This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 3, "Inside Looking Out." Find more from that issue here.

Roanoke, Va. — At Pine Ridge Home for Adults near Farmville, the new owner tangled with a mentally ill resident who refused to leave the kitchen. After the resident kicked him in the stomach, the owner pulled a gun and shot him.

At Arnold’s Rest Home near Abingdon, a woman diagnosed with schizophrenia suffered mysteriously broken legs, arms, and ribs. For several days, the only way she could get from her bedroom to the dining room was by dragging herself across the floor on her bottom.

At Hairston’s Home for Adults in Martinsville, the owners admitted a 26-year-old mentally ill man convicted of assaulting a resident at another adult home. A few weeks later, he was charged with murdering a 59-year-old resident by pushing him under scalding water.

At Cardinal Home for Adults in Botetourt County, a mentally ill resident threatened to commit suicide. The owner opened a medicine cabinet, showed him an unloaded gun, and said: “Go ahead.”

Thousands of mentally ill people are in danger of abuse and neglect in adult “board-and-care” homes across Virginia.

They are victims of a handful of untrained or greedy adult-home owners who try to squeeze maximum profits out of their businesses. They are victims of a weak-kneed welfare system that has largely failed to police these operations. And they are victims of a tight-fisted state government that has failed to come up with money to improve conditions in poorly run adult homes or find the mentally ill better places to live.

State officials have done little to change the flawed system — despite repeated critical studies and numerous horror stories over the past decade. Instead, officials have continued steering many of the state’s most vulnerable citizens into adult homes.

Homes for adults are not nursing homes. Although they care for 20,000 people — including an estimated 4,000 residents with mental illnesses — they generally have no full-time doctors or nurses on duty. They are supposed to provide the basics — room, board, and supervision — to adults who have been unable to live on their own.

State officials and adult-home owners insist that most of the 446 adult homes in Virginia are safe, clean and well run. “I would say 90 percent are doing a commendable job,” says Jo Ella John, president of the Virginia Association of Homes for Adults.

But a six-month investigation of adult homes in Virginia has uncovered widespread problems throughout the system:

♦ Most adult-home workers have no training in dealing with mentally ill residents. In many cases, the staff is underpaid and uneducated. At some homes, two or three untrained staffers are left to supervise dozens of seriously mentally ill residents.

♦ Adult-home owners can flout state welfare regulations for years. The only penalty the state has is to revoke a home’s license — an action welfare officials seldom try.

♦ Social workers and mental health agencies, understaffed and overburdened by growing case loads, often shunt the mentally ill from home to home with little regard for their needs.

♦ Thousands of mentally ill adults are stuck in large state institutions and adult homes because officials have failed to develop adequate housing and support services in local communities.

By steering people into adult homes, mental health advocates say, the state often exposes them to abuse and exploitation. Even well-run homes, they contend, do not offer the supervision and help the mentally ill need.

“To have four people jammed into a bedroom together, that’s not a way anybody would want to live,” said Karen Mallam, executive director of the Virginia Alliance for the Mentally Ill. “Why should our mentally disabled citizens be forced to live some way that other people wouldn’t want to live?”

Gretchen Stubbs, a mentally ill woman who lived at an adult home that was shut down for mistreating residents, put it more directly. “When you’re in an adult home,” she said, “you feel like you’re doomed until you die.”

“A Disgraceful Failure”

Virginia’s adult homes are part of a national problem that the late U.S. Representative Claude Pepper of Florida called “a tragedy of epic proportions and a disgraceful failure of public policy.” National studies this year uncovered widespread abuses at 68,000 board-and-care homes housing an estimated one million Americans.

The pattern of adult-home abuses is also a modern-day reminder of Virginia’s history of institutional horrors against the mentally ill — including beatings, shock therapy, and sterilization.

Adult homes were originally established as “old-folks homes” where the elderly could quietly live out their years. Two decades ago, the rest-home business was a mom-and-pop industry of mostly small homes averaging about two dozen beds each.

That changed in the 1970s when Virginia joined a national movement known as “deinstitutionalization” — clearing mentally ill adults out of state institutions. The goal was to help them live as normal lives as possible in local communities.

There was one flaw in the plan, however — there simply was and still is nowhere for many released patients to go. Often, they have no families, or their families cannot or do not want to care for them. Nearly as often, they are left with few choices, stripped of their privacy and dignity.

Instead of setting up publicly run group homes or apartment programs for released patients, the state placed many in adult homes — usually private, for-profit facilities designed for the elderly and unequipped to care for the mentally ill. Since then, the number of people living in adult homes has more than tripled, and the system has become a catch-all dumping ground for the state’s unwanted.

Today adult homes are a growing industry. Homes range in size from four to 600 residents, with an average of about 47. They care for a diverse population that includes the elderly, the retarded, and the mentally ill, and they have started competing with nursing homes for residents.

Many of the homes are supported at least in part by tax dollars. Adult homes receive up to $581 a month for each of the estimated 5,500 poor residents who rely on federal Supplemental Security Income and state auxiliary grants to pay for their keep.

Yet that tax money — between $30 million and $40 million a year — seldom results in well-staffed adult homes. The state requires no minimum staffing levels, and homes that rely on public assistance often pay minimum wage to most of their workers and offer no training in caring for the mentally ill.

“Keeping good help is just almost impossible,” says Jo Ella John, president of the adult-home association. “The pay is low and the work is difficult.”

State officials and adult-home owners concede that the most vulnerable of adults — the poorest and loneliest of the mentally ill — are often the ones most at risk in homes staffed by untrained workers.

“Morons and Wackos”

Samuel R. Keisler knew how to keep people in line at his home for adults in rural Gloucester County.

“I’m not talking about beating or anything,” Keisler said recently. “I’m talking about shaking them up a little bit.”

One mentally ill resident named Jack said Keisler beat him with a broomstick. Jack, 46, also said Keisler took him outside in the middle of winter and sprayed him with a water hose to teach him a lesson for spitting on himself.

Keisler admitted to officials that he yelled and cursed at Jack and made him stand in the corner for half an hour or more.

But he denied hitting him with a broomstick.

“It was a little bamboo stick, an Oriental backscratcher,” Keisler said. “Yeah, I whacked him some.”

Keisler also admitted he slapped Jack in the face. When a social worker asked why, Keisler said: “Because he pissed all over the living room furniture. A person can only take so much. I can only stand so much.”

Social workers run across scores of such cases of abuse and neglect at adult homes every year. In fact, a review of state inspection reports for more than 50 adult homes shows that such problems are not uncommon — and in some homes residents are abused or neglected for years without detection.

Keisler ran Abingdon Home for Adults for one and a half years before welfare officials discovered mistreatment and took away his license.

A licensing inspector said she found residents dirty and smelly and that Keisler had ordered male residents to urinate in the yard. Residents told the inspector that Keisler kept their welfare checks without giving them spending money required by the state.

Keisler called his residents “morons” and “wackos” in front of the inspector and another social worker. “He made fun of one of the resident’s haircut,” the inspector reported. “When we pointed out that this is unacceptable, he just laughed.”

Keisler accused mental health officials of using his home as a dumping ground for their most difficult clients. He said social workers were usually too busy to stop by — although they did give the Keislers some books on behavior modification to read.

Busy Breakfast

With state inspections infrequent and many residents too frightened or disoriented to complain, such abuse and neglect usually remain a well-kept secret. Nevertheless, complaints to local social workers have grown nearly fourfold since 1984, and state documents show that roughly 145 adult homes — one-third of the total — represent at least “moderate to serious” risks of abuse, neglect, or other problems.

State officials and adult-home operators say abuse and neglect often can be blamed on understaffing or on low-paid, poorly trained workers at the homes.

Each day, owners and aides in adult homes give out powerful medications to mentally ill people — yet few have the experience to notice when someone is being overdrugged. Atone home, the operator admitted he often changed the dosages of medications when residents became violent or began “acting a little funny.”

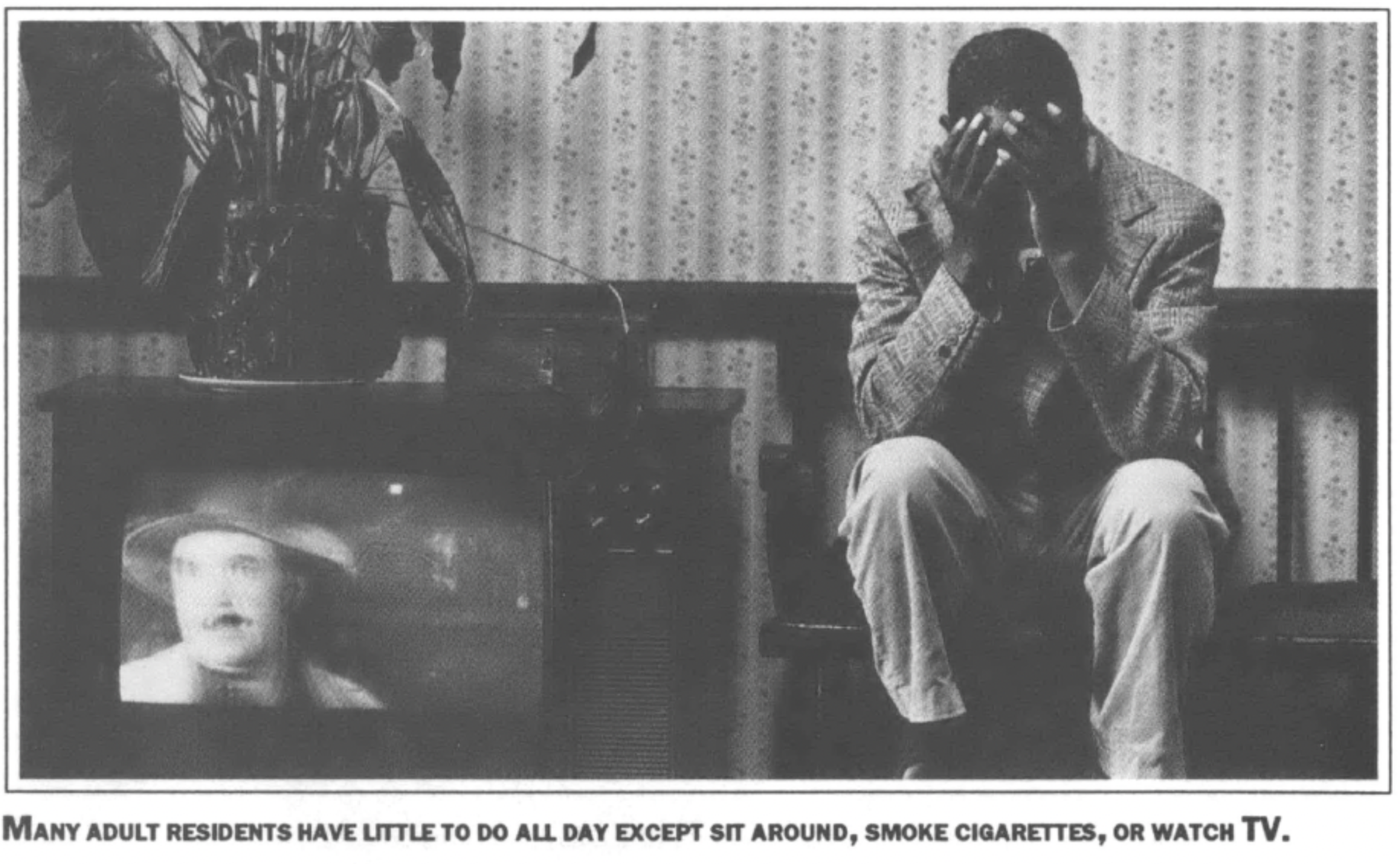

Because few homes have staffers who encourage mentally ill residents to be active, many residents spend most of their time sitting around doing nothing, smoking cigarettes or staring at TV game shows. And sometimes worse things happen.

On the last Sunday in January 1988, for example, Southern Manor Home for Adults in Roanoke had three “housekeeper/aides” on duty to supervise about 70 residents. One resident diagnosed with schizophrenia wandered away and jumped to his death off the Wasena Bridge.

An aide later testified that even though the man had been acting increasingly delusional, she didn’t know that she was supposed to stay with him and watch him. And, she added, she was too busy during breakfast time anyway.

At Commonwealth Health Center in Martinsville, inspectors found that at times just one staffer had been assigned to care for 51 residents on three floors. During 1987, an inspector found repeated evidence that the staff was neglecting residents:

♦ One resident had thick, yellow toenails that were so long they were curling into his skin.

♦ A man with infectious hepatitis was allowed to share a bathroom with other residents.

♦ One 70-year-old woman’s weight dropped to 56 pounds. At one point, according to records at the home, she was “down on her knees, lethargic.”

♦ A mentally ill man who had emphysema sat in his room, with no fan and the doors and windows closed, sweating in 90-degree heat.

The inspector found live roaches in the home’s records.

After two years of repeated violations at Commonwealth Health Care, state officials finally refused to renew the home’s license. It closed in late 1987.

Similar evidence of staff neglect surfaced at Davis Adult Manor near downtown Richmond after the home was damaged by three fires last year.

Before the fires, the home had been cited for several fire-code violations. After the fires, residents were forced to sleep amid the rubble.

Two men slept in a bedroom with crumbling plaster and gaping holes in the ceiling. Two women were moved from their bedroom into the dining room, which also had a large hole in the ceiling. Vibrations from construction workers above caused plaster dust to fall on them. They stored most of their clothes by laying them over up-ended chairs.

After an inspection, the state refused to renew the home’s license. A new owner has taken over and is renovating the home.

Greyhound Therapy

Despite such evidence of abuse and neglect throughout the system, the state continues to dump hundreds of mentally ill adults in board-and-care homes.

Many adult homes have sprung up around state institutions in rural western Virginia, resulting in what one owner calls “Greyhound Therapy.” Mental health officials in northern Virginia routinely bus mentally ill people hundreds of miles across the state to adult homes in the Roanoke Valley and far southwest Virginia — and forget about them.

They leave it up to local mental health agencies to take care of the new residents. But those agencies are often so overworked that the mentally ill get little attention. A 1986 study by the General Assembly found that one-fourth of adult homes that care for residents with chronic mental illness have no working relationship with local mental health agencies.

Mental health officials concede they often do not have the money or the people to give much support to adult-home residents.

Helen Dasse, support services director for Mental Health Services of Roanoke Valley, said her case workers are responsible for an average of 64 clients each.

“To my way of thinking, that’s still trying to put a band-aid over a crack in the Hoover Dam,” she told a gathering of adult-home owners this spring. “You want us to give you better services. I’m sorry. We can only provide so much.”

Sandy Murphy spent more than a year trying to get her 40-year-old brother, Chuck, out of a state mental hospital and into a group home near his family in northern Virginia.

Chuck, diagnosed with schizophrenia, had gone to Western State Hospital near Staunton for what was supposed to be a short stay. But because of long waiting lists in the few housing programs in northern Virginia, he got stuck in the hospital, paying about $4,000 a month out of the inheritance his father had left him.

Sandy Murphy finally gave up and placed him in an adult home 365 miles away in Abingdon, near the Tennessee border. She said the home, Renaissance House, is a good one with a well-trained staff.

But her brother is not happy, she said. “He wants to come home. He was born here. He’s lived his whole life up here. I think he feels cut off.”

Citizens have failed to demand that government officials do something about housing for the mentally ill, Murphy said. “We need to keep the pressure on. And we should not take their feeble excuses as an answer any more.”

Nowhere to Go

At the root of the problem is a housing shortage. Virginians diagnosed with mental illness have few choices about where to live. Usually, if they can’t or don’t want to live with their families and are unable to live independently, the only choice is a home for adults.

Mental health advocates say the state’s continued reliance on adult homes has stifled the growth of better housing alternatives. Although Virginia has spent more than $60 million over the past two years trying to improve mental health programs, a national survey last year ranked the state’s housing for the seriously mentally ill among the worst in the nation.

As a result, advocates say, thousands of people are stuck in state mental hospitals because there is no place for them to go.

State officials put the figure lower, but concede that there are at least 1,000 people on waiting lists in state institutions who are ready to leave but have nowhere to go.

When residents do leave hospitals, they have everything they own in an old suitcase or a paper sack. They are taken to a rest home in a town they’ve never seen before and are introduced to roommates they’ve never met before.

“You come in there with your lone suitcase and they show you your bed,” said Dasse, the Roanoke Valley mental health official. “There has to be a loss of dignity.”

Mallam, director of the state Alliance for the Mentally Ill, said dumping the mentally ill into adult homes designed for the elderly has undermined the goal of getting people out of large institutions and helping them lead normal lives in the community.

She and other advocates say large adult homes in former hospitals or old motels are often little more than small institutions themselves, and smaller adult homes usually do not have enough trained staff to deal with the special needs of the mentally ill.

Advocates like Mallam favor group homes or apartment programs run and staffed by mental health professionals.

Mallam believes that 90 percent of the estimated 4,000 mentally ill people in adult homes should be in apartment programs that give residents the supervision they need while helping them learn to take better care of themselves. Yet there are currently fewer than 1,500 beds in such programs. (See sidebar.)

A for-profit adult home has an economic incentive to keep a mentally ill resident from getting better and learning to become more independent, Mallam said. “You don’t want him to get better and move. Because then you have an empty bed.”

Mallam said adult-homeowners have also lobbied against proposals to allow the mentally ill to receive state “auxiliary grants” to live in public housing programs. The state currently gives money only to mentally ill adults who live in adult homes.

“We’ve got an industry that understandably wants to protect itself,” Mallam said.

Outside the Law

As the demand for housing has grown, hundreds of boarding houses and unli-

censed adult homes have sprung up across the state. Because the operations don’t have to follow any of the requirements that licensed homes do, thousands of residents are at even greater risk in these unregulated homes.

Upstairs at Alice Odom’s boarding house in Petersburg, an alcoholic man snoozed Sunday afternoon away, curled in a fetal position under an old purple bedspread. A pack of Richland cigarettes and a large can of Richfood pork and beans sat on the bedside table. A brown roach crawled brazen circles over the table.

Odom has been taking people into her cluttered frame house for years, a few hundred feet from the city welfare department building. She’s sheltered alcoholics, former mental patients, people in wheelchairs, and bedridden old folks — charging them $250 a month.

“Sometimes they get on my nerves,” said Odom, 60. But without her, she said, “they would have to be in the street or find them another place. Then I’d have to go on welfare. Having this place, I’m able to take care of myself.”

Her boarding house is part of an extensive, unregulated dumping ground for the mentally ill. These unlicensed and sometimes illegal businesses house much the same type of residents that adult homes do, including mentally ill people who are often poor, vulnerable, and have no one else to look out for them.

State officials have said for years that Odom is violating state law by taking money to care for four or more aged or disabled adults without an adult-home license. In 1985, welfare inspectors reported that she was housing about a dozen people in three buildings. The aging wooden houses were filthy, smelled of urine, had holes in the walls and looked like they were going to collapse in some places, the inspectors said.

A court order the following year forbid Odom from operating, but she continues to take in mentally ill people kicked out of licensed homes because the homes could not handle them. Some weeks she turns away three or four boarders. “They just always coming,” she said.

State officials not only know about unlicensed operations like Odom’s — they regularly rely on them to care for the mentally ill. A 1986 study by the General Assembly criticized state mental health officials for placing mentally ill adults in boarding houses and other unlicensed facilities. The study said that at least 16 of the state’s 40 local mental health agencies knew of unlicensed facilities that were violating the law by providing care to four or more mental patients.

It bothers some adult-home owners that anyone who cares for three or fewer adults doesn’t have to follow even the most basic requirements — such as fire and safety rules — that licensed homes must follow. “We just feel these people ought to be brought into the system,” said Bob Williams, who owns adult homes in Roanoke and Pulaski County.

Crime Without Punishment

For state officials — already stretched thin in trying to watch over the nearly 20,000 people living in licensed adult homes — the prospect of increased regulatory responsibility is daunting.

Carolynne Stevens, state licensing director for adult homes, said the state doesn’t want to “force people into too much or too little in the way of care or protection.”

But critics of the current regulations say too little protection is what residents get. In 1985, for example, a 59-yearold man died in a fire at an unlicensed Henrico County home. Fire officials said six adults were being cared for at the home.

The owner, Marie Petteway, had lost her license to operate an adult home in Richmond in 1979 for numerous safety and health violations. That same year a Henrico County judge had ordered her to stop running an unlicensed adult home at another site.

Even if officials required boarding houses and small adult homes to obtain licenses, however, they would have almost no way to protect residents from serious abuses. The state currently has only 21 inspectors for 446 licensed adult homes.

And even when inspectors find violations at licensed homes, their hands are often tied. Although many homes receive public funds, officials cannot fine owners, forbid new admissions, or cut funding to homes that repeatedly violate state regulations. All they can do is revoke a home’s license — an all-or-nothing measure that they seldom attempt.

Jo Ella John, president of the state adult-home association, said the state should fine owners to force them to improve. If an owner knew that certain violations would automatically cost $100, she said, “that owner would get his act together in a hurry. And you would have a good home, and you wouldn’t have to close it down.”

New Robber Barons

What is happening in Virginia is being repeated in adult homes across the country. Two federal studies released in March criticized federal and state officials for failing to protect residents and improve conditions in board-and-care homes.

The studies found many abuses, including rapes, beatings, deaths, fraud, crowding, and fire hazards. At a Mississippi adult home, nine malnourished adults were locked in a 10-square-foot storage room with no ventilation, electricity, or furniture. They went to the bathroom in a bucket and slept on two mattresses covered with newspapers.

In South Carolina, a staffer was having sex with a mentally ill resident who was unable to defend herself. Local social workers excused what was happening, saying it was “mere extramarital sexual relations.”

Despite repeated warnings about such abuses, the studies reported, federal welfare officials have actually cut back their efforts to improve conditions at board-and-care homes.

During congressional hearings in 1981, for example, Health and Human Services officials promised to come up with proposals for reform legislation. The agency has never followed through on those promises.

That same year, the General Accounting Office uncovered extensive fraud in the use of federal funds in adult homes. Angered by the findings, Representative Claude Pepper accused federal and state governments of trying to save money by shunting mental patients into adult homes.

“We have created a new kind of institutional robber baron who deals in slum property — and who has brought new meaning to the phrase, ‘Bring me your tired, your poor.’”

The failure to provide adequate housing for the mentally ill has also angered people in Virginia. Last year, somebody found a blind woman wandering around downtown Richmond, disoriented and inching her way along buildings with her hands.

The woman, shoeless, dirty, and emaciated, was taken to the Salvation Army. Social workers discovered she had walked away from an adult home.

For Ellen White, welfare director for the Salvation Army, the woman is an example of how society’s most vulnerable members are often at risk in “an eclectic dumping heap” of adult homes and unregulated boarding houses.

They have nowhere else to live, she said, because nobody is willing to do anything about the problem.

“We’re all engaged in this kind of denial,” she said. “We’re all implicitly looking the other way.”

Tags

Michael Hudson

Mike Hudson is co-author of Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty (Common Courage Press), and is a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1998)

Mike Hudson, co-editor of the award-winning Southern Exposure special issue, “Poverty, Inc.,” is editor of a new book, Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty, published this spring by Common Courage Press (Box 702, Monroe, ME 04951; 800-497-3207). (1996)