This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 3, "Inside Looking Out." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-gay slurs.

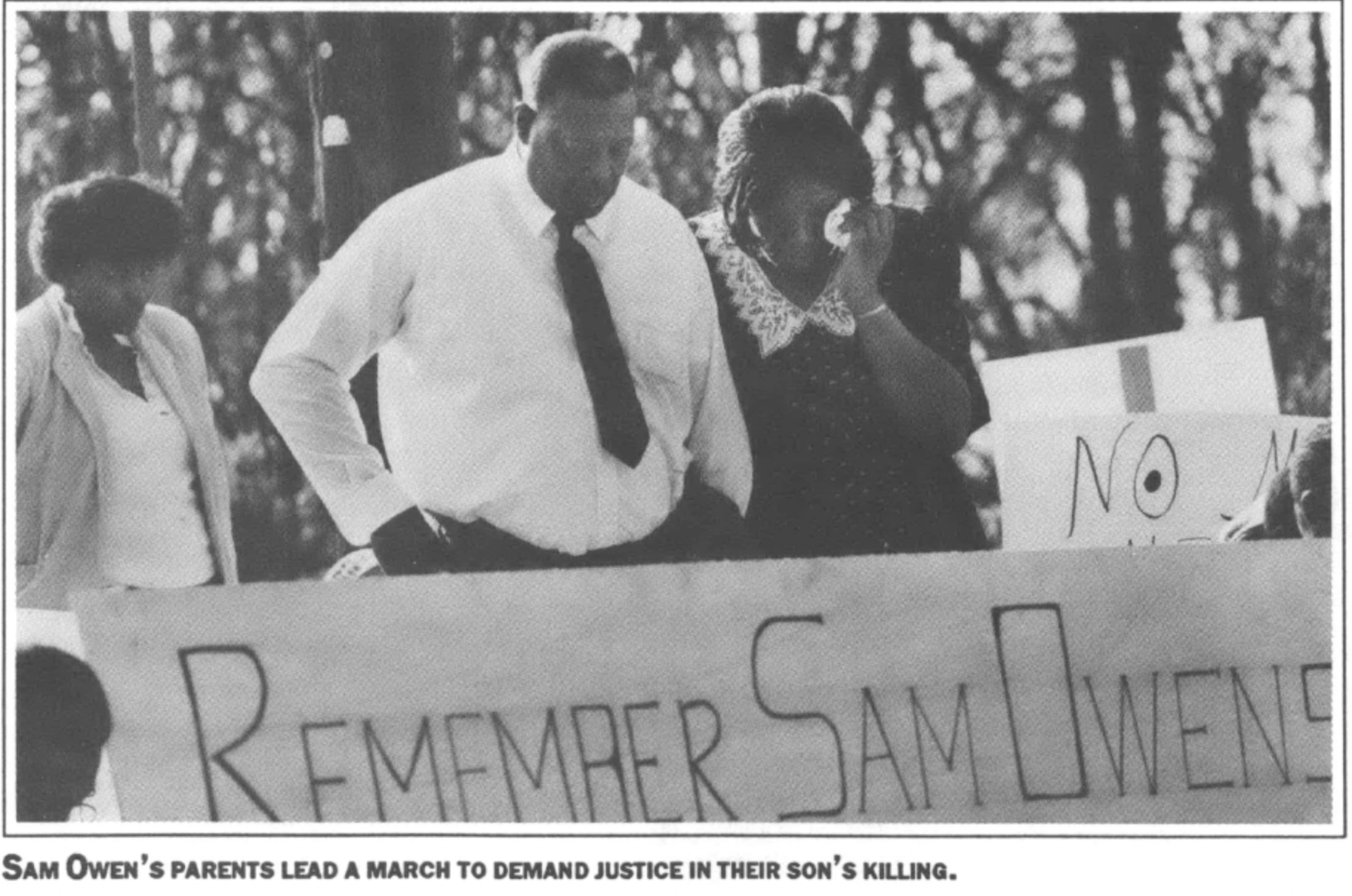

Winnsboro, S.C. — Nearly 1,000 people marched down Congress Street, moving slowly but deliberately. Many carried homemade signs. They were headed for the sheriff s department.

When they got there, they found the doors locked. Sheriff LeRoy “Bubba” Montgomery was gone.

Kamau Marcharia, a local community leader, shook his head sadly. “Evil flees in the face of righteousness,” he said. The group prayed in the parking lot, and then moved on to the county courthouse. Marcharia stood on the steps and addressed the crowd.

“The fact that everyone is here today says ‘no’ to the plantation mentality,” he said. “We are here to show that you cannot shoot black people and drag them through the woods like animals.”

A few people watched from the sidewalk in silence. They had never seen anything like it before. Winnsboro is a town of fewer than 3,000 people, yet here were hundreds of ministers, grocers, factory workers, homemakers, anti-nuclear activists, grandparents — all rallying together under a single banner.

The banner bore the name of a young man with a history of mental illness who had been shot dead by a sheriff s deputy. The banner read, “Remember Sam Owens.”

Going Crazy

Henry Owens remembers the night his son died. It was the evening of January 5, 1989. The family was at home, and Sammy was out in the woods, inhaling gasoline fumes from a plastic milk jug.

“He was sniffing gas, and some of the little grandboys were throwing rocks at him,” Henry recalled. “That’s when he got upset. If you say anything to him or throw a rock at him or something like that, then he just goes crazy.”

Sam grabbed an ax and started to knock the awning off the front porch. “He told me he’d kill me,” his father said. “He don’t know me from anybody when he get like that.”

Sammy got like that a lot. He had been sniffing gas since he was 10, and had dropped out of school a few years later. At age 25, addicted to the gas fumes and unable to find work, he often sat around the house all day, depressed and bored. The gas made him wild, drove him into a frenzy if provoked. His family had learned to steer clear of him — and to call the police to take him to the state mental hospital in Columbia when he got violent.

“He been back and forth to Columbia 40 or 50 times,” said his sister Mary. “We asked them to keep him a while and maybe he would get better, but once he got off the gas they said there was no reason to keep him and they would let him go. Then he would be back on it. He would go off to that area in the woods with his gas jug and you could hear him out there hollering and yelling.”

On that January evening, as Sam tore up the house with an ax, his sister once again called the police. Sam heard her on the phone, and ran off into the woods behind the house. There, 60 yards into the tangled underbrush, he climbed a cedar tree, the gallon jug in one hand, the ax in the other. It was growing dark.

The Killing Tree

Deputy sheriffs arrived minutes later, and Henry Owens led them into the woods. “I tried to get Sammy down out of the tree,” Owens recalled. “He was cussing so much, I just come on back to the house.”

When the family heard shouting in the woods, Owens sent his oldest sons, David and Alphonso, to see what was happening. When they got there, the brothers were startled to find seven armed deputies at the bottom of the tree. Sam was surrounded.

Some of the deputies had dealt with Sam before; on one call, it had taken three of them to subdue him. Just a month earlier, he had damaged a highway patrol car with a pipe. Sammy had four outstanding arrest warrants on charges of disorderly conduct and resisting arrest. They knew he was addicted to gas fumes, and they knew he had a history of mental illness.

Yet instead of trying to calm Sam down, deputies began to taunt him. David and Alphonso stood by as deputies called their brother “pussy” and “faggot” and “coward.” The more they jeered, the angrier Sam grew. He shouted back, threatening to kill them. Later he threw the gas jug at them.

For over an hour, deputies circled the tree, shining their flashlights on Sam and calling him names. No one bothered to call the local mental health clinic where Sam went for medicine and counseling, where there were people he knew and trusted, where there were professionals trained in dealing with mental illness.

Finally, enraged and out of gasoline, Sam climbed down out of the tree with his back to the deputies. Nobody moved to grab him, to take the ax away. Instead, the deputies turned and ran.

Sam walked towards them, carrying the ax. Several pulled their guns. Captain Keith Lewis backed into a tree. Another deputy got his foot caught in some old bedsprings rusting in the underbrush. Sam lifted the ax above his head. When he was 16 feet away, Lewis shot him twice with a 9 mm pistol.

The first bullet struck Sam in the groin. The second blast tore through his chest, leaving a two-inch wound in his heart. He spun around and fell to the ground, landing on his back.

Lewis turned to another deputy. “Someone handcuff him,” he said.

“You don’t have to put the cuffs on him,” Alphonso Owens said. “You can see he’s shot.”

A deputy ignored Alphonso and handcuffed Sam. Lewis turned to another deputy. “Mark my spot,” he said.

Then, as family members looked on, deputies took Sam by his jacket collar and pants leg and dragged him through the thick underbrush. As they reached the dirt road by the edge of the woods, Sheriff Montgomery and two paramedics pulled up. Sam was taken to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 7:55 p.m.

Red Eyes, White Lies

Within an hour, state law enforcement agents arrived at the scene and launched an investigation. What they were told did not match up with what eyewitnesses saw.

The paramedics swore to investigators that they, not the deputies, had dragged Sam out of the woods. Deputies said Owens had jumped, not climbed, out of the tree, and had rushed at them with the ax raised. They also said it was too dark to see, even though several gave vivid descriptions of how crazy Owens looked.

“I could really see the white of his eye and right before he come down that tree, his eyes was red,” Lewis said in a sworn statement. “I mean, if the devil has red eyes, he had eyes like the devil.”

A review of the records showed that state agents seemed more intent on clearing the deputies of blame than on finding out whether the killing could have been avoided. On February 6, a month after Owens died, investigators delivered their findings to Sixth Circuit Solicitor John Justice. Justice cleared the deputies of any wrongdoing in the shooting.

Instead, he blamed the state mental hospital in Columbia. “The pity of it all is, Sammy Owens is not alone in the sense that we get these people down there in Columbia, but they don’t keep them,” Justice told a reporter. “I couldn’t count the number of people we have dealt with in court who need long-term and heavy-duty mental health care.”

United Action

Community leaders were outraged. “Perhaps they didn’t do anything illegal,” said Kamau Marcharia. “But it was certainly immoral, and clearly unprofessional.”

Marcharia heads Fairfield United Action, a community group headquartered in Winnsboro. The group was organized to protest the building of a local nuclear power plant in the late 1970s. Since then, it has led voter registration drives, helped fix up low-income housing, and fought for single-district elections to ensure that the county’s black majority of 58 percent is adequately represented in local government.

A few days after Sammy Owens was killed, Marcharia was approached by Charles Sharp, a former police officer, and Coit Washington, a former city councilman. The men decided to call a community meeting to discuss what to do about the shooting. To their surprise, more than 700 people showed up.

“That’s unusual for a rural community,” Marcharia said. “That’s a lot, a lot of people.”

Those who attended formed a new group, Concerned Citizens for a Better Fairfield, and asked Sharp to conduct an independent investigation. Sharp — who spent seven years in the military police and three years as a civilian officer — examined the shooting site and spoke to eyewitnesses who were not interviewed by state investigators.

“The officers just did not know how to handle this individual,” Sharp concluded. “He was a mental patient for six or seven years. They were there for over an hour. They had ample time to contact mental health. This could have been avoided.”

Eleven days after Owens died, leaders of the group met with Sheriff Montgomery and Captain McKinley Weaver of the State Law Enforcement Division. The sheriff admitted that his officers receive no training in dealing with the mentally ill. Asked why deputies taunted Owens, Captain Weaver replied, “We aren’t psychiatrists.” Asked why deputies failed to call mental health officials for help, the sheriffreplied, “I can’t answer that.”

The group demanded that the sheriff suspend Keith Lewis and the other deputies and establish an independent citizens review board. The sheriff refused. On the first Sunday in March, 1,000 people marched on his office. Two months later, hundreds marched past his home. They chanted, “Bubba, Bubba, have you heard? This is not Johannesburg.”

Before long, T-shirts and bumper stickers emblazoned with the words “Remember Sam Owens” were appearing all over Fairfield County.

Blackjack

Winnsboro lies just 20 miles due north of the state capitol at Columbia. Farmers once grew cotton here, but by 1908 the land was the most eroded east of the Mississippi. By 1951, Fairfield was the only county in South Carolina with fewer than 1,600 farmers.

Today there are only two incorporated towns — Winnsboro (population 2,919) and Ridgeway (population 343). The remaining 17,000 people in Fairfield County live in small clusters of homes scattered across the pine-covered countryside.

Henry and Margaret Owens live in a small house next to a church in Blackjack, a tiny settlement about a mile outside Winnsboro. They raised eight children here, including Sammy.

They are now in their sixties.

Sitting in the family living room, the couple described how Sam and his nephew Bob used to spend all week fishing at a nearby pond. One day, when Sam was 19, their boat capsized. Bob couldn’t swim, so Sammy ran a mile for help. By the time he returned, it was too late. Bob had drowned.

“He just went kind of in shock like,” his mother recalled, sitting in the family living room. “He took it hard. He never did get over it.”

“He sure was different after that,” agreed her daughter, Caroline Dorsey. “He would stay shut up in his room by himself. He’d get his jug and sniff gas and talk to himself. He just sort of went out of his mind. . . . He blamed himself for not being able to save Bob. It put a big load on his life.”

Sam knew how to fix anything. He liked to play the guitar, and once in a while he would deejay dances at a local club. After the accident, out of money and desperate for a high, he would go out in the parking lot and suck on the exhaust pipes of cars.

Two years later he made his first trip to State Hospital, the mental facility in Columbia. “They mostly just gave him sleeping medication,” his mother said. “After the accident, he never could sleep.”

Caroline brought out dozens of empty pill bottles and dumped them on the coffee table. “Sometimes he would take pills and sniff gas. Then he’d just go plumb crazy.”

“I just asked them to take him and keep him, but they never listened to me,” Margaret said. “If they had kept him at least six months, he would have been better off. But they never even kept him a month. I thought there was a place where they keep mentally ill children, but they never kept Sam.”

When Sam was home from the hospital, he would visit Mary Green, a therapist at the local mental health center. “She loved him,” his mother said. “She thought a lot of Sam and really tried to help him. She got him on a mobile work crew, and that was taking him away from the gas.”

“We tried to call Mary Green the night he climbed the tree, but we couldn’t reach her,” Caroline added. ‘Those deputies never tried to call her at all.”

Caroline watched that night as deputies dragged Sam’s body out of woods. “They didn’t carry him like he was a wounded person — they carried him like he was a dead animal. They could have helped him, but they never did.”

Her mother began to cry. “I really feel sorry for anyone who has to go through what I went through,” she said. “There’s a lot of families with mentally ill children in Fairfield County. I hope nothing like this ever happens to them.”

Street Talk

Almost seven months after Sam was shot dead, people around Winnsboro are still talking about the killing.

“I think it was wrong to shoot a mental patient like that,” said Earl Bonne, sitting in Heath’s Barber Shop, where he has cut hair for 20 years. “There was enough of them out there that they could have handled him in a more respectful manner instead of shooting him like a rabbit. The police should be trained better to handle stuff like this.”

Out on Congress Street, a young man who asked not to be identified said he knew Sam from State Hospital. “Mentally ill people — these cops take advantage of them,” he said. “Really, nobody can do anything.”

A middle-aged woman in the Fairfield Museum who also asked not to be identified had a different opinion. The killing “may have been justifiable,” she said. “Frankly, there’s been too much attention about this thing, especially the unfavorable newspaper coverage. And then those NAACP marches — I didn’t like those.”

Around the corner in the Launderama on West Liberty, Willie Mae Robinson was washing her clothes. “They didn’t keep him long enough in State Hospital,” she said. “You can’t stay in three weeks and expect to get better.”

“I got a cousin who acts out,” she added. “They wish he could stay in the hospital longer. If they could sign him in for six or nine months, maybe he would get better. But two or three weeks isn’t going to help anybody.”

Jesus Christ

A few blocks away, LeRoy Montgomery — “Sheriff Bubba,” as he’s known around town — sat in his office. On the wall was a movie still from an old Our Gang film. Buckwheat was cross-examining Alfalfa under the stem and unyielding gaze of Judge Spanky. Alfalfa looked surprised. But then, Alfalfa always looked surprised.

The sheriff did not want to talk about what happened to Sam Owens. “I don’t want to talk about it until everything has been settled,” he explained.

He admitted that his officers receive no training in how to handle the mentally ill, and that his department has no written policy regarding mental health care.

“Our response is not significantly different in any situation where an individual is temporarily berserk,” he said. “There’s not a great deal of difference in the way they behave.”

Finally, he cut the conversation off. “There’s been a lot of television and newspaper writing about this, and we just don’t want to go into it,” he said. “They were that away about Jesus Christ. They crucified him. There is no way you can satisfy everybody’s opinion.”

The Same Mistakes

John O’Leary knows that law enforcement officers in South Carolina receive no training in how to handle the mentally ill. O’Leary was director of the state Criminal Justice Academy for six years, and also served as president of the National Association of State Directors of Law Enforcement Training.

“There are going to have to be a lot of changes in the way mental health problems fit into law enforcement,” O’Leary said. “Officers are treating people who are mentally ill as criminals.”

O’Leary is looking at the death of Sam Owens from a slightly different angle. As the attorney for the Owens family, he is preparing to sue Fairfield County, alleging that deputies were improperly trained to handle a mentally ill person like Sam.

“We are not challenging that Lewis shot Sam Owens in self-defense,” O’Leary said. “The question we have is, why did they let it get to the point where they had to shoot him?”

Only two Southern cities — Chapel Hill, North Carolina and Atlanta, Georgia — employ social workers to give officers mental health training and accompany them on calls. Jim Huegerich, a social worker who heads the Chapel Hill crisis unit, said police have come to rely on social workers to defuse emotionally charged situations. “Most officers come up to us afterward and say, ‘I’d rather have one of you than three of us.’”

John O’Leary said other towns need to provide similar training. “I hope law enforcement can learn from situations like this,” he said. “Unfortunately, most times we don’t. We’re still making the same mistakes now that we did 20 years ago. And that’s sad. Situations like Sam are a tragedy for the whole community.”

People in Winnsboro say they won’t give up until officers are taught to treat the mentally ill with respect. They predict that things may change come next election.

“Shit, most people think the damn sheriff should have been fired,” said the barber, Earl Bonne. “They voted him in — I guess they can vote him out.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.