Bottom of the Class

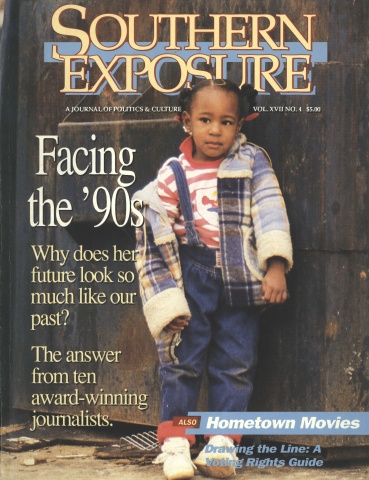

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 4, "Facing the '90s." Find more from that issue here.

Alabama’s public schools are in trouble. From elementary schools without libraries to teachers without basic supplies, the schools are being asked to do more with less. An inequitable tax structure, a legislature that puts politics before pupils, children of poverty who start behind and never catch up — all are part of this complex problem, the subject of a four-month investigation by the Alabama Journal.

After the 11 -day series ran, the governor reactivated an education study commission to recommend funding avenues in 1990. He also included a provision in his budget to allow county commissions to raise local property taxes through referenda without the legislature’s permission. At least half the money raised from those referenda would go to education. But some legislators have criticized the governor for not including more provisions for raising local taxes for schools.

Montgomery, Ala. — Some hard lessons are being taught in the state’s public schools. They aren’t lessons teachers have prepared, but they are lessons of economics, politics, and history.

If public-school children could comprehend these lessons, they would learn that economics largely determines their chances for a good education.

They would learn that at the same time the public cries for greater commitment from teachers, administrators, and pupils, Alabama’s financial commitment per pupil is fourth lowest in the nation.

And they would learn that Alabama’s constitution sidesteps any guarantee of public education.

Some Alabama public schools hold their own in comparisons of pupil scores throughout the country, but other schools are at the bottom of the class in every educational category.

Tates Chapel Elementary School, tucked in the hills of southwest Wilcox County, is part of a school system where less than adequate has been allowed to be more than enough, according to teachers and residents. The school, which has no library, houses kindergarten through sixth-grade classes — even though the state Department of Education recommended closing it four years ago.

Principal James Gildersleeve hesitantly compares his school and the public schools in Mountain Brook, an affluent city near Birmingham. In Mountain Brook, classes are small, funding for education is a priority, and most parents are well-educated professionals. Mountain Brook student scores average in the 80th to 90th percentiles on standardized achievement tests, meaning only 20 percent or fewer students in the nation score higher. Wilcox County scores are near the 20th percentile.

Mountain Brook schools offer computer courses, art, and a range of foreign languages and special classes. Many Wilcox County students do well to have textbooks of their own.

The economics of the schools reflect the communities of which they are a part. Walking across a large parking lot at Mountain Brook High School, a school administrator said, “I’ve been told this is the only school in the state where every kid drives two cars to school.” Most of the students in the Wilcox County school system ride school buses.

Rich and Poor

Wilcox County’s heritage is one of rich Black Belt soil, stately plantation homes, and slave labor. Private schools educate most local white children. “Most of our students are low-income, disadvantaged,” said Gildersleeve.

What does that mean for students? Gildersleeve said it means they need more and get less.

While many schools and many of the 720,000 students in Alabama have made strides in recent years, a four-month investigation by the Alabama Journal shows that the state’s public schools suffer from inadequacies and inequities that in many ways result from a lack of commitment to public education. The Journal found that:

▼ In many of Alabama’s poorer rural counties, even the best students lack basic reading and writing skills. Many students come from homes with no books or role models for academic achievement. Children enter the school system with poor communication skills. And schools do not have the resources to reverse a legacy that spans generations.

▼ In the 1986-87 school year, Alabama ranked 48th in the nation in the amount of money spent per pupil — $2,610 each. Alabama ranked second behind Mississippi in the amount of federal funds it receives as a percentage of total school revenues.

▼ Alabama has the lowest property taxes per person in the nation. Property taxes are a prime source of local funds for schools.

▼ Landowners work to keep property taxes low, reducing revenues available to fund public schools. Some of the poorest counties are those where the fewest number of landowners control the most land. In Wilcox County, 10 percent of the landowners control 71 percent of the land, according to a University of Alabama study.

▼ The Alabama Farmers Federation and the timber industry contribute funding and voices to defeat local property-tax increases for schools. They contribute heavily to elect state officials to protect landowner interests. Governor Guy Hunt’s 1986 gubernatorial campaign benefited from $83,493 from the Farmers Federation and at least $18,554 from the state forestry political action committee and timber-related companies.

▼ For many years, state officials and others bragged about the state’s low property taxes, but some are beginning to assert that reliance on sales, income, and other taxes has left the state with an inequitable tax structure. Forest and farm lands make up more than 85 percent of the state’s 32 million acres but account for only 17 percent of the state’s tax base.

▼ Legal experts say unless the state moves quickly to correct inequities in school funding, it could face costly litigation.

▼ Many Alabama schools aren’t integrated because of a complicated mix of racism, class differences, and fear. Political leaders have shown little interest in overcoming these barriers.

▼ Alabama’s average teacher earns $5,000 less than the average teacher elsewhere in the United States, but many say they’d prefer better and more materials to a higher salary. They’ve come to accept low pay, overcrowded classrooms, poor materials, and inadequate budgets as part of the job.

▼ Some school teachers drive school buses to supplement their salaries, and many have used personal money to purchase classroom supplies.

▼ The requirements to be a teacher in Alabama have been reduced to one: graduation with a C-plus average from a college teacher-education program.

▼ About 370 of the 391 public high schools in Alabama field football teams. But only 286 public high schools offer a foreign language class, and fewer than 100 offer a computer class.

▼ The state’s economy is tied to the quality of education possessed by its students, and unless educational standards are improved, the state’s economy will be crippled by an abundance of under-skilled workers.

▼ Across the Southeast, state after state has moved to reform its educational system. Based on the experience of these states, it is clear that a strong leader, such as the governor, is required as a first step to creating meaningful reform. Governor Guy Hunt hasn’t demonstrated such leadership, nor has he been able to heal a fractured state political system.

Money and Politics

The problems of public schools are complex.

Pumping more local funding into the schools is one solution. In Wilcox County, for example, the biggest local resource is pine trees and products made from them. But because of low property-tax rates and low property assessments, the resource that could provide more funding for schools is largely untapped.

Wilcox, the county often eyed as having one of the worst educational systems in the state, is not alone. In Albertville, in Marshall County in north Alabama, the tax base is more stable and student scores are good, but local residents recently refused to raise property taxes to build and renovate schools. The state fire marshal has threatened to close some antiquated school buildings there, but that didn’t convince voters more money was needed, says Dr. James Pratt, superintendent of the system.

Politics at the state level further complicate providing a good education. Some teachers were left hanging earlier this year when the legislature — ironically in a session dubbed an “education summit” by Hunt — failed to approve a state education budget during the regular legislative session. Some of those teachers were lost to other states.

And in parts of Alabama, schools still basically aren’t integrated, often because whites continue to enroll their children in private schools, as in Wilcox County. Education experts admit that integration in the 1960s created a backlash by many whites against public schools, and the impact on perception of public schools lingers.

For those reasons and more, it would be almost impossible to correct everything that is wrong with public education in Alabama with one piece of legislation or one state school-board resolution or one task force or even one term in any political office. But education and business leaders agree that if Alabama is to fill a future role of something more than a developing nation — providing unskilled workers for low-paying jobs — the educational needs of the people of the state must be addressed.

Timber and Taxes

Principal James Gildersleeve boasts about the two-classroom structure behind Tates Chapel Elementary School. The building he is so proud of is part of MacMillan Bloedel Inc.’s legacy to the education of Wilcox County’s children. MacMillan Bloedel is a large timber company, with operations near Pine Hill. Fourteen years ago, Gildersleeve got the company to donate the lumber for the building, which houses a special reading class and a third-grade class.

While Gildersleeve considers the lumber he got from MacMillan Bloedel a windfall, the timber company owns 22,034 acres in the county and leases about 60,000 more, which means it has access to and reaps profit from about 13 percent of the land in the county. MacMillan Bloedel paid $162,508 in property taxes last year on its acreage and other property in the county. Of that, about $35,876 was for the county schools. MacMillan Bloedel is one of Wilcox County’s biggest landowners.

Because of exemptions, low millage rates, and appraisal rules that favor agricultural and timber land, some officials believe the timber interests don’t pay their share in supporting the community, particularly the public schools. But MacMillan Bloedel president Wyatt Shorter emphasizes that his company pays income and sales taxes and does what it can to help the local community. “We’re long-term citizens,” he said. He said he cannot judge whether his company pays its share of the property-tax burden. He would not reveal the company’s annual profit.

Local residents seem hesitant to bite the hand that feeds them, even if it is providing only part of the support it could. MacMillan Bloedel is the county’s largest employer. It employs 1,200 people, with about a third of those from Wilcox County. Businesses related to the pulpwood, paper, and lumber mill, including hauling and other contractors, provide many more jobs.

“They can’t be expected to take care of everything. They’ve done pretty good,” Gildersleeve said of the timber company. “We do a good job under the circumstances.”

The circumstances are too few teachers, books, and supplies, too little space, and too few ways to help underprivi-

leged students. At Gildersleeve’s school, there is no library. Fourth- and fifth-grade students were crowded into one classroom last year, and this year, the same students have class together as fifth and sixth graders. The water fountain is a bare spigot outside.

The teacher and teacher aide in the classroom try to keep order, but noise from about 40 children and from fans that stir the dusty air makes it difficult for some children to hear or focus on lessons. One blackboard hangs on a paint-peeled wall at one end of the room. A large heater takes up one corner. Students in the back squeeze between desks to reach the chalkboard for math problems.

Lillie Snell, the teacher aide in the class, said it is difficult to teach in the packed room. “There are too many in there. We have 40,” she said. “It is too many.”

“Some children don’t have enough books and supplies,” Snell added. “If each child had a book, it would be better.” She said the children would take learning more seriously if conditions and supplies were better. “The classroom just has too many children to help the children like they’re supposed to be helped.”

White Flight

Wilcox County historically has expected little from its public schools. And little is what children have received. Test scores are among the worst in the state. Wilcox County 10th graders averaged in the 19th percentile on 1987 standardized achievement tests. The average was even lower on certain subjects, including reading and science.

Many teachers in the system know their students have trouble reading. Some teachers are disillusioned about how to solve the problem. “We have trouble getting them to read,” said Joann Young, an English teacher at Wilcox County High School in Camden. Finishing homework also is a problem, she said. “There’s a lack of motivation.” Many students do not see education as important since it isn’t stressed at home, she said. In many instances, parents can’t read or simply don’t like to read. “For a lot of students, [school] is just a way of getting out of the house.”

“We do not have adequate books,” Young said. The material in use has only a few exercises for each grammar concept or story. “Our students need more than that to grasp what we’re trying to teach,” she said. She wants a basic English book she can use to help students with individual problems.

Like other school superintendents throughout the state, Wilcox County Superintendent Dr. Odell Tumblin said her system is underfunded. “Local support is low.” Yet people ask her, “Why is Wilcox so poor? Why is Wilcox so segregated? Why is Wilcox so substandard?”

Tumblin said the problems of the school system are part of a divided community where most people with political power and financial means care little about the public schools. Their children attend private schools, she said. Almost all white students go to one of three private schools. Twenty-eight white students attended Wilcox County public schools last school year. White flight after integration in the 1980s left the public schools without funding or community support.

Tumblin contends that the power structure drains resources from the public schools to use in the private ones. But the Wilcox County Commission’s attorney, George Fendley, said such accusations are unfounded. Fendley’s children go to private school, and his father helped start two private schools in the area. “I’d love to be a proponent for the public school system, but the way their test scores are, I don’t think they’re very good,” said Fendley. He said people send their children to private school for the sake of their education.

“Few people are willing to talk about it,” he said, referring to the separate school systems. Whites are afraid of being labeled racist, and blacks don’t want to be labeled anti-white. And Fendley said he doesn’t see communication opening up or things changing.

Wilcox County is about 71 percent nonwhite. Wilcox has the fourth lowest per capita income of Alabama counties. Yet the county has an abundance of pine trees, the resource that feeds the state’s largest industry. According to “Land Ownership and Property Taxation in Alabama,” a University of Alabama study, 10 percent of the landowners in Wilcox County control 71 percent of the land there.

Families who have owned large parcels of land on the area’s rivers and passed it down through generations since plantation days still hold many acres among brothers and sisters, fathers and sons. For example, several Wilcox families — the Hendersons, Bonners, and Schutts — own more than 6,000 acres apiece, according to 1987 tax-assessor records. Much of that is in timber. Paper and pulpwood companies, like Scott Paper Co. and Gulf States Paper Co., also own significant acreage.

Cheap Trees

Forestry and farming interests — the Alabama Forestry Association and the Alabama Farmers Federation — work at the local and state level to keep property taxes down. They continue to do so even though county and city property taxes are the primary means of local support for education.

One of their successes was the 1982 “current use” law under which timber and agricultural land is appraised at a lower rate than its fair-market value. According to the land ownership study, timberland is appraised at an average of $227 an acre. That would yield 59 cents an acre in property tax, while timberland appraised at highest use, an estimated $15,000 per acre, would yield about $78 an acre.

In addition to that, MacMillan Bloedel gets tax breaks under the Wallace-Cater Act, which exempts the company’s $500 million production plant from property taxes as long as the company owes money on the bonds sold to build it.

Currently, Wilcox County levies a 20.5-mill tax on property in addition to the state’s 6.5 mills. Six of the county’s mills go to the county school system, but because of lawsuits and courthouse errors, the county has collected as little as 3 mills for the schools at times over the past few years. The amount collected fell to 3 mills again October 1 as a 3-mill tax measure that went into effect in 1968 expired.

With 2,878 students enrolled in its public schools, the Wilcox system’s annual budget seems to be healthier than those of some other school systems when the budget is compared to the number of students. The system’s 1987-88 budget allocated almost $9 million. Wilcox spent more per student than the state average in the 1986-87 school year, according to state Department of Education figures. Tumblin attributes that to dwindling enrollment. The Wilcox county school system also receives a boost from federal funds. But with local millage dropping to 3 mills, local revenues will fall.

Some legal experts say Alabama could be setting itself up for lawsuits over inequitable school funding, which has been challenged in other states. Richard Cohen, legal director of the Southern Poverty Law Center, said Alabama’s school funding system could be challenged. “I certainly think that the longer the legislature puts off reforming the system, the more likely it is to end up in federal or state court. To avoid the hazards of litigation, people would be wise to put their house in order.”

While school systems with broad-based local support and funding expand course offerings to include computer classes and several foreign languages, Wilcox County schools struggle to provide the basics. For the first time in its history, the Wilcox County school system has a school — J.E. Hobbs Elementary School — accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. School officials are working to get another school, Pine Hill Consolidated School, accredited. Tumblin said that will improve the education of children going through the schools now.

At Wilcox County High School, conditions are dismal. A dark hallway lined with broken and dented lockers leads to 11th- and 12th-grade classrooms. Leaky ceilings, cracked windows, and broken doors illustrate the overall condition of the school.

Wilcox County high-school students are slated to move into a new, $7.5 million consolidated high school (there now are three high schools) this year. The school is being built using state Public School and College Authority funds, a pool of money doled out by the governor, state school superintendent, and finance director for school construction. However, some residents complain that when the school is finished, students will have to be bused hundreds of miles each day. And Fendley said he doubts that the move into a new multi-million-dollar school will improve the education offered the county’s public school students.

Tags

Emily Bentley

Alabama Journal (1987)

Allan Freedman

Alabama Journal (1989)

Janet Jimmerson

Alabama Journal (1989)