This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 2, "Ruling the Roost." Find more from that issue here.

In meetings, Donna Bazemore is usually silent — until someone asks her to explain what life is like for a worker in a poultry processing plant. Softly, steadily, and with growing intensity, she tells why people take the jobs, what happens to them inside, and what they can do to get out.

Bazemore should know. She is the first person ever to win a workers’ compensation claim against Perdue for carpal tunnel syndrome, the crippling hand disease. She got a little over $1200 — not much for a single mother of three children. But in the process, she learned a lot about herself, about fear and freedom, stress and self-esteem, and “serving the cause of low-income women.”

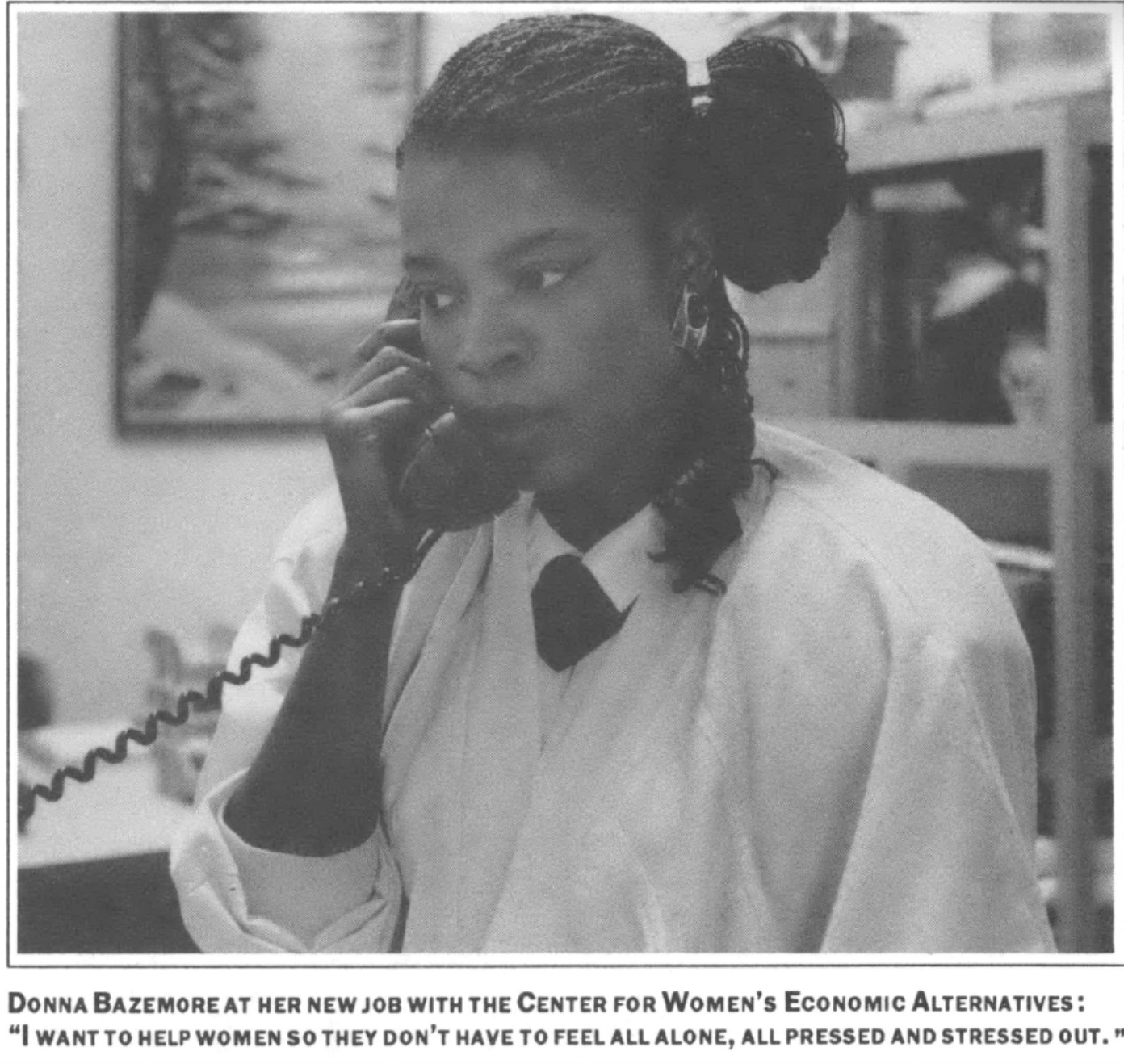

Donna Bazemore is now an organizer with the Center for Women’s Economic Alternatives, based in Ahoskie, North Carolina, not far from her home where this interview was conducted.

My mother was real strong, and she projected all that on us. She didn’t have a lot, and her self-esteem sometimes was really lousy. And it still is. She believes you have to work hard to survive; she expects it to be bad. She will take whatever the system dishes out and say, “Well, it was meant to be this way.”

I think I was the black sheep of the family. I was the one that got into mischief. I was loud. And I always got out of the hard work. My grandparents farmed, and tobacco used to break my skin out.

My uncles and grandparents had big farms in Bertie County, lots of land, tobacco, peanuts, com. Later on, they got into soybeans. My grandfather died, and my uncle took over the farm. But like many black farmers there, they had to stop because it was costing them more than they were actually bringing in.

My uncle is now working at a poultry plant. The farm went under, and now he’s on the saw, cutting chicken breasts. He was the first one I ever heard use the phrase “like a closed-in field” to describe the plant. I call it “a closed-in slave camp.”

Once you walk in Perdue, once you go through the door, everything changes. Your whole attitude. When you come out, you’re like two separate people. It has to do with the stress and pressure they put you under. The treatment. People like my mother have been working in the plant for 15, 20 years. And they bring in kids fresh out of college or high school, white kids, and they make these young white men the foremen who tell her what to do. And here’s she been in that plant, and knows everything a chicken ever had to offer you.

I didn’t see making a career out of Perdue. When I was in high school, I said, “As soon as I get out, I’m going into the Army.” And I’m going to do this, this, and this. I had all these dreams. Then I had this baby when I’m 17.

Hard balls was coming at me, one obstacle after another — things I brought upon myself by not being obedient. You feel trapped into doing what you think is best. So since I had this baby, I thought I should marry her father. And that was like jumping out of the pot into the fire.

I left my mom’s house and went to my husband’s house, and I had not yet found my identity. And I also had this total attitude that I didn’t grow up with my father, so I’m going to make damn sure that my daughter grows up in a house with her father so she can have all the things that I never, never had.

So I stayed in an abusive relationship for a lot of years, a lot of years. Mental and physical and verbal. He would come home and take out his anger on me. I always felt it was something I had done, that I was doing.

Finally, I asked myself, “Did God really put me here to be miserable?” When I was going through all this, I had no self esteem, no sense of being motivated to do anything. I was like his possession. So I sat down one day and wrote out on a paper, “How Do I Build My Self Esteem?” It was like a memo to myself. I got the idea from watching a motivator on TV.

You have to constantly tell yourself, “You are somebody.” Look in the mirror and say something positive about yourself. I’d look and say, “Gee, you got a big nose, but it’s cute!” And I began to make sure that I’d say something positive to myself and my daughters, every day, two or three times a day. I also read a lot of articles in Essence and Ebony about women who have done this or that, and it’s very motivating to me.

When I got out of that marriage, I thought I could do anything. Because it took a lot for me to leave. My mom thought I should stick it out with him. I think she was afraid I couldn’t raise the kids on my own. And neither did I, so she wasn’t far off. But she told me it was totally up to me. She taught us, “If you make a mistake and fall on your face, I’ll be there to assist you to get up, but I will not get you up.” And that makes sense to me.

My mom also left it up to me if I wanted to work at Perdue, but she never wanted me to work there to begin with.

She’s really glad that I came out.

I went to Perdue to buy a dress. I was still married then, in ’83, and I went to get one paycheck to buy this dress. My daughter had a play she was in, and I needed a new dress to go see her. After that paycheck came in, I said, “Wow, I got money! This could be real useful.” And so I stayed on. And then I just got settled back into working.

I liked the money, but I hated the job. My first job was at the rehanging table. The chickens fell on the table and I said, “OH MY GOD!” I could not believe all those chickens! My eyes went together. I got dizzy. And I got sick. I threw up.

The man told me, you pick up the chickens at the back and flip them over so the feet slap against the shackles and they catch. You use both hands, just hang them on the line. Well, the blood was gushing all over my face as I hung them up, and I was trying to wipe it off. He says, “We don’t have time to be cute, Miss Bazemore.” And I was spitting all over the table. Finally, he says, “I don’t think this job is for you.” And I said, “You got that right!”

But I stayed on that job for about six weeks. Both hands are just going constantly — it’s a rhythm you get into — 72 birds a minute. You can actually do it with your eyes closed after a couple of weeks. I actually would sleep doing it, it’s so boring and so hot. You’re right after scalding, and all that heat is coming at you. It’s at least 95 to 100 degrees.

I did everything on the eviscerating line. I began to open chickens. I had to stick my finger in that chicken butt hole and cut down the sides. And I was cutting my fingers because you have to work so fast. I got this scar from opening. And this one from cutting hearts and livers.

I kept complaining and they moved me to trimming. I did that for about a year. And I really liked that. I worked with a good inspector, a young white guy named Cliff. He’d point to the bad part of the bird, and my job was to cut it off. Tumors, bruises, skin diseases, sometimes the chicken head would still be on. He was sympathetic and basically helped me do my work.

I was depressed. I had tried to go to college at nights. But that was just too much on me, so I had to quit. I wanted to go back, so I asked personnel if I could work nights so I could go to college during the day. When I transferred to nights, my grandmother kept my baby daughter and my oldest was in school. And my mother kept them at night.

I went to school from 8 to 12 noon, some days ’til 2. And I worked nights from 10 ’til 6:30 or 7 the next morning. I’d come home, shower and go to school. Some days, I couldn’t even shower. I had to be in school at eight o’clock. Things were tight here, with so little money, and I had not yet learned to budget. So I began to go back out to Perdue at one o’clock and work ’til 4 or 5. And then I would come back home, and go to sleep, get back up at 9, and go back to the plant.

I did that a couple of months. In the day, I was working with Cliff. At night, the inspector’s name was Harold. This was during the time when I was having serious problems with my hands. So I couldn’t keep up, and that really aggravated this man — to keep stopping the line for me. I couldn’t trim the birds fast enough, and I would have to run around the line to get them. And when he would say something to me, I would say something back.

Every time I’d say, “My hand hurts,” they’d give me three or four pills. I knew what an Advil was. But these other ones had no name on them. And it got to the point that I was happy to go to the nurse’s station to get piped up so I could do this work and totally disregard the pain. I didn’t know what I was taking.

I couldn’t squeeze my hand. I couldn’t zip up my pants. And this was before the disease had really affected me. I couldn’t work the lock on this screen door, using my two fingers. I felt like cutting through chicken bone should have made me stronger, so why am I having problems zipping up my pants?

I went to the doctor’s office and I started to read up on carpal tunnel syndrome, tendinitis. I learned you could actually lose the use of your hand. And if I lost the use of my hand, I’d be left to sit around waiting for a welfare check. I couldn’t see that. And I can’t raise my kids on that kind of money. I just kept thinking of that and focusing on what I had to do. I had to raise hell about my hands. I had to overtalk management, because they would try to talk you into thinking that you don’t even hurt, that you’re just imagining.

It got worse when I went to night shift. I couldn’t open my car door or turn on the ignition with my right hand. Sometimes it was so bad, I would get up, shower, and get out of here and my hands would still be asleep. I’d hold this right hand up on the steering wheel and shift the gears with my left hand.

When I got to work, I’d get my hand bandaged. You almost had to stand in line and wait to get into the nurse’s station to wrap your hands with Ace bandages. Some women would take big bundles home and wrap their hands on the way to work. Some would buy them from stores. There are very, very few people that I know on the eviscerating line that don’t have a problem with their hands.

The nurse at this time was a man. And he gave me a hard time. And I gave it right back. He told me one night, “Why don’t you just quit?” And I said, “Why don’t you just marry me and take care of me.” He said, “You think you’re so smart and cute.” And I said, “Man, you don’t know horseshit about me.”

Well, he reported that to personnel. He said I was rude and obnoxious. And they called me into Bill Copeland’s office, the plant manager, and they had three or four plant supervisors there. And they told me what they were going to do, and what I had to do. It was like they thought they were the sperm that I came from. They actually feel like they own you. It just made me remember, I’m living in the days of slavery all over again. They just took me out of the field and put me in a building.

The next morning, Cindy Arnold and Beulah Sharpe came knocking on my door. I saw this white woman and black woman, and I thought they’re selling insurance. I didn’t want to listen to them, but I wasn’t rude so I invited them in. Cindy told me about the Center for Women’s Economic Alternatives, and talked about my rights. They had heard about what I said to the nurse — it got around real fast, everybody in the plant knew about it!

Cindy said that I had the right to file for workers’ compensation and the right to go to my family doctor. So I went back to Perdue and I said, “I need a workers’ compensation claim to take to my doctor.” Bill Copeland said, “We have to make an appointment for the doctor. You don’t need to do anything but get your body over there.” I said, “Wow, this white woman must know some stuff.” He had totally changed. Later that night — at 3 a.m. — he told me I had an appointment to see a doctor in Greenville the next day. So I knew things had changed.

I went to that doctor, he checked my hands, and I went back two days later for nerve tests. He diagnosed me with carpal tunnel syndrome. He put a splint on my hand and told me to wear it for six weeks and it should strengthen my hand. I was still working on the line and the metal in the splint kept pinching my hand. Bill Copeland wouldn’t listen to me, so I went back to the doctor. He wrote a letter saying I should be put on light duty. I was put on the salvage department, and I worked there until it was time to report back to the doctor.

He referred me to another doctor, in Little Washington, and he told me I needed surgery on my hand. I thought it would help but it actually worsened. Now I suffer from a different set of problems — severe muscle cramps, bad throbbing pain in the muscle by my thumb, numbness in my fingers, pain shooting up my arm. When I went back for my last visit, the doctor said, “You have equal strength in both hands.” I said, “But I had more strength in my right hand.” He says, “They told me you were a troublemaker.” I said, “Doctor, I can’t order parts from Sears. All of these parts came with my body, and they’re not replaceable.” He told me the strength would eventually come back even though he didn’t do any nerve tests for the deterioration or anything. He told me I was able to work.

I said he was crazy. I never went back to work after that. I knew that if I had gone back, something would have happened and I would have lost my self control and I would have hurt someone. Because I totally felt that Perdue hurt me intentionally. I felt that there was something that could have been done. The abuse that people at Perdue showed me when I went to them with my problem was unbelievable. And their definition of “light duty” was just stupid. I just think they are unsympathetic people that want to be the slave drivers. They like to feel like “this is my block of niggers and I’m going to whip them into line.” Even when black men come into what little control or power they have at Perdue, they become oppressive. They get the whipping style, too. And I understand that. They want to keep those positions because it makes their life a little easier. And that’s bad.

Several times I stood on the line and said, “If this man says one more damn thing to me, I’m going to stick this knife in him.” That’s how bad it was. You actually felt like killing someone. Women shouldn’t have to work under those conditions, regardless of where it is.

I really want to be able to do something for black women. To help them share their stories so they don’t have to feel all alone, all pressed and stressed out. Let them see that there are other women out here who got beat up, who got put out of their house, who were abused at work. Let them know that there’s someone out here that cares, that will offer support.

I feel what women feel. I know how hard it was — and still is — trying to overcome obstacles that seem to just block your whole path, your whole view. You feel so limited, so afraid.

There is so much fear at Perdue. We were passing out leaflets for the hand clinic, and I heard women say, “Aren’t you scared that the Klan is going to bomb your house.” Or, “Would you tell my story, but not use my name?” They don’t want to lose that job. Or face harassment from Perdue.

One way to deal with that fear is to share stories, and know that it’s okay to be afraid, frightened. It was real intimidating to go to a bunch of white men and say, “I’ve got this problem and your job caused it.” I was scared half to death to walk into this white man’s office that has what I consider to be the keys to Heaven and Hell in his hands.

I go back, because I was raised in the church, to the 23rd Psalm: “Yea though I walk through the shadow of death I will fear no evil, for Thou art with me.” I’ve tried to keep that in focus, that the Lord will be there to provide. I’ve wanted things I couldn’t get, but I’ve never been hungry.

Even if you don’t have a religious view, you can keep a positive dream in view. That’s how books I would read about other women’s stories would really motivate me. Like Sojourner Truth, her life and her sayings. And Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream.” That just stuck in my mind. I have a dream, and now I have to set my goals and objective. I don’t want to settle for what I have caused my life to deal to me. I don’t want to wallow in self-pity. I want to get up and get out and do something, and become this important member of society.

I can’t honestly say that I’m ready to die for the cause of educating and organizing Perdue workers. But I think I am willing to die for the cause of feeling free and having the sense of helping women find freedom. If I can educate this woman about carpal tunnel syndrome and workers’ compensation, and even if she goes back into the plant, at least she knows. She’s free from not knowing; that helps her be free.

I can’t just tell a woman to step out like I did. I can show her the options and get the facts and figures together. I’ll try to steer her in the right direction, but I won’t do all the work for her. She has to take the steps for herself.

That’s one thing the Center imposed on me. “You take on this leadership position. You do this, this and this for yourself.” So I was really educated about the power that anybody has, even low-income women. I found out that if you can talk, you have a lot of power. You can get your message across, open the lines of communication and use them for yourself. I can’t impose my values on someone, but I do want to help people before they get to the breaking point.

Tags

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.