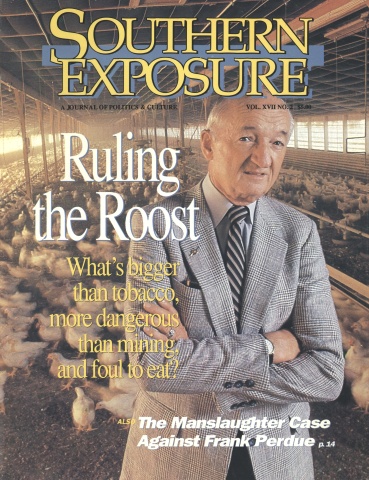

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 2, "Ruling the Roost." Find more from that issue here.

At midaftemoon, more than 100 workers wearing white boots, smocks, and hair nets enter the windowless brick building at the comer of Williams and Roger streets in Buena Vista, Georgia. Others relax on picnic tables or pass the guard house in groups, joking and jostling. Most are young women. Almost all are black.

This is the shift change at a poultry slaughterhouse. For eight hours or more, the women will work at a furious pace to transform tens of thousands of chickens into chilled, packaged meat. Although the plant wall proclaims, “Cargill: Committed to Quality and Safety,” the jobs are hard and tiring, and rank among the riskiest in all industries. The only hints of this at Cargill are the terrycloth wrist supports many workers wear, the “No Trespassing” signs, and the fence topped with barbed wire that rings the processing plant.

In many rural towns like Buena Vista, where factory jobs are scarce, people consider themselves lucky to get work in a chicken plant. Unlike a tobacco field, the plant has a roof, and the work is steadier than seasonal farm labor. Hourly earnings for the 550 Cargill employees range from $5.10 to $5.60 — the highest wages in the area and far better than the minimum wage paid by fast-food joints or convenience stores.

But the money earned in poultry plants — about $40 a day — comes at a high price. According to poultry workers interviewed in six Southern states, conditions inside the processing plants are grueling. Workers stand in temperatures that range from freezing to 95 degrees, sometimes crowded so close together that the bloody water dripping from co-workers’ moving hands splashes in their eyes. Supervisors, few in number and primarily white men, reportedly trade promotions for sexual favors. They yell at workers, treat them “like children or step-children,” intimidate them. Many call their jobs “slavery.”

Work rules in some plants are so rigid that employees forbidden to take a break have urinated, vomited, and even miscarried while standing on the assembly line. They get eye infections, skin rashes, warts, and cuts. Worse yet, the speed and repetition of the jobs can injure their shoulders and cripple their hands, leaving them permanently disabled.

“Work in poultry plants by every stretch of the imagination is horrible,” says Artemis, a white poultry worker from northern Arkansas. “It’s stressful, demanding, noisy, dirty. You’re around slimy dead bodies all the time. And it’s very dangerous.”

Yet many workers are afraid to speak up, fearing they’ll be reprimanded or fired. “People are so afraid,” says Robert Ruth, a black man who worked at the Whitworth Feed Mill in Greenville, South Carolina. “The supervisors talk to the women like they’re dogs. They’ll stand there and cry. I’d try to tell them there was something they could do, but they wouldn’t challenge the supervisors.”

A Cold Shoulder

Outside a typical poultry plant, tens of thousands of chickens sit in trucks, cooled by a wall of fans so the heat won’t kill them prematurely. One by one, they are hung by the feet on a moving line of hooks called shackles and mechanically stunned, decapitated, and scalded to remove their feathers. In a matter of seconds, workers pick off stray feathers, slice the birds open, and scoop out the guts. They then cut the broilers into parts, package them whole, or direct them to a “deboning” line where other workers strip the meat from the bones.

Poultry processing has undergone a dramatic transformation over the past decade. In the early 1980s, giant poultry firms like ConAgra, Tyson Foods, Holly Farms, and Perdue bought up smaller plants, installing expensive automated equipment to kill and defeather the birds. They also added the deboning lines to make new lucrative products — filleted breasts, poultry patties, fast-food chicken nuggets. Between 1975 and 1985, production soared and hourly output per worker increased by 43 percent.

As public demand for chicken has increased, work inside the plants has become faster and more simplified. Job titles sound borrowed from Doctor Seuss: gut drawers, liver pullers, gizzard cutters, skin rollers, thigh bone poppers, lung gunners. Each worker does a single, defined movement — one or two tugs, a lifting motion, the same cut with a knife or big scissors. Some say they repeat their tasks as often as 90 times a minute, 40,000 times a day.

Rose Harrell took a job at the Perdue processing plant in Lewiston, North Carolina, a few months after it opened in 1976. She started as a leg cutter, slicing every fourth bird that came down the line. By 1983, she was expected to cut every other bird — and the carcasses were whizzing by at a faster pace. “When I first went in, the line was going slower, you didn’t have so many birds to kill,” says Harrell, who asked that her real name not be used to prevent reprisals. “Then they started bringing in machines, and everything got faster.”

As the lines moved faster, working conditions grew harsher. “You don’t feel like yourself no more,” says Rita Eason, who went to work at the Lewiston plant in 1980. “They don’t treat you as if you were a person. They treat you as if you were a machine, plugged in, running on electricity.”

Many poultry workers tell stories of working in intolerable heat and cold. Because processing involves both ice and scalding water, temperatures vary from work station to work station. “In evisceration it was about 90 to 95 degrees at all times,” says Donna Bazemore, a former Perdue worker from North Carolina. “In other departments people wear three, four, five pair of socks and long underwear all year. And they’re still cold.”

At Perdue and other plants, scheduled breaks are minimal. Many workers only receive a 30-minute lunch break and two 10- or 15-minute rests each day — but they must remove and clean their aprons, gloves, and boots after the break begins. By the time they wash off the blood and bits of meat, the break is often half over and the few bathrooms are already occupied.

Workers who return late from a break are penalized under a strict point system. Being late — or missing part of a day, regardless of the reason — brings an “occurrence” or a “write-up.” After several write-ups, workers can be “terminated.”

“If you had to go to the bathroom more than once in two or three hours, they would threaten to write you up,” says Brenda Porter, who worked at the Cargill plant in Buena Vista for 12 years. She says the company introduced an even tougher policy last winter. “If you wanted to go to the bathroom more than once a day, you had to tell what you were going for.”

Asked about such restrictions, Cargill spokesman Greg Lauser laughs and says, “I think you’re mixing us up with another company. Employees are encouraged to use lunch and rest breaks, but if there’s a hygienic need to be off the line, we can accommodate that.”

Although it has been nine years since Rita Eason worked at Perdue, she remembers it vividly. “I saw a grown woman stand on the line and urinate right on herself. She was too scared to move. But then she got so cold she walked out and went home.”

Sometimes, workers say, harsh conditions are compounded by harassment. Donna Bazemore says some Perdue foremen told female employees to wear tight jeans and other revealing clothes when inspectors visited the plant. “They’ll say, ‘We want to make him happy so he won’t be stopping the line so we can get these chickens out,’” Bazemore recalls.

Bazemore and others describe rows of women busily working while male supervisors passed by, pinching them or slapping their behinds. It was common knowledge, Bazemore says, that you could get ahead by cooperating.

Risky Business

Perhaps the most serious threat at the processing plants, however, is the risk of disabling injury. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, poultry workers suffer high rates of illness and injury — rates that are more than twice the average for all workers in the private sector.

Poultry processing is “more debilitating than any industry I know,” says Sarah Fields-Davis, director of the Center for Women’s Economic Alternatives, an advocacy group based in Ahoskie, North Carolina. “I have seen women without an arm or fingers, with half a hand.”

Other common problems include warts, skin rashes from the chlorinated water used to wash the poultry, and infections from bone splinters. Workers often lose fingernails and toenails.

“Some people react to the blood in the turkey, and they break out in a turkey rash,” says Tina Bethea, who guts turkeys at the House of Raeford plant in Fayetteville, North Carolina. “Their arm discolors, and they break out in bumps. Sometimes the skin turns black and peels off.”

The most frequent injuries are caused by the speed and repetitive motion of the work. Poultry workers who perform the same task over and over again for hours on end run the risk of developing cumulative trauma disorders — painful nerve and tendon damage that can permanently cripple hands and arms. Found among a wide range of workers from letter sorters to textile workers to typists, the disorders are now ranked by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics as the fastest-growing occupational disease in the country.

The most severe disorder is carpal tunnel syndrome. When the tendons passing through a narrow channel in the wrist known as the carpal tunnel are overused, they swell and press on the median nerve, which controls feeling in the hand. The damage can be painful — and permanent.

Mary Smith worked at Cargill for only seven months, but her brief stint at the Buena Vista plant left her with hands that hurt day and night. A quiet, 41-year-old mother of five, Smith trimmed bruises and tumors from chicken skin. Although her husband worried about her going to Cargill — “he heard people got messed up there” — the job offered higher pay.

“I started working there in March 1988, and my hands began hurting in June,” she recalls. “At first they would swell. The nurse said it was normal; I had to get used to the job. She told me to rub them with alcohol when I got home and put them in hot water. They started hurting real bad and getting numb, especially at night. I’d wake up, shake them, lay them on the pillow. It didn’t do no good.”

Although she has not worked since last September, Smith says, “I still have problems holding things. It hurts to wash dishes, take clothes out of the machine. My arm hurts at night, hurts all day. I get so frustrated sometimes, I feel like just cutting it off.”

Smith is hardly alone. Workers at plants across the South suffer from what many call “ruined hands.” At least 14 of Smith’s co-workers have undergone surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome. Chavulette Jones and Rose Harrell, who both had surgery on their hands after working at Perdue, say they know 14 other women at the Lewiston plant who underwent similar operations.

In spite of her own surgery, Harrell continues to have trouble with her hands. “The numbness is gone, but I’m still in pain,” she says. “Sometimes I can hold things, sometimes I can’t.”

“Take the Pain”

Plant managers for Perdue and Cargill and the owner of the House of Raeford failed to return repeated phone calls to discuss conditions at their slaughterhouses. But Cargill spokesman Greg Lauser says the company tries to educate workers about health risks and takes steps to prevent cumulative trauma disorders.

“We’re like everyone else in meatpacking and poultry,” Lauser says. “We’re on a learning curve, trying to learn about repetitive motion as quickly as possible.”

A Perdue spokesperson refused to answer specific questions, but provided a statement prepared for a June congressional hearing which said, “Perdue believes that some type of responsible industry action should be taken to reduce the incidents of carpal trauma disorders in the workplace.”

The statement then went on to minimize the problem, saying the poultry industry has a cumulative trauma rate “well below the rate for such industries as red-meat packing.” The statement also said there were only 113 cases of carpal trauma among its 12,000 employees last year — “a rate of less than one percent.”

An internal memo from the Perdue personnel department paints a different picture. Dated February 3, 1989 the memo states that it is “normal procedure for about 60 percent of our workforce” at the Perdue plant in Robersonville, North Carolina, to visit the company nurse every morning to get painkillers and have their hands wrapped.

Bill Roenigk, a spokesman for the National Broiler Council, downplayed the role of workers altogether. “Processing involves more automation now,” he says. “There’s a systematic handling of birds and parts.” By the time chickens reach the supermarket, he adds, they are “almost untouched by human hands.”

Rosie Terry is one of 150,000 poultry workers whose hands do touch the birds. Terry, who had surgery for carpal tunnel last year, used to rehang dead chickens on the shackles at the Cargill plant in Buena Vista. When her “hand problems” began, she says, she bounced from doctor to doctor before she was told her condition was work related. One doctor simply said, “I think you’re getting old.”

“He never told me I had carpal tunnel,” says Terry, 51. “I heard it from his wife, also a doctor, who I saw one time when he wasn’t there. He didn’t let me see her no more.”

Terry and other injured workers say they often encounter hostile supervisors, untrained company nurses, or doctors who know little about their medical problems. “When you tell people you’re hurting, they don’t really believe you,” says Perdue worker Rose Harrell. “Talking to one supervisor was like talking to a table. He wouldn’t listen, didn’t care. I told the plant manager that I didn’t mind working, but my hands hurt. ‘What you telling me for,’ he said. ‘I can’t stop your hands from hurting.’”

Such stories are not uncommon. “At Cargill when a worker notices her hands are hurting, she’ll be given Advil and told that she’s just breaking them in,” says Jamie Cohen, health and safety director for the Retail, Wholesale, Department Store Union (RWDSU). “The previous nurse apparently even told some people, ‘Go back and take the pain like the rest.’”

Studies show that ignoring cumulative trauma disorders only makes them worse. Untreated, temporary damage can become permanent, and even a relatively short delay can make a difference.

Companies could help prevent further damage by transferring injured workers to less strenuous jobs. Instead, workers report being assigned to repetitive tasks that only make their injuries worse.

When Rosie Terry returned to work at Cargill several months after her surgery, a supervisor assigned her to hanging chickens and slicing off livers with scissors. She was told to sweep floors only after a doctor restricted her from repetitive work.

Terry was lucky to be reassigned. Even under a doctor’s orders, many injured workers are given some of the hardest jobs in the plant. Dr. Ralph Aguila, who routinely received referrals from Cargill, says he did not have “any problems with the company following instructions” when he recommended a worker for light duty.

Mary Smith tells a different story. She says the company ignored a note from Dr. Aguila restricting her to light duty and put her on the line pulling fat. “I think it was worse on my arm than trimming. I pulled so much fat my nail came loose. My hands hurt worse — it didn’t seem like no light duty to me.”

Blank Logs

Unfortunately, companies have a built-in incentive to ignore injuries — it keeps insurance payments down and saves them from reimbursing workers for their lost wages and medical bills. As a result, workers and union officials charge, companies are trying to cover up the growing number of employees who suffer from cumulative trauma disorders.

Poultry companies are required to report work-related injuries and illnesses on federal “200 logs” filed with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Yet until recently, officials say, most companies have recorded relatively few cases of cumulative trauma disorders.

The disorders “are underreported,” says Roger Stephens, the sole ergonomist at OSHA. “The reporting just doesn’t go on.”

Benny Bishop, manager of the Southland Poultry plant in Enterprise, Alabama, says there are few injuries to report. “Every injury that has been reported has been recorded,” he insists.

Linda Cromer, an RWDSU international representative, says a review of Southland’s logs turned up only 10 recorded cases of repetitive motion injuries from 1985 to 1987, and none for 1988.

But when Cromer and other union organizers visit workers, they frequently encounter injured workers. “We hear about it on every house call,” she says. “People with carpal tunnel surgery are working there.”

In Georgia, the union has filed a complaint with OSHA, charging that Cargill has “willfully and knowingly” exposed workers to jobs “that result in cumulative trauma injuries.”

The complaint also says the company has failed to keep accurate records of cumulative trauma problems. According to union surveys, about 80 percent of Cargill workers report “numbness or tingling in their hands during the night.”

Lauser, the Cargill spokesman, disputes the union complaint, saying he is unaware of underreporting. He says the company tries to keep track of injuries and illnesses “in as straightforward a way as possible, so we can head them off. We encourage them to report any symptoms early and often.”

OSHA has launched an ongoing investigation into conditions at the Buena Vista plant. Yet some observers say the agency has been slow to respond to the cause of the problem — the nature of poultry work itself.

According to Steve Edelstein, a North Carolina attorney who handles compensation cases for injured workers, OSHA rarely looks at the nature of assembly-line work, focusing instead on safety standards and exposure to hazardous substances.

Only recently has the agency started paying attention to the dangers of repetitive motion.

“I think there will have to be limits on the physical demands employers can make of employees,” says Edelstein. “People shouldn’t have to feel pain every day just to make a living.”

Jobs vs. Health

Some say a recent OSHA settlement with Empire Kosher Foods in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, may help get to the root of the problem. Under the agreement, the company must evaluate the effect of posture, tool design, and repetitive motion on each job. The company must also train employees to detect early signs of cumulative trauma disorders and track workers at risk.

Fields-Davis at the Center for Women’s Economic Alternatives in North Carolina cites other changes poultry companies could make immediately. “Redesigning tools and keeping scissors sharp so people don’t have to use their backs to cut doesn’t cost that much,” Fields-Davis says. “Neither does rotating workers” or giving them longer breaks.

The CWEA and unions meanwhile continue to encourage poultry workers to speak out about workplace hazards. Faced with grueling conditions, many poultry workers simply quit. The industry has one of the highest turnover rates in manufacturing — roughly one in 10 poultry workers leave their job each year.

But across the South, some workers are realizing that they should not have to choose between their jobs and their health. In North Carolina, the CWEA is helping workers stand up to Perdue, the area’s major employer. Organizers have offered clinics about repetitive motion injuries and helped hundreds of Perdue workers get medical care and workers’ compensation. Distrust of organized labor runs high in the area, and the women at CWEA say they can reach workers who might not respond to a union drive.

Where unions have successfully organized poultry plants, workers have made health issues a priority. In 1987, the RWDSU organized the Cargill plant in Buena Vista based largely on health and safety concerns. Shop stewards now escort injured workers to the nurse and file grievances over medical problems.

But with fear and intimidation running high, such victories come slowly. RWDSU lost an organizing drive this May at Southland Poultry in Alabama, and the United Food and Commercial Workers lost a recent election at the House of Raeford in North Carolina.

Despite the obstacles, Fields-Davis says CWEA and others will continue to fight for safe workplaces. “We’re not advocating that Perdue leave,” she says. “We just want the company to become more responsive to — and responsible for — the people who are making them rich.”

Tags

Barbara Goldoftas

Barbara Goldoftas, an editorial associate of Dollars & Sense magazine, teaches science writing at Harvard University. (1989)