This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 2, "Ruling the Roost." Find more from that issue here.

Atlanta, Ga. — When the national press converged on the city for the Democratic National Convention a year ago, few reporters filed a story without noting the phenomenal growth of the metropolitan region.

The business boom was hard to miss, even for out-of-town journalists glued to the convention floor. New office towers and industrial parks are everywhere. Both the Chamber of Commerce and the state department of industry and tourism publish literature proudly boasting that the northern suburbs of Cobb and Gwinnett counties rank among the fastest-growing in the nation. A popular local joke nominates the construction crane as the official city bird.

From the beginning of the growth spurt in the mid-1970s until last year, everything seemed to be coming up roses for Atlanta. Then area residents began to sniff the local water — and they discovered it smelled like something other than roses.

Last year, Cobb and Gwinnett counties had to impose a ban on sewer connections for all new construction because their waste treatment facilities have reached — or even exceeded — capacity. State environmental officials fined Gwinnett for tampering with water quality testing samples and have refused to permit the county to expand its system because of complaints from downriver residents.

Recent tests showed the waste from Gwinnett’s Jackson Creek sewage treatment plant to be toxic to water fleas and a small fish called the fathead minnow. Further tests are being conducted to determine whether the waste also poses a threat to humans.

Below the city, fish removed from the Chattahoochee River earlier this year were found to contain PCBs and chlordane, deadly chemicals known to cause cancer in humans. The federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has warned residents not to eat fish caught in the Chattahoochee, and the city is working to upgrade its water treatment facility to reduce the amount of phosphate being dumped in the river. Fulton, Cobb, and Gwinnett counties have taken things a step further by banning the sale of phosphate detergents to help curtail the escalating pollution.

“The state is pointing the finger at Atlanta and the metropolitan counties and saying, ‘You caused the problem. You clean it up,’” says Michael Wardrip, chairman of the Georgia chapter of the Sierra Club.

The Boom Goes Bust

What is happening in and around Atlanta should come as no surprise. Rapid economic development has simply followed the all-too-predictable pattern that beset major metropolitan areas in the boom years of the late 1960s — construction, manufacturing, and population growth have spread like wildfire, creating toxic wastes that blacken the water, choke the air, and threaten public health.

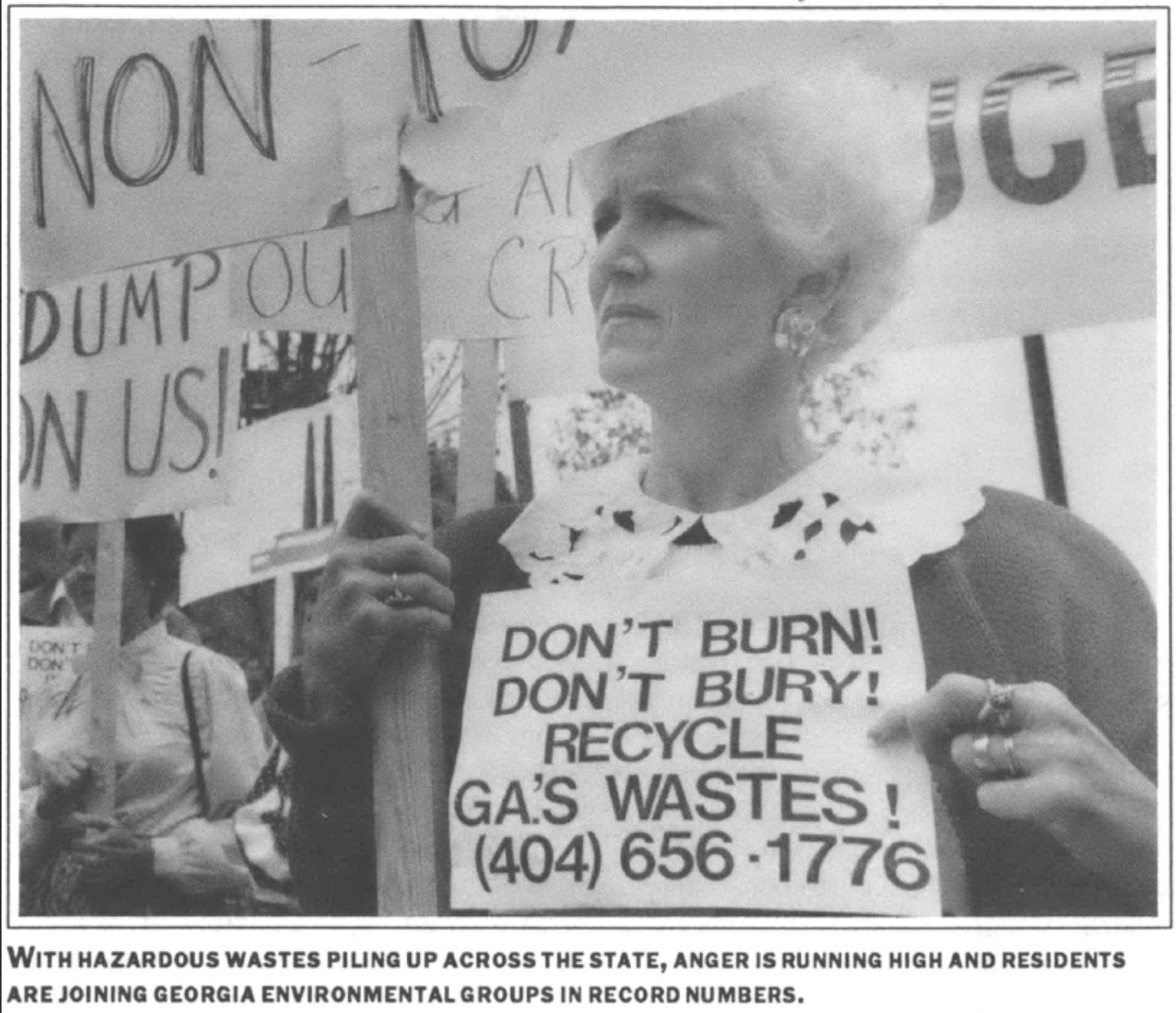

What has surprised residents and local officials is the suddenness with which the environmental dangers have surfaced. Almost overnight, it seems, Atlanta and its neighbors have woken up from a dream of prosperity to morning newspapers filled with stories of contaminated rivers, lakes, and landfills. What emerges is a picture of what can happen when economic development goes haywire — and when outraged citizens join ranks with environmentalists across the state.

“There is no way to express how unfair we think it is to be put at an increased risk and not have any input in the process,” says Debbie Buckner, a Talbot County resident who lives near the proposed site of a hazardous waste incinerator. “My boys are the eighth generation of Buckners to live on this land. I want them to have the same clean environment to grow up in that their ancestors had.”

The pollution doesn’t just come from Atlanta. According to state figures, pulp and paper mills in Chatham, Glynn, and Wayne counties generated more than 90 million pounds of toxic waste in 1987 alone.

The problem has gotten so bad — and the state has done so little to resolve it — that federal officials are beginning to step in. This spring the federal EPA criticized the state, calling its water quality plan too broad and vague to adequately protect water resources. The EPA has threatened to take over supervision of Georgia’s water quality unless the state can meet federal standards. Georgia now ranks sixth in the nation for its level of water pollution. Presently only 519 miles of its 20,000 miles of streams and rivers are classified safe for swimming and fishing.

Upstream from Atlanta, debate has raged for years over the water quality of Lake Lanier, which supplies water for the city and a host of surrounding communities in northern Georgia. The discharge of sewage into the lake from the city of Gainesville combined with unusually heavy recreational use has many residents and scientists worried about the presence of potentially harmful bacteria in the water.

Downstream, citizens are expressing concern about West Point Lake near Columbus, where algae blooms and unacceptable levels of pollutants are threatening to render the important water supply and popular recreation spot unfit for human contact.

The pollution doesn’t stop with the water, either. Atlanta’s air quality regularly falls below federal standards. State figures show that Fulton County, one of the most populous counties in the area, released more than 3.7 million pounds of toxic chemicals into the air in 1987.

“Nobody Would Listen”

The bottom line seems clear: Georgia has failed to calculate the hidden costs of rapid development, and now the state is paying a high price for its failure to plan ahead. Its neighbors are also being forced to foot part of the bill: Atlanta-area industries generate so many hazardous wastes each year that they spill over into landfills in South Carolina and Alabama.

Concerned that nearby states may stop accepting toxic garbage from Georgia, Governor Joe Frank Harris has proposed building a hazardous waste incineration and storage facility in Taylor County, Georgia. Harris insists the facility is vital to recruit more industries and maintain growth, but efforts to obtain a site have been stymied by opposition from concerned citizen groups.

An early effort to locate the incinerator was halted when the courts ruled that Taylor County commissioners had violated state law by failing to hold a public hearing when they decided to pursue the facility.

Although the state selection process was repeated, critics say the state plans to locate the facility in an area that could contaminate groundwater from South Carolina to Alabama. A study conducted by a group of Taylor County citizens also indicated two endangered plant species near the proposed site might be threatened by the hazardous chemicals that would be stored and burned there.

Charging that the state has brushed aside legitimate objections and refused to accept their input in the process, a group of 100 angry Taylor County residents disrupted a meeting of the state Hazardous Waste Authority on April 17. The protesters insisted on time to air their concerns before the panel, but when Governor Harris was unable to silence them, he abruptly adjourned the meeting.

Debbie Buckner, who lives near the proposed site, shouted at Harris for going back on his promise to receive community support before selecting a location. “We could prove our points,” she said after the meeting, “but nobody would listen to us.”

As the battle rages over what to do with hazardous wastes, ordinary garbage continues to present a daily problem in the Atlanta area. As existing landfills reach capacity, metropolitan governments are finding them more difficult to replace. Expansion of the urban population has reduced the amount of available land dramatically, and heated debates often break out when one community tries to open a landfill near the borders of another.

Presently, plans for a Fulton County landfill have sparked a dispute with neighboring DeKalb County, and Cherokee County residents are fighting to block construction of a private landfill which is planning to accept refuse from Atlanta.

The Anger Spreads

Not surprisingly, the mounting ecological hazards across the state have brought new life to the environmental movement in Georgia. Once dismissed as a politically impotent band of outdoors lovers and ’60s hangers-on, the movement now includes a wide spectrum of professions, including developers, bank executives, and teachers.

In the past year alone, membership in the Georgia chapter of the Sierra Club has swelled from 4,802 to 6,240, an increase of almost 30 percent. As a result, the group formed three new local affiliates and has plans for a fourth.

The sudden swell in Georgia membership has been mirrored across the South. In fact, the region is home to six of the 10 fastest-growing Sierra Club chapters in the country — Arkansas, Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina, Florida, and Tennessee. Michael Wardrip, chairman of the Georgia chapter, attributes the Southern growth to a “changing political climate” and a “growing awareness of our environmental heritage.”

“We had a big increase in membership last year during the political season, maybe because both parties were giving lip service at least to environmental concerns,” Wardrip says. “So it became sort of sexy last year for the media to focus on environmental problems.”

The increased media attention has not only boosted the ranks of established groups like the Sierra Club, it has also fueled the creation of brand-new environmental groups. One of the more aggressive newcomers is the Georgia Environmental Project. Founded in 1987, the group made its presence felt almost immediately by organizing grassroots environmental protests throughout the state. The project also joined forces with state workers to win approval for right-to-know legislation that would inform workers of any hazardous substances in their workplaces.

Streamwatch, another new group, has announced plans to monitor pollution in creeks and streams around the state, and a group called Georgians for Clean Water has hired a lobbyist to force the General Assembly to do something about the worsening condition of West Point Lake.

The formation of these new environmental organizations and the increased political clout of the Sierra Club has done more than strengthen the campaign to protect air and water resources: it has also shaken up conservatives within the ranks of the environmental movement. Some of the new activists are charging that the Georgia Conservancy, long the most prominent environmental group in the state, is more of a business lapdog than an environmental watchdog. Although some environmentalists belong both to the Conservancy and to one or more of the other groups, critics charge that the Conservancy depends too heavily on support from major corporations like Georgia Power, Georgia-Pacific, and Exxon, making it a mouthpiece for business interests and softening its stances on important environmental issues.

The Conservancy supports the location of the hazardous waste facility in Taylor County, remained silent on the construction of nuclear Plant Vogtle by Georgia Power, and has issued a study

concluding that acid rain is not a problem in Georgia. Its corporate funding rose 96 percent last year.

“They are heavily influenced by business interests,” says Patrick Kessing, executive director of the Georgia Environmental Project. “The belief on their board is that what is good for business in Georgia is good for the environment, and that’s just not the case. They have gotten themselves in a close relationship with the bureaucrats and find it hard to go against them when the need arises.”

“The bureaucrats” in this case are officials with the state department of natural resources who Kessing and others say have failed to enforce environmental laws. Many want to see the Environmental Protection Division removed from the department, giving the agency more clout and making it more aggressive in defending the environment.

“The department of natural resources has spent 10 years telling everybody everything was OK, when actually everything wasn’t OK and it was getting worse,” says Neill Herring, a Sierra Club lobbyist.

With air, water, and waste-disposal problems pressing state administrators and legislators to some type of action, veteran political observers expect environmental issues to dominate the 1990 legislative session. In counties along the Georgia coast, where sensitive marshes and wetlands have been repeatedly threatened by development, the gubernatorial campaign and key legislative races may turn decisively on concerns over water quality.

All across the state, the new fire in the environmental movement seems certain to keep the heat on state officials. In early June, more than 500 angry Georgia citizens gathered outside the offices of the natural resources department to decry the deteriorating condition of the state’s environment and to call for the resignation of Commissioner Leonard Ledbetter. Organized by the Georgia Environmental Project, the assembly represented more than 30 citizens groups united over the last two years through opposition to local environmental threats.

“The attitude among bureaucrats in Georgia is that we need industry and it doesn’t matter what kind of industry that is,” says Kessing. “People are beginning to understand they can affect that process by organizing and getting involved.”

Tags

Julie Hairston

Julie Hairston is a staff writer for Business Atlanta. (1990)

Julie Hairston is a reporter for Business Atlanta. (1989)