This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 3, "Inside Looking Out." Find more from that issue here.

Roanoke, Va. — Doug Wilder courts potential contributors to his gubernatorial campaign by taking them to lunch at the Commonwealth Club, a genteel preserve of the Virginia aristocracy that only last year admitted its first black member. His political trademark is barnstorming the backroads of rural Virginia, dropping in at country stores to slap backs, shake hands, and pose for pictures in front of Confederate flags. Last winter, he was a star guest at the Democratic Leadership Council bash in Philadelphia for party centrists.

So what makes Doug Wilder different from any other Southern Democrat?

Well, for starters, there’s his complexion.

Doug Wilder is black.

And, although we don’t know whether Pete Rose has put any money down on Wilder yet, he’s an even bet to be elected governor of Virginia this November. The campaign’s first poll put Wilder in a dead heat with his Republican opponent — not bad when you consider that the Old Dominion isn’t exactly a trend-setter when it comes to politics. (The joke here goes: How many Virginians does it take to change a light bulb? Answer: five. One to change the bulb and four to reminisce about how much better the old one was.)

No black has ever been elected governor anywhere in the nation. Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley went to bed a winner on election night in 1982 and woke up a loser, after the absentee ballots came in. In 1986, both he and Wayne County executive Bill Lucas in Michigan came up short against entrenched incumbents.

So what makes anyone think Doug Wilder will fare any better this year in a Southern state — one where there’s a relatively small black vote (18 percent, as compared to 35 percent in Mississippi) and where the state song still glorifies slavery with references to “massa” and “this old darky”?

For one thing, the political landscape couldn’t be more favorable. Governor Jerry Baliles and former Governor Chuck Robb, now a U.S. Senator, are popular, middle-of-the-road New South Democrats, so Wilder has the unlikely advantage of positioning himself as the low-risk candidate of the status quo. To preserve their gains he’s even billed himself as a “conservator,” which some joke is Wilder’s campaign for the hard-of-hearing (“Eh? What’s that you say? Doug Wilder’s a conservative?”). That’s a big reason why strategists on both sides look for a campaign that won’t be decided until the final weekend.

While Jesse Jackson’s presidential campaigns and the racially polarizing mayoral elections in Chicago have dominated the national news, a remarkable story of black political progress has been quietly unfolding in Virginia.

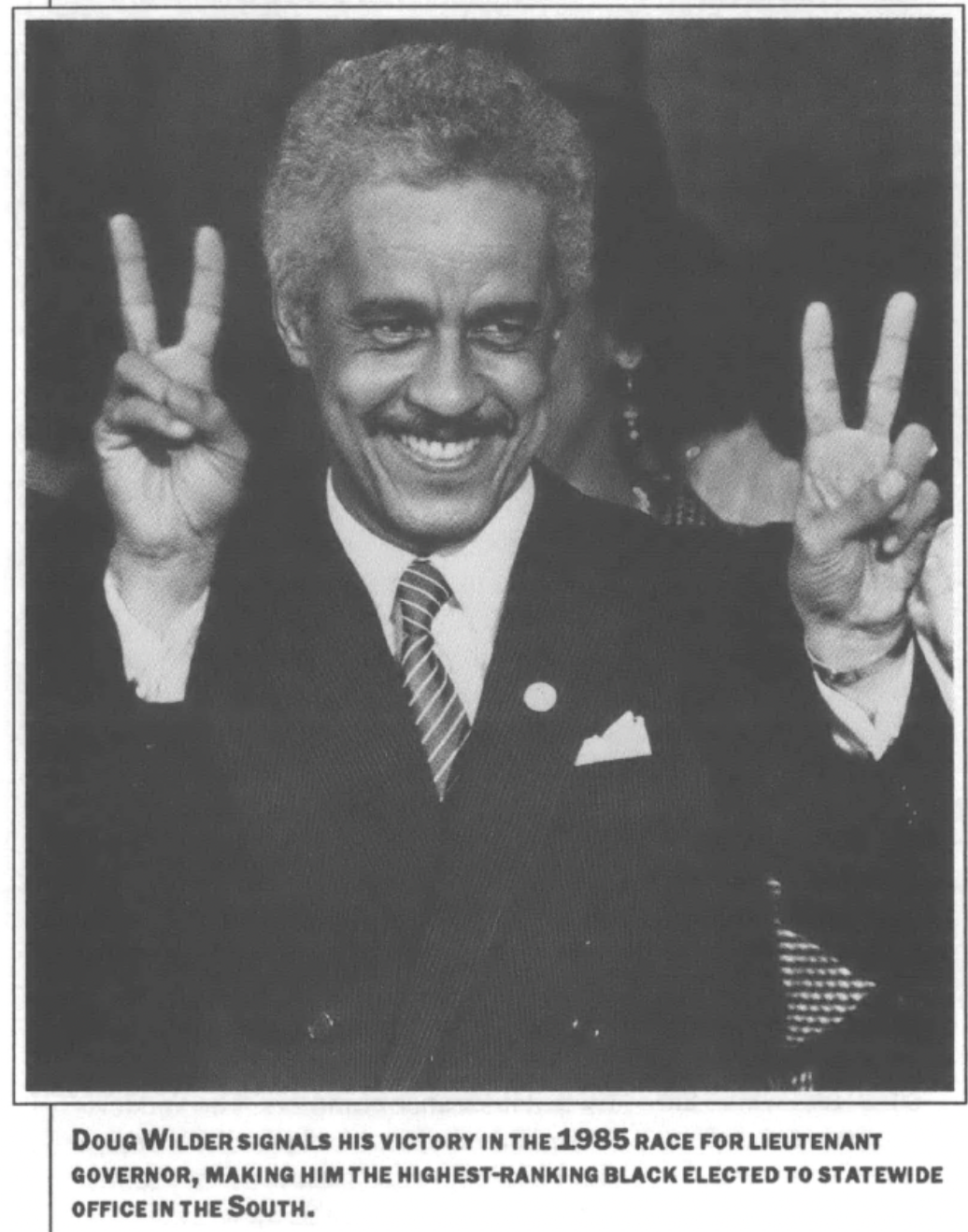

In 1985, Doug Wilder defied the odds and was elected lieutenant governor, one of the few blacks anywhere to win a statewide election. Now political handicappers are so high on Wilder’s chances of winning the governorship that Larry Sabato, an analyst at the University of Virginia and perhaps the state’s most respected political observer, is already touting Wilder as a potential national celebrity, a rival to Jackson, a sure finalist on any Democratic nominee’s list of vice-presidential prospects.

So what gives in Virginia? How has this 58-year-old grandson of slaves managed to come so close to having the most exclusive address in the capital of the old Confederacy?

It’s a story that even Hollywood would be hard-pressed to imagine: a black politician, given up for dead by leaders of his own party, ushered into office on the strength of votes from Appalachian mountaineers and white-flight suburbanites. But it happened. And it’s a story that tells as much about the changing South as it does about Wilder himself.

Carry Me Back

Doug Wilder grew up in the slums of Richmond, the youngest of 10 children. His father supervised agents for a black-owned insurance company. The Wilders were middle-class blacks for their time, the 1930s, but didn’t know it. “My father never made more than $50 a week,” Wilder recalls.

The young Wilder worked his way through high school by shining shoes and washing windows and worked his way through college by waiting tables in the high-class white hotels downtown. He volunteered for combat duty in Korea and won a Bronze Star, yet returned home to find that the only job his chemistry degree qualified him for in the 1950s was as a cook in a juvenile detention center, so he worked his way through law school at Howard University by waiting tables some more.

In 1959, Wilder was the only black to pass the state bar exam. He went home to Richmond to open a law office in the heart of the neighborhood where he had grown up. His practice started out so slim that he often spent his Saturday mornings scrubbing the floor in his overalls while he waited for clients to trickle in. “Nothing’s been given to Doug,” says state legislator Chip Woodrum. “He’s managed it on his own.”

And he’s managed quite well, thank you. Wilder was the first member of his family to own a car. Now he drives a Mercedes. He’s made himself a millionaire speculating in real estate. He belongs to a country club. His law office may still be in the poor, black neighborhood where he grew up, but he now lives in predominantly white and upper-middle-class Ginter Park, in a 15-room Georgian house decorated with art and antiques picked up on his world travels. He employs a housekeeper, favors light opera, dabbles in oils. “He lives the good life,” says Jay Shropshire, state senate clerk and Wilder confidante, “but on the other hand, he’s worked hard to live it.”

Wilder’s aristocratic tastes are reassuring to many white Virginians, accustomed as they are to governors who portray themselves as successors to the old plantation families, not as descendants of the field hands. This is no backwoods preacher out leading marches and whipping up the congregation. Here is a member of the propertied class. Wilder’s resume and lifestyle signal to the captains of industry that he is, in many ways, one of them. This is no black power radical; this is someone they can do business with. An aide to Governor Baliles once offered an unusual description of the state’s most prominent black politician: “He talks like a Southern gentleman. He dresses like a Southern gentleman. He acts like a Southern gentleman.” It’s just that his skin is darker than most.

Wilder made his name in Virginia politics nearly two decades ago when, as a freshman state senator, he outraged colleagues by stalking out of an official reception where the state song was played. “Carry Me Back to Old Virginia” was racist, he said. Wilder’s outburst horrified tradition-minded Virginians who revered the song, and his attempts to repeal the anthem failed. “But they don’t play it anymore,” he says with obvious glee.

From then on, whenever Doug Wilder got his name in the paper, it was usually for tackling racial issues: pushing for a Martin Luther King holiday, accusing the state speaker of the house of suffering from a “magnolia mentality” and threatening to campaign against him, threatening to lead black Democrats out of the party altogether if it didn’t nominate more liberal candidates.

Along the way, though, Wilder also accumulated legislative seniority — and committee chairmanships. A survey of legislators and lobbyists ranked him the fifth most influential senator. The classic outsider became the consummate political insider. One way or another, Shropshire says, “every governor of Virginia has had to go through Doug Wilder.”

When Chuck Robb restored the Democrats to the governor’s mansion after a 12-year absence in 1981, his staff consulted with Wilder on an almost daily basis about appointments. That might have been enough for some politicians, but not Doug Wilder. He’d seen enough Virginia governors up close to conclude that the only difference between them and him was their skin color. What the man who enjoyed speculating on rental property in low-income neighborhoods really wanted was a temporary lease on the fine old beige mansion in Capitol Square.

Long-Lost Cousin

In 1985, Wilder executed his most daring racial power play, bluffing and blustering his way onto the statewide ticket as a candidate for lieutenant governor. Democrats were too afraid to say no; they knew better than to offend their black supporters. So the Democrats gave Wilder the nomination, then gave him up for dead. Republicans joked that their candidate’s chances were the same as his actuarial odds of being alive on Election Day. What neither party counted on was that Wilder wasn’t interested in making a symbolic bid for office; he wanted to win.

To prove he intended to represent all citizens, black and white, Wilder borrowed a station wagon and embarked on an epic journey across Virginia. He pledged to spend two months driving from one end of the state to the other, stopping in every town he came to, no matter how small. And to start his marathon, he ventured into the roughest territory of all, culturally as well as geographically — the rugged coalfields of Appalachia.

Democratic leaders were horrified, and held their breath expecting some racial incident. Instead, folks in the coal counties greeted Wilder like a long-lost cousin.

“Now my daddy hated niggers,” explained Horace Jones, a 66-year-old retired coal miner. “I’ve got more in common with Wilder. He come up hard like I did. I wore patches in my britches and I was ashamed of it, and I’m sure Doug Wilder did too. I think Doug Wilder is for the working man.”

The next thing anyone knew, Wilder was saturating the airwaves with a TV commercial featuring a beefy white police officer giving the black candidate his blessing. Political pros snickered at the corn-pone gimmicks, but they turned Wilder into an unlikely folk hero among white voters who didn’t take the lieutenant governor’s office all that seriously anyway. With a bumbling opponent who ignored Wilder until it was too late, the coattails of a Democratic sweep, and friendly new media that made no effort to contrast his liberal voting record with his newly conservative rhetoric, Wilder won a narrow victory — bolstered by a stunning 44 percent of the white vote.

A fluke? That’s what some analysts said. So with his eye now on an even greater prize, Wilder has spent the last four years trying to reassure skeptical white voters that, deep down, he’s really one of them.

The death penalty? Wilder is not only for it these days, he’s proposing new crimes one can be executed for. Welfare? Wilder has told blacks they need to work harder and not look to government for help. Right-to-work laws? If they’re good for business, Wilder now supports them. In short, whatever positions a middle-of-the-road Democrat would be expected to take in Virginia, Wilder has not merely taken, he’s championed.

The result: Wilder out-maneuvered likely rivals and wrapped up the Democratic nomination more than a year in advance. Some Democrats genuinely saw Wilder as the logical heir to Robb and Baliles; others simply feared alienating black voters by mounting a challenge. Either way, Wilder now faces Republican Marshall Coleman, a telegenic former attorney general.

Race in the Race

How much will race affect the campaign this fall? It’s tough to say. In a close election, you can point to anything and say that made the difference. Maybe some voters won’t like Wilder’s mustache. But, incredible as it may seem, it appears that race won’t be much of a factor.

For one thing, Wilder has a unique appeal to those to whom race usually matters most — rural whites. Through his back-roads tours, Wilder has subtly persuaded many rural whites that they actually have much in common with the state’s most prominent black politician. Coal miner Horace Jones is the prime example.

Besides, there’s not much of rural Virginia left anymore. The Old Dominion is fast becoming a Sunbelt suburbia, as explosive growth in the Washington-Richmond-Norfolk crescent has made Virginia the sixth-fastest growing state in the nation. More than half the state’s voters now live in the suburbs.

There, says analyst Larry Sabato at the University of Virginia, “race cuts both ways. Middle-to upper-middle-class white suburbanites are conservative fiscally but not terribly conservative socially and do not want to be identified with what they regard as low-class, white-trash racism. They want to be associated with Wilder, because he serves as a signal that they are urbane, sophisticated. Wilder has become a badge of honor for middle-and upper-middle-class white suburbanites.”

There’s also the peculiarity of Virginian social upbringing. Virginians may be as racist as the next American, but they’re too polite to say so — and aren’t about to embarrass themselves with a crude display of racism. When Republicans clumsily brought up the subject of Wilder’s skin color in 1985, it backfired like a firecracker at one of those roadside stands Wilder is always dropping by. The GOP lost nine points in the polls overnight. Much like the Old South matrons who discreetly referred to the Civil War as “the late unpleasantness,” Virginians loathe controversy — and some may have felt forced to vote for Wilder last time simply to avoid facing tough questions about why they would reject a man who otherwise seemed perfectly qualified.

So the outcome this time may depend on just how the campaign is framed.

Coleman, taking a cue from George Bush’s 1988 campaign, is trying to accentuate Wilder’s negatives with sharp attacks on his liberal legislative record and questionable real estate deals, suggesting that Wilder simply can’t be trusted to be the reliable middle-of-the-roader he now claims to be. Coleman’s TV campaign — depicting Wilder as a slumlord, a sloppy administrator, a scheming egomaniac willing to take whatever position is convenient at the moment — may be one of the most brutal ever seen in Virginia, a state that prides itself on its gentlemanly style of politics. Can Wilder take the pounding?

Wilder, in turn, aims for a more upbeat, image-oriented campaign. “We want to keep moving forward,” he says. “We don’t want to go back to the 1970s.” That analogy refers to the days when the GOP was last in power, but it conveniently doubles as a metaphor for Virginia’s social progress, too. In effect, Wilder is telling image-conscious suburban voters: Prove you’re not racist by voting for me.

“Can an outstanding black overcome racism and be elected governor?” Sabato asks. “If the election is framed that way, Wilder has it won.”

Abortion and Coal

To avoid startling skittish white voters, Wilder has nailed together a platform of safe issues, including such yawners as “rural economic development,” a buzzword to poor whites and business leaders alike. But he may have found an unexpected crowd-pleaser with one of the most emotional of issues: abortion.

Polls show that, for all their innate conservatism, most Virginians want state abortion laws to stay unchanged. Yet to win the GOP nomination, the relatively moderate Coleman promised the religious right that he would push to outlaw abortion even in cases of rape and incest. So when the Supreme Court tossed the abortion issue back to the states last summer, Wilder was quick to jump on it. His attempt to portray Coleman as a right-wing extremist on abortion has had surprising resonance. When Coleman met with financial backers of the two candidates he defeated for the GOP nomination, abortion dominated the session.

“These are business people who usually don’t care about social issues,” says one astonished Coleman contributor who attended. “They care about the sales tax. But now they’re starting to hear about abortion from their wives and secretaries.”

So score one for Wilder, who now has a chance to peel off some suburban voters who have always supported Republicans on economic issues without paying much attention to the GOP’s social agenda.

Wilder, though, faces a threat from an unlikely quarter — his old coal mining friends in Appalachia. The prolonged United Mine Workers strike against the Pittston Coal Group, which started April 5 and threatens to drag on for years, has turned much of the coalfields into a war zone, with smashed windshields, slashed tires, and burned-out buildings almost a daily occurrence. Governor Baliles sent in state troopers to keep the roads open and Pittston coal trucks moving. That decision outraged union members, who now threaten to take their anger against Baliles out on Wilder either by not voting for him or by writing in the names of union leaders.

The strike has put Wilder in a bind. The southwest Virginia coal fields are a key ingredient in any Democrat’s winning coalition. Yet this is one part of the state where promising to carry on Baliles’s policies actually costs Wilder votes. Yet he can’t disavow Baliles for fear of alienating business leaders and moderate voters elsewhere in the state.

Instead, Wilder has pledged “neutrality,” hoping both sides will think he’s secretly with them. In August, he insisted on retracing his 1985 backroads tour, even though it took him through the heart of the strike zone. Wilder spent a full day stopping by picket shacks, listening to miners give him a piece of their mind. His bravery played well, especially since Coleman has stayed as far away from the strikers as possible. But miners demanded Wilder declare himself firmly on their side. “If this keeps going,” warns striker Ross Miller of Clintwood, “I think the Democrats can kiss the ninth [congressional] district goodbye.”

Pinstripe Coalition

Perhaps the key question, however, is not whether Wilder will win in November, but to what extent his success so far is an isolated phenomenon — or a blueprint that can be duplicated in other states.

Until recently, black politicians have concentrated so much on winning elections in black-majority districts, they haven’t given much thought to exploring the uncharted territory of statewide elections, where they must appeal to white voters as well.

But there are signs that’s beginning to change. In 1990, at least two blacks will be seeking major statewide offices. In Georgia, Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young is eyeing a race for governor. In Illinois, comptroller Roland Burris has already announced for attorney general after initially exploring a gubernatorial bid.

The Wilder example has not been lost on either of them. “Black politicians all over the country, particularly in the South, are looking to Wilder,” says Sabato, the University of Virginia analyst.

“Wilder has a sophisticated and charming air that makes it easy for whites to be attracted to him. In leaping over the racial barrier, you need the right personality — and Wilder is the model of that personality.”

Wilder has always been engaging — warm and witty, dropping quotations from Shakespeare as easily as he assesses the Redskins running game. What’s different lately is that he has moderated his politics. “If you want to be taken seriously in a largely white constituency,” Sabato says, “you have to prove that you will represent that constituency — and almost inevitably that means moving to the middle and abandoning some old-time liberal stands.”

Just as significantly, Wilder also has figured out how to send subliminal signals to middle-class whites that he’s not much different from them. Some are obvious: He no longer mentions racial issues, he schmoozes with business leaders, he surrounds himself with white advisors. If Jesse Jackson has relied on a Rainbow Coalition, Wilder has knitted a pinstripe coalition. Other signals are less intentional, but perhaps more telling: his real estate investments, his home in a well-to-do white neighborhood, his children who graduated from the prestigious University of Virginia.

Wilder’s biggest challenge “is to allay fear, some vague, non-specific fear, [to convince white voters] to be comfortable with him,” says Larry Framme, chairman of Virginia’s Democratic Party. And Wilder’s middle-class trappings do more to help him than any specially made TV spot could do. Class, contends Paul Goldman, Wilder’s top strategist, is ultimately a bigger hurdle than race.

Goldman, in fact, suggests black politicians may find it easier to win white votes in the South than anywhere else.

In 1986, fresh off the Wilder upset, Goldman went to Pennsylvania to advise Dwight Evans, a black state legislator seeking the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor. But the New York lawyer and political consultant encountered difficulties in exporting the Wilder phenomenon.

“Virginia is light years ahead of Pennsylvania on race,” Goldman says. “I can’t believe it. In the South, if you get past race, you have to look hard for the next prejudice. Up there, you have ethnicity, religion, neighborhoods, ward leaders. So much in the South is put on that one arbitrary distinction, when you bust through that, you get voters who are a little more honest.”

Tags

Dwayne Yancey

Dwayne Yancey is a reporter for the Roanoke Times & World-News and the author of When Hell Froze Over (Taylor Publishing, 1988), a book about Doug Wilder now in its third printing. (1989)

Roanoke Times World-News (1987)