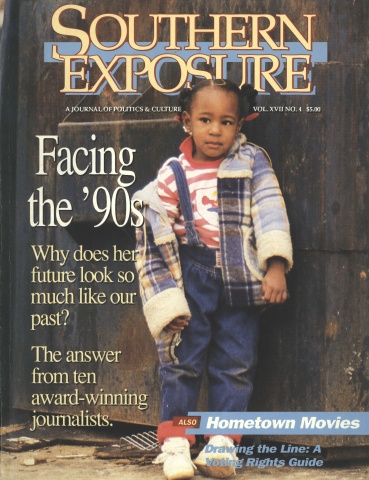

The Face of Poverty

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 4, "Facing the '90s." Find more from that issue here.

From March 26 to 29, 1989, a team reporters at the Herald-Journal documented the extent and depth of poverty in Spartanburg, South Carolina. The series also identified the gaping holes in the safety net that compound the problems of the poor.

Spartanburg, S.C. — Standing shoulder-to-shoulder, they’d stretch eight-and-a-half miles across the city, from Westgate Mall to two miles past Hillcrest Mall. Children and elderly, black and white, they share one thing. Poverty.

The pain shows on their faces, from five-year-old John Anthony, who wants to move out of the housing project, to 73-year-old John Byrd, who wishes he didn’t have to collect aluminum cans to buy food.

The more than 27,000 poor people represent one out of seven Spartanburg County residents, according to the 1980 U.S. Census, the last year for which government figures are available. Most will never escape this underclass, a group many say is greater than estimated and growing.

At age 11, Jeanne DeYoung already has that look, a face stained with the stigma of poverty. Sitting on a thin rug with her parents and younger brother, the Spartanburg girl wrapped her arms tight around her legs and stared at the floor.

Looking over at her daughter, Wanda DeYoung smiled. “We used to have a nice house,” she said. “Split level.” That was before her husband’s kidney operation last fall. Since then, Jerry DeYoung, 45, has been weak, unable to work and without disability benefits, while Wanda puts in 40 hours at a local mill. The $180 weekly income leaves the family in poverty. They pay $15 a week for this bare structure. While the rain pours down outside, the DeYoungs shove old blankets under the doors and windows, sit on the rug near the iron stove, and talk about being in a house again. But Jerry DeYoung knows how hard it will be to find a house. Like an estimated one-third of the households in the county, his family now makes less than $10,000 a year.

The hopes and fears are the same in every shack, housing project, and run-down trailer where poverty leaves its mark. “I wouldn’t blame it on any one thing. If I could just have enough to afford a home for my babies . . . just to get by, that would be good,” said a young Spartanburg woman who did not want to be identified.

That modest wish doesn’t have much

chance in the ninth-poorest state in the nation. Officially, 13.8 percent of the county’s population is living in poverty, but only one-third of those poor people receive food stamps or welfare, the two primary government assistance programs. Statewide, the figure is one-half.

Louise Miller, 40, has experienced the frustration of trying to get adequate help. “I just feel like there’s no hope. I done tried everything in the book, everything,” the Landrum woman said. She and her two boys, ages two and eight, go to the bathroom in a bucket behind their house.

Two national studies have found that Miller’s frustrations are compounded by a state welfare system that makes it even harder to get help here than in most other states. Getting welfare almost always hinges on a person’s income. If the person doesn’t make less than the poverty level dictated by the U.S. government, he or she isn’t labeled poor. “Some work and make a nickel over what the law allows — they don’t get any help,” said Diane McGravy, who manages The Second Chance, a Goodwill Industries outlet store.

Marie Fowler lives just above the poverty line. The 54-year-old employee of Inman Mills lives in a dilapidated, paper-thin house with her son and his family. “When you make too much, you don’t get nothing,” she said, shaking her head.

“Can’t Get No Help”

Those who do get help are jamming assistance agencies. The Haven, a crisis intervention shelter, had 56 percent more people knocking on the door for help in 1988 than the year before, said Jim Evatt, the former director. The shelter closed in December when Evatt became ill.

At the Downtown Rescue Mission, the co-directors believe they could fill 200 beds with Spartanburg’s homeless. Mission worker Dale Guger said that every day they have to turn away people looking for food, shelter, or help with an electric bill.

Even those who get help don’t get enough. Several studies prove that public aid is inadequate and guidelines too complicated. So the assistance checks run out before the end of the month, and that’s when many poor families eat beans until the next check comes. “They expect for the checks to last a month,” said Willie Mae Mitchell, a 46-year-old woman who, like one in five Spartanburg city residents, lives in a low-income public housing project. “It just don’t last.”

Spartanburg County Planning Commissioner Administrator Calvin Byrd said an individual and family would need at least $2,500 more annually than the poverty levels just to provide the basics. For a family of four, the poverty level is $12,100, but it would take about $15,000 for that group to make ends meet here. Likewise, the poverty level for a single person is $5,980, but a person living minimally would need about $8,500.

No one even knows how many poor people live in the county today. Census figures won’t be updated until 1990, and no other agency conducts a comprehensive survey. “We will never know how many people need help because some people don’t want to tell social-service officials how much they make or whether they own their own home,” said James Thomson, executive director of the Spartanburg County Department of Social Services.

But the depth of the problem is clear. Marvin Lare, executive director of the University of South Carolina Institute on Poverty and Deprivation, compares some of the conditions in the Palmetto State to those in Third World countries. Those who live in poverty every day believe it.

“Every damn house on this damn street — we’re all in the same shape. Everyone here crawls into their shell because they can’t get no help, nowhere, no way,” said a 38-year-old Spartanburg man as he looked down a row of run-down houses on Weldon Street.

Shirley LeCounte, who lives in Northside, a city housing project, joins many of her neighbors in walking to the Second Presbyterian Church soup kitchen for lunch. Without that place, she said, many people wouldn’t have one good meal a day. Many of those are young people.

Children carry the heaviest burden. One in every four children nationwide and statewide live in poverty, more than any other segment of the population. They start out with aspirations that rival their middle-class counterparts, but once in school, they fall short, said Clemson University sociologist Chris Sieverdes. The reasons are many, but most never escape the cycle of poverty. They usually don’t even finish high school.

Struggling Biscuit Cook

These issues offer only a glimpse of the trap of poverty. A web of government policies and social agencies, restrictions, and regulations often help the poor but sometimes block out others and intimidate more than a few.

One local woman, who identified herself as the “Struggling Biscuit Cook,” wrote to the Herald-Journal after she received a 20-cent pay raise to $4.20 an hour. “Don’t be in any kind of hurry to get off your benefits,” she wrote. “It’s not worth it. . . . I can’t even make ends meet. I’m the mother of four kids. . . . I was proud to get off welfare, ashamed to go into the grocery store to purchase food with food stamps. But now I wish I had them — you really can’t make it without help.”

Many local poor people don’t understand the qualifications for different programs, or why benefits are cut off. Some don’t know where to go for help, and others are discouraged by red tape, long lines, and complicated forms.

Pride is another obstacle. Many of the poor have worked hard all their lives. They’ve experienced difficulty making ends meet, but they don’t want to ask for welfare.

Yet poverty isn’t a private matter. Last year, Spartanburg County’s Department of Social Services had a budget of $37 million. And poverty touches the public in other places besides the pocketbook. Many crimes are committed as a result of frustration, sociologist Sieverdes said. One 22-year-old Spartanburg man who didn’t want to be identified explained that stealing food or selling drugs was necessary for him as a child. And others defraud the system, or a woman might have another child to get more welfare money.

Still, Sieverdes and local community workers estimated that only about 5 percent of the thousands seeking help abuse the system. The poor don’t want to be where they are. Studies and interviews with about 300 local poor people and public officials by the Herald-Journal over the past eight months show that. More than half of this “underclass,” as they have been called, works full time.

The tragedy extends as far as a person wants to look, because only half of all poor people in the county and across the United States have ever received any cash government assistance, according to a national study, “Holes in the Safety Nets.” Many of the poor, the homeless, and others in need never make it to the agencies to seek aid, the study says. They don’t show up in statistics, and their names will never show up on a list of welfare recipients. “A lot of people don’t want to discuss difficult and private things,” said one middle-aged man at the Downtown Rescue Mission as he helped sort newsletters.

As for the community’s reaction to its poor people, rescue mission worker Guger had this to say: “People in this town know what’s going on. But they don’t want to think about it. But if you don’t take care of cancer, it spreads.”

Mistakes and Red Tape

Agency officials and others say the South Carolina Department of Social Services (DSS) is so plagued by mismanagement and red tape that it can’t even help itself, let alone help the needy. DSS, the state’s public-assistance agency that last year distributed $754 million in state and federal aid, is a source of frustration for those running it, those governing it, and those who seek its help.

The agency’s problems abound and are not easily solved. For example:

▼ South Carolina may have to repay the federal government $46 million because of errors in determining welfare eligibility and payments from 1981 to 1988. Errors cited by federal reviewers include overpayments, underpayments, payments to ineligible applicants, and payments approved under one set of regulations then disallowed under another.

▼ A clerical foul-up in February caused a backlog of 8,176 unprocessed child-support checks, some of which dated back four months.

▼ In December, when DSS installed a statewide computer system in the food-stamps division, the result was long delays, and thousands of clients received their benefits late. The problem has been cleared up.

▼ Barely one in three of Spartanburg County’s 27,177 people living in poverty received welfare or food stamps in 1988.

DSS officials acknowledge they aren’t fulfilling their mission. “I know we are not reaching enough of the needy families and elderly in this community,” said James Thomson, Spartanburg DSS director. “There are a lot of reasons for that, and the biggest one is the bureaucratic red tape we have to go through. We spend more time answering paper work than we do working with the clients.”

But Representative Donna Moss, a Democrat from Gaffney, criticized the department. “There is a lack of communication between county and state DSS officials,” Moss said. “The lack of communication between the two branches of the welfare department just compounds the red tape and management problems. Something has to be done about these problems because I don’t want them to endanger welfare reforms. The taxpayers deserve a welfare system that works.”

“I Want a Break”

DSS administers the food-stamp program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (family welfare), Medicaid health insurance benefits for poor people, and other social-welfare programs, not all of them for the poor. It disbursed $302 million in state and federal welfare dollars out of its $339 million budget. DSS also distributes $451 million in state and federal Medicaid funds. The state agency administers the public assistance programs and provides policy and guidance to 46 county agencies, which are responsible for delivering the services to recipients.

Commissioner James Solomon concedes that his agency is entangled in red tape and rife with inefficiency, but said he is working to improve communications between the local and state DSS offices by streamlining programs and proposing additional staff to reduce waiting time. He said some other improvements are also needed, such as simplifying the paper work required by the federal government. “We have to start working from the federal government level to get some of these problems resolved,” Solomon said.

According to Solomon, “Politicians have to realize they can’t fix the system by adding new regulations, which creates even more paper work than we already have.” A single welfare applicant often must fill out dozens of documents before being considered for assistance.

And there is no guarantee of receiving help. Although the state DSS disbursed three-quarters of a billion dollars last year, only about one in three South Carolinians who qualify for public aid receive it. And frequently those who do receive assistance don’t get enough to provide for their families.

Solomon says the millions in his agency’s coffer are inadequate and difficult to obtain from the legislature because of a negative image of the poor and DSS. “When the Department of Social Services was created, it was to help people who were down on their luck,” Solomon said. “Our society now views public-assistance recipients as deadbeats who just don’t want to work, but that is not true.”

“Some people think that those of us who are struggling want it to be this way, but that is not so,” said Kay Patterson, a Spartanburg mother of two who lives in public housing. “I want to break out of this hard life, but it is difficult when you are refused assistance for one reason or another.”

Some needy families don’t bother to apply for the assistance because they believe it is more trouble than it is worth. Thomson says he is frustrated by the fact that many poor people are too intimidated by the process to seek help, but welfare officials must ask about income and personal possessions in order to make sure applicants qualify. “Each of the public assistance programs has regulations that stipulate criteria,” he said. “Unless [applicants] meet that criteria, you cannot serve those people, and they fall through the cracks.”

All of these factors combine to make it difficult for poor people to get assistance. Welfare officials say it is up to state legislators and Congress to change the system. The lawmakers, though, say the first move is DSS’s. “DSS has promised us that they will correct the problems, and we expect them to do it,” Moss said. “The state DSS is requesting additional funding from the legislature this year to hire more employees. With all of the problems the DSS has had lately, I think legislators will take a long, hard look at the request before just approving it.”

Tags

Diana Sugg

Spartanburg Herald-Journal (1989)

Linda Conley

Spartanburg Herald-Journal (1989)

Allison Buice

Spartanburg Herald-Journal (1989)