Care and Punishment

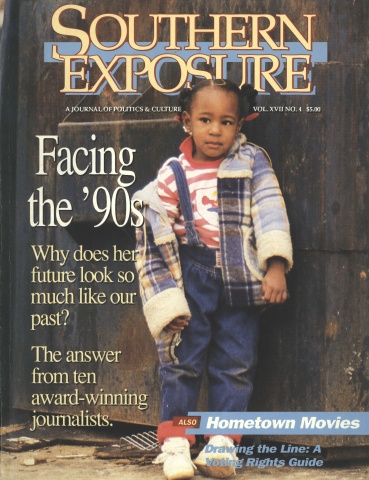

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 4, "Facing the '90s." Find more from that issue here.

The idea for a major series on health care in federal prisons came on December 28, 1988, when a Dallas Morning News editor arrived at the Federal Correctional Institution in Bastrop, Texas. While he waited to interview a convicted bank robber, he noticed an older inmate in obvious pain, his ankles and wrists chained to a gurney in the lobby. The inmate’s face was ashen. He had suffered a massive heart attack on Christmas Eve but had been treated for three days by only a physician’s assistant. Finally, the inmate was about to be transported to a small country hospital to be examined by a doctor.

For a year, investigative reporter Olive Talley dogged the federal system, focusing on the major medical centers in Springfield, Missouri; Rochester, Minnesota; and Lexington, Kentucky. She examined nearly 1,000 lawsuits filed by prisoners in the last five years. She interviewed ill inmates, guards, prison officials, and current and former doctors and nurses who worked for the U.S. Bureau of Prisons.

Inmate Rinaldo Reino, left paralyzed and dependent on a ventilator after a series of catastrophic and incompetent medical procedures in prison, broke into tears at the end of his interview with Talley. “I pled guilty because I was guilty. But I pled guilty to 15 years — not death.”

The series appeared from June 25 to 30, 1989.

Dallas, Texas — Ronnie Holley was a healthy 32-year-old carpenter from South Texas when he entered federal prison for falsifying gun records. He was released early — disfigured and impotent — because of what officials called the “devastating effects” of surgery he underwent at the U.S. Medical Center for Federal Prisoners.

Ben Firth, a 56-year-old former truck driver convicted of hauling cocaine, died of a heart attack at the same medical center in Springfield, Missouri. He had suffered chest pains for several hours without examination by a doctor. A prison doctor later concluded that Firth’s death was likely preventable.

Danny Ranieri, sentenced to seven years in federal prison on a tax conviction, was blinded by an overdose of drugs prescribed by a Kentucky prison doctor whose practice behind bars ultimately cost him his medical license.

Isabella Suarez, in a Chicago federal lockup on charges of stealing mail, lapsed into a coma and died after prison officials withheld her medication for epilepsy, according to inmates incarcerated with her. Charges against the 41-year-old mother had been dropped shortly before her death.

Criminologists and penal experts long have regarded the U.S. Bureau of Prisons and its health care for inmates as the Cadillac of the nation’s network of state and federal prisons. But a Dallas Morning News investigation revealed a medical system plagued by severe overcrowding, life-threatening delays in transfers of in-

mate patients to major prison hospitals, and critical shortages of doctors, nurses, and physician’s assistants. Basic health care for prisoners scattered among 55 federal prison facilities is also thwarted by security considerations, tight budgets, bureaucratic delays, and legal entanglements, The News discovered.

The result is a health-care system that, while providing good care for many, sometimes creates needless suffering and death. The nearly 50,000 federal prisoners find themselves in a “take-it-or-leave it” system in which inmates’ requests for second opinions are rarely granted, even when the inmates offer to pay out of their own pockets.

Dr. Kenneth Moritsugu, medical director of the Bureau of Prisons, says inmates receive a “quality of care consistent with community standards” — a guideline established to meet the Constitution’s safeguards against cruel and unusual punishment. However, many of those close to the prison health system say it lacks the oversight to shield captive patients from incompetent doctors and neglect. More than half the doctors in federal prisons fall into two diverse categories: young doctors fresh out of residency programs — most of whom are paying back the government for underwriting their medical training — or older doctors who have retired from “free world” practices or who previously worked in other government institutions, such as the military or the Veterans Administration.

Unfit for a Dog

Perhaps the single biggest hurdle in providing medical care for inmates is the worsening shortage of doctors. The bureau is operating with 39 vacancies in its authorized medical/surgical staff of 129 doctors. And, according to Moritsugu, the prisons could be understaffed as much as 40 percent by September 1989.

The shortage — compounded by even more severe shortages among registered nurses and physician’s assistants — could reach “absolute crisis” proportions in the next 18 months, Moritsugu said. President Bush has announced plans to spend $1 billion to accommodate 24,000 additional federal inmates by the early 1990s. That 50 percent increase in the prison population would glut the system’s already strapped medical system.

“If there is a significant weakness to the system,” Moritsugu said, “it is the shortage of health-care providers.” Since he took the post as medical director in December 1987, Moritsugu said, he has struggled to hire more medical personnel and make other improvements, particularly in the area of assuring quality. His efforts have been hampered by the inertia inherent in a bureaucracy of 14,000 and by the negative image of prison medicine, which drives away top-flight people.

However, Moritsugu is skeptical of inmate gripes, even though complaints about shoddy health care in federal prisons are voiced not only by inmates but also by private doctors and lawyers and even prison medical personnel. Response by the Bureau of Prisons, critics contend, has come slowly, if at all.

“As a former federal defender and lawyer in this field for 25 years, I can say without equivocation that medical service in the federal prison system is pathetic and unresponsive,” said John J. Cleary, a San Diego lawyer. “I’d be reluctant to take my dog to them.”

David Irvin, a lawyer and former U.S. magistrate in Lexington, Kentucky, won a $625,000 judgment against the Bureau of Prisons on behalf of Jose Serra, whose leg had to be amputated because of what state medical examiners termed incompetent care. “If I were a sick inmate,” Irvin said, “I would feel that my only real hope for treatment would be to get myself outside, either by furlough or to be referred outside for medical care.”

In Chicago last fall, U.S. District Judge Prentice Marshall declined to send a sick defendant to federal prison because of “very disheartening instances” among other ill defendants he had sent to prison and who had not received adequate health care.

It is those beliefs that Moritsugu said he’s working to dispel. “For the most part, when somebody in the general public hears a mention of prison medicine, it raises the specter of dark corridors, bare bulbs, alcoholic physicians who may have lost their licenses in a state nearby and are here at the end of the road,” said Moritsugu, a commissioned officer in the U.S. Public Health Service. “In fact, the standard that we provide to the inmates within our custody is good care, quality care. In some instances, it’s even better care than what an individual who is not an inmate would be able to have access to.”

Indeed, in its year-long inquiry, The News documented many instances in which

prisoners received sophisticated treatment, including heart bypass surgery, cancer chemotherapy, kidney dialysis, and even kidney transplants. Some prisoners have written the Department of Justice in appreciation of the medical care they received. But in other cases, inmates had trouble getting seen by a physician or obtaining the simplest diagnostic tests.

Critics say that problems in prison health care primarily go unchecked because of a weak internal peer-review system, the bureau’s self-imposed secrecy, inmates’ lack of credibility among prison doctors, and the public’s attitude that prisoners deserve whatever happens to them. Prison officials denied several requests under the Freedom of Information Act for documents on internal audits, accreditation surveys, and litigation pertaining to medical care. The bureau also refused to discuss specifics of dozens of individual cases, invoking the Privacy Act.

Diesel Therapy

The News did interview more than 150 people, including current and former prison staffers, past and present inmates, lawyers, and prisoners’ advocates. Nearly 900 lawsuits were examined in the federal jurisdictions in which the Bureau of Prisons’ largest federal prison medical facilities are situated. Among the findings:

▼ Full-time doctors are not available at all 55 prison facilities. In some smaller prisons, inmates have access only to physician’s assistants — medical personnel trained to screen but not treat patients — who decide whether the prisoners need to be examined by doctors. As a result, many inmates do not get prompt, proper diagnoses.

Inmate Larry Allphin, for example, said he complained for five months of nausea and abdominal pain at the penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana; physician’s assistants accused him of faking. Only when Allphin had urinated two units of blood in a matter of hours did a doctor see him. The doctor diagnosed Allphin’s illness as cancer; he died two years later at age 38.

▼ Even when illnesses are diagnosed, treatment often is delayed so long that the illness becomes life-threatening. Sidney Mayley, 32, serving 25 years for bank robbery, had a history of cancer and had previously had surgery in prison for lip cancer. But it was six months after he notified officials of a suspicious lump on his jaw before he underwent diagnostic tests in Rochester, Minnesota. An outside doctor found that only immediate surgery could save Mayley’s life, and an operation was performed within 24 hours. Mayley recently underwent reconstructive surgery and is recuperating.

▼ Despite a government airlift operated jointly by the Bureau of Prisons and the U.S. Marshals Service, ill inmates — including some emergency patients — undergo long, circuitous trips to reach prison medical centers. Prisoners assigned to bus transfers — which they call “diesel therapy” — are shackled at their hands and feet and chained to their seats for hours-long rides under conditions that one former federal magistrate described as “the pits.” Some female inmates have complained of being denied sanitary napkins while in transit.

In one example documented by a prison doctor, federal officials last year sent a critically ill inmate — one with bleeding around his brain — more than 300 miles by ground ambulance from Kansas to Missouri, yet transferred an anemic inmate by emergency airlift.

Last December, the government paid an undisclosed settlement to the family of Vinnie Harris, 31, of North Carolina, who died of asphyxiation after a guard taped his mouth shut with duct tape during a bus transfer. Another inmate, August Mazoros, suffered sudden cardiac arrest and died within 24 hours of his arrival at Rochester. According to a lawsuit filed by Mazoros’ family, the attack occurred after a 12-hour bus transfer from Springfield.

▼ Medical records often do not accompany inmates — even emergency patients — when they are transferred for medical care. In the case of one inmate sent to Springfield, former staff internist Dr. Dante Landucci wrote that “the patient arrived with so little documentation that it was impossible to know where he came from, let alone what was wrong with him.”

▼ Some doctors who practice in federal prison lack U.S. medical training or board certification to perform specialty work they practice. Jose Serra won his $625,000 judgment against the government after medical experts testified that his leg had to be amputated because of Dr. Paul Pichardo’s delays and failures in treatment of Serra’s vascular problems. The Mexico-trained doctor lost his license after the Kentucky medical licensing board determined he had failed to give Serra proper care.

▼ When confronted with evidence of malpractice or neglect, prison officials have responded slowly, if at all. In the Serra case, according to a former prison doctor, officials allowed Pichardo to resign rather than fire him, even after judgments against him totalled nearly $1 million.

Some members of the Springfield operating room staff were so concerned about the qualifications of one surgeon that they filed formal protests with the hospital administration. The complaints came after what staff members termed a wrongful death. The administration rescinded some of the surgeon’s operating privileges but allowed him to continue other kinds of operations.

For 13 years, the bureau has fought a lawsuit alleging the wrongful death of a Terre Haute inmate who died within 10 minutes of being administered what his family’s attorney alleged was an inappropriate drug for an asthma attack. The inmate’s family says the prison doctor ordered the drug over the telephone without examining the patient. The doctor recently resigned from the prison system amid pressure from a warden dissatisfied with his performance, said a source within the prison system.

▼ Overcrowding, understaffing, and rising health-care costs exacerbate the burden of providing medical care. According to the bureau’s calculations, its facilities are overpopulated an average of 60 percent, with some units, such as the Metropolitan Correctional Center in Miami, overcrowded as much as 154 percent. Overcrowding is particularly acute at minimum-security camps: the newly opened Bryan, Texas, camp is overcrowded by 224 percent.

As the number of people convicted of federal crimes grows — particularly in drug cases — and juries become more aggressive in sentencing, prison officials project that the inmate population could top 100,000 by the turn of the century. The number of inmates grew 75 percent in the five years ending in 1988, while staff levels increased only 23 percent. Between 1980 and 1988, the cost of outside medical care for inmates rose 505 percent to $20.7 million.

In addition to 39 vacancies among medical and surgical doctors, the bureau cannot fill 42 of the 250 authorized nurses’ jobs and 179 of the 400 authorized positions for physician’s assistants. At the Federal Correctional Institution in Milan, Michigan, the authorized medical complement is 17, but one doctor and two physician’s assistants currently provide care for over 800 inmates.

900 Lawsuits

Prison officials say that relatively few of the hundreds of lawsuits filed by prisoners each year pertain to medical care, reflecting prisoners’ satisfaction with the overall medical care they receive. However, officials refused The News’ request under the Freedom of Information Act for nationwide statistics on lawsuits filed against the agency. The agency said its records on lawsuits are computerized in files containing other information that is exempt from public disclosure.

However, inmates and defense attorneys argue that most medical complaints never make it to the courthouse. Many inmates don’t have money to hire lawyers. Other inmates fear reprisal. And many prisoners — and even lawyers — say they are daunted by the complexities of prisoner lawsuits that require inmates to exhaust lengthy administrative appeals before going to court.

Another barrier to lawsuits, critics say, is that prison doctors have immunity from personal malpractice claims as long as they are working within the scope of their duties. Unlike proving negligence against a private doctor, inmates also must prove that the prison system showed “deliberate indifference.” Thus, a prisoner could prove that a doctor was negligent but still not recover damages.

Even when inmates get their cases heard in court, they almost always lose. Of nearly 900 lawsuits The News examined, less than two dozen resulted in favorable rulings for inmates.

Legalities aside, observers of the prison system say medical care behind bars inevitably is tinged by the abiding hostility between inmates and their keepers. “It’s not just the bureaucracy, but the attitude which prevents [inmates] from obtaining treatment,” said New York attorney Nathan Dershowitz. He represented Anne Henderson-Pollard, the wife and accomplice of convicted Israeli spy Jonathan Pollard, in an unsuccessful lawsuit alleging that she has received inadequate medical care.

Lawsuits filed by prisoners often reveal the depth and sometimes absurd consequences of that struggle for power. Springfield officials refused to allow inmate Clifford Redwine, a 63-year-old World War II veteran convicted on civil rights charges, to spend his own money on orthopedic shoes. Redwine, according to his lawsuit, had owned one pair of orthopedic shoes for 10 years and had worn them in state and federal prison for the previous three years before they wore out.

“Common sense may be at a premium here, but it would seem that permitting petitioner to buy the . . . medical shoes at his own expense would be the logical solution to this dilemma,” Susan Spence, an assistant federal public defender wrote on Redwine’s behalf. After 18 months of legal wrangling, a judge granted Redwine’s request.

Chicago attorney Jeffrey Steinback, who has represented dozens of inmates in federal prisons, said the tug of war between inmates and jailers sometimes becomes so intense that authorities withhold medical treatment as punishment “You’re a malingerer, or I don’t like you — so suffer,” he said, describing the jaundiced attitude of some prison doctors.

Doctors and nurses say, however, that it is difficult to sort out real symptoms from staged ailments, especially among a group of people who are largely manipulative, uneducated about their own physical wellbeing, and who distrust any medical diagnoses they receive.

And medical staffers — even the guards — walk a tightrope in a monolithic system that makes no allowances for individuals, said Ivan Fail, who before his recent retirement spent 29 years as a guard. “We’ve got some damn good people in this system. . . . They don’t want to be conned by inmates, but they’re terrified of government retaliation.”

In 1983, superiors criticized Fail for providing a wheelchair — against a doctor’s orders — to a convict who was dying of cancer and too weak to walk to the X-ray lab. “It was the humane thing to do,” said Fail.

Tags

Olive Talley

Dallas Morning News (1987)

Dallas Morning News (1989)