Massacre in Honea Path

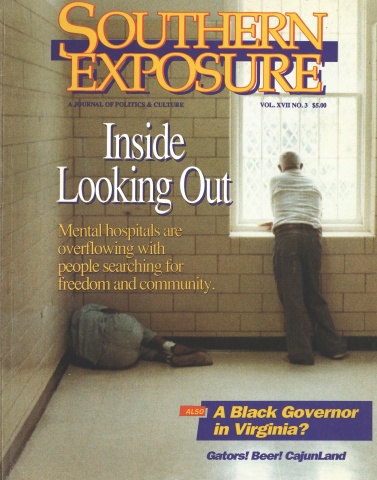

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 3, "Inside Looking Out." Find more from that issue here.

Honea Path, S.C. — There is no historic marker to record the place at the Chiquola Mill where seven strikers were shot to death on September 6, 1934. Although it was the bloodiest event of the largest single labor conflict in American history — the General Textile Strike of 1934 — today few but the town’s older residents remember.

R.A. Watkin Atkin was 30 years old when he joined 300 of his fellow workers as they marched on the mill that Thursday morning. The strikers carried sticks. The supervisors and non-striking workers inside the mill were armed with guns.

As strikers gathered around the mill, gunfire burst from the windows. During the massacre that followed, Atkin watched as two union members were shot, then kicked and shot again as they lay on the ground. He saw one of the strike’s chief organizers, a 53-year-old weaver named Thomas Ranee Yarbrough, shot in the back repeatedly. Afterwards Atkin returned to cover the bodies of the dead.

“Yarbrough got killed over there,” Atkin said, pointing to a spot by the mill. “He just tried to get people to join the union.”

At least 13 strikers were wounded. Among them was Lois McClain. Now 85 years old, McClain sat in a rocking chair on her porch and rubbed the flesh above her elbow that still contains buckshot that struck her as she helped a wounded worker escape the gunfire.

“It still comes back to us. It does me,” McClain said. “But I thank the Lord. I give my heart to the Lord, and try to forgive it, and pray more than I talk. But you know, there’s ugly things still going on in the world.”

Overworked and Underpaid

The Great Textile Strike is one of the most important — and perhaps least remembered — chapters of Southern labor history. The walkout was a grassroots union movement of unprecedented proportions, and 55 years later its defeat continues to generate fear of unions and to hamper labor organizing throughout the region.

Before World War I, hundreds of thousands of Southerners lived and worked in small mill towns like Honea Path that stretched from southern Virginia into northern Georgia and Alabama. In many cases the entire village — houses, schools, even churches — was owned by the men who ran the mills.

Entire families worked in the cotton mills; an estimated one-fourth of the labor force were children under the age of 16. They worked 12-hour days and earned about $6 a week — less than half what the same jobs paid in the North.

As child labor was abolished, mill owners began introducing faster machinery that increased work loads in the mills. Textile workers rebelled. Beginning in the late 1920s, in towns from Elizabethton, Tennessee to Gastonia, North Carolina, workers walked out to protest low pay, heavy workloads, and dangerous conditions.

Then came the Depression, and the election of Franklin Roosevelt. Bolstered by Roosevelt’s radio “fireside chats” advocating labor rights, Southern workers began joining the United Textile Workers Union in droves. Membership soared from 15,000 in early 1933 to 270,000 by August 1934.

Although the Roosevelt administration ordered the textile industry to pay a minimum wage of $12 a week and limit the work week to 40 hours, employers responded by speeding up production lines, firing workers who couldn’t keep up, and shutting mills for weeks at a time.

Workers were outraged. “If ain’t something done at once,” one South Carolina worker wrote President Roosevelt, “there’s going to be war.”

When the national union failed to confront the industry for breaking the law, workers took action themselves. In July 1934, 40 Alabama locals walked off the job. Union delegates meeting at a convention in August voted overwhelmingly to join them. They called for a general strike to begin on Labor Day — and most of the pressure came from leaders of newly formed Southern locals.

“The union never had more than a handful of paid organizers in the South during the whole strike period,” said Jacquelyn Hall, director of the Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina. “It was really a welling up from below.”

Within weeks an estimated 400,000 textile workers were on strike nationwide. The streets of mill towns like Honea Path were soon overflowing with defiant, jubilant workers and their families.

Small-Town Dictatorship

R.A. Atkin and his wife Ethel remember little about the causes of the strike, but they recall all too well the day the guns turned on them.

Atkin was 19 years old when he quit farming, got married, and went to work in the mill to make more money. Ethel had started work at the mill about two years earlier at age 14.

When the strike came, the Chiquola Manufacturing Company was the only industry in the town of 2,740 people. The mayor was Dan Beacham. He was also the mill superintendent.

By that time, R.A. was working in the weave room “doffing warp,” and Ethel was working in the spinning room. The couple had four boys, ages three to eight.

The Atkins each earned $ 12 a week, the newly enacted minimum wage, but they still had difficulty supporting their family. They paid the company $4.80 a month for their four-room house in the old section of the mill village. Electricity and water were supplied by the mill.

“You had to live tight, do everything you could to raise a dollar then to live when you was raising a family,” Atkin recalled.

When unions began organizing at nearby mills about six to eight months before the strike, about half of Chiquola Mill’s 600workers signed up. Atkin refused to join, saying the only thing he wanted to belong to was his church.

The union held meetings in a building atop a hill within sight of Atkin’s home. “They’d have that thing full over there,” he said, pointing to the site from his chair.

Lois McClain attended the meetings. “We had a union. It used to be where I just spoke my piece. When I thought a thing I told it,” she laughed.

“We didn’t have no money, and we couldn’t buy new dresses and things like that So I got up and told them, I said, ‘Now, this one can buy a dress and the other one can buy a dress.’ I said, ‘How come? I thought we were in this thing together.’ I said, ‘We can’t buy new clothes and got children to feed.’”

Many people in town agreed with McClain. “Back then the town was operated under a dictatorship, because the superintendent of the mill was mayor of the town,” said a resident in his 80s who asked not to be identified for fear of making “enemies” at his age. ‘The company wouldn’t recognize the union. That was the trouble. The majority of the people were wanting the union and the company didn’t want it.”

Shoot to Kill

On the day of the shooting, McClain said, the strikers originally planned to have only the male workers march on the mill. But after some women crossed the picket line and entered the mill to work after the 6 a.m. shift change, the strikers decided they would call on the women who were staying out.

Two women came by and encouraged Ethel Atkin to join the workers at the mill and offered to watch her children and take care of her chores. “They said if . . . there was more out than there was a’ workin’ they was going to stop off and settle it. We didn’t belong to no union. The day they was going to settle it, I was going to stay home. I wasn’t going. I didn’t have nothing to do with it.

“Some old women came by beggin’ me to go saying, ‘Show your colors. You have to go over there and let them see you.”

Atkin went. “It was the awfulest thing that ever happened to me,” she recalled. “The people on the outside weren’t expecting nothing. . . . [They] was wanting to settle it peacefully, to show their colors that they was honest.”

Her husband was near the mill’s main entrance when the shooting started. He said Mayor Beacham was inside the mill with loyal workers armed with guns and gave orders to “shoot to kill.”

“The non-union was inside the mill shooting ’em outside the window,” Atkin said. “If they had guns on both sides there’d have been plenty of killing. It was just like shooting a hog in a pen.”

Ethel Atkin said she tried to flee when she saw the guns inside the mill.

“I said, ‘This ain’t no place for us.’ When we turned it commenced to poppin’. Well, we didn’t go far till we started trying to help those on the ground.

“We pulled pillows out of a woman ’s window and stuck it under their heads and fanned them. They died. We went on. I said, ‘Let’s go.’ We went on, and there was another man dead on the sidewalk.

“I prayed a lot to forget that,” she said.

“Some of them in that window with them guns pointed out had younguns, grandchildren standing down there in front of there. I didn’t think nobody was that mean. You can’t look at people’s faces and tell what’s in their hearts.”

In the midst of the shooting, Lois McClain saw her friend from the spinning room, 20-year-old Nell Baucam, sitting on steps near the mill. She had been shot in the arm and was bleeding heavily.

“I told her, ‘Nell, you can’t sit there. . . . Get up and come on.’ And I grabbed her.”

Then McClain herself was shot. “She was shot with a bullet. I just had a shot out of a gun, out of a shell. I didn’t bleed too much. I didn’t know even which way the shot come in. All I knew it was in my arm. But I didn’t turn her loose until I got her away from the steps.”

“How Dirty It Was”

The elderly resident who asked not to be identified also witnessed the shooting. “I had some good, close friends to get killed,” he said. Among them was Edgar Matthew “Bill” Knight, a weaver who also ran a grocery store in a wooden shotgun shack on Hammett Street.

Knight was about 43 years old when he was killed. He left behind his wife Eunice and four children. His only daughter, Ruth, 16, was with him when he was shot.

R.A. Atkin saw the shooting begin, saw Knight die. “It lasted about six or seven seconds, and they killed two on the ground there, and there at the door they killed old man Yarbrough. Across the street on the sidewalk they killed Mr. Cannon. Down at the end of the mill Bill Knight was laying there dead. Down about the second house there was another one, Pete Peterson, he was dead.”

Atkin also said he watched a policeman and a mill supervisor shoot two men after they had fallen. “Lee Crawford and Ira Davis, they shot them after they knocked them down on the ground. Kicked ’em over and shot ’em again. And when Yarbrough was down there standing up with both hands up, they shot him in the back with buckshot.”

McClain said she also watched Yarbrough being shot. “He was trying to get away and they shot him.” Dr. E.R. Donald, who performed an autopsy, later testified that he found bullet holes in the backs of Peterson, Knight, Claude Cannon, Charles Rucker, and Yarbrough.

Donald said that Yarbrough was shot 10 times.

“Me and Doc Don come over to that house right yonder on Kay Street,” recalled Atkin. “One boy was shot in the leg, we worked on his leg. We went back over there and pronounced all them dead.

“We covered up Yarbrough, and Lee Crawford and Ira Davis right there on the mill ground.”

“It didn’t bother me till that night when I laid down. I likely went all to pieces, just thinkin’ about how dirty it was.”

Two days later, on September 8, 10,000 people gathered in the middle of a field to bury the first six victims of the Chiquola Mills clash: Yarbrough, Peterson, Knight, Davis and Crawford, 26, and Cannon, 39. The seventh striker, Charles Rucker, 39, died the next day. Newsreel cameras rolled and airplanes flew low over the crowd to take pictures.

An inquest was conducted and several non-striking workers were tried for the shootings, but no one was convicted in the deaths of the workers.

Concentration Camps

Honea Path was not the only town rocked by violence. About an hour after the massacre, a strike supporter was fatally shot outside the Dunean Mill in Greenville, South Carolina. The mayor called for martial law, even though the governor had already called out every unit of the National Guard.

Caravans of strikers called “flying squadrons” faced bayonets, machine guns, and tear gas when they tried to shut down mills. In Georgia, Governor Eugene Talmadge ordered the largest peacetime mobilization of troops in state history and imprisoned 126 strikers in a barbed-wire “concentration camp” near where Germans had been incarcerated during World War I. In North Carolina, National Guardsmen bayonetted two strikers, fatally injuring one, in a confrontation at a hosiery mill in Belmont.

Many mill towns were bitterly divided by the strike. In Honea Path, hundreds of strikers were evicted from company-owned houses. Those who continued to work were jeered by strikers as they filed past the picket lines and into the mills each day.

The anger has lingered for more than half a century.

“I tell you it’s made a difference in us Honea Patheans,” said Ethel Atkin. “It’s been hard to live down. Of course, I know you have to forgive people, but you still think of it.”

Her husband remembers that churches wouldn’t allow funeral services for the dead strikers. All but one of the dead was from Honea Path.

“People quit going to church,” he said. “There was people going to church with one another, and shot them out there on the ground. It just tore the churches up.”

Generations of Fear

When the strike ended after three weeks with few tangible gains, it left more than bitterness behind. Few locals were recognized, many strike leaders were blacklisted, and the defeat reinforced a sense of powerlessness among many workers.

Atkin remembered that a few years after the strike, union organizers tried to distribute flyers outside Chiquola Mill. Workers didn’t take them.

“They wouldn’t pay ’em a bit of attention,” Atkin said. “You get burnt before, you’d watch it next time, wouldn’t you?”

Ethel also said the strike turned workers against the union: “I wouldn’t want to have to kill somebody that way to get it.”

“There won’t ever be another union,” her husband said. “There hasn’t been another one since.”

A sense of defeat runs strong among those who remember the strike. Joan Carter, an organizer for the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union, said she often encounters horror stories about the strike.

“While out in the field organizing, I run into people who talk about the strike, about the National Guard being on top of the buildings,” she said. “This is the thing that sticks out in their minds the most when you say ‘unions’ — this strike. It’s been passed down through generations. . . . It’s just left a fear on people about the union.”

Some workers overcame that fear and kept organizing for better pay and working conditions. Among them was Jesse Mitchell, who worked at the Chiquola Mill for 12 years before being fired several months before the strike on what he later called “a trumped-up charge because of my union activities.”

Although his brother-in-law, Claude Cannon, was killed in the Honea Path shooting, leaving behind a wife and six children, Mitchell later helped in an organizing drive at the Brandon Mill in Greenville. During World War II he became president of the union local at Woodside Mills, where strikers had been teargassed by National Guardsmen during the 1934 strike.

At the Chiquola Mill in Honea Path, however, there is no union. Today the mill is owned by Springs Industries of Fort Mill, the largest manufacturing employer in the state. The factory employs about 590 non-union workers who make industrial fabrics.

Older townspeople remember the strike, but they seldom talk about it among themselves. The story of what happened in Honea Path “is never going to be told,” said Norman Hammett, the son of a mill supervisor who was inside Chiquola Mill the day the strikers were gunned down. “You can understand why — because there was brothers against brothers. It was another Civil War.”

Tags

Jim DuPlessis

Jim DuPlessis is a reporter for The Greenville News in Greenville, South Carolina. (1989)