This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 3, "Inside Looking Out." Find more from that issue here.

These days the buzzword in Louisiana is “diversification.” The ultimate goal of most discussions on the subject is to figure out how to get around the carcass of big oil, which is sprawled across the road to the future. True to our state’s track record, the first thought on everybody’s mind seems to be “Let’s throw a party.” Well over 100 fairs and festivals are held each year in southern Louisiana alone. This is lots of fun, but unfortunately not very lucrative in the long run and not even always such a good idea. The 1984 New Orleans World’s Fair, for example, not only lost big money, but almost strangled the cultural life out of the city for a very simple reason: It stayed open until ten o’clock. Tourists saw and heard and tasted everything they wanted on the fair site and didn’t need or want to visit any museums, nightclubs, or restaurants. There is already an abundance of festivals in Louisiana. I wonder if creating a bunch of new ones is really going to give us the new shot in the arm we all want and need. After all, festivals come and go and when they come, they are a mess, and when they go, they’re gone.

Tourism is hot on the list of prospects for diversification because tourists don’t just recycle old dollars, they bring in new ones, just like oil companies used to do. A good idea, but not as easy as it seems at first glance. Tourists come to a place because they feel there is something worth seeing, hearing, tasting, and doing there, something they can’t do at home. Why else would they bother leaving? Now, there’s lots of that sort of thing where I live in south Louisiana. Cajun cooking, Cajun music, Cajun French, Cajuns, swamps, alligators, and so on. The trouble is how to get to it. Visiting south Louisiana is like a safari. There aren’t many orientation points for visitors, so they have to make their own way most of the time. Consequently they often leave the area feeling frustrated and disappointed because they didn’t see what they wanted to see or hear what they wanted to hear. Or they end up visiting us in our living rooms, which is just as bad.

We don’t have the proper conduits to handle the primary flow of casual visitors who want only a brief brush with the Cajun experience, so they end up in real places. When a whole busload of tourists arrives at one of the area’s dance halls, for example, regulars are pushed to the walls. Their weekly renewal ritual of Saturday night dancing is disturbed to serve the passing interest of the tourists. Next Saturday night, the tourists are gone, but things are not quite the same. It might take weeks before die dance hall owner gets over his new idea of a successful night, based on the extra business the gang of tourists brought, and before some of the shyer regulars feel it safe to return to their cultural haven. The soaring prices in restaurants and the proliferation of water skiers and alligator sight-seeing tour boats in the Atchafalaya Swamp Basin are further evidence of the uncomfortable changes brought about when tourists are allowed to visit real places unchecked.

But there is a solution. What we need is a conduit. The American Indians have understood the concept of conduits for years and are quite serious about the business of protecting real tribal life from the standard tourist. Many tribes run visitors through a “reservation” where they can meet “authentic” (which, in current usage, has come to mean “authentic-like”) Indians, see “authentic” dances and, especially, buy “authentic” tribal crafts. And a few miles down the road, they have a real village, financed by the tourist trade, where their traditional life remains largely undisturbed. Both sides are happy because both get what they want from each other. This kind of setup could serve as a model to present and preserve our own real Cajun folklife. One alternative which looms large on the horizon, whether we like it or not, is CajunLand, a full-blown theme park that someone is going to get the idea to develop someday, probably somewhere near the corner of Interstate 10 and Interstate 49.

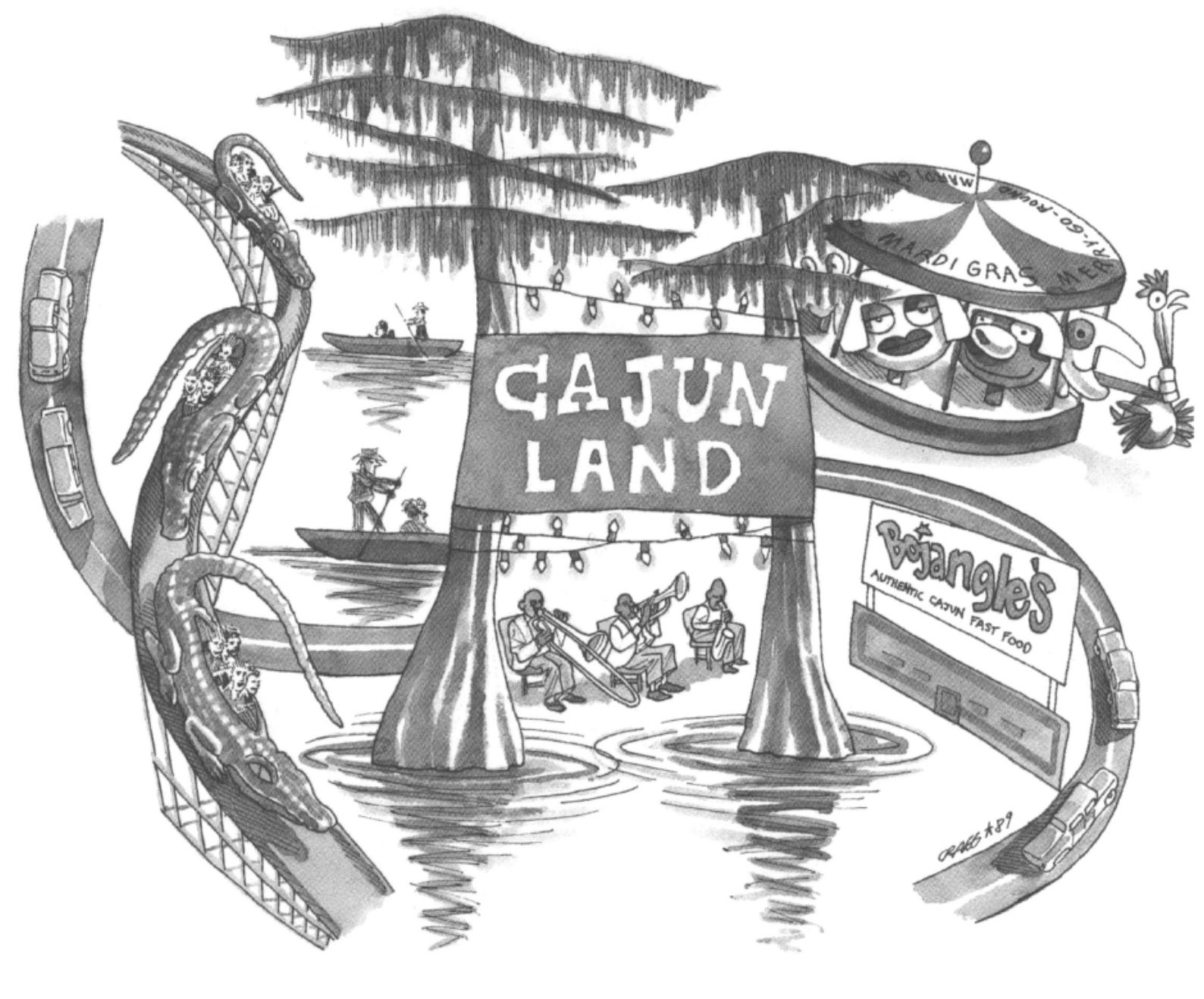

Before dismissing this alternative as crass commercialism, let’s consider the possibilities for a moment. A slick theme park could give some visitors most of what they think they came for and get them back on the road before they know it. It could have alligator and pirogue rides through a reconstructed swampland environment. It could serve either Popeye’s or Bojangle’s Cajun Fried Chicken and Pizza Hut’s New Orleans-style Cajun pizza. Visitors could wash it all down with the new cayenne-laced Cajun Beer (conceived and brewed in Milwaukee). Nashville-based Cajun fiddler Doug Kershaw could be in charge of musical shows, and self-described “half bleed” Cajun comedian Justin Wilson could be honorary mayor. Workers could run around barefoot, dressed like Evangelines and Gabriels, and speak broken English while demonstrating just exactly how to let the good times roll. Souvenirs could include “coonass” T-shirts and Crawgator mugs. For smaller children, the park could have rides like the Mardi Gras Merry-Go-Round, which would feature a chicken, instead of a brass ring, to catch. For older kids, it could have rides with names like “Top of the Derrick,” “The Crawfish Hold,” and “Le Grand Boudin” (which would squeeze riders out of a giant sausage tube and back into their cars). And best of all, there would be easy-off/easy-back- on access to the interstate. There could even be a drive-through feature. Think about it; the possibilities are endless. Why, I might even do it myself if I could keep my tongue out of my cheek long enough to present the idea to the right backers.

But there are more palatable and serious alternatives to this type of abuse and self-exploitation, alternatives that include carefully planned visitor’s contact points. For example, in my hometown of Lafayette, local government is joining forces with private industry to develop the Bayou Vermilion project, which would clean up the bayou and develop its potential for recreation and tourism. The ecological importance of preserving the bayou is admirable enough. But there is also a proposal to build a cultural and historical interpretive center called “Vermilionville” and to organize forays into the swamps and bayous of the area.

If projects like these were done wrong, we could end up with a cheap imitation of Cajun culture, like CajunLand. In the Bayou Vermilion projects, however, organizers have the opportunity to work in cooperation with Louisiana’s new Jean Lafitte National Park to build an appropriate and elegant statement based on sound research. By carefully preparing these facilities and activities, we could finally have a place where tourists could be sure to get the story they came for, and we could be sure that tourists are getting the right story about where the Cajuns come from and why we are the way we are, going beyond typical media stereotypes of the Cajuns as barefoot, belligerent, swamp-dwelling drunks. Tourists would leave their dollars with us and take with them accurate information about the Cajuns to balance the scales next time they see Cajun culture slandered in a film, television documentary, or magazine article.

Tags

Barry Jean Ancelet

Barry Jean Ancelet is a folklorist at the University of Southwestern Louisiana in Lafayette. (1991)