This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 2, "Ruling the Roost." Find more from that issue here.

On February 26, 1972, a giant dam of coal waste created by the Pittston Company broke on Buffalo Creek in West Virginia. Pittston officials and engineers knew the dam was unsafe; so did residents, who complained right up until the disaster. The rushing wall of water blasted the hollow’s soil down to the rock, carried away every building in its path, picked up bridges and left twisted railroad track suspended in mid-air. In the space of a few minutes, 125 men, women, and children were killed and 4,000 left homeless.

Pittston’s first response was to label the disaster “an act of God.” According to the company, the slag dam was “incapable of holding the water God poured into it.” My own analysis was quite different. I had grown up in a coal camp in a neighboring county. A slag dam stood at the head of that holler and I could easily imagine it breaking, imagine the communities I had known washed away. Buffalo Creek revealed the coal industry in all its nakedness, an enemy of the people who live in the central Appalachians, the destroyer not just of mountains and streams but of culture, community, family.

In fact, I did lose my community, not to a broken dam but to coal-field economics. I am an exile, as anyone from the mountains must be after being uprooted by coal. Black Wolf, the camp where I grew up, passed through a series of hands before being torn down. My family resettled near Charleston, severing close ties with uncles, aunts, cousins, neighbors. What I found, to my sorrow, is that once those ties have broken, once the community has been left or lost, it can never be restored or duplicated. The extended family is still alive in the mountains, still provides support, both emotional and economic, for those who remain. It does not easily admit strangers, even strangers with roots.

There is, however, a compensation for the hillbilly in exile. Although the particular mountain place has been lost, there is now the freedom to belong to an entire region. It is a belonging which makes one vulnerable, for every assault on the mountains cuts deep, and there are many assaults. The latest, and perhaps the most crucial to date, is being launched by that familiar nemesis, Pittston. The same company that destroyed Buffalo Creek with so little remorse has undertaken a policy which, if successful, will devastate a three-county area in southwest Virginia, deal the final blow to what remains of a community on Buffalo Creek, and perhaps reduce the United Mine Workers of America to a shell of an organization with no more than nominal power.

Blast and Gouge

The Pittston Company is the leading coal producer in southwest Virginia, and a major force in West Virginia and eastern Kentucky as well. In 1987, Pittston pulled out of membership in the Bituminous Coal Operators’ Association (BCOA), and announced it would not accept the contract the BCOA recently negotiated with the United Mine Workers. The UMW has a longstanding tradition — no contract, no work. It was therefore highly unusual when the union announced its members would stay on the job without a contract, as a good-faith gesture designed to avoid a strike. Pittston responded by immediately cutting off the medical benefits of 1,500 retirees, widows, and disabled miners. According to Pittston spokesman William J. Byrne, “[A medical card] is like a credit card that expires. Theirs expired.”

Pittston is not the first company to try a strategy of abandonment. In 1985, A.T. Massey broke with the BCOA and successfully withstood a strike. Massey, like Pittston, began transferring its mineral reserves — and mining jobs — to non-union subsidiaries. Many fear if Pittston also succeeds, other companies will quickly follow suit. And the final result would not only break the union, it would effectively clear the way for absolute power over a vast energy reservation.

In an interview with the Charleston Daily Mail, Douglas Blackburn, a supervisor for an A.T. Massey subsidiary, said, “I think southern West Virginia will be restructured, and I think worldwide economics will force that restructuring. I think it’ll be traumatic. The coal mining population will be very small. There’ll be a nucleus of efficient, effective coal operators. Many of the jobs that have been reduced over the years will never return. The most significant change we’ll face is that our communities will be smaller. Our families and friends will move away.”

The clear implication is that these efficient, effective coal operations will be non-union. It is equally clear that the industry intends the continued massive depopulation of the Appalachian coalfields, the better to blast and gouge the landscape into oblivion. People complain when their drinking water is contaminated, when a slide from a strip job damages their property, when their house falls in above a longwall operation. People demand better wages and benefits and working conditions. People are in the way. The only institution which stands between coalfield communities and their dispersal, the institution those communities fought for and which has served as a buffer between the miner and the willful neglect of coal companies, is the union.

Nazis and Communists

After 14 months of working without a contract, giving Pittston ample time to reverse itself, more than 3,000 union miners struck the company on April 5. Pittston had already hired a notorious “security firm,” the Asset Protection Team, which recruits from the ranks of right-wing mercenaries and is headed by the ex-Secret Service son-in-law of former president Gerald Ford. Replacement miners were quickly hired and housed in barracks at the mine site, and scab truck drivers were recruited from among those who ran coal during the Massey strike.

Pittston also has mounted an advertising campaign in the region’s newspapers, portraying itself as the defender of local communities. “Protecting jobs and coalmining communities are reasons why we are working so hard to achieve a new labor agreement that improves the lives of our employees and, at the same time, reinvigorates the coalfields.” The benevolent company declares that it will make good the contributions to the United Way promised by workers now on strike, in order to provide “badly needed services to members of the community.”

As for the union, it has “failed to adapt to a developing worldwide coal market.” Miners are “henchmen” who in the past have been involved in “killing or wounding” (according to a Wharton Business School study) and who may be so involved again. A gutted company house is pictured, with no explanation that it burned before the strike. Coalfield residents are urged to “let UMW President Richard Trumka know that you join him in asking striking miners to stop the violence. . . . Tell Mr. Trumka this community will no longer tolerate these acts of illegal ‘civil disobedience.’” On a National Public Radio news broadcast, Pittston President Michael Odom says, “This is the same thing the Ku Klux Klan do, the same thing the Nazis do, the same thing the Communists do. They come in and try to overthrow the government.”

Putting Aside Hate

I have twice been to picket sites in Virginia. I have been arrested on the picket line both times, in the civil disobedience which Pittston so blithely links to violence. I have a different story to tell.

I was first arrested with 26 others, mostly miners and their wives, along with a handful of local church people. We gathered at the Moss No. 3 preparation plant near Dante, a site that is key to the strike because of the volume of coal it handles. Almost daily, people are arrested for sitting in front of coal trucks. The trucks are running slowly and are only half full.

There has been one violent incident on the picket line at Moss No. 3. A company security pickup truck ran into a crowd of pickets. One miner was thrown onto the hood of the truck, another suffered three broken vertebrae and was hospitalized in serious condition. Some windshields on company vehicles have been smashed by rocks, but 127 felony counts against pickets for rock throwing have been dismissed for lack of evidence. The number of arrests was itself inflated, since one rock thrown leads to wholesale arrests. And pickets claim the rock throwing, which happens away from the picket line, could just as easily be instigated by company men trying to make the union look bad. Scab truck drivers and company security have already been seen scattering jackrocks, large homemade spikes, in the roads and around pickets’ parked cars. When I have left my car unattended after being arrested, I have always returned to find it guarded by miners worried it would be tampered with.

On my first visit to the picket line I met an old acquaintance, Cosby Totten, one of the first women to work underground. We compared broken windshields to broken backs. “There’s all kinds of violence,” Cosby said. “What mining does to a person’s body is violence. What Pittston did to people on Buffalo Creek is violence and tearing apart the community is violence. We’ve let them say what violence is. That’s our fault.”

Cosby’s willingness to take the blame is typical of the humility of Appalachian mountain people. I was reminded of it when I gathered with others on the eve of my second arrest. This time more church people gathered, including a Catholic nun, six Episcopal priests, a lawyer, a college student. We would be joined by over 100 miners, relatives, and neighbors.

At an evening worship service, people prayed that the hearts of Pittston officials would be changed. During a time of sharing I confessed to a lack of faith and a hatred for coal companies after a neighbor had been killed in the mines, after Buffalo Creek. When the gathering broke up, a new friend, Gaye Martin, approached.

“I understand what you said about hate,” she said. She pulled me into a chair, sat beside me with her arm on my shoulders. “My father was killed in the mines. Two years later my brother was killed in the mines. Ten days after that my husband’s brother was killed in the mines. I’ve had reason to hate. But it destroys you so you have to put it aside.”

There are many Gaye Martins in this strike and they are its heart and soul. Union organizer Marty Hudson speaks of the wife he sees only once a month. One miner tells of his brother, a construction worker who is crossing the picket line so he won’t lose his own job. Another picket has a brother among the state police. The prosecuting attorney for Russell County has a father on the picket line. Fred Wallace, a large man with a gentle face, tapes conversations with people on the picket line because the reasons they give for their presence help sustain him when he gets discouraged. Harry Whitaker is a minister who must sleep propped up on pillows because he is in the last stages of black lung. He recently went on a four-day bus trip to Pittston’s headquarters in Greenwich, Connecticut, where company officials made light of his medical problems.

We gathered along the road outside the main gate of Moss No. 3. There was little traffic until a convoy of coal trucks arrived, kicking up swirls of coal dust as they made the turn into the plant. On a hill inside the gates a guard tower stands, and below it men in black uniforms aimed video cameras at us. Some in the crowd jeered the passing trucks; there were also some catcalls when a wedge of 20 state police moved in. Two local musicians played “Union Maid” and mountain banjo tunes beside a sign that proclaimed THIS IS SOUTHWEST VIRGINIA NOT SOUTH AFRICA. Then a group of miners sat in front of an oncoming truck. The truck stopped, brakes squealing, and the police moved in.

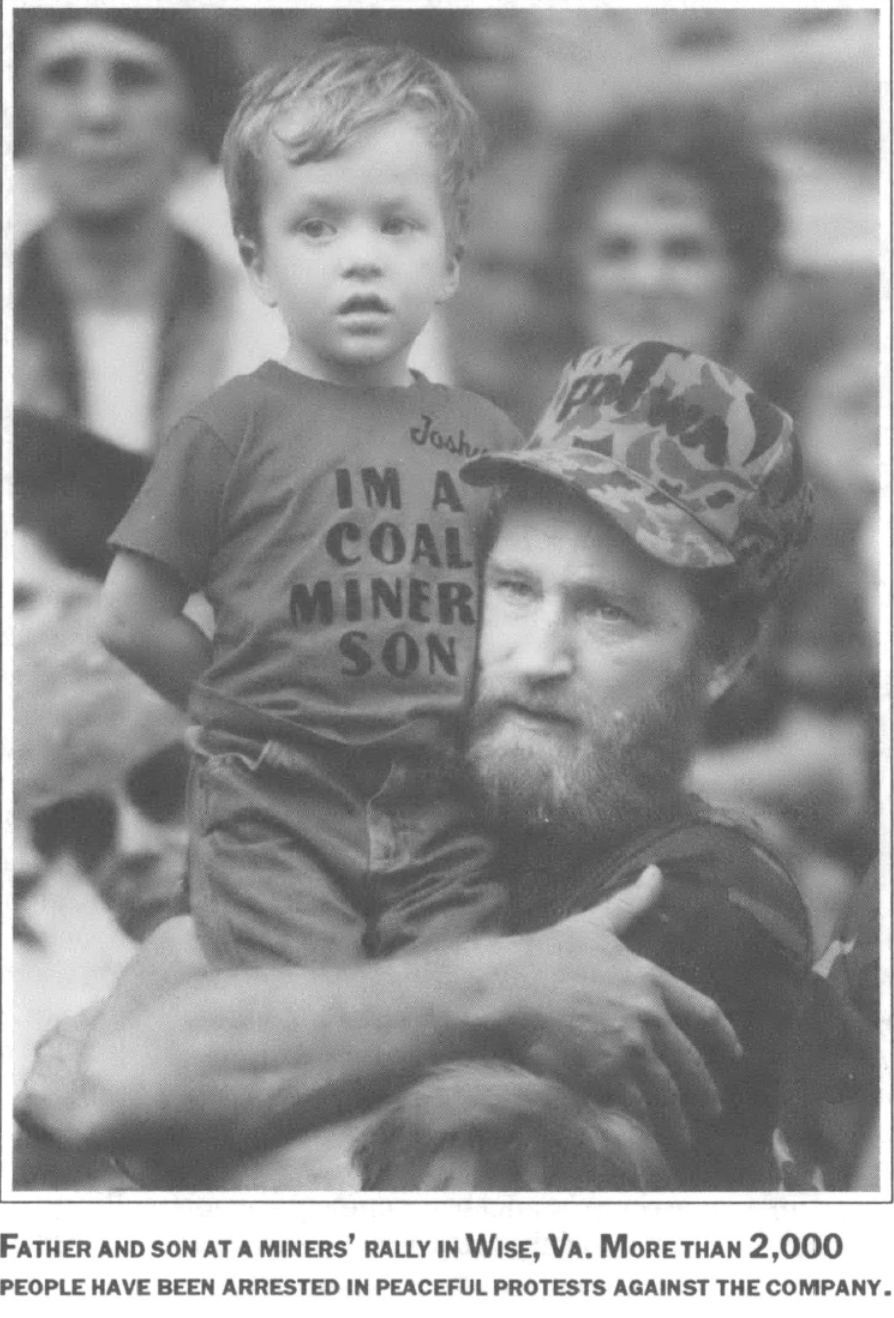

Gail Gentry was paralyzed after his back was crushed in the mine and now has no medical coverage. He rolled his wheelchair in front of a truck and became the 2,000th person arrested on the picket line. As state police surrounded him, a prayer was offered up. Two policemen stopped and removed their hats. After Gale was taken away, the rest of us moved in.

As I knelt, an elderly man came from the crowd and took my arm. “We love you,” he said. He was crying. “We love you, we love you.” Later, as some of us waited on a prison bus to be taken away, he poked a package of Nabs through the bus window. Then he backed away and held up two fingers in the form of a cross. We shared the Nabs among 15 people.

There is a strong religious strain in the Pittston strike. I bring it up not to convince unbelievers but to show how the values of the community as a whole are bound up in this crisis. The union miners on strike against Pittston are not some lawless minority. Most of them are breaking the law for the first time in their lives when they sit down on the picket line; it is an action they do not take lightly. They are supported by many neighbors and local business people. In a nation that puts a premium on upward mobility, they have given up middle-class salaries to live on $800 a month in strike benefits. They have put up their homes to bond people out of jail after arrest on the picket line.

The entire community has been disrupted by the strike. The deputy sheriff who drove me to the Russell County jail had worked from five p.m. to five a.m. the previous night and was in the middle of another long shift. Motel rooms have all been taken by state police so that visitors to the area have no place to stay; the police themselves rarely see their families. Grocery stores dip into their stock to donate food to those in jail. Pittston’s white-collar workers, most of them caught in the middle, are estranged from coal-mining relatives; their children feel isolated at school. The architects of all this misery dwell secure in Greenwich, Connecticut, where the average selling price of a home last year was $791,543 and no one has seen the coal fields. What gives them the right to disrupt the lives of so many people? What gives them the power of life and death over an entire community? Those are the questions I heard over and over again on the picket line.

A busload of miners have returned from a shareholders’ meeting in Greenwich and play a tape of the proceedings. On the tape, some miners object to a company proposal to force work on Sunday, a practice which would keep them from attending church. A Pittston official suggests that the religious issue is being used as a “crutch.” A miner responds: “I use church to get through work during the week.” [laughter from Pittston people]

The miner, serious: “That’s my crutch in life, the whole meaning of it, because I hope to go to a better place when this is over.”

Pittston executive: “Come to Greenwich.” [more laughter]

For too long the myth of American mobility has been used to justify corporate policies that show no regard for stable communities. Appalachian rootedness stands square in the way of these policies. Mountain people leave their region with the greatest reluctance and return whenever they can. Pittston President Michael Odom, speaking with a Roanoke newspaper reporter, said of union miners facing layoffs, “They just won’t leave, for some reason.”

And that is what the Pittston strike is all about.

Tags

Denise Giardina

Denise Giardina, the author of Storming Heaven, lives in Whitesburg, Kentucky. (1991)