This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 2, "Ruling the Roost." Find more from that issue here.

Charlotte, N.C. — In 1973, when Charley Kuhn hired in at a West Virginia coal mine, he thought he was set for life. “There’s 80 years of coal here,” the company told him. “You can retire here, your son can retire here, and your son’s son can retire here.”

The job lasted 13 years. Then U.S. Steel closed its Winifrede mine near Cabin Creek and, a few months later, sealed it shut. Kuhn looked for a job around Charleston, but no one had work for an ex-longwall helper with mechanical skills.

Kuhn regularly drove from his home in Bim to a newsstand 30 miles away to buy armfuls of out-of-state newspapers. In 1987 he mailed his resume to a company that advertised in the thick classified section of The Charlotte Observer in North Carolina.

Federal training money paid for Kuhn’s first visit to Charlotte. A loan from his father paid for his move. Now he wears his metal-topped miner’s safety shoes as he repairs trash compactors for a firm just outside Charlotte. His starting wage was $7.50 an hour, half of what he made underground.

Kuhn never expected to leave West Virginia. He didn’t expect to become penniless, either. “I knew it was a big decision,” says Kuhn, an easygoing, bespectacled man of 37, “but I just got tired of sitting around the house, never knowing when the coal mines were going to open up.”

Kuhn, pausing after a welding job at Container Corporation of Carolina, says he’s settling in. His wife has a second job in a doctor’s office and his son, in the eighth grade, is wondering about marine biology as a career. “We’ll probably stay down here, I figure,” he says in his Boone County drawl.

Paying the Price

Kuhn is not alone. Miners, laborers, hospital workers, engineers — they’re finding work in western North Carolina, where Interstate 77 straightens from its snakelike Appalachian path and fog-shrouded mountains give way to plains bustling with commerce.

West Virginians, dependent on a fickle coal economy, have always left home. A quarter-century ago, they moved in convoys to cities like Detroit and Akron, Midwestern meccas fueled by the auto industry. In the schoolroom, as the saying went, students learned “Readin’, writin’ and Route 21.” Between 1950 and 1970, state figures show, 750,000 people left the state.

These days, West Virginians looking for work are heading south instead of north, to places like Virginia, Florida, North Carolina, and Washington, D.C. Although the current outmigration can’t be compared to that of the ’50s and ’60s, thousands of residents continue to leave the state each year. According to state statistics, 86,000 people departed between 1980 and 1986 — roughly 44 of every 1,000 residents. Over a 20-year period, the current rate would project to about 290,000.

One of the most-traveled roads out these days seems to be I-77, the familiar first leg of vacation trips to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. West Virginians around Charlotte say they bump into fellow Mountaineers every day.

“I went to the motorcycle shop and there were two people wearing West Virginia jackets in the showroom and it looked normal,” recalls Don Bailey, county engineer for adjacent Gaston County. “I think half of Charlotte is from West Virginia.”

The day Rod Snyder, a recent West Virginia University graduate, moved to Charlotte, he felt a strong case of deja vu. Or maybe deja WVU. He stepped outside his apartment and saw a classmate. He walked to a convenience store and spotted another. “I was here for 15 minutes and saw two people from Morgantown,” Snyder remembers with a chuckle. “I was thinking, ‘Yeah, I like this place.’”

To some, this is a land of opportunity with plentiful jobs, good weather, and lots to do. West Virginians hardened to gloomy economic news enter a new world. “When I moved here, it was culture shock — every day on the news, you hear about new businesses coming in,” says Donna Cox, a 1983 Marshall University graduate who works as a newspaper reporter in Newton, North Carolina.

Often, however, there’s a price to pay. In right-to-work North Carolina, many, like Kuhn, earn far less than they did in mining and manufacturing. Husband-and-wife wages may barely match what the husband once earned on a union job. And many transplanted West Virginians miss their families, friends, and the almost indescribable feeling of home.

“It’s Like Forever”

Economists would say Bill Lee made a rational choice when he left home to find work. But dry economic theory leaves little room for emotion, and it cannot measure the bitterness in Lee’s voice.

“A guy over on the corner just moved back to West Virginia,” says Lee, who works as a carpenter in Claremont, North Carolina near Newton in furniture country. “It makes me sick to watch someone go home.”

When he was 18, Lee left Elkview, West Virginia for a two-year hitch in the Army. “I remember thinking when I got out of the Army, I wasn’t never going to leave home again,” he says.

Back home in the Kanawha Valley, Lee struggled for 10 years, studying at two different trade schools, finding nothing in those fields, working sporadically at laboring jobs. He spent a year and a half at his last construction job, until the company went out of business in the spring of 1986.

Lee spent a month looking for work around Charleston, “which was a joke,” then moved to Raleigh, in central North Carolina, to work construction. He commuted home on weekends, joining the parade of cars with West Virginia license plates that rush north on I-77 every Friday at sundown.

Finally, the six-hour commute got to be too much, and Raleigh was too big a city for a country boy. So Lee moved again in early 1987, joining his brother Don in Claremont, North Carolina. He found a job in six hours, but has yet to find peace. “There’s nothing wrong with North Carolina except that it ain’t West Virginia,” he says.

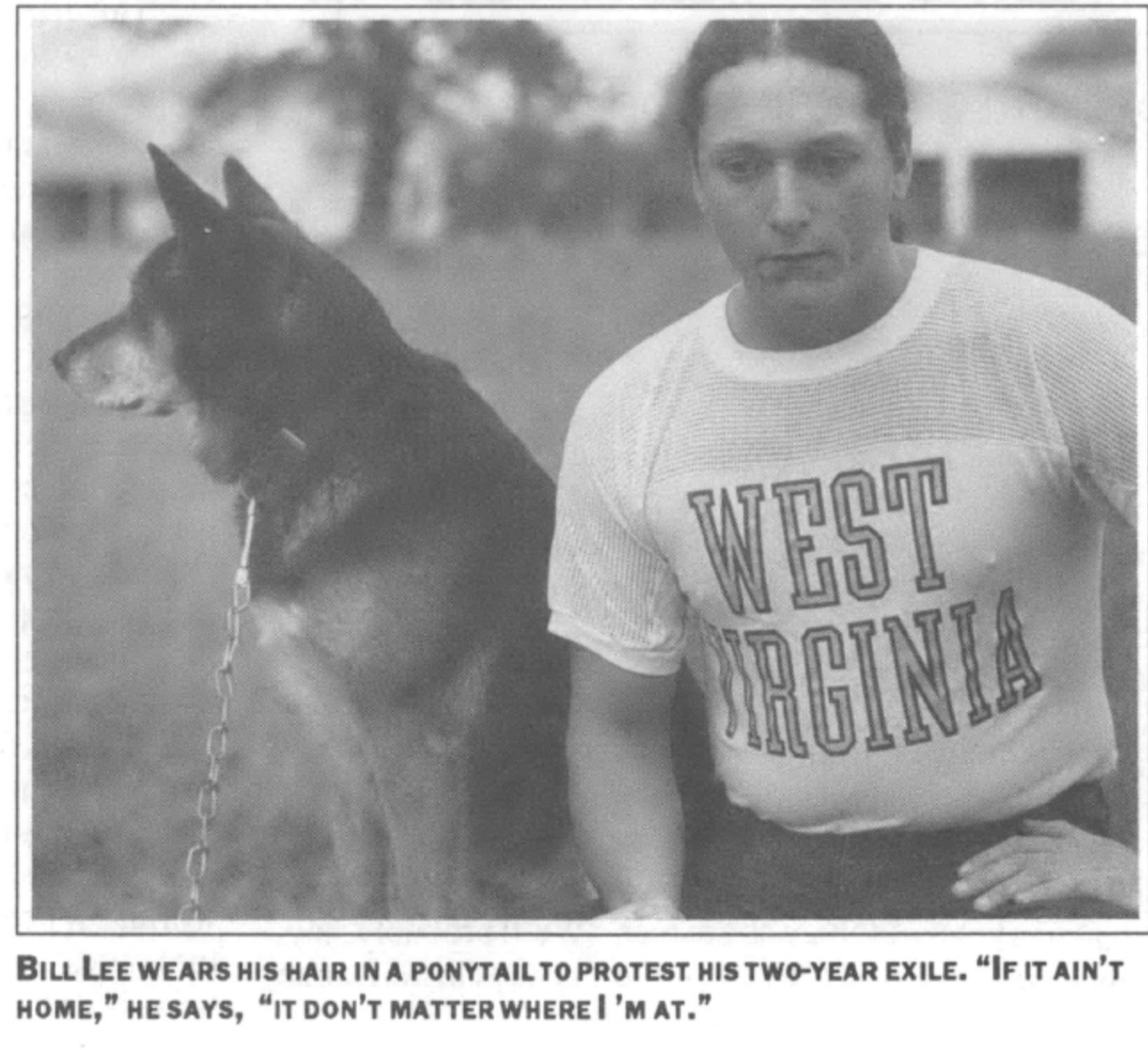

Lee, a tall, rawboned man, wears his light brown hair in a neat ponytail, the first time he’s let it grow in 10 years. He’s thinking about not cutting it until he leaves, a personal protest against his two-year-long exile.

Lee understands something basic about being out of work. “It don’t do a hell of a lot for your self-esteem,” he says softly. “Work gives me a feeling that nothin’ else can. I don’t do drugs and I don’t drink. The only thing I do that feels good is work.”

But he doesn’t understand why he has no choice about where he works. “I don’t know why it’s like that. There’s a 250-mile difference, but it’s a whole ’nother world.” When Lee visited home for Christmas, he thought about writing a letter to the editor about it, but he couldn’t find the words.

The uncertainty about returning upsets him most. “I can’t see no end,” he says. “When I was sent to Germany in the Army, there was a date and a time. Now, it’s like forever.”

Now Hiring

If the economy around Charlotte is booming, much of its success is being built on the desperation of displaced workers like Lee. The numbers are simple. Around Charlotte, unemployment is three percent. In several West Virginia counties, the rate is in double digits. Many employers in the area are now advertising for workers in West Virginia, offering lower-wage jobs to the unemployed who are willing to leave their homes behind.

Sam Matheney moved to Charlotte after his West Virginia employer went out of business in 1986. He now works as a security guard supervisor at Stegall Security and Protective Services. He oversees 175 people, but earns only three-quarters of what he made in West Virginia cleaning chemical tankers.

At Stegall, the “Now Hiring” sign hangs near the office’s rear entrance. “I guess you could basically call this unskilled labor,” says company vice president Harry Stegall. The company competes against fast-food restaurants for workers.

When Matheney told his boss about West Virginia’s high unemployment rate, Stegall listened. He placed a help-wanted advertisement in the Charleston Sunday newspaper picturing Matheney and three other men in security guard uniforms. “Unemployed? This Could Be You” read the bold-face type over the picture. “All of these men are from areas of high unemployment and moved to Charlotte. They now have a future.”

A week later, Matheney returned to West Virginia to conduct about 40 interviews at the unemployment office in Charleston. He hired eight people who will earn between $4 and $6 an hour. “To be honest with you,” Matheney says, “most of them didn’t want to leave West Virginia.”

Tom and Marie Wendell were two who left. With jobs scarce in Montgomery, West Virginia, they had both been taking vocational courses. They couldn’t afford car fare to finish.

Why did they leave the state? “We was on welfare,” Tom, 23, responds in a low voice, sitting in the Stegall office, filling out paperwork. “You can’t buy a job in Montgomery.”

Now he and Marie, 20, both work at Stegall, with staggered hours so someone will be home to care for their daughter, Savannah. Marie’s brother came, too. “We got down here Monday morning,” Tom said three days after they arrived. “So far, it’s all right.”

The Beaten Path

Many families like the Wendells, caught between mining and minimum wage, discover that both husband and wife have to work to make ends meet in North Carolina. “In order to take advantage of living in a place like this, for almost everybody it requires a two-income household,” says Bill McCoy, director of the Urban Institute at the University of North Carolina in Charlotte.

North Carolina is rated seventh in a national business climate survey, but it ranks 43rd in climate for workers, according to a survey conducted by the non-profit Southern Labor Institute. The Charlotte Chamber of Commerce likes to boast about the low wages and lack of unions in the area, proclaiming that the average manufacturing wage in the city is $7.63, compared with the U.S. average of $9.71.

“The tragedy is when you go to other states, you can work, but you fall into a whole category of the working poor,” says Mike Burdiss, director of lobbying for the United Mine Workers. “You make enough to survive, but you’re not really covered by hospitalization and other benefits that you had under a union environment.”

Despite the lower wages and homesickness, high unemployment in West Virginia continues to drive an increasing number of people from their homes. A yearly survey conducted at West Virginia University shows that 72 percent of 1988 graduates left the state, compared with 62 percent three years ago. This year, the percentage of those leaving is expected to hit 75 percent.

“I’ve been saying since I’ve been doing these surveys that we’re losing our best and brightest in record numbers,” says Robert Kent, director of WVU Career Services. “As long as economic development remains low, the number of students leaving keeps increasing, edging upwards.”

Joe Chandler is head of the WVU alumni chapter in western North Carolina. He is also mayor of Claremont, an industrial town of 1,400 near Statesville. Three years ago, Chandler said, the first annual dinner for ex-West Virginians in the Statesville area drew about 60 people. A year later the dinner drew nearly 200. “We noticed there was an increase of young people coming down,” Chandler said.

At the intersection of I-40 and I-77, Statesville is booming — and Charles Welling has reaped the benefits. A few exits south of I-40, Welling runs the Lake Norman Fuel Stop, a truck repair and filling station.

“We’re right on the beaten path,” says Welling, who operated a wrecker service and garage in Ripley, West Virginia until he moved three years ago. “The economy and taxes were why I left.” Welling sees so many West Virginians at his station that “they have to be all looking” to move.

No North Carolina company is yet recruiting workers from West Virginia in quantity, but everyone has a story about the factory or office that’s filling up with West Virginians.

Rich Shrum, service manager at busy Regal Chrysler-Plymouth in Charlotte, says West Virginia is the only place he’s advertised for mechanics. Why? He responds with a knowing laugh: “Because I’ve heard about the economy of West Virginia.”

In Greenville, Superintendent of Schools Roy Truby also looks to West Virginia for new teachers. “West Virginia is a very fertile area for us to recruit,” he says. Truby should know. He was state superintendent of schools in West Virginia from 1979 to 1985 before he moved to North Carolina.

“I quite often run into people who say, ‘I was in West Virginia when you were state superintendent,’” Truby says.

Mayor Chandler tells a similar story. “I was at an economic development meeting recently,” he says. “Somebody was crying about not getting enough employees. Somebody stood up and said, ‘You’re missing the boat if you don’t get to West Virginia and recruit those people because they are the best workers we have found yet.’”

Surveying the Damage

The flow of workers from West Virginia to other Sunbelt states does more than add to the personal pain of those who are forced to move. It also hurts the West Virginia economy, gutting its labor force of trained workers and making it even harder for the state to recover.

“I’d like to assess the state of North Carolina for every worker we send,” said Ernie Husson, principal of Carver Career Center, a vocational school in Kanawha County, West Virginia. “You can put down all the training you want, but if there’s no place for people to work, if they want to eat, they leave.”

A few years back, Ron Lowe moved his family from Charleston to Florida, working as a surveyor in Orlando and Fort Lauderdale. The Lowes didn’t stay long. “We got homesick and came back to West Virginia,” says Ron, 49.

Now Lowe, who once surveyed power plants and hotels in Charleston, is helping turn timber and farmland just northeast of Charlotte into apartment complexes.

Lowe and his sons Gary and Mark use their surveying tools to map boundaries and plot elevations so roads can be designed. Of 25 people recently working at their land survey firm, Ron says, seven were from West Virginia.

Ron wears a belt buckle with the West Virginia seal. “If there was a lot of opportunity in Charleston, I’d go back,” he says. “We’re still West Virginians.”

His son Gary, 25, also wants to return. His wife prefers Charlotte, but they don’t argue. Gary boils it down simply: “This is where the work’s at, so I’ll have to go where the work’s at.”

Tags

Norman Oder

Norman Oder wrote this story as a reporter at The Gazette in Charleston, West Virginia. He will enter Yale Law School this fall on a one-year fellowship for journalists. (1989)

Charleston Gazette (1988)