This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 4, "Facing the '90s." Find more from that issue here.

Betcha anything that Beaner’s science project is an atomic bomb.” That was just one of the rumors making the rounds at Bayside High School during the last week in April of 1962. Mary Helen Dumont had heard the bomb story from someone who’d heard it from someone who knew Beaner’s older brother and was certain beyond any shadow of a doubt that Beaner intended to incinerate the school — and maybe the entire town of Bayside. It was a terrifying possibility: five thousand souls vaporized by a belligerent, unpredictable teenager. I admit to having been a trifle surprised that these rumors didn’t occasion more concern among the majority of students and the school administration; I surmised, finally, that they were inclined to dismiss such gossip as nothing more than adolescent malarkey, the kind of teenage puffery no one takes seriously. But if they’d been in classes with Beaner for most of their lives — as had many of the students in the junior class and all of us in Mr. Clingfield’s physics course — they would have been digging fallout shelters. We knew that Beaner Murphy could construct a bomb — maybe even an A-bomb — if he put his mind to it.

By the time I’d entered elementary school, Benny “Beaner” Murphy was already a playground legend. I had heard from older children that he had beaned his teacher on the head with a looseleaf binder on the very first day of first grade and had been sent to the cloakroom for the remainder of his natural life. I knew, also, that Beaner lived with an alcoholic mother and a worthless older brother named Dixon in an unpainted row house on an oyster-shell alley that ran behind the A&P store. Mother characterized the denizens of this section of town as “less than worthless,” and I was forbidden to ride my bike down the street where the A&P was located. So my knowledge of Beaner’s home life was gleaned from fleeting glimpses as we drove by the A&P on Saturday mornings and from the half-truths and outright lies that were the mainstay of small-town existence.

I understood early that Beaner’s paternal origins were in doubt. The men of town — especially those who worked the water for a living — were given to making jokes about it. “I swear one of them Murphy boys has got your eyes,” I overheard one waterman say to another as I baited my crab lines on the town pier one summer afternoon. “Well, if he’s got my eyes, he’s sure as hell got your ears,” the other rejoined. And Beaner’s mother — a more abstract personage than her flesh-and-blood son — was the subject of much unflattering parlor gossip at Grandmother Botts’ house. “Well, I’ve heard tell that she’s got a different man there every night. She’s probably doing you know what for money.”

I caught up with Beaner in the sixth grade. He had waited there two years for my arrival, being in age that many years my senior. He might have remained indefinitely in the sixth grade except that the teacher who had twice failed him on the grounds that he was a “potential felon” eventually arrived at the realization that she would end her days tormented by Beaner if she didn’t promote him.

In appearance, Beaner was pure cliché: greasy black hair that rose sidewise in cresting waves that broke on top of his skull and curled luxuriously onto his protruding forehead, piercing Irish-blue eyes deep set in shadow, and a long slender nose, pointy as his chin. He was of slim build, small-boned and wiry, and he wore only T-shirts, blue jeans, and a black leatherjacket. But Beaner’s most intimidating characteristic had more to do with his reputation than with his appearance. There was about him an air of danger, a razor-quick edge of unpredictability that keened-up one’s senses. Certainly he was what Principal Hanson referred to as an “agitator”; he constantly disrupted classes and tormented teachers, administrators, hall monitors, cafeteria employees, crossing guards, janitors, whimps, simps, nerds, dipshits, geeks and pissants — all those people he lumped into a group he referred to simply as “lunchmeat” — with a myriad of intimidating gestures and noises — incidental glances, gawks, growls, scowls, coughs, farts, sighs, etc.

I soon discovered, however, that there was a more complex facet to Beaner’s character. One morning, as Miss Coy, our sixth-grade teacher, was reviewing pronoun-antecedent agreement, I looked over and noticed that Beaner was reading from a book concealed in his lap. I assumed, naturally, that he was engrossed in, at best, a Mickey Spillane detective paperback, and at worst, one of the “smutty” novels that was in those puritanical days, all the snazz — maybe Peyton Place or Fanny Hill. At recess Beaner scuffed out onto the playground, and I slipped the paperback out of his desk. It was entitled Nausea and was written by Jean-Paul Sartre. I leafed slowly through the pages expecting to find the obscene passages clearly marked, but discovered instead underlined paragraphs and accompanying margin notes: “Looking back before birth and into the very reality of death” and “The synthesis of final reality” written in the same scrawl used to scratch graffiti above the restroom urinals. Synthesis? Final reality? Clearly, there was something going on with Beaner that I did not comprehend.

For the next few months, I continued to slip books out of his desk during recess, encountering such memorable titles as The Restlessness of Shanti Andia and The Medieval Mind. One morning as I flipped through Beaner’s copy of Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, he caught me. “Get your ass out of my business!” he barked, grabbing me by the shoulder. I was so startled by his sudden appearance that I stumbled over my own feet and went sprawling onto the floor. The rest of the class was on the playground, and I thought for a moment Beaner might jump on me and pound me bloody, but he just stood over me, with a look of pure loathing in his blue eyes. Just then Miss Coy happened into the room and screamed, “Beaner, I’ve had it with you! You’re going to the principal’s office! I don’t intend to have this rough housing in my classroom!”

I pulled myself up and brushed myself off. “Beaner didn’t do anything,” I said. “I just stumbled over my chair and he was helping me up.”

Beaner looked at me, his eyes dark with anger.

“That’s a likely story,” Miss Coy said.

“It’s true,” I said.

“Is that what you were doing?” she asked, staring at Beaner.

He did not reply.

“All right,” she said, finally. “But if I catch you two misbehaving again, you’re out of my class. Do you understand me?”

“Yes ma’am,” I answered. I would like to say that this act of self-sacrifice — based though it may have been on self-preservation — endeared me to Beaner, but this was not the case. And for the next four years I kept my distance.

By the time we were in Mr. Clingfield’s junior physics class, Beaner was openly reading The Cherry Orchard and Elements of Chemical Thermodynamics, and I had grown accustomed, as had my classmates, to the obvious dichotomy in his character. Probably Mr. Clingfield never noticed Beaner’s reading material. Short on pizzazz and long on whisky burns, he was attempting to exit the system without expending any unnecessary energy or attracting unfavorable attention. Mr. Clingfield had only to make it through the year before he could retire with his reputation intact. Much to everyone’s surprise, he had been assigned to teach the PSSC (Physical Science Study Committee) Program, a progeny of the great Sputnik panic of the late fifties. It was common knowledge among the students and faculty at Bayside that in the sanctuary of the teachers’ lounge Mr. Clingfield nipped frequently from a flask he secreted in his jacket pocket.

On that first day of school, he took one look at our young faces, sweet faces, pulled his pink nose, and focused on Beaner. “You,” he said, pointing, “you’re in charge here until I return. I’ll be in a meeting in the teachers’ lounge.” And he was out the door, his hand tapping lightly his jacket pocket.

No one moved. No one spoke. In the years we had been in school with Beaner, he had never been placed in charge of anything. Now he was in charge of us. Five minutes passed, ten, fifteen. Finally, Beaner closed his book and scuffed to the front of the room. He hooked his thumbs in his belt loops and rocked forward slightly on the balls of his feet. “Listen up, lunchmeat. From now on, you’re going to do what I say to do and if anybody blabs, he’s dead. Understand?”

We all nodded.

“Okay. You play it my way and you get a good grade in physics. You cross me and you get a frog on your permanent record.”

We stared.

“Today, you do whatever the hell you wanta do as long as it don’t attract my attention.” And he scuffed back to his desk, sat down and resumed his reading.

And that’s the way it went most of the year. We’d roll into physics class and spend the hour socializing, punching each other in the shoulder, tugging at the knot on Mary Helen Dumont’s wrap-around skirt, and tossing wads of rubbish and dusty erasers about the room. Once a week Mr. Clingfield would deliver a stack of tests to the classroom door, and Beaner would promptly drop them in the trash can. Of course, none of us studied any physics — the text books had not been passed out — but at the end of each six weeks, in strict accordance with school policy, Beaner would distribute our grade reports. I don’t know what he gave the other students, but no one complained — whether out of fear or satisfaction, I never knew — but I made my parents proud by bringing home straight A’s in physics.

I admit to having suffered maybe just a twinge of guilt. I had a sincere dislike for science courses and I hated numbers, preferring instead to read Civil War books by Bruce Catton. But once, on a rainy afternoon in November when I was feeling particularly self-righteous, I happened to mention “the Beaner situation” to a classmate, Eddie Jenkins. Eddie, a frail studious bespectacled boy who feared and worshiped Beaner, instantly informed me that was none of his business, that it was out of his hands, and that to open his mouth meant certain death. Eddie’s reasoning made perfect sense to me — and to any of Mr. Clingfield’s students who were capable of thought. So before we knew it, fall was a memory, winter had drifted into spring, and we were headed into the home stretch, Einsteins every one of us.

Then something happened. It had to. PSSC physics was simply too good to be true. But it was not a disgruntled parent or a rowdy student who gave us away; it was Mr. Clingfield. Just to pass him in the crowded hall that spring was to risk intoxication. His gait was irregular, his appearance scruffy. And so the inevitable: one afternoon during a particularly intense eraser battle, the classroom door banged open and there stood Principal Hanson.

“Where is Mr. Clingfield?” he asked as soon as the commotion had trailed off into a dazed silence. No one answered. He scanned the room. We stared back unflinchingly, too astonished by this intrusion to avert our eyes. Then he turned and pulled the door shut behind him. We bolted for our desks and sat waiting in silence. Through all this Beaner continued his reading. A minute or two passed. Then he closed the book and strolled to the front of the room.

“Here it is,” he said, leaning against the blackboard with the palms of his hands resting on the chalk rail. “You don’t know nothing about nothing. Clingfield has been here teaching all year and he just stepped out of the room for a few minutes today. Does everyone understand this?” Arching slightly forward, he looked deep into our souls. “Good,” he said. And he walked back to his desk, picked up his copy of Aesthetic: As Science of Expression and General Linguistics and resumed reading.

About ten minutes later, Mr. Clingfield entered the room. He looked haggard, distraught, bewildered — drunk. He went directly to his desk, sat down and buried his face in his hands. A moment later the door opened and Principal Hanson entered and stood glaring at Mr. Clingfield. He seemed about to reprimand Mr. Clingfield in front of the class — when Beaner raised his hand and asked, “In the problem we were discussing earlier, what would happen to the kinetic energy if we doubled the velocity?”

Mr. Clingfield didn’t move. Then he looked up and his bloodshot eyes brightened. “That’s a good question,” he said. “A very good question.” And he walked to the blackboard and began to scribble an equation. “Right here you can see it,” he said, breaking a piece of chalk against the board. “It would increase the kinetic energy by a factor of four.”

For a moment we held our collective breath and then even the thick-headed ones caught on. Notebooks flew open and we began copying the problem. Principal Hanson focused his attention on the equation, on Mr. Clingfield, on Beaner, then looked again at the class, this time with more confusion than anger, and walked out of the room, pulling the door shut solidly behind him.

Mr. Gingfield sighed and looked out at the classroom full of strangers. “Thank you” was all he said, and the bell rang.

The halls were immediately abuzz with the news of the discovery of Mr. Gingfield’s malfeasance and Beaner’s salvific intervention. As the day wore on the oft-repeated story acquired a new denouement.

Beaner Murphy, inveterate hater of all forms of authority, rescues from certain disgrace one of his sworn enemies. He asks a preposterously esoteric question of the teacher and the teacher, who is both drunk and stupid, muddles through with some implausible response. Then Beaner — enraged by the stupidity and hypocrisies of the adult world — cold cocks both Principal Hanson and Mr. Clingfield and is pursued for two hours through the catacombs of the school. Dogs are used to track him down and only after a fiercely violent struggle is he subdued — by no fewer than fifty policemen wielding nightsticks. Beaner finally yields to the overwhelming forces arrayed against him and is handcuffed and dragged off to the local lockup.

It was a great story, but to everyone’s disappointment, the pursuit/incarceration component of the narrative was proved false when Beaner was seen driving from the parking lot with his shiftless brother Dixon.

The following day promised to be the apogee of my high school career, and that night in bed I spent sleepless hours reviewing the infinite scenarios. I had known trouble in my life — all the routine adolescent traumas — and certainly the Clingfield escapade involved me. But not, I felt confident, to the extent that I’d experience any long-term ill effects. Certainly Mr. Clingfield would suffer, and maybe Beaner would feel the wrath of authority. But I was safe, an innocent bystander, the hapless victim of forces beyond my control.

But when I walked into class the next day, I was crestfallen. Instead of an angry principal or a contrite Mr. Clingfield, there was a substitute teacher, an assistant football coach, a well-known cretin of gargantuan physical proportions who was said to tolerate no foolishness. He explained in his native but halting English that Mr. Clingfield was sick and would return the following day. “You can use this time, you know, to study some of that stuff you got to study for, or whatever it is you need to do without making no noise.”

I looked over at Beaner. He sat slumped passively at his desk, the collar on his black leatherjacket turned up, reading in a book entitled Paint the Wind. Suddenly, he looked directly into my eyes. “Feeling cheated?” he asked.

Those remain the only unsolicited words Beaner Murphy ever spoke to me.

Mr. Gingfield did return the next day, but he sat quietly at his desk, reading the newspaper. Near the end of the period, he stood timorously before the class and apologized for not having taught us physics and explained that he had “certain physical problems” that prevented him from lecturing for “prolonged periods of time.” He thanked us for having put up a good show for Principal Hanson, but noted that his job — and his retirement — were in jeopardy unless we could somehow prove to the administration that our class — the class that he had neglected to teach — had been of value to us, his students. He reminded us that the annual science fair would be held in two weeks and suggested that we might redeem ourselves by making an impressive showing. “I would like to help each of you make the best science project this high school has ever seen. And I know we can do it,” he said. “I’m placing Mr. Murphy in charge of organizing our projects. When you have a plan, submit it to him.” And he walked unsteadily to his desk. “I’m asking for your help,” he added, his voice wobbling an octave on the words “your help.”

The science fair was The Big Deal of the school year. The objective of this exercise was to convince “the leaders of the Twenty-First Century” (an expression employed with irritating frequency by Principal Hanson) that they were capable of saving America from the imminent nuclear nightmare. Local political luminaries and the ministers from various reactionary churches were, for reasons which defy explanation, preferred as judges. They would appear at the school gym on the appointed day and meander among the erupting volcanoes, tin-foil sun furnaces, phototropic geraniums, maze-sniffing rats, electro-stimulated cacti, etc., and scribble copious notes with respect to the project’s level of inanity.

The majority of science students participated willingly in this exercise. It made no difference that they were one day destined to sell insurance or own pornographic bookstores or step on land mines in Asia; they poured their time and energy, their very souls, into producing scientific wonders no one would remember.

What patsies we were. I suspect we were simply too well brought up to do anything other than what we were told. And so we threw ourselves body and soul into contriving scientific wonders that would save our alcoholic teacher’s reputation. Students stumbled into class toting stacks of library books and spent hours leafing through the pages, making notes and chewing thoughtfully on the ends of their pencils. I came up with a scheme for a reenactment of the battle between the Monitor and the Merrimack. I wrote out my plan for baking soda propelled wooden models and submitted it in writing to Beaner. He glanced at my submission for two seconds and scribbled a definitive “good” on the first page. And that night I set about carving the ironclads out of blocks of wood.

As always, none of us had any idea what was going on in Beaner’s head. Was he inclined to ignore Mr. Clingfield’s supplications? Or did he intend to produce a science project of such magnificence, such startling originality and insight as to not only save our physics teacher from certain dismissal but to win him the Bayside Excellence in Teaching Award? Had his sad life with an alcoholic mother stirred within him some heretofore unknown modicum of compassion? Or did Beaner plan to even the score with a world that had treated him so shabbily?

Despite the fact that we knew nothing about physics, the proposed projects were rather inventive. Mary Helen Dumont planned a display in which the various brands of toothpaste were tested for abrasiveness. Itsey McGarby eviscerated flashlight batteries, exposing their innards and explaining with arrows cut from poster board the functions of the internal ingredients. Eddie Jenkins, whose father was an engineer for the highway department, wrote a lengthy explanation of periodic motion and transverse and longitudinal waves, though he admitted to me that he did not understand the project and was having difficulty constructing a device that would produce waves of adequate size and duration.

The opening of the science fair was scheduled for a Saturday, and on the preceding Friday we were sent to the gym to ready our display booths. Fifty or so cafeteria tables were arranged in a large rectangle, and we erected tall cardboard dividers meant to separate the projects. The plan was for each student to set up his display on Saturday morning and to have it ready for judging by early afternoon.

On the designated morning, Mother dropped me at the gym with a bag lunch and a caution not to lose her sauce pan, and I wandered inside to find the place writhing with activity. I began assembling my project at 10:00 a.m. and by 10:03 it was in operation. The Monitor, the sleeker and lighter of the two models, zipped across the pan of water with surprising alacrity. The Merrimack, on the other hand, listed conspicuously to port and bubbled in a sluggish circle. In front of the pan, I placed a sign I had carefully lettered the night before identifying the Civil War ironclads.

There were immediate difficulties, most notably the life span of the baking soda propellant. When replenished with fresh fuel, the models maneuvered well for two or three minutes, bobbing into each other and the sides of the pan. But then the baking soda began to lose its effervescence and the ships’ motion gradually diminished, coming to a complete yet historically accurate stalemate in the murky water. The first student to observe my project, a pimply ninth-grader, asked simply, “What’s that got to do with science?” The question startled me. “Well,” I said, “you know, the Monitor and the Merrimack.” Thus demoralized, I spent the remainder of the morning helping Eddie Jenkins perfect his wave machine, which was more scientific than my project but, I thought, less entertaining. About noon, Eddie asked, “When’s Beaner going to show up?” That was, of course, the question on every student’s mind.

I had just finished my peanut butter and jelly sandwich when I spotted Beaner in the lobby of the gym. I looked at my watch. It was one o’clock, the time designated for the judging. Beaner pushed open the glass door and scuffed in. He was wearing jeans and his black leatherjacket and was carrying a folded sheet and a shoe box under his arm. He walked past the other projects without so much as a glance and spread the sheet over the cardboard walls of his display booth, which was immediately adjacent to Eddie Jenkins’, and disappeared inside.

At that moment the judges entered the gym. There were only two: the Honorable Leroy Dunn, the town mayor, and the Reverend Calvin “Brent” Hackney of the First Baptist Church of Jesus Christ Our Lord and Savior. They carried clipboards and pencils and were accompanied by Principal Hanson and our wayward teacher, Mr. Clingfield.

The assemblage moved slowly about the gym, pausing in front of each science project, the judges making elaborate notations on their clipboards and occasionally gasping, “That’s just amazing.” With the judging of each project, the number of on-lookers increased until Principal Hanson was forced to hold up his hands and shout, “Would you all please stand back so that the judges can have some breathing room?”

By the time the judges had reached my booth, there were about two hundred people crowding and elbowing against Principal Hanson’s outspread arms. I had managed to refuel the Monitor and the Merrimack just moments before the throng sidestepped in my direction, and my model ironclads were bubbling about crazily. The judges stared at my explanatory sign and looked at each other. Then Mr. Clingfield came to my rescue. “Ah,” he said, “for every action there is an opposite and equal reaction.” The judges smiled, scribbled a word or two on their clipboards and moved on to Eddie Jenkins’ wave display.

I eased around the perimeter of the crowd and took up position directly in front of Beaner’s booth. He was leaning casually against the table with his thumbs hooked in the belt loops. He stared at me, but he didn’t speak. The sheet was now spread over his project, which struck me as lacking the dimension, the necessary bulk, that was a sure indication of scientific excellence. Just then the judges, Principal Hanson, Mr. Clingfield and the crowd jostled in beside me. Someone whispered, “Is that the kid who made the bomb?” Then the shoving stopped and there was silence.

“This is the project I’ve been telling you about,” said Mr. Clingfield, his hand flailing forth with a dramatic flourish. “Mr. Murphy here is among the best physics students I’ve had the honor to teach in the last twenty-nine years.”

The judges looked at one another and smiled. Principal Hanson just stared. Beaner didn’t move.

“Well,” said Principal Hanson, “would you mind showing us your project?”

Face expressionless, body relaxed, Beaner reached over and with the aplomb of a magician he instantaneously lifted the sheet.

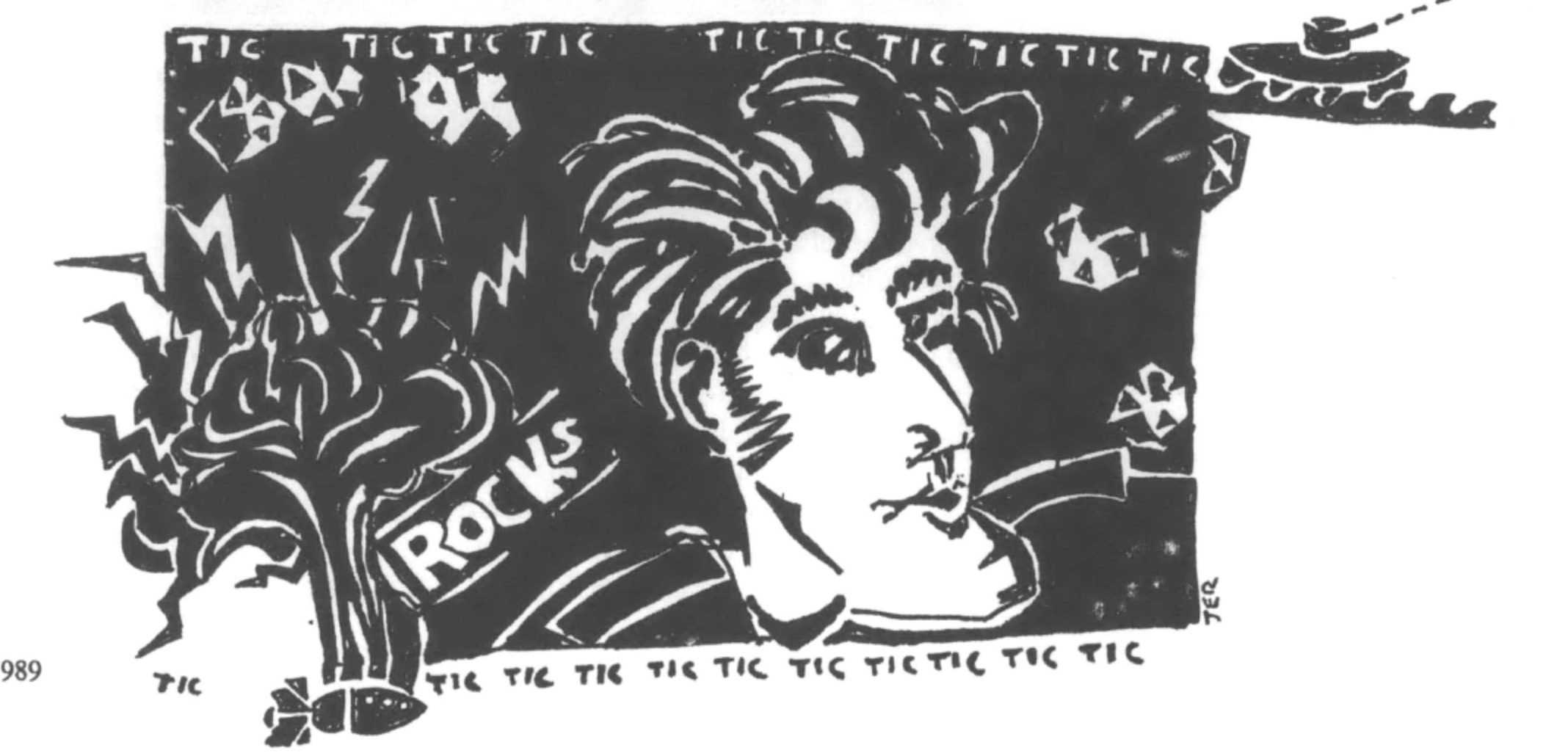

On the bare formica table sat a standard, brown cardboard shoe box. Inside the box were rocks of the type one might find in the driveway of an expensive home — smooth, cream-colored rocks somewhat uniform in size and shape. But nothing else. And in front of the shoe box was a sign with just one word scrawled in magic marker: ROCKS.

The box was full of rocks.

Mr. Clingfield’s eyes rolled back in his head. The judges stared.

“Would you mind explaining this?” asked Principal Hanson.

Beaner ran his eyes along the crowd. “Speaks for itself,” he said.

What in the world did Beaner intend? What was the point? Rocks? What was he thinking? A shoe box full of rocks? Rocks in a shoe box? I looked around at the other projects, then at the bewildered faces of the crowd, and finally up at the high steel-beamed ceiling of the gym. And suddenly it came to me. Couldn’t they see? Didn’t they get it? Amidst all this ostentatious nonsense, this haphazard detritus, here was a moment of perfect simplicity! Rocks! Just rocks! I startled myself by laughing out loud. There followed a few muffled coughs and the clearing of two or three throats. Someone moaned, someone else sighed. But no one spoke until Principal Hanson said, “I believe that it’s time we moved along.” Then looking at Mr. Clingfield he spoke in a voice loud enough for everyone to hear, “We’ll discuss this after the judging.” And the mob shuffled off to the next project, leaving me staring into Beaner’s icy blue eyes.

“They didn’t understand,” I said. “They didn’t get it.”

“I told you once,” Beaner said, “get your ass out of my business.” And he walked out of the gym and out of our lives forever.

The following Monday no one mentioned Beaner’s science project. It was as if his classmates had suffered profound disillusionment. They sat at their desks silently, introspectively. Perhaps they were perplexed by Beaner’s project. Probably they were just disappointed. But Beaner’s name went unspoken for the remainder of the school year.

Mr. Clingfield was allowed to stay on through June and take his full retirement, though he sat in front of the class for days suffering with what I believe was a full-blown case of the DTs. During the final exam period, we were required by Principal Hanson to take a multiple-choice PSSC exam. I didn’t know the answer to even one of the questions, so I just filled in the blanks using the rhyme scheme for a Shakespearean sonnet, excluding the “g g” of the concluding couplet. Mr. Gingfield graded the exams; I received an A.

As for Beaner, he never returned to school, and a year later he and his brother were arrested for robbing an all-night gas station. According to an article in the Star-Democrat, Beaner beat the attendant unconscious. The next day he and his brother were apprehended by the police. Beaner got ten years.

For a long time after my graduation, I was content with the easy explanation: Beaner had simply been getting even with us — the small town that had shunned him, the teacher who had punished him that first day of school, his classmates, Mr. Clingfield, the father who’d abandoned him, all the lunchmeats of the world. Perhaps he believed he had sent us all to the cloakroom for the rest of our lives. During the late sixties, I supposed that Beaner’s science project was one big existential raspberry, a definitive statement on the insanity of it all. Since then I’ve had other theories, varied as the temperament of the times that engendered them.

A few years ago we held our twenty-fifth class reunion. Old Bayside High School had been renovated for use as a community arts center, and the dinner-dance was held in the old gymnasium, site of the annual science fair. Beaner, of course, was not present, but folks kept asking about him. Mary Helen Dumont said that she had heard from someone who had heard from someone that he was a millionaire real estate broker in Florida. Itsey McGarby claimed that he’d read that Beaner had died in a motorcycle accident in the early seventies. Near the end of the evening, Eddie Jenkins, still bespectacled, still lunchmeat, turned to me. “You know,” he said, “I often think of Beaner and that science project of his. I don’t know why, but I wish he was here.”

“Feeling cheated?” I asked.

Tags

Stephen E. Smith

Stephen Smith teaches at Sandhills Community College in Southern Pines, North Carolina and writes country songs. His most recent book is The Honeysuckle Shower from St. Andrews Press. (1989)