Inside Looking Out: Introduction

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 3, "Inside Looking Out." Find more from that issue here.

Painful images of “mentally ill” people confront us every day. TV evangelist Jim Bakker has a nervous breakdown. He is manacled and driven away, disheveled and sobbing, to a mental institution. Talk show host Oprah Winfrey does a program on “Paranoid Schizophrenics Who Kill.” She cries as she listens to a woman describe how her husband incinerated their two children. A “severely disturbed” man in Louisville opens fire on his co-workers with an AK-47 attack rifle. He kills seven and injures 13 before taking his own life.

The South has a particular history of — and fascination with — images of madness. The crazy cousin who thinks he’s Stonewall Jackson, the grandfather who has a habit of bursting into the parlor stark naked, the charmingly “eccentric” aunt who talks to imaginary friends — all are firmly rooted in the myth and folklore of the region. The topic of insanity also figures prominently in Southern literature, from Boo Radley in To Kill a Mockingbird to Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire.

The myth and literature have their roots in stories that are all too real. Like a girl we know of who walked home from school to find her mother gone. “She’ll come back someday soon, don’t you worry,” the girl was told. She never learned that her mother was sent away to a mental hospital, severely depressed.

Or the parents who couldn’t understand why their college-age son was obsessed with a rock star and refused to come out of his room. Eventually, they had him committed to a mental hospital, fearing he might have schizophrenia. The neighbors watched from behind their curtains as the sheriff came to take the young man away.

Such stories stir something deep inside us. They remind us that the line between “us” and “them” is precarious at best — that we are lucky if we have never experienced serious abuse at some time in our lives, if the biochemistry in our brains seems balanced, if we manage to live through a nagging depression or don’t flip out when things get too stressful.

Yet whether we realize it or not, we all have friends or family who have entered the mental health system looking for help. Studies show that one out of every five Americans has been diagnosed with mental illness. Many belong to what mental health professionals call “the worried well,” people who seek advice from therapists. Some simply crack under the pressure of daily life and spend a few months in a psychiatric ward. Others have lifelong illnesses, like schizophrenia or manic-depression, that permanently alter their minds, bodies, and spirits.

The mental health system has worked for some people — especially those with the resources to harness its expertise. But as the stories in this cover section of Southern Exposure show, the system often serves as little more than a dumping ground for anyone society doesn’t want or doesn’t like. Blacks get carted off to mental hospitals at a higher rate than whites. Teenagers troubled by the world they live in are sent away to private psychiatric hospitals. Elderly residents are stuck in adult homes, small facilities that are fast becoming a big business.

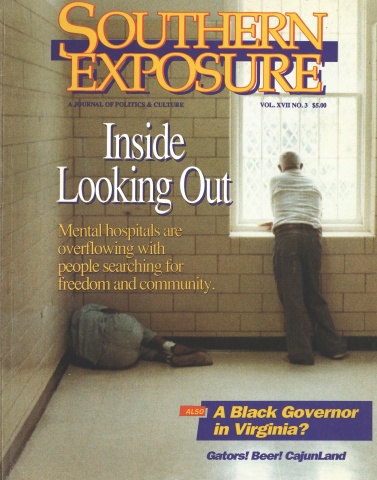

The South has never been known for its humane care of the mentally ill. Southern states were slow to follow the rest of the nation in letting mental patients return to their communities, and decent mental health care still exists only in selected pockets of the region. Big mental hospitals remain the main destination for most people diagnosed with serious mental disorders, yet those hospitals remain colorless and confining, and offer little in the way of treatment.

The lives of many Southerners have been inextricably altered by their experiences in mental hospitals. Some are still on the inside, looking out. Others are struggling to survive in communities across the South. A few are even beginning to shape new identities as mental health “consumers” and to forge new alliances of ex-patients. Their advocacy efforts prove that there are few of us — no matter how serious our “illness” — who do not heal better with healthy doses of freedom and community.

Like Atticus Finch, whose daughter’s life was saved by Boo Radley in To Kill a Mockingbird, too few of us recognize the silent role our mentally ill neighbors play in our own lives. And like Blanche DuBois, committed to a mental hospital at the conclusion of A Streetcar Named Desire, too many of us have been forced to depend on the kindness of strangers.

Tags

Grace Nordhoff

Grace Nordhoff is a graduate student in social work at the University of North Carolina. (1989)

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.