This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 4, "Facing the '90s." Find more from that issue here.

Lexington, N.C. — In 1936, photographer H. Lee Waters needed to try something new. Business was slow at his portrait studio, as it was throughout America during the Depression. He and his wife Mabel had been running the studio for 10 years, and to keep it going they made portraits smaller and lowered the price. They conserved film by making as many as nine individual exposures on a 5” by 7” sheet. Contact prints of these negatives, cut and sold individually, were about twice the size of a postage stamp. At 10 cents each they sold reasonably well, but it wasn’t enough. Waters needed a big idea.

Finally, he found what he was looking for. Waters switched to a different medium, and for the next six years he made more portraits than he had ever dreamed possible. He reached more customers than ever before and satisfied them more completely. The images he created were larger now, larger than life. Waters became a filmmaker.

Traveling from town to town in four Southern states, Waters filmed the public life of each community — busy sidewalks of the downtown shopping district, school groups, factory workers on break or at shift change, parades, picnics, sports events, tricks and stunts. Since no theaters had 16mm equipment, he returned to each town two weeks after he filmed, carrying his own projector to give a half-hour show at the downtown movie theater. He called his films Movies of Local People.

The silent films ran as an added attraction before the regular feature, and Waters received a percentage of the box office receipts. Tickets were a dime or a quarter, but in a typical two-day run thousands of local residents would come to see themselves, their family and friends on the big screen.

“It started out as a hobby for me, but I soon saw that it could be a good business, too,” explains Waters, a lively but mild-mannered octogenarian who still runs his studio on Main Street in Lexington and enjoys talking about his days as The Cameraman. “Everybody went to the movies during the Depression.”

From July 1936 to July 1942, Waters traveled to 118 towns and gave more than 250 shows of Movies of Local People. His subject was the audience and his audience was the subject. He attended every show and judged from the audience’s response what people liked and didn’t like, and then adjusted his filmmaking style accordingly.

The result was a fascinating body of work unlike anything else ever filmed. These are not the boring, Chamber of Commerce “Your Town” movies of the 1950s, filled with static shots of the mayor, chief of police, and other city officials at their desks. Instead, these films offer a candid view of the small-town South, democratic and lively. Waters was on the street, filming people at work and at play. Blacks are seen as frequently as whites, and in a few towns where Waters contracted with black-owned theaters, only black citizens appear in the film.

Camera! Action!

Waters shot with a Kodak Cine Special, and often kept up a rapid in-camera editing pace to get as many local residents as possible into his movies. Babies and youngsters are prominently featured, and there are advertisements for hardware stores, dry cleaners, beauty shops, bottling plants, car dealerships, cafes, and many other busi-

nesses. There are also trick shots for comic relief: fast motion shots of Main Street, the cars flying by at 150 miles an hour, reverse-motion shots of swimmers jumping out of the pool and up to the diving board; split screens of the church steeple sinking into the building below. The main draw, however, was always to “see yourself as others see you.”

The Eastman Kodak Company had introduced the 16mm format in 1923 as a do-it-yourself version of “real movies,” but only the wealthy or photographically proficient had taken up the practice of amateur filmmaking. The popular explosion of home movie making did not occur until after World War II, with the baby boom. At the time Waters was filming, most people had never seen themselves on the movie screen. “See Yourself at the Movies” was a very popular idea. Theater managers usually invited Waters to return, and in some communities he made as many as six different visits, shooting new footage for each engagement.

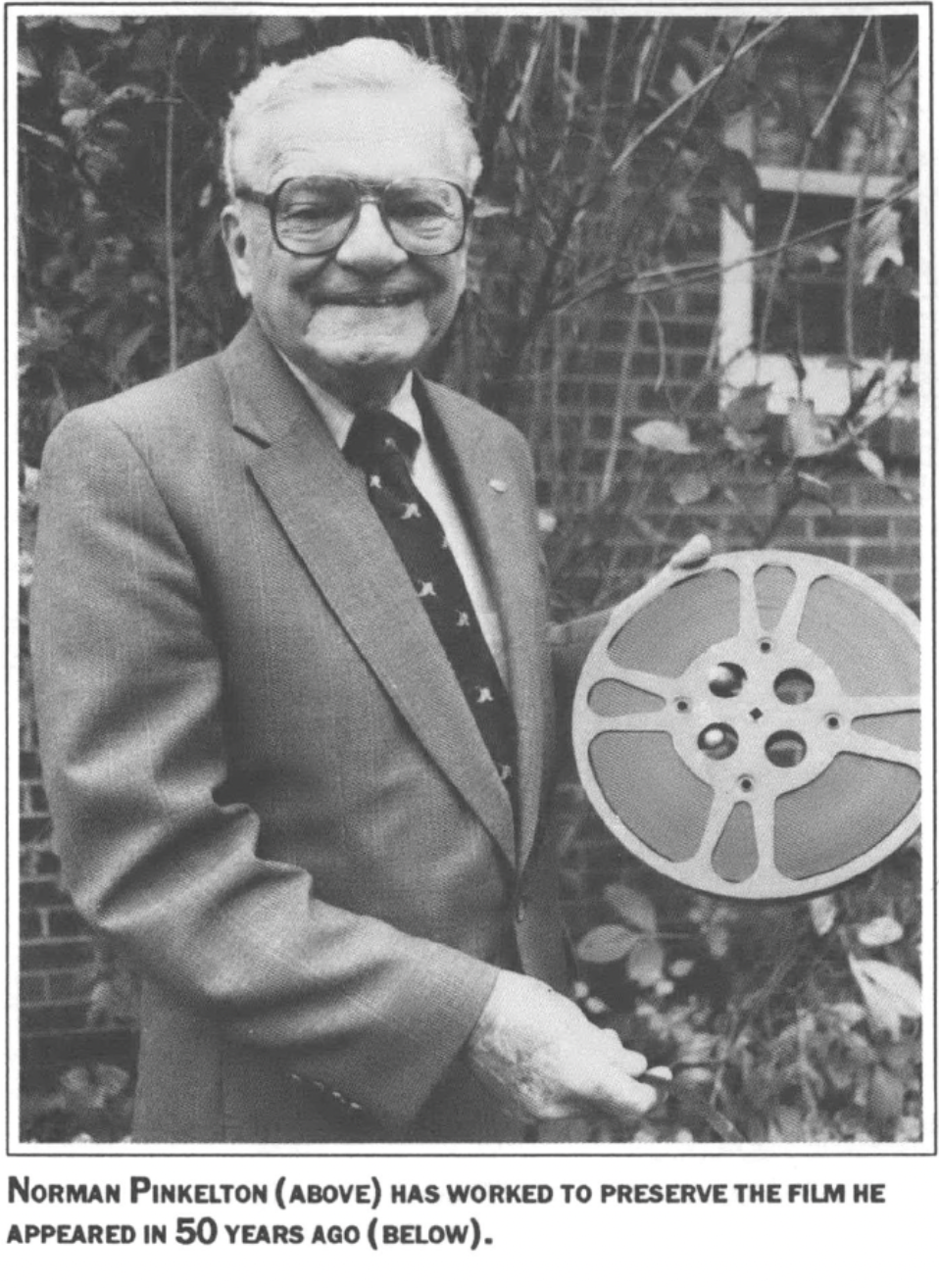

When Waters visited Greensboro, North Carolina in July 1939, one person he captured, in two brief shots, was Norman Pinkelton of the White Oak mill village. For Pinkelton, those brief moments on film continue to be a source of great joy.

“I was personnel manager for Cone Mills in 1973 and this fellow came by and said he had an old film of the mill villages, would we like to buy it? I looked at it and said, ‘Oh my, yes.’ I worked at Cone Mills for 49 years, and so many people from the White Oak, Proximity, and Revolution villages are in this movie. The first time I saw it I said, ‘Oh lordy, there I am with my son. Wait a minute, I wasn’t even married in 1939 — that’s my little brother!’”

Pinkelton, now retired, serves as the unofficial historian for Cone Mills. He is an affable, talkative man. Over the past 16 years he has shown the Greensboro Movies of Local People 85 times to more than 3,000 people.

“I don’t think public interest in this will ever slow down,” he says. “I’ve done shows for the Cone Post American Legion, Fairview Senior Citizens Club, Proximity Community Club, Kiwanis, Lions, 17th Street Residents Reunion, the Historical Guild, Proximity Methodist Church — the list just goes on and on.”

Preserving the Past

Thousands of people throughout the region share Norman Pinkelton’s strong emotional ties to the films of H. Lee Waters. There is an air of excitement when the movies are screened, a sense of engagement usually lacking in the passive viewing of mass-produced motion pictures.

“I never get tired of showing this film,” Pinkelton explains. “Nearly every time I show it, someone will say, ‘Wait— can you back it up? I think I saw my brother’ or something like that, you see, and I’ll learn a new face. I can’t show it unless I can talk.”

As he watched the film on videotape in his living room recently, Pinkelton kept up a steady stream of names: “There’s Sunshine Wyrick, he was a policeman on the Square. He was there for 40 years and it was said that he never made an arrest. There’s a Delancey boy, his brother used to play big league baseball. There’s Charles Tippett, and Mrs. Macfarlane . . . Howard Tucker, he worked in the company store. . . . Charlie McCann, Herman Simmons, Easley Byers, Elmer Walters, Mrs. Witt, Julius McDaniel, Watson Tucker, Sam Trogdon, Grover Wall, Cleo Honeycutt, Bertha Hardy, Blanche Roberts. . . .

Like many people who have seen their hometown portrayed in Movies for Local People, Pinkelton is fascinated by the depiction of life as it was 50 years ago, and the changes that have since taken place. Fortunately, many of the films are still in good condition. Waters kept the originals in his garage in Lexington rather than leaving them in theaters after the first shows.

“Back in 1936 to 1942, I wasn’t exactly sure what I was going to do with them,” Waters recalls. “They all sat in my garage for quite a while. But I figured, somehow, it might be my old age insurance.”

It was. By the 1960s, the films were already of notable historical value, and Waters began a series of “return engagements” in many communities. When individuals, public libraries, and civic clubs expressed interest in the films, he began selling the originals. Because he never made duplicates, many of the films are scattered across the region.

A full-scale restoration of Movies of Local People is currently under way at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. The search continues for many of the films. Negatives are being made from the 16mm originals that have been located, and these archival masters should be good for 100 years or more. Video transfers made from the negatives ensure that the films will remain available in the communities and a central collection at Duke.

As copies are made, the films are being shown once more in towns in North and South Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee. To older viewers, the movies provide a vivid reminder of what life was like in Southern communities during the Depression. To younger viewers, they offer a glimpse of the world in which their parents and grandparents grew up. Audiences at the screenings delight in watching the people Waters filmed react to a camera for the first time, seeing in their faces signs of the growing recognition of the camera as a powerful tool in society.

Forced by necessity to come up with a good business idea, H. Lee Waters created a priceless cultural artifact, a silent body of oral history. Many changes have taken place in the region since thousands saw themselves on the screen for the first time. Another few decades will see the passing of that generation. Used today as a meeting place for different ages, perhaps the Waters films can help us to better understand our own world.

They are certainly more helpful than Hollywood films of the same era. Ordinary citizens like Norman Pinkelton can truly teach us something about that kinder, gentler nation we’ve heard so much about lately. Every summer he tells his friends, “Don’t buy tomatoes at the supermarket — just come by my garden and pick what you need.” Last summer Pinkelton’s garden had no less than 250 tomato plants. Homegrown is best — be it tomatoes or movies.

Tags

Tom Whiteside

The Lost Colony Film is available through the State Film Library at all public libraries in North Carolina. Tom Whiteside is assistant director of film and video at Duke University and editor of the upcoming media arts newsletter Workprint. (1992)