This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 3, "Inside Looking Out." Find more from that issue here.

Tuscaloosa, Ala. — Tom Hammond was an honors student at Louisiana State University when his mother died of lung cancer in 1969. After her death he started feeling paranoid and went to live with his uncle in Alabama. A year later he was committed to Bryce Hospital — one of the oldest state mental hospitals in the South.

“The hospital was an extremely humbling experience,” said Hammond. ‘They told you you were crazy and would always be crazy. They told me I could never get a job.”

Nineteen years later, the stigma of mental illness Hammond first encountered inside Bryce still hovers over his life. According to Tom, everyone in town knows he’s crazy. He knows where he can go and sit without being asked to leave. He knows where he can get a free loaf of bread.

He’s been able to get jobs, but doesn’t keep them. “After a few months I get bored and then I get hateful and then I quit. It’s just one no good job after the next.” Sometimes when he looks for work, he can’t even get his foot in the door. “They say there’s no vacancy, but you can see other people getting hired.”

When his marginal life in the community overwhelms him, Hammond goes back to Bryce. He has been in and out of the hospital several times, but things have changed since his first trip in 1970. Back then, Bryce was the state insane asylum — a place where people were sent away, never to return. Now it’s a state mental hospital — a way-station where people like Hammond come and go through revolving doors.

The change can be traced to a landmark court case that started the year Hammond first entered Bryce. The case — called Wyatt v. Stickney — pitted the staff and patients of Bryce against the administration of then-Governor George Wallace. The result was the first federal ruling to establish that mentally ill people have a constitutional right to treatment.

Wyatt brought sweeping changes to the mental health system in Alabama. Acting under orders from a federal judge, Bryce opened its doors and cleaned up its act. Today there are fewer patients, more staff, and better conditions.

But Wyatt also sparked a 14-year showdown between state bureaucrats and mental health reformers that left many patients like Tom Hammond living on the edge. Almost two decades have passed since the case began, but the state is just now starting to create community services for those who are released.

Some, like Hammond, don’t even feel that Bryce has improved. “It’s a minimum security prison,” he said. “Bryce is worse except for one thing. You can get out now.”

A Human Warehouse

Bryce stands at the end of a long driveway, its elegant columns gracing the entrance to the hospital grounds. Green farmland stretches from the highway on one side to the University of Alabama campus on the other. There is no barbed wire, no armed guard watching from a gun tower. You can simply walk right into the hospital, and — if you’re lucky — you can walk right out.

The hospital building itself is noteworthy. Completed in 1861 after social reformer Dorothea Dix lobbied the state to provide care and housing for the mentally ill, Bryce was expanded over the years until today it is the second longest continuous building under one roof in the United States, outdistanced only by the Pentagon.

Bryce was originally designed to house 250 people, but it gradually grew into a giant human warehouse packed with more than 5,000 patients. Almost all were confined to huge, open wards where as many as 80 patients slept in beds crammed side by side. Most spent their lives in the hospital, with little to do all day but rock in chairs provided to soothe whatever craziness was supposedly going on inside their heads. Many received routine shock treatments; others were lobotomized, portions of their brains cut out in the name of mental health.

The hospital had also become a warehouse for the state’s old and undesirable. An estimated 1,600 elderly residents and 100 mentally retarded patients received no treatment at all. “We just dumped them,” said Paul Davis, a reporter who covered the Wyatt lawsuit for the Tuscaloosa News. “Bryce was known as our state nursing home. You could go to your probate judge and get your medical doctor to sign a form that says ‘Granny’s getting old’ and the sheriff would take her off to Bryce.”

By 1972, neglect and abuse were rampant. “Thousands of people received no treatment whatsoever,” said Jack Drake, who took on the Wyatt case as a young lawyer in Tuscaloosa. “Terrible things happened to people who never should have been there.”

The files of people who died in Bryce revealed ghoulish conditions. Two patients were scalded to death, and another died when a patient stuck a garden hose up his rectum and exploded his intestines. “This happened just because one aide watched 250 to 300 patients,” Drake said. “Bryce was just a horrible place. It was a nightmare.”

The neglect stemmed from understaffing. The hospital had only one Ph.D. clinical psychologist, three medical doctors with a smattering of psychiatric training, and two social workers with masters degrees to treat more than 5,000 patients.

Bryce typified not just the worst in neglect of the mentally ill, but also the worst of Southern racial discrimination. Soon after the hospital opened, black patients were confined to separate “lodges.” In 1902 the state sent all 318 black patients to an old military barracks near Mobile which eventually became Searcy Hospital, the third separate mental hospital for blacks in the United States.

Conditions at Searcy were even worse than at Bryce. In 1968, there was but one licensed physician and a few unlicensed Cuban refugee doctors to treat 2,200 patients. Wards were overcrowded, with iron grillwork covering the windows and yellowed, dirty plaster on the walls. Heating ducts and pipes for water and sewage were exposed overhead. Patients were beaten with whips made from electrical cords. (See sidebar.)

By 1970, when mental health systems around the nation were releasing patients to the community as part of a movement known as “deinstitutionalization,” the conditions at Bryce and Searcy were at their worst. Alabama ranked last in the nation in daily per-patient expenditures. By 1971, the state was spending only $7.55 a day per patient, at a time when the Southeastern average was $12.36 and the national average was $14.90. The daily food allowance for patients at Bryce was less than 50 cents a day.

Here Comes the Judge

There were those in Alabama who wanted to shake up the system — and one of them was a self-avowed troublemaker named Stonewall Stickney. In 1968, Stickney became the state’s first full-time commissioner of mental health, and the first leader of the mental health system who was not directly connected to Bryce Hospital. The following year he seized upon a federal court order to integrate Bryce and Searcy and, despite interference from the governor’s office, completely desegregated the hospitals by the end of 1970.

When the state cut the budget for mental health services that same year, Stickney immediately laid off about 120 employees at Bryce. “We planned to create so much trouble that the legislature and the governor could not afford to overlook the department anymore,” Stickney said later.

Stickney was hoping to create a crisis, and he succeeded. Several Bryce employees and a patient, Ricky Wyatt, filed a complaint in federal court in October. “The lawsuit originally filed was an attempt to save jobs,” recalled Jack Drake, one of the original attorneys.

Federal Judge Frank Johnson refused to hear the case. But as the plaintiffs were leaving his chambers, Johnson reportedly muttered to himself, “It seems to me you’d be more interested in the patients’ rights than the rights of the staff.”

The employees were back before the judge several weeks later, their case focused solely on the patients’ constitutional right to adequate treatment. This time, Johnson consented to hear the case. Wyatt v. Stickney was under way.

The lawsuit quickly exposed the horrible conditions at Bryce and Searcy. In March 1971, Johnson ruled that the thousands of long-term patients being warehoused at Bryce had a constitutional right to treatment. “To deprive any citizen of his or her liberty upon the altruistic theory that the confinement is for humane therapeutic reasons and then fail to provide adequate treatment violates the very fundamentals of due process,” Johnson ruled.

Johnson expanded the case to include residents at Searcy Hospital and the Partlow State School and Hospital for the mentally retarded, and gave the state six months to institute a treatment program at Bryce. When the state failed to do so, he ruled that patients were being forced to live in substandard conditions. “The dormitories are barn-like structures with no privacy,” Johnson wrote in December. “There is not even a space provided which [a patient] can think of as his own. . . . The toilets in restrooms seldom have partitions between them.”

As the case continued, the court heard testimony from some of the foremost mental health authorities in the United States. Finally, on April 13, 1972, Judge Johnson established 35 medical and constitutional standards governing the treatment of patients in Bryce and Searcy. They became known as the Wyatt Standards, and they established one of the first “bill of rights” for the mentally ill.

The rights Johnson enumerated were remarkably simple. Mental patients, he declared, have a right to wear clean clothes, receive visitors, send mail, exercise, interact with the opposite sex, go outside, and refuse lobotomies, shock treatments, and excessive medication.

Mental health reformers across the country hailed Wyatt as a landmark decision. “Symbolically, it marked the transition of Alabama from disgrace to respectability,” said Dr. E. Fuller Torrey, who heads a national watchdog group that rates state mental health systems.

“I think we had to be just about kicked into compliance,” explained David Marshall, a former Alabama mental patient who now heads the Coalition of Mental Patients, the largest such group in the South. “That’s the history of our government over the past 20 years. We tended not to correct a lot of things until a federal judge explained it to us. Schools, prisons, mental institutions — all those things were reformed by federal courts. I’m sorry it had to be that way, but I’m glad those courts were there.”

“Broken Promises”

Although Johnson had placed the state system under federal control and ordered that “neither funds, nor staff and facilities, will justify a default by defendants in the provision of suitable treatment for the mentally ill,” the state refused to devote enough resources to improve mental health care. The Wyatt battle was over — but the war had just begun.

The fight was ultimately over money. “It would cost $1 million in staff per 250 patients” to improve conditions, said Paul Davis, the reporter who covered the case. “The state had figured out that ‘That’s not going to bankrupt us because we’re going to send all the Aunt Bessies home.’”

The state was wrong, and conditions at Bryce remained substandard. In 1975, attorneys filed a motion alleging that doctors at Bryce were ignoring Wyatt standards and failing to follow accepted procedures in giving patients shock treatments. “We still cannot boast that our state institutions provide a humane psychological and physical environment,” Judge Johnson noted.

Advocates for the patients wanted the court to order the state to fund the hospitals adequately, but the state continued to fight to have the original standards eased. Finally, after 14 years of legal wrangling, the two sides declared a truce. The state agreed to spend more money on mental health care and secure accreditation for its hospitals. In return, patient advocates agreed to abolish the federal court office monitoring state compliance with the Wyatt standards. Judge Myron Thompson reluctantly agreed to the settlement, citing what he called “a trail of broken promises” by the state.

The immediate changes Judge Johnson had ordered in 1972 were still not in effect when the settlement was signed in 1986. Change, it seemed, did not come quickly to an antiquated system.

“That was the frustration for the plaintiffs and Judge Johnson,” said Charles Fettner, the current director at Bryce. “They said, ‘Here’s the plan — do it.’ And it didn’t happen. I don’t think it was because there was resistance on the part of the staff, but because of the difficulty in overhauling a system that had been in place for 110 years.”

Wyatt Babies

Despite the stalling and legal battles, Wyatt gradually succeeded in improving conditions at state mental hospitals in Alabama. Today there are fewer patients, more staff, and better funding at both Bryce and Searcy.

“You could get someone into Bryce in a hurry, and it was almost impossible to get out,” recalled Marshall, the head of the patient coalition. “That’s been changed. It’s more difficult to get people committed, and they have to be evaluated regularly and discharged if they don’t meet the requirements.”

“It cut the Bryce population by 80 percent, created a separate nursing home facility and a separate facility to handle prisoners,” Marshall continued. “There are more psychiatrists now, and stringent requirements for shock treatments.”

Patients also spend much less time in the hospital. “In the 1970’s most of the patients were long-term,” said Emmett Poundstone, associate commissioner for mental illness. “The average length of stay was years, but now it’s much shorter.”

Figures obtained from the Alabama Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation show just how systematic the changes have been. In fiscal year 1971, the department spent $26 million on its mental health facilities. In fiscal year 1988, it spent $226 million. The number of patients statewide has dropped from 8,100 to 2,000, while the number of staff has risen from 2,100 to 6,000.

“I’m one of the Wyatt babies,” said Dr. Cynthia Bisbee, a clinical psychologist at Bryce Hospital. “After the settlement in 1972, they started hiring people right and left. I was one of the people who could breathe and had a degree.”

Bisbee put her degree to work trying to improve care for patients at Bryce. In 1982 she helped found a new program called the NOVA Unit to “provide a more comprehensive approach to treatment.”

Patients in the unit are people from 18 to 35 years old who have been diagnosed with chronic schizophrenia — one of the most severe and least understood of all mental illnesses. The unit is small, so residents have close contact with staff. They take mega-vitamins, stick to no-caffeine, no-sugar diets, and keep busy from 6:30 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. The goal of the unit is to discharge patients within one year and provide follow-up after they leave.

“We’ve had people try to move to the state to get their family members into the program,” said Bisbee. “There’s nothing else like it in a state facility.”

The unit feels a little different from other parts of Bryce. The walls aren’t as drab, and the unit is small enough so that patients can decorate their rooms without their belongings being stolen or confiscated.

Stanley McCoy, a 36-year-old black man, lives on the NOVA Unit. While Judge Johnson was listening to testimony in the Wyatt case back in 1972, McCoy says he was “hearing voices and having hallucinations.” Since then, he has been in and out of Bryce for 15 years — and he has noticed the difference.

“It’s changed,” McCoy said. “It’s become more comfortable in here.”

McCoy especially likes the NOVA Unit. “I think this program has done a whole lot for me. All I want is to be able to think for myself. They let you do things here because I choose to do them, instead of jolting you all the time.”

Brenda Russell, a 35-year-old black woman born and raised in Mobile, also lives on the NOVA Unit. She said her trouble began when she dated a boy whose parents were “involved in witchcraft — they put a spell on me.” The onset of her illness confuses her to this day. “When I was a kid, I was a perfect kid in school. I just got fouled up as an adult.”

Russell called the NOVA program “the best one up here. They treat everybody the same.”

Behind Closed Doors

Although McCoy and Russell have high praise for the NOVA program, neither has much good to say about the rest of Bryce. The hospital did not even begin providing active treatment for many patients until 1986 — 14 years after the Wyatt ruling. A recent tour of the hospital reveals that treatment remains haphazard at best — and that whatever the improvements since Wyatt, most patients still yearn to be free to leave.

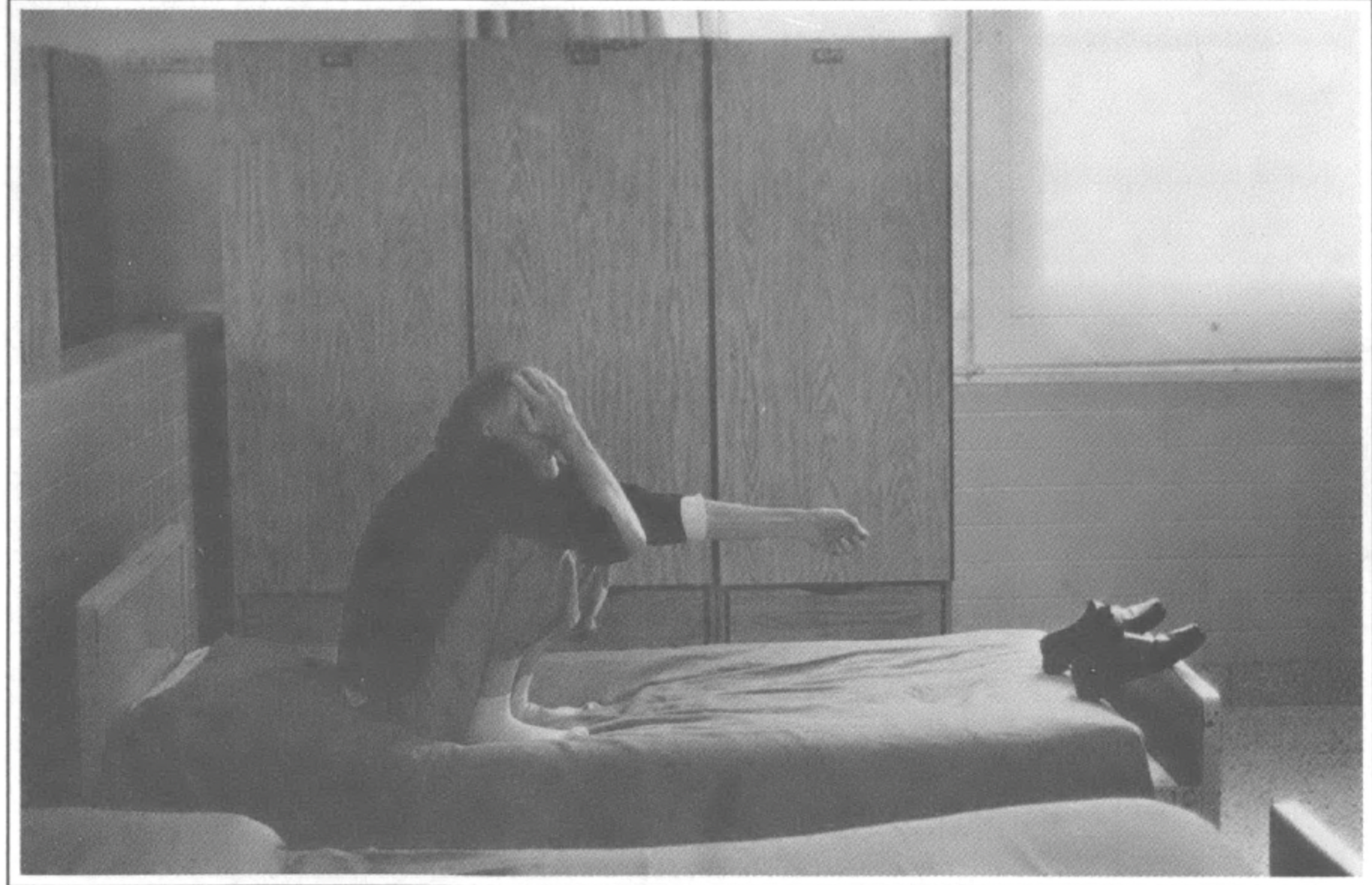

“No one really knows what it’s like when visiting hours are over and they shut the door,” said David Marshall, reflecting on his years in mental hospitals. “You’re utterly helpless. You’re frightened. You’re sick. And there’s no way from getting away from the fact that you are mentally ill.”

Half of the 660 long-term patients at Bryce live in three units of the Structured Living Program (SLP) East. Patricia Scheifler, head social worker for SLP East, leads the way down the long corridors and through the wards.

Scheifler is armed with keys to get in and out of each of the units. She points to exposed pipes and peeling paint, saying the hospital is building a new facility to house “chronic” patients.

Each unit is painted different shades of pale green and yellow. As the hues change from unit to unit, so does the mood of the patients. In the “open” unit, a few people talk to each other as the sun shines in through the windows. On the “intermediate” unit, patients pace up and down the halls. On the “closed” unit — the most restrictive ward at Bryce — many people lie on their beds with their heads pushed deep into their mattresses.

As Scheifler unlocks the door to the closed unit, a woman falls to her knees, screaming and wailing. “Help me, Jesus, please help me! Take me out of here, Lord, please Lord, take me home!”

Scheifler walks back through the intermediate unit, heading toward the exit. As she pulls out her keys, a patient grabs her arm and begins to plead with her. “Let me go, darlin’, let me go!” the woman demands. “If I can go home, I’ll be all right. I just need to go home. Let me go!”

Safely through the exit, Scheifler slams the door, leaving the woman behind. She pauses, slightly embarrassed by the incident “I reflect on that when I go home at night,” she says. “I go home at 4:30 every day. These are people who can’t leave.”

Born Free

For the thousands of patients who have left in the days since the Wyatt decision, things haven’t been much better on the outside. Patients don’t stay as long at Bryce these days, but they come and go more often. “We expect to see half of them come back,” said Charles Fettner, director of Bryce.

Brenda Russell has come back several times. When she was released from Bryce in 1985, for example, she went to live with her mother. “I looked for a job, but I had a mental record and couldn’t get one. Instead of giving me a break, people put a stumbling block in my way.” When she got pregnant, Russell said, her mother called the police and had her sent back to Bryce.

“I was a very intelligent person up until I started going to mental hospitals,” Russell said. “I’d rather live in the community. I mean, I was born free. Why can’t I live free now?”

Russell’s story is a common one — and it reveals one of the flaws in the original Wyatt decision. The court ordered that hospital conditions be improved, but failed to require the state to establish community mental health services throughout Alabama.

“Unwittingly, the community system was virtually ignored in Wyatt,” said Dr. Robert Okin, assistant professor at Harvard Medical School. Okin added that a state survey shows that one-third of all patients in Alabama mental hospitals would be better off in the community, but continue to be warehoused because of the lack of local services.

Okin also chairs the Wyatt Consulting Committee, a group of “experts” set up by the court to oversee the 1986 Wyatt settlement. In just three years, the committee has managed to push the state to start developing mental health services in local communities.

To get things moving, Okin brought Alabama mental health professionals to Massachusetts so they could see effective community services for themselves. “It really made a difference,” Okin said. “Could their clients do well in the community, given their severe symptoms? That question was virtually answered at a glance. Actually talking to clients in a different set ting provides a perspective that all the documents in the world don’t have.”

The field trips convinced many in Alabama that setting up a community system requires more than money — it requires careful planning that includes people who will be directly affected by the system.

“Not having had the services available has been a deplorable situation for Alabama families,” said Rogene Parris, director of the Alabama Alliance for the Mentally Ill, who has been helping to plan community services. “People say that in the deep Southern states nothing is going on positively. Well, I say just watch us.”

With the Wyatt Committee and community advocates pushing for change, Alabama now has a comprehensive plan to set up local crisis centers, transitional and group homes, and other community-based support services for the mentally ill.

“The plan is now in effect,” said Kathy Sawyer, Alabama director of advocacy services and a member of the Wyatt Committee. “It’s being funded. Facilities are now being leased and constructed.”

Power in Numbers

Perhaps most surprising of all, the state is actually pumping money into the system to pay for new community services. The department of mental health received a 20 percent increase in its budget last year for community spending, and Governor Guy Hunt signed a bill in May 1988 allowing the department to issue $100 million in bonds. So far, the department has issued $60 million — half for community services and half for state institutions.

The bond issue was the result of intense lobbying by both mental health advocates and officials within the system. Charles Fettner, director of Bryce Hospital, pushed hard to convince the state to spend enough money to tear down parts of the 108-year-old hospital and build new facilities. Without the construction, he said, Bryce will be unable to maintain its accreditation as required by the 1986 Wyatt settlement.

“Changes at Bryce required political planning, not just a dream,” Fettner said. “We sold the bond issue to the legislature.”

Before Fettner took over as director of Bryce in 1981, there had been eight directors in the nine years following the Wyatt decision. Unlike most of his predecessors, Fettner is a lawyer, not a psychiatrist. His favorite subject seems to be the architectural blueprints and color-coded charts of proposed construction that clutter his office at Bryce.

“We hope we’ll have political leadership that recognizes the needs of the mentally ill — not because some judge is telling us to,” Fettner said.

Rogene Parris, director of the state Alliance of the Mentally Ill, also lobbied for the bond issue. The mother of a son with schizophrenia, she has helped AMI grow from a small support group to a statewide organization of more than 1,000 families. The group held three rallies on the steps of the State House during the last days of the 1988 session to urge the legislature to approve the bond issue.

Parris knows her group’s political power lies not in cozying up to politicians, but in numbers. “It shouldn’t matter who is governor,” she said. “Any governor should be putting the disabled ahead of politics.”

Perhaps the greatest success of Wyatt has been in giving advocacy groups across the country a lesson in the politics of mental health. Lawyers on the Alabama case went on to other big institutional lawsuits, using Wyatt as a precedent to spur other states to improve community services and conditions in state mental hospitals.

“States were very concerned about the litigation,” says Phil Leaf, director of the Center for Health, Policy and Research at the Yale University School of Medicine. “They asked themselves, ‘How faraway are we from these standards?’”

In fact, Leaf said, Wyatt had a much more immediate effect on states outside of Alabama that were worried about lawsuits. “They focused on their level of funding and how it affected hospital staffing and individualized treatment plans,” Leaf said. “There was a lot of action around the country as a result of Wyatt.”

Advocates like Leaf say that experiences in other states prove that even patients with the most severe mental illnesses can benefit from a return to the community. The task in Alabama is to build a system that will make that happen.

With advocates like Rogene Parris and David Marshall hounding state officials, change is certain to continue. “I believe in going to the powers that be,” said Parris. “They either produce or let’s get someone new.”

David Marshall agreed. “I start out with the attitude that there’s no excuse, and I don’t want to hear it,” he said. “I want it changed.”

Tags

Grace Nordhoff

Grace Nordhoff is a graduate student in social work at the University of North Carolina. (1989)