This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 2, "Ruling the Roost." Find more from that issue here.

Last night I fell asleep in Detroit City

And dreamed about those cottonfields back home.

I dreamed about my mother

Dear old father, sister, and brother,

And I dreamed about the girl I left so far behind.

I want to go home.

I want to go home.

Oh, how I want to go home.

— Mel Tillis, “Detroit City”

I pulled into Detroit for the first time in my life after a long, hard drive from West Virginia on the Fourth of July. That was eight years ago, but I still remember the man I met at the gas station when I stopped to fill my tank.

It was a Sunoco station on East Jefferson Avenue, about halfway between the burned-out shell of the Uniroyal tire factory and the up-scale neighborhoods of Grosse Pointe. The owner came out, wiping his hands on his greasy blue coveralls, cast a disgusted look at my German-made Volkswagen, and proceeded to fill ’er up.

Then he saw my license plate. “You from West Virginia?” he asked in a familiar mountain accent. I said yes, and he suddenly looked like he wasn’t sure whether he wanted to laugh or cry.

“Me too!” he said, grinning and shaking my hand through the open car window. “Name’s Jesse. Wherebouts you from?”

“Shepherdstown,” I said. “How ’bout you?”

“Bluefield,” he said proudly. “Know where that is?”

“Sure. Home of the Bluebirds.”

“That’s right!” he said, amazed that anyone would recognize the minor league ball club from his home town. My familiarity instantly qualified me as a long-lost cousin. We talked baseball and badmouthed a few West Virginia politicians until he noticed my tank was full.

“How much I owe you?” I asked. “Forget it,” he grinned. “It’s on me.” When I protested, he shook my hand again. “What’s the use of owning a gas station if you can’t pump gas for one of your own?” he asked.

I didn’t know it that day, but my drive from West Virginia to Detroit had followed a trail cut by millions of men and women like Jesse who have left the South in search of work, food, a better life for their families. I soon discovered entire Southern communities in and around Detroit, from the black neighborhoods of the Near East Side to the hillbilly outposts of Cass Corridor and Ypsilanti (known derisively as “Ypsi-tucky” because of its heavy concentration of Appalachian immigrants).

And not just Detroit, but Chicago, Toledo, Dayton, Akron, Pittsburgh, New York — Southerners have settled in every urban industrial center in the North, transplanting their values and cultures and communities in a land that often appears strange and hostile. Demographers, journalists, and academics call it “migration,” making the mass movement of people seem as natural and inevitable as a flock of geese taking wing. In fact, the term obscures the economic and physical violence that has uprooted homes, families, and entire communities from the coal fields of Bluefield to the cotton fields of the Delta. Jesse and many of the others who have moved North since the turn of the century are not migrants — they are refugees, working people driven from their land to fill factory jobs in Northern industries.

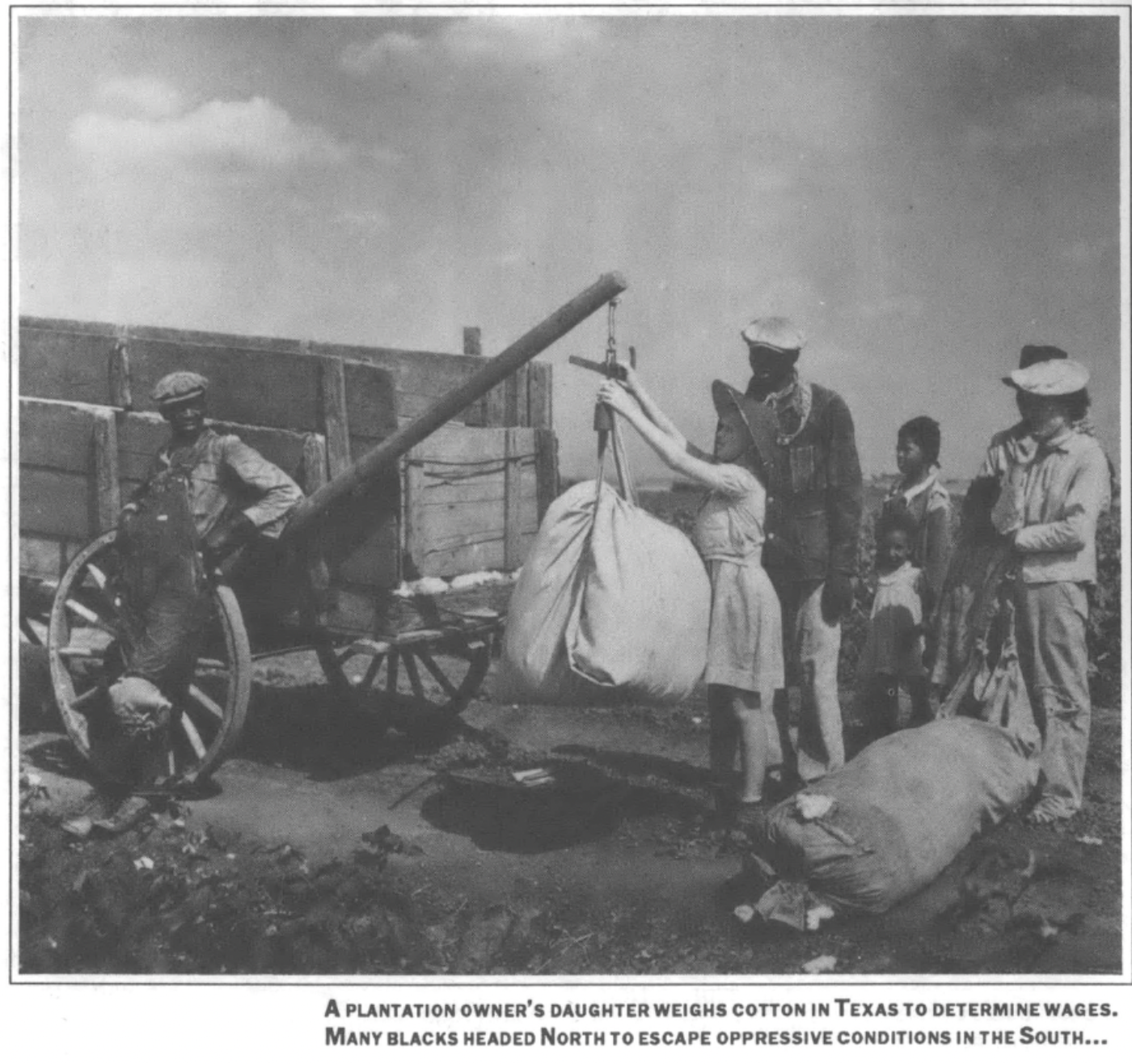

The first mass exodus from the South dates back to World War I. Between 1915 and 1940, hundreds of thousands of Southerners — almost all rural blacks — left their homes in search of better lives in the urban North. The movement became known as the Great Migration.

“The decision to leave the South was prompted by many circumstances,” says Spencer Crew, a historian at the Smithsonian Institution and curator of “Field to Factory,” an exhibit on the migration. “Among the reasons were the systematic practice of discriminating against Afro-Americans, known as Jim Crow laws, and natural calamities caused by the boll weevil.”

Many of those who moved were sharecroppers, locked into an ever-tightening circle of debt to their white landlords. With the start of the war, Northern industries found themselves with a shrinking workforce and increased demand to supply the troops fighting in Europe. Many companies hired labor recruiters to locate Southern blacks and lure them north with promises of high wages. Recruiters also promised blacks a better education for their children and greater personal freedom for themselves.

Freeman Patton was one Southerner who followed a recruiter north. Born in Paris, Texas, Patton moved to Gary, Indiana with his family in 1911.

“My daddy was working at a high school and my parents felt that the educational advantages would be better in Gary, as well as the social privileges,” Patton told Peter Gottlieb, labor archivist at Pennsylvania State University. “Along that time it seemed to be a migration period, so they decided they would migrate to there. A fellow came down sending people there to work in the steelmill and offering them pretty good advantages, home sites and that sort of thing, and so they migrated there.”

The push to the North slowed during the Depression, but it picked up with the start of World War II. Once again, industry found itself short of workers, and once again companies looked South for labor. This time, though, Southern blacks were joined by hundreds of thousands of Appalachian whites looking for work. Blacks and whites who found higher-paying jobs in the North told their friends back home, and the refugees kept coming.

Freeman Patton worked with white Southerners when he moved from Gary to Pittsburgh to take a job in a steel mill. “They migrated themselves,” he recalled. “A fellow that came from West Virginia, North Carolina, he would come here to Pennsylvania and get a pretty good job. Then he would have to go back home. He would have a friend or a relative, and he’d let them know about the prosperity he was enjoying. It was pretty much the same for black people.”

As blacks and whites who found higher-paying jobs in the North told their friends back home, the flow of Southern refugees continued. Two decades after the war ended, Southerners were still making their way to big Northern cities in search of work. Between 1940 and 1970, more than four million blacks moved from the rural South to the urban North.

What white and black Southerners discovered in the North bore little resemblance to the promised land they expected to find. There were better schools and greater personal freedom, but there were also segregated factories, higher living expenses, and brutal slums.

Blacks in particular often encountered the same racism they had fled. Confined to unskilled jobs and inner-city slums, black Southerners learned that white men were still the boss up North, and the good ol’ boy network still prevailed.

“Whites were top foremen, from West Virginia, Alabama, Georgia, anywhere,” said Freeman Patton. “Some of them had fathers or brothers working in other parts of the mill. They would bring a fellow to me who didn’t know the first thing about gas inspecting, and I would teach him how to be my boss. Then after I trained him he moves up higher, and someone replaces him, and I teach him. They’re paying him more money to let me teach him.”

Refugees like Patton, however, were not passive victims. They had made a decisive move to change their own lives, and their quiet determination also transformed the cities in which they settled.

“These are not people who are usually highlighted in history books or exhibitions,” according to Spencer Crew, the Smithsonian historian. “They did not hold powerful elected offices, lead troops into battle, or write memoirs. They were quiet heroes who sought primarily to create a decent life for themselves and their families as best they could. Migrating offered one way to make a significant change in their lives.”

The very act of moving changed the face of the entire country as well. In 1910, 90 percent of all black Americans lived in the South. By 1970, the percentage had dropped to only half. The swelling black population in the North fueled white flight, creating vast suburbs and altering political districts, zoning decisions, and the location of highways, subways, and bus routes. It also revolutionized urban politics as blacks elected mayors in Gary, Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Washington, D.C.

The refugees brought their diverse cultures with them as well, breathing new life into music, literature, dance, and theater. Appalachian whites recorded their homesickness and disillusionment in countless bluegrass and country hits, while Southern blacks transformed the rhythms of jazz, blues, gospel, soul, and rock ‘n’ roll.

As Southerners like Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers Union, took the lead in the civil rights and labor movements, the lines between North and South continued to blur. Much of what passes for Northern culture and politics often has deep Southern roots — roots that can be traced in the journeys of refugees and their families.

These days, developers and industries in the South like to boast that the tide of migration has changed. Today, they say, workers are flocking to the Sunbelt to bask in the glow of economic prosperity.

Statistics certainly show that the South has been gaining residents for the first time this century. Since 1965, according to the Census Bureau, the region has netted more than six million people in the ebb and flow of shifting populations. A century ago, only two percent of those born in the North resided in the South. Today, 12 percent of all Northerners live below the Mason-Dixon line.

But the numbers don’t tell the whole story. Researchers who have taken a closer look at the figures say that many of those moving to the South are the Southern refugees and their descendants returning to the communities they were forced to leave behind. Some have held on to the land they own in the South for years, waiting for an opportunity to return. Blacks in Chicago, for example, reportedly own more land in Mississippi than blacks in Mississippi.

Sandra Headen, a university professor, spent six years in Chicago and eight years in Boston, but returned to her native North Carolina recently when her daughter Irene was born.

“We wanted our daughter to grow up in the South and be near her grandparents in Greensboro,” Headen told the Raleigh News and Observer. “We wanted her to understand what her heritage is. Roots had always been important to us.”

Like Irene, many of those moving back to the region are children. According to a recent United Nations survey, a third of all interregional moves in the U.S. were made by children under the age of 15. But unlike Irene, some children make the journey alone, without parents or friends.

Carol Stack, a Duke University anthropologist currently at the University of California, is writing a book on blacks returning to the region entitled The Proving Ground. According to Stack, some of what appears to be one-way “migration” is actually children moving back and forth between parents in the urban North and grandparents and other relatives in the rural South.

“When I was a child, I traveled back and forth between my mother’s place in Brooklyn and this old house, my grandparents’ homeplace,” said Charlotte Copeland, a black woman who spoke with Stack after returning to rural North Carolina. “I would spend school years or summers in either place, but most of my high school years were spent in North Carolina. Going back and forth I gained a skill that has served me well. I can maintain in the city and I can maintain in the country. I can adjust because a part of me knows both places.”

According to Stack and John Cromartie, a geographer at the University of North Carolina population center, nearly 350,000 blacks moved to the South between 1975 and 1980. A third of those who moved were children, and more than 70 percent were either born in the South or were “homeplace movers” joining relatives in the region.

Most of the children returned to counties in rural areas in North and South Carolina, Alabama, and Mississippi. “Homeplace children are moving to the very communities, urban and rural, which originally accounted for the majority of northbound migrants,” say Stack and Cromartie.

Sandra, a young girl Stack interviewed, decided to stay with her grandparents in the South despite her mother’s wishes to have her join the family in New York. “I was torn between both, but my grandmother is old and has no one to take care of her,” Sandra said. “My parents have each other.”

Sometimes children said they preferred to live in the South, much as their ancestors who journeyed North dreamed of returning home someday. “I should stay with my grandparents,” Helen told her parents, “because for one, there are many murderers up North, and my grandparents are old and need my help around the house.”

Refugees are coming home, looking for work or searching for their roots or bringing their children to live with relatives. But for hundreds of thousands of uprooted Southerners the reunion is incomplete, and families remain fragmented, displaced.

One Southern girl — one of 100 children interviewed by Stack on their experiences in the North and South — wrote a letter to “Dear Abby” about a dilemma she faces. Her words sum up the painful uncertainty confronting Southern refugees and their descendants, tom between two families, two regions.

“Dear Abby,” she wrote. “I am 12 and my brother is 10. My mother wants us to go and stay with her in New York City, and my grandparents want us to stay back home with them. “What should we do?”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.