This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 3, "Inside Looking Out." Find more from that issue here.

“One day there was a person down here who wanted to die. She didn’t want to go to the hospital, but I called 911. And we made arrangements for someone to pick up her son at school. The police and the ambulance came. I told the police officers it was a possible overdose. She had two bottles of medication, and she took five more pills than she was supposed to take in one hour. They took her to Central State, but she got out.

“I was really shook up. That was the first time I ever saved somebody’s life after being suicidal myself. I tried to commit suicide about 25 times in my past life. I took all my anti-depressant pills. I tried to cut my wrists. It started when I was 16 or 17, when I was raped by my brother.

“Sometimes I couldn’t handle life. Part of me wants to die, and part of me wants to live. I fight it every day. About two years ago I was in the cardiac care unit with two heart attacks. I was very down, in the lowest depression you can possibly go to.

“If it weren’t for the Drop-In Center, I’d probably still be there. Coming down here and doing all this work brings me up again. As long as I’m busy, I’m happy. I still have a lot of work to do on this earth before I go.”

— Jack Parker

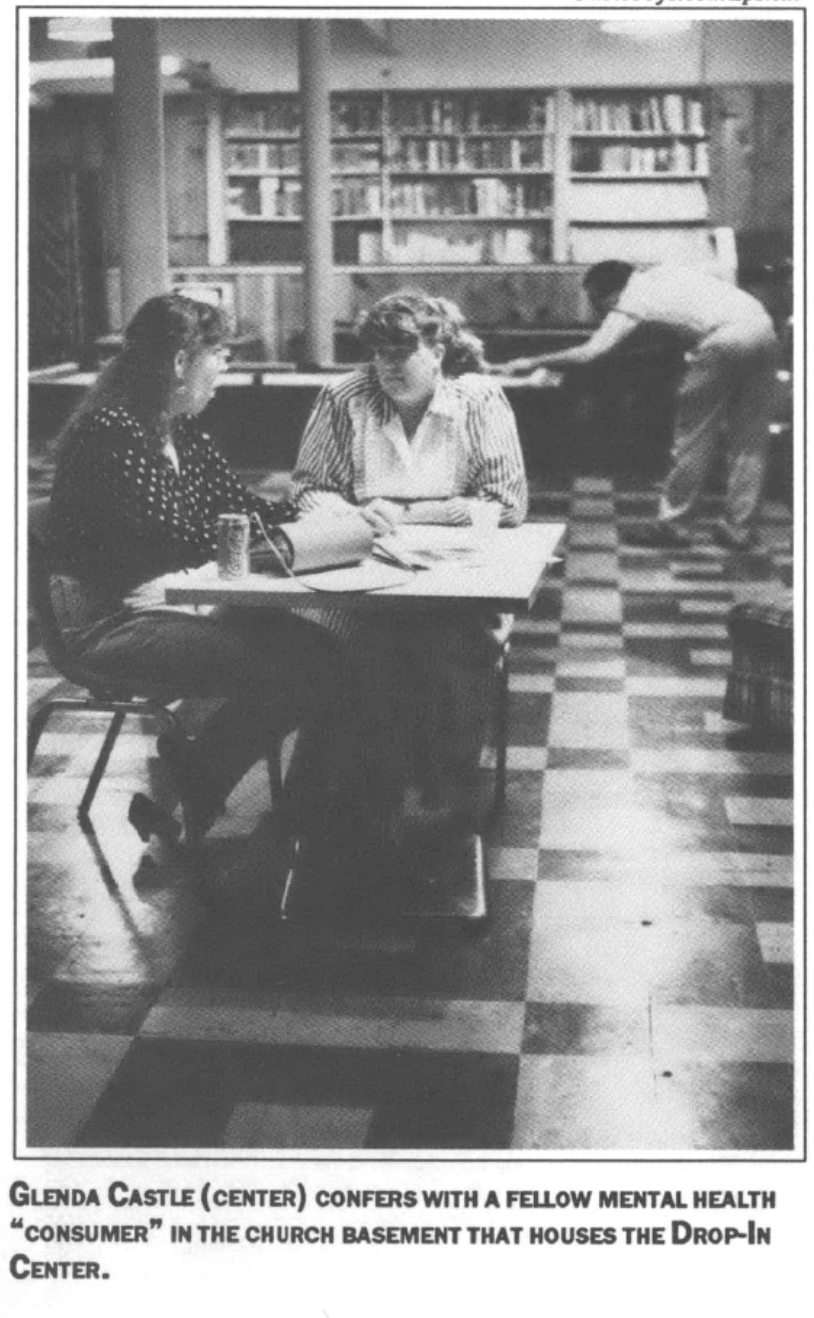

Louisville, Ky. — In many ways, the Downtown Drop-In Social Center looks like any other gathering place in a church basement. People come and go, sipping coffee, shooting pool, talking in small groups. There are some books and a computer and a few sofas in front of a television set. Near the door, there’s a little area that doubles as a kitchen and an office.

But there are two things about the Downtown Drop-In Center that set it apart from any other community center in the South. Most of the folks here have been hospitalized for mental illness at least once — and they run the center themselves, with no staff psychiatrists, psychologists, or social workers.

Working together, a handful of men and women at the Drop-In Center have placed themselves at the forefront of a nationwide “consumer” movement for decent mental health care. They have shunned terms like “mental patient” or “client,” working instead to empower mentally ill consumers to participate in their own care and to take responsibility for themselves and each other.

“We are a civil rights movement,” said John Basham, a state advocate for the mentally ill and a mental health consumer. “We are as much a civil rights movement as the movements of the ’60s. People always say, ‘What do consumers want?’ Consumers want jobs. Consumers want education. Consumers want the same things everyone else wants. It’s just a whole lot harder to get them when you got that psychological label hanging over you.”

Basham, a Vietnam veteran diagnosed with manic depression, serves as director of a statewide consumer group known as ATAK/MI — Advocates Taking Action in Kentucky Against Mental Illness. The year-old group is headquartered at the Drop-In Center, which also serves as home to the Consumer’s Gazette, a monthly newsletter published by Jack Parker.

But first and foremost, consumers say, the Drop-In Center provides a place for those with severe, long-term mental illnesses to be who they are, untroubled by the stigmas they encounter everywhere else. Many who come to the center are poor or homeless. They help each other find food, clothing, housing, and jobs. They counsel each other, read up on their diagnoses, learn about their legal rights, and sometimes form lasting friendships. Some even try their wings at volunteering for the center, eventually seeking further education or employment.

“If you want to sit here and talk to the wall, you can come and sit and talk to the wall,” said Glenda Castle, coordinator of the center and president of ATAK/MI. “People accept you. Everybody needs a place where they can be themselves. You don’t have to wear a facade, and that’s why friendships work.”

Castle, a talented and energetic woman of 39 and the mother of four children, saw 47 professionals — public, private, and theological — before she was finally diagnosed with multiple personality disorder, a mental illness that generally affects those who were physically or sexually abused as children.

“There’s a sense of empowerment people get by being who they are while they’re here,” Castle said. “No one is here to diagnose them, to treat them. It gives them someplace they feel they’re safe. What makes it different is we’re not governed by professionals. The people who use it run it.”

Coffee and Self-Respect

The Drop-In Center opened in 1984 and moved to its present location in the basement of an Episcopal church two years ago. Castle was hired as part-time coordinator by Seven Counties Services, a non-profit agency that contracts with the state to provide community mental health services to 3,000 people in the Louisville area. The center scrapes by on a budget of $10,000 a year, including Castle’s meager salary of $5 an hour.

Most Drop-In Center members are referred by Seven Counties staff, but some simply walk in off the street. Between April and June alone, consumers signed in on the center’s clipboard 1,794 times. More than 650 consumers used the center for the first time during the past year.

The center is basically one long room with a checked floor, a pool table, a piano, and some furniture. Members keep it running by answering the phones, cleaning up, producing the newsletter, and selling coffee and soda to pay the phone bills. They also serve on local and state advisory boards, attend national conferences, and run a consumer job pool.

Castle said the center got started because several Seven Counties professionals recognized the importance of the consumer movement and managed to get [words missing].

“Our area is probably more progressive than any area in the state,” she said. “We’ve been fortunate here in Kentucky that we’ve had people willing to work with consumers, to bend, to allow them to do things other states wouldn’t be willing to.”

Castle’s supervisor at Seven Counties is Theresa Watson, a psychiatric nurse who works with the homeless mentally ill. “As an agency we’re moving in the direction of more consumer-driven treatments,” Watson said. “Because who else has the answers? We don’t. We’re so primitive in what we know about the brain.”

At first, Seven Counties hired a professional to coordinate the center, but Watson called the experience “disastrous.” Too often, she said, professionals find it difficult to work with consumers without taking on too much responsibility — and thus taking power away from the very people they are trying to help.

Watson said it would be hard for her to work with consumers at the center the way Castle does. “If I wasn’t careful, I’d get into a counseling role because of their expectation that I’d solve their problems,” she said. “I don’t even know the subtle ways I disempower people.

“A person like Glenda — who’s been there — is much more tuned in. She can challenge people to do better as a peer, not a professional with a treatment plan,’’ Watson added.

Dale Bond, director of adult services at Seven Counties, agreed. Consumers “believe their own more than they believe us,” he said. “In a way we’re the oppressors telling them what to do.”

Most “clubhouses” run by professionals have strict rules requiring consumers to attend regularly, participate in therapy, and remain on their prescribed medication. Bond said that when he got the idea for a consumer-run center at a national workshop several years ago, he envisioned a place that would give consumers greater freedom in their daily lives.

“These are folks who tend to be withdrawn, dependent. They’re told they have severe problems. Everything is telling them they’re not capable. Professionals until very recently told them and their parents not to expect much. Society was very unaccepting. If you got kind of bizarre, we’d put you away and that was it,” Bond said.

“We want to spark some basic self-respect and hope. Hope is what keeps most people going. And that’s what they tend to be very short on.”

Referring someone to the Drop-In Center is a little like “throwing somebody into a swimming pool,” Bond said. “If no one plans any activities, there are no activities. They see others with just as bizarre thinking processes and behavior doing things, socializing, taking the initiative, making things happen . . . and they decide maybe they can, too.”

Off the Streets

Hugh Kennedy is one consumer who decided to help make things happen at the Drop-In Center. Working as a volunteer, he said, makes it less likely that he will “go home and shut the door and stay put. Instead of closing in, I come here for support. If this wasn’t here, I don’t know of any place I’d feel comfortable going. Down here nobody cares if you’ve been sick last week. They welcome you back. You’re not ‘forever ill’ as society puts it.”

For consumers coming out of mental hospitals, especially those who are poor or have never held jobs, there are few non-clinical settings to turn to. Many feel like outsiders, and are unlikely to be drawn to churches, malls, or athletic centers. After months or perhaps years of having others make all their decisions for them, they suddenly find themselves on their own.

Joe Wise, a tall, mohawked young man who is quick to joke, got into lots of trouble before discovering the Drop-In Center. Now he’s been clean and sober for five weeks, he said. A week ago he found a place to live after being homeless for three and half years. And he plans to join the Marines.

Before he found the Drop-In Center, he hung out in bars, often getting into fights. “My nose has been broken four times.” He also got himself permanently barred from a day treatment program. But at the center, he said, “drinking is not allowed. Most of the time that’s what’s causing a fight.”

The center “helped me to get my nerves calmed down,” he said. “It gives me more time to think in a quiet atmosphere, instead of bars, which aren’t very quiet.”

For two hours, three days a week, Wise sweeps the floor, makes coffee, and empties ash trays. Volunteering at the center “gives me some responsibility, some way to grow up,” he said. “It’s like a job. It’s a thing I have to do to stay in the Drop-In Center.”

Wise almost lost that chance, too. After breaking too many center rules he was barred for 30 days. He would have been barred for 90 had he not negotiated for probation.

“I wrote out the contract and we all signed it. If I come in drunk or high, use too much vulgar language, or treat anyone with no respect, I could get banned indefinitely,” he said. “I don’t want to get barred out. That would ruin everything again.”

Wise said that when he has a problem, he can usually find someone to talk to at the center. “We talk three to four hours at a time about problems we have in common and work out ways to deal with them. We set goals.”

His own goal, he said, is to “get off the streets and stay off the streets. And to choose something I can look forward to, something in my future.”

More Than Advice

For people who are hearing voices or experiencing multiple personalities, consumers at the center say, something as simple as being able to talk to other people and make friends can be a life-changing experience.

“For me, treatment or therapy comes from within a person,” Castle said. “If people have an opportunity to talk, they can work things out themselves. And that’s what we try to do here. If someone wants to talk, there’s someone to listen.”

Castle recently arrived at the Drop-In Center early, around eight a.m., to catch up on some work. Instead, she got into a conversation with two members who showed up.

“A guy who was wandering around because he couldn’t sleep saw the light on and came in,” she explained. “We spoke about school. He wants to go back to college, and his therapist is dragging her feet, saying he should work for a year first. We encouraged him. We said if this is what he wants to do, go for it We told him there’s financial aid available. So he went and got the application and filled it out and will be taking two fall classes. He’ll start going regularly in the spring, studying sociology and anthropology.”

But consumers find more than helpful advice at the center — they also find work. One of the most successful and innovative programs that members have initiated is a job pool. Any member who volunteers at the center on a regular basis is eligible after two months. Jobs range from contracting with a case manager to help a newly released consumer learn how to ride the bus or find affordable housing, to mowing lawns and doing clerical work. Consumers receive $3.75 an hour, paid by Seven Counties.

The job pool offers many consumers the first chance to earn money on their own. Hugh Kennedy works for the job pool keeping track of other participants. “It makes me feel like I’m accomplishing something,” he said. “It keeps me in the mainstream.”

His therapist told him to keep busy, Kennedy said. “Until I did, I stayed sick. I’ve had friends here push me . . . to start to get back into the swing of things as far as society goes. It’s helped me a lot.”

Like other consumers, Kennedy has found it almost impossible to find a regular job. “They want to know where those four years went. And if you say you had depression problems, that’s it.”

The center often comes up with creative ways for members to work. With help from Castle, for example, Jack Parker wrote a grant proposal and got $3,000 from the National Institute for Mental Health to start the Consumer Gazette.

“I wrote the whole mess out myself. I felt great,” he said. “My goal is to inform as many mental health consumers in the state of Kentucky as possible about what is really going on.”

Castle said the job pool helps everyone, especially when it involves consumers helping social workers assist other consumers. “The case manager is not as overloaded. The patient is meeting another person like themselves and developing a healthy relationship with somebody other than their case manager. The consumer is building self-esteem and showing that they have something to offer.”

Watson, the psychiatric nurse, also praised the job program. “They’re not doing busy work. They’re doing solid, important work,” she said. “I believe in it, and I am still amazed at what incredible potential people have.”

Coming of Age

Consumers are also able to employ themselves. Connie Starcher has a part-time job as coordinator of ATAK/MI, the grassroots consumer group. She is setting up a speakers bureau of professionals and consumers willing to talk about mental health issues, and is planning a fall conference.

“I love working here because I think the community needs to know that people with mental problems or emotional problems have talents to offer,” she said. “They can be successful if given the proper therapy and treatment. We can be well educated, and we can function as viable parts of society.”

Founded by 50 Kentucky consumers and ex-patients late last year, ATAK/MI is already working to create more drop-in centers and consumer-oriented clubhouses and to advocate better housing, jobs, and education by and for the mentally ill.

The group’s purpose, as stated in its bylaws, includes “the promotion and self-determination among mental health clients and the advocation of client dignity, community integration without discrimination, and freedom of choice on behalf of mental health clients through public education.”

As is evident from its acronym, ATAK/MI doesn’t stick to safe issues.

The group had its first major confrontation with the state last July when members planned a conference and invited two prominent critics of conventional psychiatry to speak — former psychoanalyst Jeffrey Masson and Dr. Peter Bregin, who had voiced opposition to electroshock and drug therapy on the Oprah Winfrey television show. When federal officials learned of the plans, they directed the state to withdraw binding for the conference.

ATAK/MI officers blasted the move as censorship and said the state had undercut their goal of allowing consumers to make their own decisions. But they cancelled the conference, afraid it would jeopardize federal funds the group relies on.

Bond, the Seven Counties psychologist, said he was surprised by the formation of ATAK/MI and its openly political agenda. “I did not predict or expect this ATAK/MI type of a movement. It’s out of our typical framework. Though I had some progressive ideas, it wasn’t part of our professional culture. No one taught me about it in school.”

Bond said the group could have an impact on decision-making in the mental health community, “if we’re comfortable giving them a shot.” The consumer movement seems to be “coming of age,” he noted, saying consumers he meets at national conferences “seem to have specific, positive strategies to bring about change.”

Yet some professionals remain skeptical about consumers in ATAK/MI, Bond said. “They think they’ll get in over their heads and hurt themselves.” For example, the group has taken a fairly strong stand against electroshock treatment, even though most professionals insist that a small number of extremely withdrawn consumers could be helped by it.

Many politicians outside the mental health community also refuse to take ATAK/MI seriously. Bond predicted there will be “reticence about accepting them as a legitimate group because they don’t think the way the rest of the world does.”

John Basham, the director of ATAK/ MI, said many mental health professionals miss the point of the consumer movement. “For many people I work with, the movement is a good idea,” he said. “To me it means much more. It means pride.”

Basham acknowledged that consumers who gain more freedom through the movement may make some wrong decisions at first — but that, he said, is an essential step on the road to independence.

“Empowerment means allowing people to learn by a natural process,” he said. “Maybe the first time you give them their social security check, they’ll blow it, but that’s how people learn — by mistakes.”

Tags

Robin Epstein

Robin Epstein is a freelance writer in Louisville. (1991)