Power in the Delta

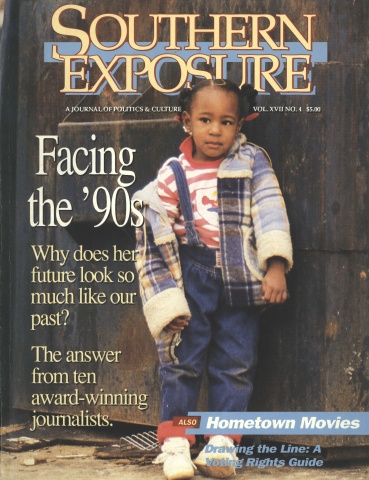

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 4, "Facing the '90s." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Little Rock, Ark. — State Senator Paul Benham Jr. took the stand on the twelfth day of the trial. Testifying under oath in federal court, not far from his office in the capitol building, Benham admitted he had referred to the Reverend Jesse Jackson as a “coon” during the 1988 presidential campaign.

“People say the Democratic Party now truly has a chance to become democratic,” Benham told a fellow legislator. “You can either vote for Dukakis or du coon.”

Benham, who is white, testified that he had merely repeated a comment he heard at the state capitol — and that he had not meant it as a joke.

Although a majority of Benham’s constituents are black, the lines of his Senate district have been drawn in such a way so that blacks account for just under half of all eligible voters. And that, say the plaintiffs in the trial, is exactly the problem.

Benham was testifying in Jeffers v. Clinton, a voting rights case brought by 17 black citizens who say the state of Arkansas intentionally split black communities into multiple legislative districts in 1981 to dilute their voting strength and chances of getting elected to the legislature. Although blacks make up more than 16 percent of the state population, they hold a voting-age majority in only four of 135 legislative districts.

The three-week trial in October exemplified the way citizens across the South have used the Voting Rights Act to fight for legislative districts that give everyone’s vote equal weight. The plaintiffs hope to create 16 black-majority districts, triggering a dramatic shift in the balance of power in the state legislature.

In the process, the case has exposed the deep racial and economic divisions in Arkansas politics — and the plantation-era attitudes of wealthy white legislators who represent some of the poorest counties in the nation.

“Bad Faith”

Senator Benham’s district is part of the impoverished Delta region, more than 200 counties that run along the Mississippi River from western Kentucky to the tip of Louisiana. Arkansas’ black population has been concentrated in the Delta lowlands since plantation days. About 40 percent of the people in the area live below the poverty level, and unemployment is more than twice the national average.

Traveling along the river, which forms the state’s eastern boundary, it is hard to believe the area is not incredibly prosperous. The river abuts acre after acre of rich black soil that has produced magnificent soybean, cotton, and rice crops for more than a century.

Yet most residents see little of the cash those crops produce. According to Wilbur Hawkins, executive director of the Lower Mississippi Delta Development Commission, the economy of the area remains “colonial.” Farm profits go to wealthy white landowners — often the descendants of slaveholders — who invest most of the money outside Arkansas while demanding that state representatives keep taxes low, thereby condemning local schools to poverty.

State legislators like Senator Benham play a key role in maintaining the gap between rich and poor. His support of wealthy landowners has won Benham a reputation as what one local newspaper called “a champion of the old power structure — white, prosperous, from an old family, and conservative.” The paper noted that Benham once hung a cartoon on his office wall depicting a smiling black man on the porch of a large Southern mansion. The caption read: “Now that’s what me and Martin Luther had in mind.” Benham belongs to an all-white country club, veterans group, and Masonic Lodge.

At the voting rights trial, Benham denied that blacks in his district live in shacks. Although he did not know how many of his constituents live in substandard housing, Benham said that “some of them choose to live that way.” He attributed high unemployment in his district to the fact that “a lot of people down there would like to work” but would lose their welfare benefits if they took jobs. Benham later admitted that there is not work available to his constituents on welfare and that the jobless rate in his district is around 17 percent — more than 10 points above the national average.

Black candidates opposing Benham have met outright discrimination. When Roy Lewellen Jr., a black lawyer, tried to unseat Benham in 1985, he was charged with a felony. The charges were instigated by the county sheriff, a friend of Benham’s. Lewellen testified he was told the charges would be dropped if he withdrew from the Senate race or surrendered his law license.

The intimidation worked. “It took me out of the last two weeks of the campaign,” Lewellen said. He also testified that prisoners in the local jail were forced to put up posters for Benham’s campaign. After Benham won reelection, a federal judge dismissed the charges against Lewellen, saying they had been brought in “bad faith.”

Getting the Chance

Such barriers to fair elections are commonplace in Arkansas. In county after county, white legislators are chosen with little black support — and the way district lines are drawn keeps it that way. Black voters hope that by redrawing those lines, they will be able to reshape the way laws are made and tax dollars are spent.

“Politics is the key to everything,” said Jerry Jewell, the only black member of the Arkansas State Senate. “We have education, but the political system is closed. That affects everything else.”

Jewell hopes that by opening up the political process, the voting rights case will also increase economic power for blacks. “The state economy is controlled by 5 to 10 people,” he said. “Blacks need economic power. . . . Give blacks money and hold them accountable, and they will produce.”

Jewell believes that a voting rights victory will also send a signal to blacks that their votes count. “It is not simply monetary oppression, but an attitude of hopelessness. Blacks need to feel they have a voice, and that they have a chance.”

Getting that chance is what the court case and its legal touchstone, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, are all about. Passed at the height of the civil rights movement, the law gave citizens the right to sue state and local governments for intentionally discriminating against minority voters.

In 1982, when Congress renewed the act, it also outlawed all unintentional voting discrimination, making it easier for blacks to challenge unfair election systems throughout the South. In Arkansas, voters are challenging the way the state drew up legislative districts in 1981, splitting black communities into larger white districts. As a result, the suit contends, only one black senator and five black representatives have been able to win election to the Arkansas legislature.

In the Delta, the 1981 apportionment plan created 10 election districts for the state House. Black voters were divided up and spread throughout the districts. Although the black population in each district is substantial, it falls just short of a majority. Black voters make up between 40 and 49 percent of five districts, and between 30 and 39 percent of four districts.

Ben McGee is the only black state representative from the Delta — and he was elected only after a voting rights challenge forced the state to create a black-majority district in the Delta in 1988.

The current case asks the court to redraw legislative districts to include three Senate districts and 13 House districts with black majorities. Jerry Wilson, a demographer for the non-profit Southern Regional Council of Atlanta, testified that those black-majority districts could be created based on existing black communities, without splitting them into multiple districts as the state did in 1981.

Not-So-Secret Ballots

Redistricting is crucial for blacks in Arkansas, because voting occurs strictly along racial lines. In legislative races held in white-majority districts during the last decade, whites have voted as a group to defeat every black candidate who ran against a white candidate.

At the trial, former Arkansas Governor Frank White insisted that “it is possible that a minority can be elected where they don’t have a majority in a district.” He admitted, however, that no white majority in Arkansas has ever elected a black candidate.

When asked to give an example of a white majority supporting a minority candidate, White cited “the race for the mayor of New York City.” Under questioning, he admitted that the legislative districts he helped draw up in 1981 have “diluted black voting strength.”

Other testimony at the trial revealed a dramatic history of racial discrimination in Arkansas politics. Ben McGee, the described how voting fraud has prevailed in Crittendon County for over 20 years.

“It’s unbelievable how the numbers turn out,” McGee said, citing the 1984 city council race in the town of Earle. When the counting of absentee ballots was suspended at midnight, black candidates were ahead. When the winners were announced the next morning, McGee testified, “All the blacks had lost.”

Lonnie Middlebrook, a black city council member in Blytheville, said blacks

are often intimidated at polling places by white election judges and clerks. Many are “of the opinion their vote is not really a secret ballot — and that is a form of intimidation.”

Middlebrook and others said election officials often use scare tactics, and polling places frequented by black voters are set up in inconvenient areas or simply relocated without any notice.

Discrimination also occurs outside the voting booth. In 1982, Leo Chitman became the first black mayor of West Memphis after winning his race with a plurality of the vote. A few months later, white lawmakers passed what became known as the “Chitman Bill” requiring runoff elections in local races where no candidate attains a majority. The new law had one effect: It made it much harder for minority candidates to win election.

Evidence presented at the trial included numerous examples of racial appeals used against black politicians. The Arkansas Gazette ran a news story headlined, “Racial Lines Drawn in Pine Bluff Mayor’s Race,” when a black candidate first advanced to the runoff for mayor of that city. The story quoted a white citizen saying, “The black people of Pine Bluff have a good opportunity to elect a black mayor. If the [white] people don’t turn out and vote, we’ll have a black mayor.” The black candidate lost in a record turnout.

When Carroll Willis Jr. ran for judge in Desha County, his white opponent stood on the steps of the courthouse and proclaimed, “We don’t need no nigger judges. . . . I twill drive whites out of town.”

Because racial appeals are so widespread, black politicians have learned to keep their skin color a secret. Roy Lewellen testified that when he ran against state Senator Benham, he “concealed” his race by “keeping my picture out of campaign brochures.”

Sidewalks and Ditches

As witness after witness took the stand in the voting rights trial, a sobering picture emerged of blacks trapped in a vicious cycle: Poverty and inferior education keep many away from the polls — and the lack of power at the polls condemns many to inferior education and poverty.

In Lee County, for example, the average per capita income for blacks is $1,923 a year, compared to $5,353 for whites. In Chicot County, 43.7 percent of blacks have no car, compared to 7.3 percent of whites. In Desha County, 32.3 percent of blacks have no telephone, compared to 8.9 percent of whites.

“We live separately. We vote separately. We die separately and are buried separately,” said R.C. Henry, a black justice of the peace from the Delta. “White neighborhoods have curbs, sidewalks, and adequate drainage. Black neighborhoods have ditches.”

Linda Whitfield, a Helena County resident, agreed. “Black poverty is not the same as white poverty,” she said. “It is a totally different situation.”

Evangeline Brown, an 80-year-old retired teacher from Chicot County and one of the lawsuit’s 17 plaintiffs, said schools in her area are so segregated that they even have “separate proms for black and white students.” Such discrimination, she testified, produces voters who do not know how to take part in the political process.

Wealthy Friends

White representatives seem content with the segregation and poverty that keep them in power. “What have they ever done for economic development here?” asked Roy Lewellen. “I can’t point to anything. It’s only rhetoric.”

Ben McGee, the state representative from the Delta, said many white legislators voted against a tax reform bill he sponsored that would have exempted 64,000 poor residents from paying taxes. The reason? “It would cost approximately $700 more in taxes to their wealthy friends,” McGee testified, “and they didn’t want to pass this burden on to them.”

Nancy Balton, a white representative from Mississippi County, said she voted against the tax bill because “the middle-class people asked me to.” Reminded that the tax bill did not affect the middle class and only proposed raising the taxes of those with incomes of over $100,000, she said middle-class people are tired of seeing those on welfare living better than they do.

Balton admitted that only a handful of people in her county have incomes of over $100,000 — and that her own income has, at times, exceeded $100,000.

According to the most recent census figures, Mississippi County does not have much of a middle class. Per capita income is $5,685 for whites and $2,426 for blacks. Forty-five percent of black families and 13.4 percent of white families live in poverty. Despite her vote against the tax reform bill, Balton testified that she “bled” when she saw extreme poverty while campaigning in black neighborhoods.

Judge George Howard, the only black member of the federal bench in Arkansas, asked Balton how many black people she had chosen as legislative pages.

“Unfortunately, none,” she replied, explaining that she usually selected pages from those who asked to be chosen.

“Given the situation over the years,” Judge Howard replied, “perhaps you should have taken the initiative.”

In later testimony, Balton bristled when her family farm was referred to as a “cotton plantation.” She admitted, however, that her farm holdings are extensive and that her farm employs blacks as manual laborers and whites as managers. Balton also admitted that she belongs to an all-white country club.

Robert White, from Ouachita County, testified that white representatives provide their black constituents with a “superficial type of representation” by “showing up for anniversary celebrations in churches or appointing blacks to minor positions.” But White said that when it comes to “real issues” like teenage pregnancy, housing, and education reforms, “I don’t think they address those issues as much as a black candidate would.”

Hope and Fear

Because voters elect so few black lawmakers, it has been virtually impossible to initiate legislation that addresses the needs of black citizens. “Issues of concern to blacks are met with a negative response,” said state Senator Jerry Jewell. “We don’t control anything in the state.”

Jewell sought public office because he decided to “try and come in and do something from the inside with complete integrity. So far, I’ve only been successful as to the integrity.”

Representative Ben McGee has suffered similar frustrations during his first year in office. “I decided that my role should be just to try and stop bad legislation,” he testified. “We need other blacks in the legislature if we want to actually introduce legislation.”

Linda Whitfield, an unsuccessful candidate for circuit clerk in 1986 and 1988, said that although 60 percent of the voters in her county are black, many feel apathetic about the political process. “They feel their political leadership is null and void. If they are disillusioned, there is no concept in their minds that they can rise above the circumstances.”

Evangeline Brown testified that many blacks in the Delta region still suffer from a “plantation mentality.” Although they are no longer sharecroppers, many feel “the boss is still the boss” and are afraid that their livelihoods will be in jeopardy if they oppose candidates favored by the boss.

“They still do not believe that they can win an election,” McGee agreed. “They do not actively participate in politics because of that fear.”

McGee believes a victory in the voting rights lawsuit will change the hopeless attitude of blacks in Arkansas. He noted that after a 1988 court decision created a majority-black district in his county, about 85 percent of registered voters actually cast a ballot. Blacks living in Mississippi are even more confident, he added, because a voting rights challenge forced that state to redistrict. “Black folk in Mississippi have an expectation that they can win, and they are used to seeing people win, so there’s a lot of participation because the confidence level is so much higher.”

Balance of Power

The plaintiffs in the case want provisions of the amended Voting Rights Act to apply to Arkansas as they do in Mississippi. Specifically, they have asked the court to require Arkansas to obtain “preclearance” approval from the U.S. Justice Department before making any changes in its voting practices or procedures. Many areas with a previous history of discriminatory voting practices are already subject to federal “preclearance,” including Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, and selected counties in Florida, North Carolina, and 11 non-Southern states.

P. A. Hollingsworth, a former justice on the Arkansas State Supreme Court who coordinated the legal team in the voting rights case, said he believes a victory will alter the balance of power in the state legislature. Noting that “there tends to be almost an even split” in votes between legislators from the Delta and their counterparts from northern Arkansas, Hollingsworth said that a bloc of 10 to 12 black votes could act as a “swing vote” or a “veto on issues where a super-majority is required.”

Hollingsworth also said that a black voting bloc could work on a “quid pro quo” basis with white lawmakers from rural northern Arkansas who also represent impoverished districts.

Even if the plaintiffs win the case, however, lawyers warned that it could take a court order to force state officials to draw up new districts.

“If we are successful in this case, the court will ask the current Arkansas Board of Apportionment to draw up new districts that are fair to blacks,” predicted Oily Neal, a Delta attorney who represented plaintiffs in the case. “But the board won’t do it, because two of its members — Governor Bill Clinton and Secretary of State Steve Clark — have future political plans, and they don’t want to be responsible for putting representatives like Senator Paul Benham out of office.”

Tags

Faith Gay

Faith Gay is an attorney in New York City. (1989)