“I Finally Got Out”

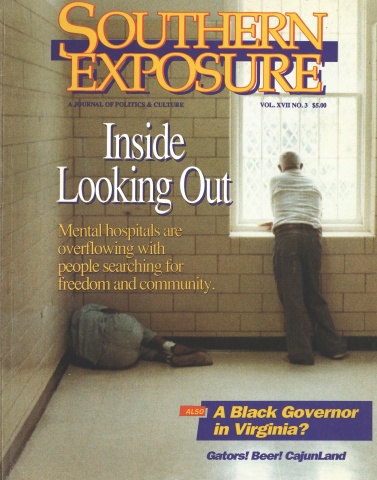

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 3, "Inside Looking Out." Find more from that issue here.

Anita Courtney describes herself as a “mental health systems survivor.” At age 16, confused and saddened by her mother's death, she was placed in a private mental hospital, drugged, and given shock treatments.

Today, 16 years later, Courtney frequently speaks about her experience at schools and churches near her home in Lexington, Kentucky, hoping to warn others of the dangers of mental hospitals. She also participates in co-counseling, an alternative counseling network that emphasizes emotional expression over drug treatment.

It started when I was 12. We found out my mom had cancer. For the next four years she just got sicker and sicker. She ended her life in a nursing home, on morphine, bald, blind, covered with bedsores and weighed about 80 pounds. It was awful.

I spent a lot of time with her during all of that. I would go to school during the day like a regular teenager and then spend the rest of the day in the nursing home with her. Everybody was so impressed that I was such a trouper, that this young girl was taking care of her mother. And then she died.

The whole thing was really hard on me because as the youngest child I was very close to her. She gave me unconditional love and looked out for me, so it was devastating to have her get sick and go through all that.

A few months after she died, I just got terrified. I’d never felt anything like it; I was really scared. I started to think a whole lot about why we are on this earth, the meaning of life. It seemed to take up all of my attention.

I told my dad how I was feeling, and it was hard for him to see his daughter with all these emotions. I don’t mean to badmouth him in any way. I just think he didn’t have a clue of what to do with me. So he said, “Well, let’s go see the family doctor tomorrow.”

My doctor said, “This isn’t normal.” He gave me a prescription and made an appointment for me to see a psychiatrist. So I told the psychiatrist, “I feel really scared, I’m wondering about the meaning of life and death.” And he said, “That’s not normal. You need to go into a mental hospital.”

So a few days later I was put into a place called Our Lady of Peace, which I always think was a great name for a mental hospital. It was a joke among the people in the hospital — “Where is she? Has anybody seen her? Where is this Lady of Peace?”

But I remember being scared and not wanting to go in.

I got put on the fourth floor of Our Lady of Peace, which is a private facility in Louisville, very posh — swimming pool, tennis courts, bowling alley, crafts, cafeteria. It was a pretty nice place. My dad’s insurance paid for it.

I was put on Thorazine and Stelazine, which are heavy-duty drugs. I was so overdrugged for the first week that I would just shuffle around. Drugs like that glaze you over and make you real fuzzy and tired. Physically and mentally I felt awful.

My psychiatrist was not very helpful at all. He said my problem was that I wanted to sleep with my father. My mother had just died, and he made it into this sexual thing.

I only spent about five minutes with him a day. I’d be in the hall and he’d come up and say, “How are you, honey?” And I’d say, “Oh, I feel awful.” And he’d say, “Well, I’ll see you tomorrow.” And then I’d get a half-hour session once a week. I think there’s an idea that when you go into a hospital you’re going to get all this care, but in fact they don’t have enough staff in those places, and you end up getting very little attention.

It got weirder and weirder as I went on. I remember one session he said, “Who is your prettiest girlfriend?” This was the kind of ‘useful’ stuff we’d do. I would always fight him, and he’d badger me. He’d say, “Okay, now I want you to imagine making love to her and tell me what it would be like.” He was always wanting me to sit on his lap. I mean, here I am, 16 years old, trying to deal with my mother’s death, and he’s doing all this weird stuff.

Every time I tried to fight back and stand up for myself, he would say, “Who’s the patient? Who’s the patient?” He’d ask the question about six times and finally I’d just get sick of hearing him and I’d say, “I am.” He’d say, “Who’s the doctor? Who’s the doctor?” And I’d finally say, “You are.” It was a real power struggle.

This kind of horrible counseling went on for three or four months. I wasn’t feeling any better, and he finally said, “Well, I think you need shock treatments.” I said, “No way, I don’t want them.” I remember fighting that a lot. But he had so much more power in the situation that I didn’t have very much choice.

My whole family felt uncomfortable with him, but we had no clue as to what to do. He was the expert, even though all this bad stuff was going on. He had hung a shingle out that said, “I am Dr. O’Connor, I am a psychiatrist. I know how to help people who are struggling with their emotions.” We all believed him. We were the typical middle-class Americans — you put your faith in the medical establishment. He did a great sales job about how the shock treatments would “cure” me. We got talked into it, even though our best instincts told us differently.

So I started getting the shock treatments, and outside of my mother’s death they are the worst thing I’ve ever been through. God! They were physically and emotionally torturous — that’s the word I would use. I can remember being terrified the night before having them.

What happens is you get up and you leave your nightgown on and sit around by yourself and wait. An aide would give me a shot that would dry out my mouth, which was extremely uncomfortable. I guess they don’t want you choking when you go through the convulsions. Then someone would take you down to the waiting area, and then you’d have another wait. And then you finally get rolled in to get your shock treatments. It was a long morning of dread.

I can remember every single time before I was going to get them, I’d say to the doctor, “I do not want these.” The way I understand the legalities of it, if you say you don’t want them, you shouldn’t have to get them. He’d respond by saying, ‘‘Oh, you’re just afraid we’re gonna look up your robe.” He’d say all this sexual stuff. Then he’d give me general anesthesia, which I hated because I was already so drugged.

What they do is they put electrodes to your head, and then they put between 75 and 150 volts through your brain to put you through a convulsion. The next thing I know, I’d wake up feeling very disoriented, with a pounding headache, and I couldn’t think. For someone who’s been told that they’re “mentally ill,” not being able to think is no fun.

After about two days, I’d start to feel somewhat like myself again. The anesthesia and some of the physical effects of the shock would start to wear off — and then I’d get another shock treatment. I got them every two or three days for about a month, so I could never come out of the zombie state. I got so I couldn’t look at myself in the mirror anymore, because I didn’t look like myself anymore. I was just glazed over.

After every treatment he would say, “How do you feel?” And I’d say, “God, I feel awful, just awful.” What I finally realized was that as long as I said I felt bad, I kept getting them because he thought that meant I needed more treatment. So the next time I said, “I feel much better now,” lying through my teeth, because the more I got, the worse I felt. He said, “Oh, maybe we’ll be able to stop these soon.” After the next one I said, “I feel great!” And then he stopped them. That was what all the patients around the hospital taught each other — that if you wanted to stop getting these things, don’t say how bad you feel, say how good you feel. Then they’ll think they’re working and they’ll leave you alone.

I still have shock treatment nightmares, where there’s like this explosion going off in my brain and I can’t wake up. I keep trying to wake up, but I can’t. It’s a very physical dream.

The one nice part of the whole experience is that I made wonderful friends. Some of the other patients were some of the nicest people I ever met in my life, the most fun and creative. We had a good time goofing off, laughing and talking. That was what saved me — it wasn’t like I got any help from my psychiatrist at all.

It was interesting, too — they all had a story to tell of some way they’d been hurt dramatically before they got in there. One woman’s husband was beating her a lot. Another girl’s dad had been sexually molesting her. There was a nun put in there because she was angry about the sexism in the Catholic Church. People had gone through hard times, and they got called “mentally ill” for it. It made them feel bad about themselves, and that what they had gone through was somehow their fault.

I finally got out. I was in the hospital for five months. And I felt so much worse when I got out than I had when I went in, because I had gotten all these bad messages about myself, plus all the physical stuff that I had been through.

I went back to high school. Interestingly enough, it was a fairly common thing for people in my high school to go into that mental hospital. When I was in I think there were four other kids from my high school in there.

The doctor still wanted me to stay on these drugs. He said, “If you don’t stay on these drugs, you will really go crazy.” Even though I felt awful on the drugs — I was tired, I couldn’t concentrate — he had me living under such fear that I felt like if I didn’t take them I would fall apart.

The interesting thing was, when I finally quit taking the drugs a year later, I started to feel much better. I quit thinking about, “Why are we on this earth?” I got back to myself and I started feeling much better and I did fine.

I felt like I was trying to deal with my mother’s death, and I just took this huge detour. I was looking for help, but I got hurt instead. Then I came back out, back from this very wrong turn.

I got involved in something called co-counseling, where two people take turns listening to each other. One person can’t have such power over another. It’s an equal relationship.

Co-counseling help me realize that I didn’t cry or grieve very much when my mother died. Since then, what I have done is spend a lot of time crying for her loss and for all that I went through, and that’s what’s healed me.

I talked about it at every co-counseling session for four years. I’ve done a lot of crying and raving and talking and shaking about all of this. It’s helped a lot to vent about all that happened. If I didn’t have co-counseling, I don’t think I ever would have started talking about it among my friends and to society.

This lecture circuit I’ve gone on, it’s really hard to stand up in front of large groups of people and tell this story. It’s pretty scary, but I don’t want anyone else to go through what I went through. I always think, God, I wish when I was 16 years old there had been someone out there saying, “Shock treatments may harm you more than actually help you.”

At a talk I gave a while back, a guy who was there said they were getting ready to give his niece shock treatments. He went and called his sister and said, “I heard this woman speak and she said that they didn’t help her, they only made things worse.” And his niece didn’t get them.

There is a lot of literature that says, “Shock treatments cure people,” but I think it just makes troublemakers real docile and quiet and cooperative. It may look like they’ve improved on the psychiatric charts, but inside they’re really struggling. You can do the same thing with a child — you can beat the shit out of them and they’ll act like you want them to, but it doesn’t put them in any better position.

If people ask my advice about seeing a psychiatrist, I say be very careful. Really pay attention to your own instincts. What you’ll need more than anything is to get to talk and cry about it, and if you’re getting drugged up that’s going to interfere. In my mind, people cry because they need to be healed, not because they need to be drugged, to have it turned off. When I was trying to deal with my mom’s death, the drugs put a big roadblock in the way.

I feel confident now that I will never get in that situation again because I have so much support. I have a much better sense of how to handle hard times. I have a much better sense about what an “expert” is. I know what I need for myself most of the time.

Tags

Grace Nordhoff

Grace Nordhoff is a graduate student in social work at the University of North Carolina. (1989)

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.