Over Committed

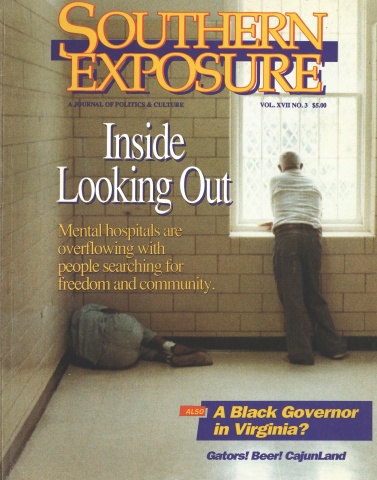

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 3, "Inside Looking Out." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Charleston, S.C. — When Donna Blixen took her neighbor’s car out for a spin two years ago, she thought she had permission from God.

Her neighbor thought otherwise. When Blixen returned, the police were waiting. They slapped handcuffs on her, put her in the back of a patrol car, and carted her off to jail to await psychiatric evaluation.

Blixen, a 60-year-old retired nurse, remembers an officer at the jail telling her, “We gonna kill you.” She says that her cellmates called her names and beat her repeatedly.

After two days in jail, Blixen was committed to a state mental hospital. She was held for a week before being diagnosed as manic-depressive, given a prescription for stabilizing drugs, and released.

Those nine days left Blixen shattered. Today she discusses her experience with few people. She is afraid to leave her home, and she fears the police even more. “Her self-esteem is gone,” says the leader of her mental health support group, who asked that Blixen’s real name not be used. “Nowadays she’s talking about suicide.”

What happened to Donna Blixen underscores the physical and emotional violence that can accompany admission to state mental hospitals. Last year Southerners were committed to 72 state-run psychiatric hospitals against their will more than 86,000 times. Most were locked up with only a cursory psychiatric evaluation, then forced to wait days or even weeks for a public hearing.

Many Southern states have few legal safeguards to protect anyone from being involuntarily committed to a mental hospital. In South Carolina, for example, citizens can be held for three weeks with no chance to contest their confinement. All it takes is two signatures — neither of which need to be from someone experienced in mental health care.

Such wide-ranging powers have given states tremendous control over whom they label “crazy” and commit to hospitals, resulting in widespread discrimination. Information gathered from the National Institute of Mental Health and state mental health departments reveals that race plays a primary role in determining who gets committed to mental hospitals against their will, where they are sent, and how they are treated.

Taken together, the numbers indicate that states are using their authority to lock people up in mental hospitals as a powerful form of social control, creating a system of racial segregation.

“If you want to control people, what better way than to use the disability system?” says Curtis Decker, executive director of the National Association of Protection and Advocacy Services. “The system meets the needs of racial segregation . . . by sending people away to secluded places in the country. We have a history of putting people we don’t like away from us.”

Black and White

Our survey of nine Southern states that provided admissions data by race reveals a mental health population sharply divided according to their skin color. Some of the findings:

♦ A disproportionate number of people involuntarily committed to state-run mental hospitals last year were black. Overall, blacks were 2.7 times as likely as whites to be committed without their consent. Although Florida hospitalized people at the lowest rate of any state, it discriminated the most on the basis of race, committing blacks at a rate nearly five times greater than that for whites.

♦ Nearly 37 percent of those committed against their will were black — even though blacks represent only 19 percent of the population of the surveyed states. The widest disparity again occurred in Florida, where blacks comprise 14 percent of the state population but make up 35 percent of involuntary commitments.

♦ Three of the blackest and poorest states in the nation — Mississippi, South Carolina, and Alabama — have the loosest commitment laws, allowing citizens to be confined to mental hospitals indefinitely, without judicial review.

♦ Economics and the unbalanced commitment process create public and private psychiatric hospitals that are divided along racial lines. Blacks accounted for 34 percent of all residents at state mental hospitals in the South in 1986, but only 13 percent of residents at private psychiatric facilities. Based on state populations, blacks were overrepresented in public hospitals and underrepresented in private facilities in every Southern state except Virginia and Arkansas.

♦ Black patients were consistently diagnosed with more severe mental illnesses than whites, subjecting them to heavier doses of drugs and longer hospital stays. In South Carolina, for example, a third of all blacks were diagnosed with schizophrenia, a figure three times that of whites.

National studies indicate that this pattern of discrimination is not confined to the South. According to a 1980 survey of selected psychiatric hospitals by the National Institute of Mental Health, blacks were 2.8 times as likely as whites to be involuntarily committed to mental hospitals.

“The problems faced by black and Hispanic and other minority mental health consumers are serious and widespread,” concludes a report released last year by the Mental Health Law Project, a non-profit research group in Washington, D.C. “It is a fact of their everyday life that black and Hispanic consumers are underserved, misdiagnosed, segregated, and overinstitutionalized.”

Out of shame or sloppiness, most states try to keep their discrimination a secret. No Southern state keeps a count of the number of blacks they commit to mental hospitals each year, many of the figures in our survey had to be compiled on a hospital-by-hospital basis. Hospitals in four states — Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, and West Virginia — refused to provide any racial breakdown of their admissions.

“We’re never asked to break them down that way,” said Janet Jenkins, director of admissions at Central State Hospital in Louisville, Kentucky. “We break them down by sex, but not by race. We just haven’t experienced any demand for that information.”

The figures obtained for involuntary commitments tell only part of the story. Southerners also willingly signed themselves into state mental hospitals 27,000

times last year — often only after being arrested or pressured by their families and officials.

Ken Thomas, a former patient at state mental hospitals in Kentucky, says officials routinely “coerce” people into signing “voluntary” admissions forms by telling them, “If you sign that paper we’ll keep you for three weeks, and if you don’t, we’ll keep you for three months.”

With the number of voluntary admissions to state hospitals declining in many states, the racial disparities appear to be worsening. In both Texas and North Carolina, the only two states with consistent records, the number of black patients remained relatively steady between 1975 and 1985 while the number of white patients plunged — by 21 percent in Texas and 53 percent in North Carolina.

“Unfair to Everybody”

The primary reason blacks are committed to mental hospitals more frequently than whites is that they are easy targets for an arbitrary commitment system — a system the U.S. Supreme Court has condemned as a “massive curtailment of liberty.”

Patients like Donna Blixen who have been arrested and committed call the process “dehumanizing” and “nightmarish.” Kay Omholt, a former patient who now works as an advocate for the mentally ill in Arkansas, said being threatened with involuntary commitment “was the worst experience of my life.”

Although our survey counted anyone locked in state-run psychiatric hospitals against their will — including mentally ill citizens awaiting trial, mentally retarded adults, and substance abusers — most of the involuntary admissions involved people who have committed no crime. The legal protection they receive varies from state to state, but many have few ways to escape when faced with imprisonment in a mental hospital.

In every state, anyone — even a total stranger — can sign a petition asking officials to commit you to a mental hospital. You would then be examined by a doctor to determine if you are mentally ill and represent “a danger to yourself or others.” Only Virginia and West Virginia require that the examining physician have experience in diagnosing the mentally ill.

If the doctor agrees to commit you, you could be held in a mental hospital for anywhere between three days and three weeks before being given a chance to contest your incarceration. During that time you could legally be restrained, locked in an isolation cell, or given mood-altering drugs without your consent.

A full commitment hearing is usually held before a probate judge, although Louisiana allows local coroners to have the final say in committing people to mental hospitals. The maximum legal length of commitment ranges from 45 days in Arkansas to unlimited terms in Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina — the only three states in the nation which allow citizens to be locked in mental hospitals for life without any periodic review.

“It seems to me that the system is unfair to everybody,” says Laveme Bonner, an advocate for the mentally ill in South Carolina. “The system is unfair — period.”

Bonner’s state is especially unfair. Under South Carolina law, all it takes to commit someone to a state hospital for 20 days is two signatures. No other state allows citizens to be detained for longer than 10 days without a hearing to determine “probable cause” for commitment.

Even when a citizen finally receives a hearing, it’s who you know that counts. South Carolina Probate Judge Bernard Fielding told the Greenville News, for example, that a fellow judge committed a man who had not yet arrived for his hearing.

“It seemed that the doctor was in a hurry,” Judge Fielding said, “and in order to accommodate the doctor, he went ahead with the trial and said the hell with the patient.” When the client arrived in court, the judge sent him away, saying he had “already tried him.”

Public vs. Private

The commitment system hits the poor the hardest because they lack the money to hire lawyers to defend themselves. Deborah Whisnanet, a Florida attorney who serves as an advocate for the mentally ill, compares commitment hearings to trials. “When you go to the hearing, the person who has the most resources is most likely to win,” she says.

In many cases, those “resources” are enough to keep affluent patients out of state hospitals. In West Virginia, a relative or friend can step forward during a commitment hearing and volunteer to take care of the person being committed. “Blacks may not be able to pay for something like that,” notes one West Virginia advocate.

The lack of resources available to low-income blacks results in increasingly segregated public and private psychiatric hospitals. While the poor can get federal and state aid to help pay for care in state mental hospitals, they usually have no health insurance and cannot afford private care. Residency in private mental facilities often runs as high as $13,000 a month.

“Private hospitals certainly only serve a certain segment of the population,” said Deborah Whisnanet.

As a result, whites make up a much higher percentage of residents in private psychiatric facilities than at state mental hospitals. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, 83 percent of residents at private Southern hospitals in 1986 were white, compared to 63 percent at public hospitals in the region.

The figures also show that West Virginia and Kentucky — the whitest states in the South — have the greatest disproportion of black residents in state mental hospitals. According to the figures, three percent of all West Virginians are black, compared to 14 percent of all patients in state mental hospitals. Blacks in Ken-

tucky make up seven percent of the population outside state hospitals, but 20 percent on the inside.

The shortage of community mental health services in most states also condemns the poor to second-class care at large state institutions. Community-based mental health centers are supposed to provide more individual treatment and counseling than understaffed hospitals, which tend to rely on drugs to keep patients restrained.

Yet studies indicate that even when mental health services are available in black communities, they often fall short of the care provided in white neighborhoods. “Like other scarce public resources,” says the Mental Health Law Project, “mental health centers tend to be even less adequate in low-income communities.”

Schizophrenia and Shoe Polish

Race not only plays a central role in who gets committed against their will and where they are sent, it also shapes how patients are treated — and mistreated — once they enter the mental health system.

According to 1986 figures from the National Institute of Mental Health, psychiatrists tend to diagnose minorities with more severe mental illnesses than whites. Black men in both public and private mental hospitals, for example, were diagnosed as having schizophrenia — one of the most severe mental illnesses — at almost twice the rate of whites.

The disparity is even greater for black women. A 1981 study published in Professional Psychology revealed that schizophrenia ranked last as a diagnosis for white women admitted to psychiatric care, but it was the leading diagnosis in the admission of black women.

The numbers mean that black patients are likely to be locked up longer — and drugged more heavily — than their white counterparts. ‘The diagnostic pattern makes hospitalization both more likely and more dangerous,” reports the Mental Health Law Project, “because schizophrenia carries with it a poor prognosis and a greater expectation of chronicity. Further, misdiagnosis leads to mistreatment.”

Behind the numbers, mentally ill citizens and their advocates tell stories of how racial bias permeates the mental health system. State mental hospitals with black populations of over 40 percent often have few or no black psychiatrists or social workers on staff. The result: Low-income black patients are usually diagnosed and treated by middle-class white professionals who know little about their language and culture.

Laveme Bonner, the South Carolina advocate, cites the case of a black woman who was interviewed by a white psychiatrist for admission to a state hospital. When asked if she had attended college, the woman replied that she had. The doctor wrote in her records that the patient was exhibiting signs of “grandiose ideation.”

Bonner says the woman later produced proof of her degree, but the doctors were still skeptical. “When she showed them her transcripts, they said, ‘Maybe.’”

Frank Chaney, a black patient at Florida State Hospital in Chattahoochee, tells similar stories of discrimination. He says he has been called “nigger” and “boy” by hospital staff, and has asked repeatedly to speak to a black psychiatrist. When he put the request to his current psychiatrist, he says, the doctor was eager to comply.

“He said, ‘I’ll put some black shoe polish on my face and we’ll sit down and talk,’” Chaney recalls.

Faye Alcorn, assistant administrator at Florida State, says she knows of no such incident. “I hope that wouldn’t occur here,” she says. “That’s not something we would approve of.”

Alcorn acknowledges that none of the 52 psychiatrists at the hospital is black, even though four out of every 10 patients are. “I wouldn’t say that not having any black psychiatrists hurts the black clients,” she says.

Such cases of outright prejudice and cultural insensitivity also extend to poor whites. Bill Stewart, director of the Kentucky protection and advocacy system, says he knows of psychiatrists who have used the Appalachian expression “I don’t care” — which often means “yes” or “sure” — as evidence of mental illness.

Danger in the Law

Despite evidence that most states use commitment laws to segregate mental hospitals, advocates for the mentally ill say there is a move on to make it easier for states to commit people involuntarily. “I see a strong, national movement to loosen commitment laws,” Stewart says.

In state after state, the battle over commitment laws is pitting the mentally ill against members of their own families. The Alliance for the Mentally Ill (AMI), a national organization for families of the mentally ill, has pressed for broader laws that often give states greater freedom in deciding who will be committed to mental hospitals.

Many of the legislative Fights center on slight changes in wording that can dramatically alter the criteria for commitment Most states require that the person being committed be shown to present “a danger to himself or others,” and a few even require that the threat be evidenced by some “overt act” — but family members and patients often disagree about what constitutes a danger.

“Family groups and patient groups have different interests,” says David Marshall, a former mental patient who serves as an advocate for the mentally ill in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. “A big problem is what ‘overt act’ means. It depends on what county you’re in.”

Marshall called one recent bill “literally the worst commitment procedure I’ve ever seen. Anyone with arrest power could detain people for observation.” Advocates rallied against the measure, and the bill was killed in committee.

In North Carolina last year, AMI members convinced the state to pass an “emergency commitment” law allowing them to bypass the court and have family members committed by a psychiatrist or psychologist. “I know of a number of cases where, for families, that has been a real godsend, because they have not had to go that extra step,” said John Baggett, state director of AMI.

Baggett acknowledged some people committed under the new law have been freed by a judge who ruled they were committed improperly. He emphasized, however, that AMI “does not want to undo the due process aspects of commitment procedure. We would like to make commitments less traumatic for everyone.”

Without significant civil rights protections for those threatened with involuntary commitment, however, states will continue to have wide discretion in labeling people “dangerous” and sending them away to mental hospitals. Most changes in state commitment laws currently being discussed seem unlikely either to improve treatment for the mentally ill or to abolish the pattern of widespread discrimination.

Kay Omholt, an Arkansas advocate for the mentally ill, recently sat on a task force that argued “for hours and hours” about commitment laws, and eventually changed the wording substantially. The result? “The wording didn’t change anything,” Omholt says. “It’s still up to the judge’s subjective judgment.”

Tags

David Ramm

David Ramm conducted this investigation as an editorial assistant at the Institute for Southern Studies. He is currently a student at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. (1989)