“Like Lightning Striking”

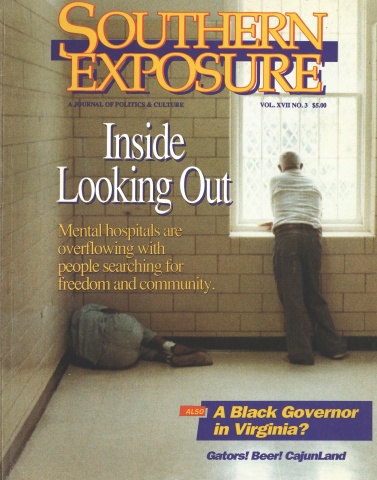

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 3, "Inside Looking Out." Find more from that issue here.

John Baggett is a gentle, bearded man who lives in Raleigh, North Carolina. As director of the state Alliance of the MentallyIII (AMI), he lobbies for families like his own who care for relatives with severe mental illnesses.

As the mentally ill have been “deinstitutionalized” — moved out of psychiatric hospitals and returned to their families — AMI has become the fastest-growing consumer movement in the country. In its first decade, the group has grown from just 200 families to more than 70,000. “If we keep that up,” Baggett laughs, “by 1992 everybody will be a member.”

My story begins with my son John Mark’s illness, which came on rather suddenly when he was 17. Prior to that he was a gifted and talented young man with a bright and promising future. We noticed he was having some school problems and drug abuse problems. When we first saw signs of the illness, we thought it was substance abuse.

Our denial about the mental illness kept us from seeing what was there. We should have been brighter, we should have known that we were seeing signs of illness. But like many families, it was the last thing we wanted to admit to ourselves. It was too horrible to see.

Our introduction to the mental health system let us know very quickly that things didn’t work the way they’re supposed to. Our son did not want to be hospitalized, so we had to go through an involuntary commitment proceeding. It created an adversarial situation where we had to testify against our own child. We were saying, “Here’s a sick child, he needs help,” and the service system was saying, “We can’t do that without going through this system.” It was a rude awakening for us.

He was hospitalized. He went to a private psychiatric facility, and he came back a few months later, a little better but certainly not well. Within a matter of weeks he was back in a serious psychotic condition. That was the first of many hospitalizations. We were not well off, and we had exhausted our resources on his initial treatment. Our insurance was very poor — it covered a very small part of his psychiatric care.

From then on, we dealt with the public mental health system. We could no longer afford the private system.

John Mark was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. We did not know what that meant, and nobody really explained it to us. One of the popular theories was that it was caused by families. So we felt like, “Oh, my gosh, we’ve done something terribly wrong.” We struggled a lot with the guilt, and we also found that a lot of families went through that.

What we know now is that he suffers from a genetically based brain disease. It’s a no-fault disease, like diabetes or muscular dystrophy. Kidneys can be diseased, hearts can be diseased, and brains can be diseased. He just happens to have a brain that doesn’t function normally.

When you have a serious mental illness happen in your family, as it did in ours, it is like lightning striking. It just catches you off-guard, and it’s devastating when it happens. The person who used to be your son isn’t anymore. Parts of him are still the same, but he’s been changed by what’s happened to him. There is a loss, and you grieve over that.

Over time, however, you also learn to love and appreciate the new person who has taken his place. I have great, great affection and admiration for his courage in just getting through, day by day. All of us sometimes have difficulty getting through the day. But only a person with a serious brain disease such as schizophrenia knows the incredible amount of courage and energy it takes just to struggle through a day-to-day existence.

One of his symptoms is that he hears voices. And the voices he hears are just as clear to him as my voice is to you right now. Those voices can be very distracting. They can be very loud. They can be very accusing, and they can be amusing.

The voices make it hard for him to concentrate. He couldn’t last more than two or three days in a job, because he was so distracted by what was going on in his head. He went through I don’t know how many jobs before he got totally discouraged.

He was living at home, and we were really struggling. He would get off his medication and get very, very sick. We were in almost constant crisis. He would leave home, go out on the road, and become homeless for a while. It worried us greatly; something very serious could have happened to him out on the streets.

The only services available were outpatient care by a psychiatrist at a mental health center, or inpatient care at the state hospital. Those are not very good choices. There were also services in other states that weren’t available to us — services like psychosocial clubhouses or residential group homes.

We knew John Mark couldn’t live independently at that point, but we also knew it was not healthy for him to be living at home. An adult person in his late twenties living with mommy and daddy is not the healthiest situation. His illness made it very stressful for everybody.

We had a very disturbing crisis that made it clear John Mark couldn’t continue to live with us. We managed to get him committed to John Umstead Hospital in Butner, but three days later they wanted to send him home. He wasn’t even stabilized; it was absolutely ridiculous.

I went to the hospital and sat down with the doctor and one of the social workers and said, “He cannot come home, and he has no place else to go. If you release him, I will hold you accountable.” They decided to keep him.

Three weeks later they wanted to let him go again. I went back and made the same speech. We talked about how he was sitting on the wards all day, getting medication and what we call “TV and cigarette therapy.” It was just a warehouse.

I pushed to get him additional treatment, and he started seeing a staff psychologist. She had a no-nonsense approach, and that made a tremendous difference. She didn’t do any of this psychoanalytical stuff. She tried to get him to accept the fact that he was ill, talk with him about coping with it, and develop better skills for dealing with people.

We noticed a difference right away. We’d take him a little present like a shirt or something, and he would say, “Thank you.” We hadn’t heard “thank you” in months.

Then we got really lucky. The hospital started a program to help long-term patients learn skills so they could live in the community. We were fortunate enough to get him in that program.

He ended up staying in the hospital 11 months. If they had released him in three days, or three weeks, or even three months, I don’t think they could have provided the training he needed to live on his own.

Now he lives in a mobile home which I own. He has a roommate, and they rent the mobile home from me. One of the reasons I own it is because mentally ill people often have trouble with landlords. We’ve had that arrangement now for almost five years, and it’s worked well most of the time.

We have had some crises along the way. But he’s independent; he often goes for several days without our needing to check up on him. He doesn’t ask for help except when he needs it.

He had a crisis recently with his roommate, who took all of my son’s medicine and attempted to take his own life. My son tried to reach me, but he couldn’t get me right away, so he called 911 and got the emergency people to take the roommate to the hospital. My son had done all he could, so he went to bed. He called me the next morning. He handled the situation very, very well, and didn’t really need me to resolve it.

He’s made a lot of progress, and we have too. We never know when there’s going to be another crisis. You learn just to be grateful for the days when you don’t have a crisis, and to get through the ones when you do.

I felt emotionally very isolated. Then in 1984, seven years after Mark got sick, I got an announcement in the mail about a meeting to form a state affiliate of the Alliance of the Mentally Ill. I didn’t know anything about it, so I drove to Greensboro where the meeting was being held.

It was my first time in a roomful of people who had been through what I’d been through. I found that there was a great deal of healing for me just talking to other people about it. I’d never attended a support meeting of family members.

There was a time when I was very ashamed of my son’s illness and tried to keep it a closely guarded secret. Joining AMI made me come out of the closet and say, “Hey, there’s nothing to be ashamed of here. This is a devastating disease, and it has a terrific impact on the mentally ill person and their family.”

I was impressed that the Alliance not only provided support, it provided education for families. It was also committed to advocacy for changes in the mental health system. Our experience had impressed upon me that there was a real need for change. I began to ask questions about why things are not better than they are. And one of the biggest answers was that there wasn’t enough money devoted to provide better services.

A state official got up at that first meeting and talked about how wonderful deinstitutionalization was. I was appalled! What deinstitutionalization had meant to me was, I couldn’t get my family member into the hospital when he needed to go. When he went in, he didn’t stay long enough to get stabilized. That’s the way it really worked. It just got people out of the hospital — it didn’t provide appropriate care in the community.

The state didn’t commit money to create community services. So the family ended up with the primary responsibility for taking care of the mentally ill. The system transferred the care from the hospitals to the families.

After the meeting, I went home and helped organize a local chapter of the Alliance. Two years later I was hired as executive director of the state AMI. So I’ve been very involved in helping to build a public consensus to make mental illness a state priority.

Traditionally, the mental health system has emphasized a wide variety of mental health problems, rather than serious mental illness. Many resources were going to serve what we call “the worried well,” and very few dollars were going to people with serious illnesses like manic depression or schizophrenia.

In 1985 the state set aside no money for people with chronic mental illness. In 1986 we got them to budget $1.25 million. Today there is close to $30 million dollars set aside — and that’s a direct result of the advocacy of the Alliance for the Mentally Ill.

The reason for our success is clear: We are family members; we have a direct stake in what happens. This is not a liberal cause; this is a life-and-death cause. Our own flesh and blood are suffering from these illnesses. It strikes liberals and conservatives and Republicans and Democrats; it is not a respecter of persons. Our members tell their representatives, “We’ve got to make mental illness a priority.” Each year we make some progress.

The day of deinstitutionalization is over. It is time to quit saying, “Either we’re going to serve mentally ill people in the hospital or we’re going to serve them in the community.” It is time to talk about providing comprehensive services that include hospitals, job training, housing — whatever people need.

We have won an important symbolic change. The state no longer defines success in terms of getting mentally ill people out of the hospital. It defines success in terms of whether or not people are being served. There are over 84,000 people who suffer from severe mental illness in our state, and only a third receive services. There is a tremendous unmet need out there.

I get a lot of credit because I’m in the press, but I don’t really do the lobbying. I simply inform grassroots families of what’s going on and make suggestions about what they can do to see that the legislature gets the job done. They’re the ones who do the effective lobbying — the citizens of the state.

It is not easy to take institutions that have been around a long time and change them. Families and primary consumers need to be involved in any policy that’s being made. We did get past the legislature a bill that ensures there is at least one family member on the governing boards of local mental health centers.

As family members, we are stuck with the problem. We aren’t going to go away. We’re going to continue to grow, to be stronger — and the legislature is going to continue to pay more and more attention to us.

Tags

Grace Nordhoff

Grace Nordhoff is a graduate student in social work at the University of North Carolina. (1989)

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.