no matter what the accommodation — to produce at the pace and in the form required by an economic system geared to generate large profits and privilege for a few. Far from producing a competitive amount of work, many disabled people require work on the part of other people merely to stay alive.

Because our economic system depends on workers who are used, over-tired, and under-rewarded, those who don’t work (unless they are super-rich) must be made to live visibly unenviable lives. People who cannot work “competitively” — full-tilt — must be kept impoverished, isolated, powerless, their lives miserable enough to ensure they are pitied rather than envied by unhappy, able-bodied working people.

What would happen if disabled people could move about easily on public transportation, get in and out of buildings with ease, hire state-paid helpers to assist them, work part-time with plenty of rest breaks, and receive public assistance to compensate for the limited earning power brought on by their loss of endurance? If they could contribute to community life, have friends, and be considered sexy?

If disabled people were allowed to live full and productive lives, no one would pity them or feel guilty in their presence. Instead, the degree to which able-bodied workers were oppressed would be the degree to which they envied and resented, rather than pitied and feared, disabled people. Overwork, speeded-up work, unrewarded work, lack of control over how we spend our workday — all these things would cease to be preferable to the alternative of having a “disability.” In short, exploited, able-bodied workers would be motivated to shoot themselves in the foot.

If disabled people could live their lives to the fullest, it would be clear that what constitutes a “disabling” condition depends almost entirely upon circumstance. A quadriplegic with enough money, helpers, equipment such as vans and lifts, and a group of supportive friends and lovers is not very disabled. On the other hand, an “able-bodied” worker who sprains her ankle but lacks the paid sick leave to stay at home and heal — and the helpers to do chores that have now become exhausting — is fairly “disabled.”

It is not medical condition, but economic discrimination, physical barriers, and inculcated cultural attitudes that separate people into two camps of “healthy” and “disabled.” The first must perform unfairly hard and meaningless work without question or hope for change; the second must be kept powerless, a source of pity and fear.

Anger and Hope

As disability activists across the country demand life-giving assistance, the myth that “nothing can be done” about disability is on the verge of giving way. The growing number of people who recognize “disability” as a human-made construct, a manipulation on the part of an economic system, is a basis for new hope.

But it’s a profound threat, too. After all, the fitting response to our new understanding is a deep, strong anger — not at God, the cosmos, or self, but at our physical and social environment and the people who perpetuate it.

Yet people who are disabled can afford to express anger even less than other oppressed groups. Their lack of power makes them dependent from moment to moment for their most basic needs: getting food from the refrigerator and into their mouths, going to the bathroom, having access to essential information. To express anger toward someone you are going to need in 10 minutes to help you use the bathroom is emotionally and physically dangerous.

The stakes are very high. A person repeatedly prevented from expressing anger learns over time to stop feeling the anger — or any strong emotion. Unless we confront the issue of disability honestly, the views which perpetuate the oppression take up firm residence in our own heads, completing the task.

To fight against the prevailing view of disability involves very real dangers to people with disabilities. And for non-disabled people it requires a new and very different way of seeing, thinking, feeling, and acting about disability.

But it is ultimately to everyone’s advantage to build an environment in which our economy, our physical surroundings, our technology, and even the vocabulary for giving, receiving, and negotiating major help take all citizens into account. In such an environment, people with chronic medical conditions can be happy and powerful — and no one need prefer death to illness, accident, or aging.

Tags

Eleanor Smith

Eleanor Smith is a disability activist in Atlanta, Georgia. (1989)