This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 4, "Facing the '90s." Find more from that issue here.

The year was 1981. James Burke, a black attorney from Miami, had run for the Florida House of Representatives twice. He had lost both times, defeated by the large white vote in his home district in Dade County.

But now, as state lawmakers prepared to draw new election districts to account for population shifts recorded by the 1980 census, Burke and other leaders in the black community went to work. They pushed for a district that reflected Miami’s black majority — and they won. Dade County became the largest black-majority district in the state, giving blacks 79 percent of the vote. Burke ran again, and this time he won. Eleven other black legislators joined him in the Florida statehouse, giving black voters more state representatives than ever before.

“When the black community needed something, we used to have to beg white legislators who were paternalistic,” Burke recalled. “We’d say, ‘Would you give us a park? Would you give us this or that?’ Now, at least, we have our own voices. We haven’t gotten everything we wanted. But at least we’re there, we’re a part of the process.”

Now, a decade later, Florida lawmakers are once again preparing to redraw election districts. This time, black leaders are aiming their sights at the U.S. Congress, pushing for a congressional district with a near black majority.

“This is the only place in Florida where it can happen,” Burke said. “I think the chances are great. Ten years ago we were just talking about more seats in the state legislature. Now we’re talking about a seat in the U.S. Congress.”

Battle for the Ballot

What is happening in Florida is one of thousands of voting rights battles that have swept the South in the past two decades. In state after state, voters have organized and lobbied and gone to court to demand fair elections for local school boards, city councils, county commissions, state legislatures, courts, and Congress. Since 1978 alone, more than 2,200 voting rights cases have been filed in federal court.

At its heart, the battle for the ballot involves more than what happens on election day — it involves what happens every day in communities across the region. Housing, education, health care, jobs, justice — virtually every facet of daily life is shaped in part by who holds elected office. In this sense, the struggle for voting rights is a struggle for power.

During the next two years, the most important battles in that struggle will be waged in the South. Indeed, much of what happens in state and national politics in the next decade will be determined by what takes place across the region when the U.S. Census begins on April 1, 1990. Using data from the census, each state will redraw election districts to account for population shifts. How those lines are drawn will play a major role in who gets elected for the rest of the decade.

By all accounts, the changes will be monumental. With the population of the South on the rise, the region stands to gain 10 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives — more than in any other decade, and as many as it picked up between 1950 and 1980. According to population projections, four of those new seats will be in Texas, three in Florida, and one each in Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia. West Virginia will lose one seat.

Drawing up new districts will involve fierce political conflict, as incumbents struggle to maintain their seats and blacks and Hispanics fight for districts that reflect their growing numbers. The transfer of votes could empower the South, but it could also leave minorities and the poor with even less of a voice in Congress than they have now. Either way, the battle lines are being drawn now, as Democrats and Republicans prepare to spend millions on the 1990 elections that will determine who will be in office when new districts are drawn — and who will be the judge when the new districts are challenged in court.

House to House

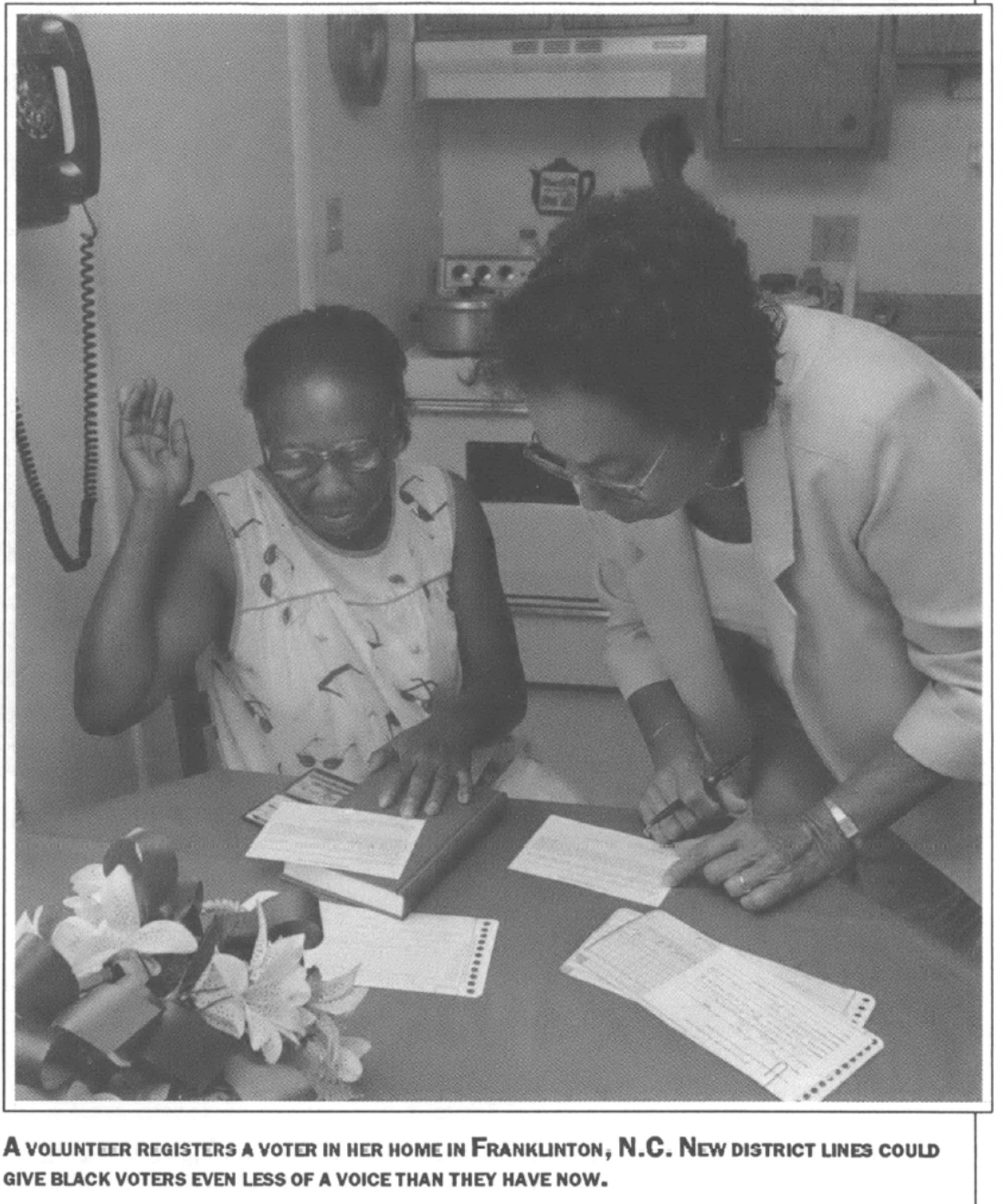

The struggle for the vote has been one of the most widespread yet slowest reform movements of this century, with its roots stretching back to Reconstruction. During the early 1960s, civil rights activists focused on the vote as the primary right from which all others flow. With most blacks barred from the polls by literacy tests and poll taxes, organizers went from house to house urging people to register. They were met with violence, but they stood their ground and focused national attention on the region until Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The law gave citizens the right to sue over discriminatory voting practices, and it required many states to clear any changes in their voting laws with the U.S. Justice Department. The number of black registered voters soared, from 38 percent in 1964 to 65 percent in 1969. In Mississippi, black registration jumped from 6 percent to 67 percent in a decade.

But barriers to fair elections remain. In many places, white leaders responded to the Voting Rights Act by holding multi-district or “at-large” elections that make it harder for minorities to win office. Even though blacks and Hispanics represent more than 20 percent of the U.S. population, they currently hold less than 3.5 percent of all elective offices.

To counter such barriers, voters have challenged hundreds of at-large systems, replacing them with single-member districts that provide minorities with fair representation. The challenges have worked. In Texas, for example, studies show that minority representation has more than doubled in the 60 cities that have adopted single-member districts.

At the state level, voters have challenged legislative districts that fragment black communities among larger white districts. In December, a panel of federal judges in Arkansas ruled in favor of black voters and ordered the state to redraw its districts in time for the 1990 elections — a victory one NAACP leader called “the largest statewide redistricting ever ordered under the Voting Rights Act” (See “Power in the Delta,” page 56.)

Slowly but surely, such voting rights cases have changed the face of politics in the South. Since 1980, the number of black elected officials has increased sharply, from 4,912 to 6,829.

“In a sense, I would not be here if it weren’t for the Voting Rights Act,” said James Burke, the Florida legislator. “Until reapportionment, we never had a black-majority district in the state.”

Family and Friends

Most voting rights challenges start at the grassroots level. And in most cases, they don’t involve an abstract desire for “the vote” — they spring from concrete needs in the community.

For Maxine Cousin, the struggle for fair elections began in 1983, when her father, Wadie Suttles, died of a fractured skull in a Chattanooga, Tennessee jail. Police gave differing versions of how the retired janitor hit his head, but witnesses told Cousin that two white officers beat her father to death.

“When we looked into my father’s murder, we began to discover other people who had been killed in jail,” Cousin recalled. “We began keeping a list — we called it the body count. My father was the fifth black man to have died in four years. Since 1981, 11 people have died in area jails, including a 23-year-old woman who died during pregnancy.”

Cousin and others outraged over police brutality began to demand action from city leaders. “We kept going to the city commission and kept asking them to do something, but nothing happened. We determined that something was seriously wrong with the system. People’s voices were just not being heard.”

Working with Lorenzo Urban, a former coordinator for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Cousin and others began to study the at-large election system in Chattanooga. They researched voting rights cases, studied old newspaper clippings, and collected more than 15,000 documents.

“During our research, we began to realize that the real problem is that black people here didn’t have any political power,” Cousin said. “I just couldn’t believe that racism was causing this. I had to learn what was going on before I realized that the change would have to come from my family, my friends, my community.”

Cousin and her fellow organizers approached the ACLU and took the city to court to demand single-member districts. (See “The Color of Ballots,” page 60.) “We want to show that people aren’t powerless. We don’t have to rely on middle-class groups like the NAACP — we can make some changes ourselves.”

Cousin said district elections will make it easier for neighborhood citizens to run for the city commission, because they won’t have to mount a citywide campaign. “Anybody can run, you don’t need $100,000 to run,” she said. “It will also

hold them accountable to their communities. You’ll be running in your own community among the people you know.”

But Cousin cautioned that the push for fair elections means more than “getting black faces in high places. We want to elect people who are sympathetic to the issues we’re confronting, including police brutality, joblessness, and health care. If they’re not sympathetic to those issues, then they won’t be in office, no matter what the color of their skin. It won’t be controlled, where they have to go to some rich man on the hill to make a decision. We will be included in the decision-making.”

“The Wrong Place”

Many voting rights activists agree that getting blacks elected is simply not enough. Henry Kirksey knows first-hand the limits of elected office. A 74-year-old native of Tupelo, Mississippi, Kirksey was one of the first in the nation to put the Voting Rights Act to the test. In 1965, the year the law was passed, he served as the demographer for a lawsuit challenging election districts in his home state.

Kirksey studied election boundaries and produced evidence to show that they were designed to dilute minority voting strength. But when the case went to trial in federal court, the chief judge was none other than J.P. Coleman, a former Mississippi governor who liked to call himself a “successful segregationist.”

The case dragged on for 14 years, but voters finally won in 1979. That same year, Kirksey found himself running for the state Senate.

“I was sort of pushed into it,” he laughed. “I really didn’t give a damn about it, but some blacks just saw me as the person who was fighting for their rights.”

Kirksey beat a white incumbent, and thanks to the new election districts, 16 other blacks joined him in the statehouse. Unfortunately, political office was not what he expected.

“It didn’t take me more than a few days to realize I was in the wrong place. I’m not very good at begging people to go along with something and then winding up with only one percent of what you’re trying to achieve. I filed maybe a dozen bills each of the eight years I was there, and only one ever got out of committee.”

The problem, Kirksey said, is that even when blacks gain political power, whites maintain their grip on economic power. “Unfortunately, getting blacks elected has not always worked the way it was supposed to. Basically, you really are like anyone else in office — you structure what you do with the idea of staying in office and getting reelected. That means the more controversial things, the things that need the most remedy, don’t get much attention. To a certain extent, what we were hopeful of achieving we have not achieved, in that we do not have a united front against the discrimination that was there then and is still there now.”

The key, Kirksey concluded, is the education gap. “Mississippi has the most undereducated black population in the nation, compared with a fairly well educated white population. Until we can close that gap between the education levels of whites and blacks, we’re not going to get any place. When it comes to power, that’s the greatest power — that’s the winning hand. If you can maintain the education gap, you can maintain all other unequal conditions.”

Black and White

To increase the clout of blacks who do get elected, many candidates are working to build coalitions with white communities. The results can be impressive, as Michael Thurmond discovered when he ran for the state legislature from Athens, Georgia.

Thurmond ran against a white incumbent in 1982, and again two years later, but he lost both times. Finally, he built a successful coalition with whites, and on his third try Thurmond became the first black in Georgia to be elected from a majority-white district in over 100 years.

“We felt we were at a historic crossroads,” Thurmond said. “We had a strong black voter turnout, and at the same time we pieced together a coalition in the progressive and moderate white community.”

Working with the coalition, Thurmond campaigned to ease the fears of white voters. “We discovered that a significant number of whites only go to the polls to vote if they fear a candidate. Many white voters will not vote for a black candidate, even if they support him. They might be for him in their hearts, but they just can’t physically do that. On election day, many did not vote — they just stayed home. In a majority-white district, that’s essentially a vote for the minority candidate.”

Thurmond laid the groundwork for his victory by using the Voting Rights Act to challenge the way district lines were drawn around Athens. After the 1980 census, Thurmond and others pushed for a district that increased the share of black voters from 36 percent to 42 percent. “That was the first step — to get the population represented in the district.”

Thurmond also contested voting rules in court, forcing the county to send registrars into black communities and set the first polling place in a black neighborhood. The moves helped increase voter turnout in the 1985 election, giving Thurmond a margin of victory of 119 votes.

“I would not be in office without the Voting Rights Act,” Thurmond said. “It was only by protecting the rights of the people to participate that allowed me to be elected. It was a long, 11-year struggle.”

Like Cousin and Kirksey, however, Thurmond is quick to point out that getting elected is only the first step. “The question at this point goes beyond having a black in office. You have to have someone who understands how the mechanisms of power can be used to reallocate resources in the community.”

In his first two terms in office, Thurmond has demonstrated that voting rights for blacks benefit low-income whites as well. Thurmond has been instrumental in getting funding for dozens of programs, including money for job training, a new senior center, better mental health services, a day-care center, community-based tutoring, and an extra $1 million in public aid for two-parent homes.

“It helps me to be from a majority-white district, to have to deal with white organizations,” he said. “I have to deal with the reality of white and black life, and I have a better opportunity to come up with a solution that satisfies everyone.”

Political Frontier

If census projections are any indication, coalition-building could become increasingly important during the ’90s. Although the number of blacks and Hispanics in the South is rising rapidly — the Hispanic population is growing five times faster than the rest of the population — a number of barriers stand in the way of translating these larger numbers into increased political power. Among them:

▼ Census data are likely to be flawed. Blacks, Hispanics, and the poor have historically been undercounted in every census. In 1980, blacks were undercounted by 5.9 percent — almost four times higher than the rate for whites.

▼ Population shifts are making it harder to carve out black-majority districts. In many areas, blacks have joined the move to the suburbs, dispersing minority votes across wider areas.

▼ Even when blacks do hold a majority, discriminatory voting rules lower black turnout. According to one study, only 39 percent of Southern cities with 25,000 or more residents where blacks are in the majority have black mayors. As a rule, blacks generally must hold 65 percent of the vote to ensure a victory for black candidates.

▼ Voting rights activists fear that many of the new congressional seats will be awarded to fast-growing areas that are predominantly white, suburban, and heavily Republican. According to the Southern Regional Council, an Atlanta-based group helping state coalitions design new districts, two-thirds of the 31 fastest-growing districts in the South are suburban, more than half are Republican, and 18 showed “strong hostility to progressive interests.” (See sidebar, “The Battle Lines.”)

For these reasons, the biggest gains for minorities may come at the local level. The populations of central cities have become increasingly black since 1970, and the number of black-majority cities is likely to triple after the 1990 census — with most of them in the South. (See chart.)

Whatever happens with congressional districts, observers agree that minorities and progressive whites must place a greater emphasis on building coalitions in the growing number of areas where together they can command a majority of the vote.

“We have to deal with coalitions,” said James Burke, the Florida representative. “To some degree it’s always you vote for mine, I’ll vote for yours.”

Mike Thurmond, the Georgia representative, agreed. “I think we need black-majority districts, but I think the political frontier for black people in the nineties is in districts that are not majority black, but significantly black — districts where you have to form broad coalitions and move outward into the entire community.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.