Pay Dirt

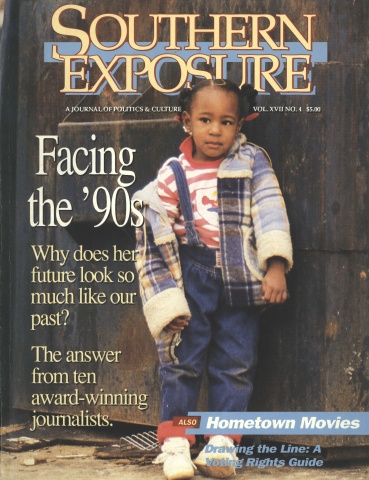

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 4, "Facing the '90s." Find more from that issue here.

Between July 1988 and June 1989, Paul Nyden wrote 175 articles about abuses in the coal-mining industry and weak enforcement by the West Virginia Department of Energy. His articles regularly led to the denial of mining permits and the collection of delinquent fines and reclamation fees. They also helped make mining enforcement a major issue in the 1988 gubernatorial election, in which Gaston Caperton defeated Governor Arch Moore, a three-term incumbent.

Charleston, W.Va. — Six weeks ago, John Adkins, a non-union coal operator from Kentucky, began stripping mountaintops on Winifrede Hollow. Chain-link gates and a guard shack bar local residents from driving up the dirt road to his mines. Department of Energy (DOE) officials have not stopped Adkins from producing coal, despite a federal law that prohibits him from operating a mine anywhere in the United States.

Adkins runs the mines for Fields Creek Coal Company, a subsidiary of Carbon Fuel, which is a subsidiary of the ITT Corp. Adkins’ company, SAAC Industries, has four corporate directors, one of whom is a federal mine inspector. This, too, violates federal conflict-of-interest laws.

Jack Kirk, president of the United Mine Workers local in Winifrede, is one of 800 miners laid off since 1982. Carbon Fuel, then U.S. Steel, scaled down mining operations along the hollow. Today, Carbon Fuel’s huge cleaning plant sits up a side road like a great metal ghost. Two weeks ago, Kirk graduated from the University of Charleston with a degree in nursing. He believes he’ll never work in the mines again, so he’s looking for a job at a local hospital.

“This new company won’t hire us,” Kirk said. “They bring in these outlaw operators from Kentucky. They hire three or four people off the hollow, then bring in the rest from Kentucky. It’s easy to get a permit in West Virginia. The Department of Energy doesn’t check.”

Two days ago, DOE officials were still looking into Adkins’ background, according to Mark Scott, director of mines and minerals, even though federal law requires state regulatory agencies like DOE to finish background checks before allowing an operator to dig the first shovelful of dirt. Kentucky officials did check Adkins’ background: they have prohibited him from operating a coal mine in that state, said Larry Grasch, deputy commissioner of Kentucky’s Department of Surface Mining, Reclamation and Enforcement.

Adkins filed two applications to strip 323 acres in West Virginia. On both forms, Adkins typed “N/A” (not applicable) in response to a question asking whether any company, subsidiary, affiliate, or partnership he operated had been cited for mining violations. Adkins signed the forms and swore to their truth on March 15. Both applications were filed on behalf of SAAC Industries. The office telephone Adkins gave DOE is the number for the main switchboard at the Knights Inn in Kanawha City, West Virginia. Adkins moved out more than two weeks ago.

Adkins has operated several coal companies in Kentucky. Some have long histories of environmental violations. The companies include TAG Coal Corp. (a contract miner for A.T. Massey), Commonwealth Mining Co., A&A Fuels, 4-R Coal, Riley Hall Coal Co., and Templeman and Adkins Coal Corp. Reached at his offices in Chesapeake, Adkins said his mining record in Kentucky is clean. According to Kentucky regulatory officials, Adkins left some of these companies, such as TAG Coal, before environmental violations were cited.

Scott said, “The people in Kentucky told me they did not have John Adkins blocked for any state violations. . . . They did have him down with some sort of a relationship with a company that owed delinquent AML [Abandoned Mine Land] fees. But the information we have is that he may not be responsible for that.”

However, the Applicant Violator System, run by the U.S. Office of Surface Mining, ties Adkins directly to Commonwealth Mining. According to Grasch, Commonwealth Mining has “outstanding AML fees in excess of $53,000. . . . If he applied right now for a permit in Kentucky, he would be permit blocked.”

Adkins operated Commonwealth Mining with a partner, Michael Templeman. In 1986,Templeman opened another non-union strip mine on Campbells Creek under the name Templeman Construction Co. Before coming to West Virginia, Templeman ran up at least $78,437 in unpaid fines and reclamation fees in Kentucky. Apparently, DOE gave him a mining permit without checking his background. When Templeman filed a permit application with DOE on February 20, 1986, he was less than truthful. Asked to list all mining companies he operated during the previous five years, Templeman typed “NONE.”

After Templeman’s mine opened, overloaded coal trucks destroyed a little bridge over Spring Fork. Templeman paid $1,000 toward the cost of replacing it. The Department of Highways paid the rest — more than $37,000.

Within a year, Templeman had disappeared. He left Spring Fork without giving his workers their final paycheck. He never paid $28,000 in fines he owed DOE. He exposed bare 90-foot-high walls around two mountains but never reclaimed them. In June 1988, DOE forfeited Templeman’s $25,000 reclamation bond and revoked his mining permit.

“Nothing Except Wasteland”

Denver Andrews from Pikeville is another business associate of SAAC Industries. Scott said he had never heard of Andrews and that his name doesn’t appear in DOE files. The name does appear on incorporation papers Adkins filed with Secretary of State Ken Hechler on January 26. Andrews is identified as a corporate director and as the individual who receives the company’s legal correspondence.

Andrews is also a federal mining inspector. Richard Leonard, a spokesman for the Office of Surface Mining in Washington, said it is “definitely illegal” for any OSM official to be associated with any coal company. The federal agency is investigating Andrews’ ties to SAAC Industries.

Reached by telephone at the OSM offices in Pikeville, Andrews said he was “good friends with John Adkins and his father, who passed away three years ago.” Andrews praised Adkins’ reclamation work in Kentucky. “His last job here was a picture perfect job,’’ Andrews said.

Labor Commissioner Roy Smith said it was tough to find Adkins. “We have chased these people around. You almost have to be a wizard to locate some of these mines.” Smith said Adkins violated state law by operating a mine without posting a wage bond. When Department of Labor officials found Adkins on Friday morning, he final posted a $40,000 wage bond to cover a

month’s wages and fringe benefits for his 17 employees, six weeks after hiring them.

Mark March, an international representative for the United Mine Workers, said Adkins symbolizes a trend. “I’ve been in eastern Kentucky for two years. It’s common knowledge that if you want to mine coal, you go to West Virginia. It’s gotten strict in Kentucky.” March said Adkins pays employees about $12 an hour, about 75 percent of union wages.

The union was first organized in Winifrede Hollow in 1903. Kirk said the mines there were always union, even while violent mine wars raged nearby on Paint Creek and Cabin Creek in 1912 and 1913, and again in the early 1920s. He said Carbon Fuel has always been the hollow’s lifeblood. “When they hired us, Carbon Fuel told us they were hiring us for life. They said we would retire from here and our sons would retire from here.”

Sitting in the union hall beside the winding blacktop road, Kirk said he’s given up any hope of ever working in the hollow again. He is angry that coal operators come in from other states, bring most of their employees with them, and take their money back.

“These guys hide everything by setting up dummy companies. They get out of their obligations. They take our minerals. They take our money. They don’t leave us nothing. Except wasteland.”

Strings Attached

One thing that coal companies do leave behind is big campaign contributions to top state officials. When Arch Moore Jr. ran for a third term as governor in 1984, coal operators and their friends donated at least $270,000 to his campaign. This year, they gave Moore $150,000 during the primary. They matched that during the general election, where Moore faced insurance executive Gaston Caperton, a Democrat. Including donations from oil and gas executives, Moore has received close to $500,000 from energy-related donors in the 1980s — about 18 percent of the $2.8 million he has raised.

These estimates may be low. Contribution lists, especially those filed in 1984, don’t identify corporate ties of many donors. The total would also increase if other contributors were included, such as mining engineers, lawyers who represent coal companies, and companies that sell mining equipment and supplies.

Jack Hickok, chairman of Common Cause/West Virginia, believes all political contributions come with strings attached. “I am sure people don’t give contributions without expecting something in return. . . . You expect something positive or expect to avoid something negative.” Hickok believes the public ultimately pays dearly for private campaign financing. “We are deluding ourselves if we believe it doesn’t cost us anything when defense contractors are contributing millions to political candidates. And when coal companies contribute to local candidates, we probably pay one way or another.”

Over 90 percent of Moore’s coal donations came from small- and medium-sized operators. Most live in West Virginia. Critics say small operators bought DOE with their contributions, while small operators say they contributed because they believe Moore is good for business and especially good for the coal business.

House of Delegates Speaker Chuck Chambers, a Democrat from Cabell, said, “Larger corporations are used to doing business in many states and are able to protect themselves. Smaller companies may feel they are more at the mercy of DOE. They may perceive the best way to protect themselves is by making large contributions to the governor, who appoints the energy commissioner and other important personnel.”

John Leaberry, Moore’s campaign manager, said smaller coal producers donate because “they are local people who have grown up in West Virginia. They are part of the local fabric of communities here. . . . Somebody like the Justices or the Comptons [small operators] are very substantial members of their communities. Their position on a gubernatorial race is just one aspect of their involvement in the community.” Leaberry himself worked for a coal company briefly in 1987, after resigning as Moore’s workers compensation commissioner.

Illegal Donations

When you thumb through hundreds of pages detailing Moore contributors, controversial names regularly pop up. The list is topped by Kenneth Faerber, the small operator Moore named to head DOE in July 1985. Officers from Faerber’s former coal and reclamation companies also figure prominently.

William Bright, who uses several Wilcox thin-seam mining machines, and Jack Fairchild, who makes them, were Moore contributors in 1984. In 1986, Faerber tried to delay implementing court-ordered safety rules covering Wilcox miners.

The list includes the Addington brothers from Kentucky, who gave Moore $5,000 in April after buying coal lands in the state. The list shows $8,300 in contributions from officials at P&C Bituminous Coal, the company where Leaberry was general manager when it opened its first mines a year ago. And several contributors created serious environmental problems, such as James Laurita Sr., Frank Burford, Joe Burford, Jasper Petitte, John Petitte Jr., Charles Sorbello, Carl Graybeal, Daniel Minnix, and Don Harrold.

Moore’s support from surface miners dates back at least to 1972, when he beat Jay Rockefeller. At that time, Rockefeller lent support to the “abolition” movement to outlaw strip mining. That year, coal companies gave Moore tens of thousands of dollars — legally and illegally.

Coal people also supported Moore’s opponents in 1984 and 1988. Some gave to more than one candidate for governor. Clyde See got more than $103,000 in coal contributions during his campaign for the Democratic nomination. Caperton received over $31,000 from coal executives, including $7,000 from officers of A.T. Massey subsidiaries. His cousin, S. Austin Caperton III, is vice president of Massey Coal Services in Daniels.

Moore raised $874,450 for the 1988 primary — nearly as much as See and Caperton combined. See raised $580,975 and Caperton, $353,319. Moore loaned no personal funds to his campaign committee. See loaned $85,000 and Caperton, $1.8 million, according to reports filed with the secretary of state.

Playing Favorites

What do you get by making apolitical donation? Do you buy influence, or simply a friendly hearing at the state Capitol? Do donations guarantee a break from regulatory officials? Or do you simply buy better, more responsive government?

When Moore appointed him, Faerber said he was an “advocate” for industry. During his time in office, coal production reached its highest level since 1970, topping 137 million tons last year. Faer-

ber said DOE doesn’t favor small coal companies who help finance Moore’s campaigns. “I don’t think you can draw any conclusions on the basis of contributions. They don’t give money in order to get a permit.”

Delegate Thomas Knight, a Democrat from Kanawha who usually opposes Moore and Faerber, also warns against drawing simple conclusions. “Campaigns are very expensive. When someone supports you with a contribution, you will listen to them with a friendly ear. That’s only human. Some take it further and do unusual favors for people. That goes beyond listening,” he said.

Knight believes Moore might be friendlier to small operators, especially since West Virginia deep mine operators supported Clyde See in the 1984 general election. “Political retribution is not unusual,” Knight said. “When it came time to make a critical appointment, Moore made it for his friends.”

Some, such as the United Mine Workers, believe Faerber has sacrificed miners’ safety and reclamation, especially at small mines. They point to similarities between lists of contributors and operators they believe got favors. Although he said he doesn’t oppose higher production, Michael Burdiss, the UMW’s political director, questions the way DOE issued permits.

“Faerber talks about increased production due to lack of red tape. That might mean he is allowing outlaw miners to move into West Virginia,” Burdiss said. ‘The international union has asked Congress to investigate how mining permits are obtained and who receives them to see if there is favoritism.”

Washington lawyer L. Thomas Galloway, who has won several lawsuits requiring more rigorous enforcement of environmental laws, hesitated to comment on the role of political contributions. “But I can say that the decline of the West Virginia surface-mining program has coincided with the Moore administration. During this administration, the enforcement program fell from its position as one of the two or three top Eastern programs to become one of the worst,” Galloway said. “The decline is reflected in almost every major component of the system — initiation of enforcement action, issuing of cessation orders, assessment of penalties, blocking permits to people with outstanding violations, bond forfeitures.”

DOE’s separation from other environmental agencies creates problems, according to Speaker Chambers. “Smaller operators need help to deal with bureaucratic red tape. It can be pretty tough for a legitimate small operator to deal with all the environmental, health, and safety regulations. But this has to be balanced with broader public interest concerns,” Chambers said. “We have taken something as major as the coal industry, probably the dominant factor in the state’s economic and social life, and allowed it to have a separate regulatory program. . . . That is like having one set of state police to check cars on the highways and another set to check the trucks. We only have one environment. When you have major competing interests, which are not balanced and regulated within the same framework, one interest is going to suffer.”

Tags

Paul J. Nyden

Charleston Gazette (1989 & 1997)