This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 2, "Ruling the Roost." Find more from that issue here.

Detroit, Michigan — Jim Hatfield, a union representative at United Auto Workers Local 735, was catching a lot of flak during a special election last January at the General Motors Hydramatic plant near Ypsilanti, Michigan.

The vice-president of the local had resigned unexpectedly, and competition for the vacant spot was fierce. After all, the winner would be just a heartbeat or another election away from the top.

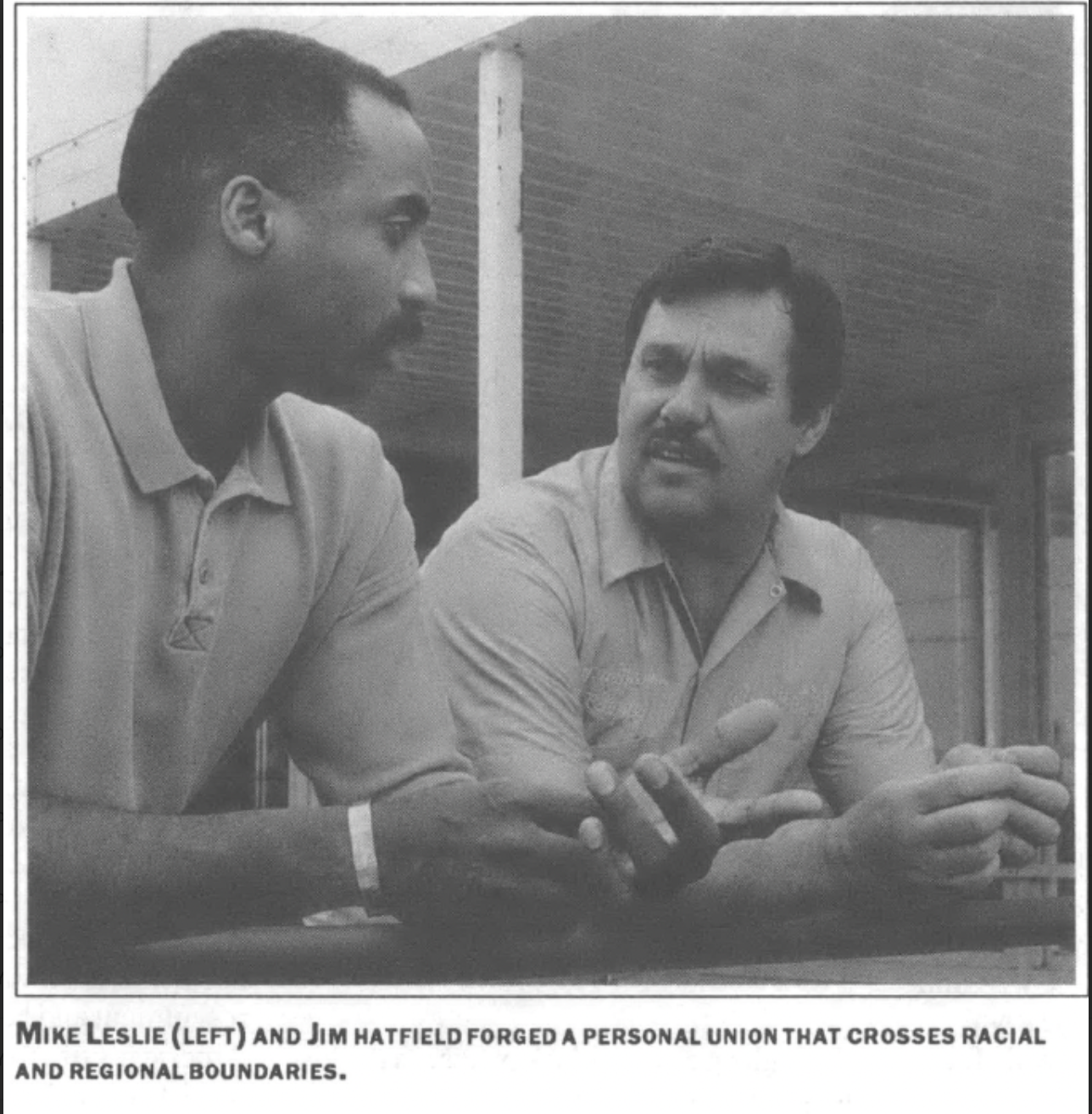

Although the 44-year-old Hatfield is a popular guy in his 1,500-member district — he has held his union post for all but three years since 1972 — he was finding it difficult to convince some loyal constituents to support Mike Leslie for the vacancy.

No one was questioning Leslie’s qualifications. Hatfield had known him for years; they had both served on the shop committee before Leslie became editor of the Local 735 newspaper. Whenever workers needed help in a struggle with the company, Leslie could always be counted on to ask the right questions, report the relevant facts, take revealing photographs, and write a story so everyone in the local would know exactly what was going on.

Still, some workers had their doubts about Leslie. Whenever he was challenged about his support, however, Hatfield displayed the same quiet determination that a long-lost relative named Sid must have shown 70 years ago as sheriff of Matewan, West Virginia, when he sided with striking coal miners against armed company thugs.

The persistence paid off. Mike Leslie, the son of Detroit autoworkers, became the highest elected black officer in the history of Local 735.

And he won with the support of his most trusted advisor and friend, Jim Hatfield, the son of a poor white sharecropper from Tazewell, Tennessee. Even more remarkable, Leslie won in a plant that is three-quarters white, most of whom are also Southern born and Southern bred.

Not quite settled into his new office and trying to carry on a conversation between phone calls and people popping in for advice, Leslie still hadn’t come down from his election-night high. “I’m just amazed that I won. By all rights, you could say that I shouldn’t have. Especially when you analyze the numbers.

“We have about 6,500 members here at Local 735. Of that number, I’d say only about 1,500 are black. It’s obvious that if people came out and voted along racial lines then I couldn’t possibly have won. I won because of a lot of white support, including a lot of white Southerners,” he concluded.

Paradise Valley

The personal union Hatfield and Leslie have forged between North and South, black and white, is not uncommon in Detroit. The mass migration of millions of Southerners that began before World War II changed the political and cultural landscape of virtually every northern industrial city. The migrants came in search of work — and in Detroit, the work they found led them to play a pivotal role in the struggle to organize the auto industry.

Those who made the long journey north nearly 50 years ago were greeted by resentment and hostility. At a time when Americans of all colors united in fighting fascist armies bent on world domination, whites in the streets and factories of Detroit were fighting newly-arrived blacks seeking good-paying jobs and safe places to live.

Spurred by the rapid expansion of defense work that converted the Motor City into a wartime arsenal, some 500,000 whites and 50,000 blacks left the South for the promise of high-paying jobs in Detroit.

And there were plenty of jobs to go around. However, there weren’t always enough decent places for new arrivals to live. The proportion of available housing quickly fell from an eight percent vacancy rate to less than one percent. Consequently, Southern migrants often found themselves squeezed into welfare shelters, empty storefronts, and temporary barracks.

In 1940, a summer camp owned and operated by Henry Ford stood next to the tiny Willow Run stream where the GM Hydramatic plant towers today. When the federal government began looking for a place to build B-24 bombers for the Army Air Corps, they made a deal with Ford to put up a gigantic, mile-long building on the campsite.

Camp Willow Run was gone for good, but thousands of Willow Run workers found themselves camping out in tents, shacks, and makeshift trailers along roadsides and in open fields near the plant.

Some of the newcomers settled in the nearby town of Ypsilanti. Long-time residents deeply resented the influx of blue-collar, Southern white Democrats into their prim, conservative Republican community. Rather than putting out the welcome mat as their contribution to the war effort, they hung “No Southerner” signs on vacant houses and apartments.

In his book Working Detroit, labor historian Steve Babson quotes a state welfare official at the time who spoke about the town’s long-term residents. “The children hear their parents refer to the newcomers as ‘hillbillies,’ trash and the like. Soon they themselves catch this bitter resentment, and juvenile gangs attack and beat up the children of the newcomers.”

Most of the 42,000 workers at the bomber plant, though, ended up living in Detroit and commuting six miles or more each day. Commuting became so troublesome and time-consuming that the plant failed to meet its production quota of 432 planes a month, however, and the city quickly constructed the state’s first expressway to bring workers from Detroit to the plant’s front gate.

While the logistical problems of plant construction and transportation were easily resolved, the city couldn’t manage to build housing fast enough to accommodate the huge demand. Instead, housing projects were quickly thrown up across Detroit.

Competition for the new housing was compounded by the city’s decision to designate projects as black or white. The city’s black population was largely restricted to a 30-block section ironically called “Paradise Valley.” Between 1940 and 1950, the already overcrowded district nearly doubled in population from 87,000 to 140,000.

On February 27, 1942, when one black family attempted to move into new government housing in a Polish neighborhood, they were met by an angry mob of 1,200 whites. A cross was burned in a nearby field. Ironically, the housing project was named after the great black abolitionist of the 1800s, Sojourner Truth.

Jim Crow Up North

With the war creating a severe manpower shortage in defense plants, blacks and women hoped to find good-paying jobs for the first time. To ensure that defense jobs were filled, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order banning all discriminatory practices in hiring and promotions.

Nevertheless, out of 185 defense plants in Detroit, 55 hired virtually no blacks. In most others, black workers were confined to tasks whites refused to do, such as custodial or foundry work. Despite the presidential order, black workers still had to resort to mass walkouts at Chrysler, Hudson, and Packard to assure its enforcement.

However, when three blacks were promoted by seniority at the Packard foundry on Detroit’s east side, 25,000 white workers walked out in protest. Hoping to inflame the situation even further were hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan, the Nazi-front National Workers League, and the fire-breathing fundamentalist preacher, the Reverend Gerald L.K. Smith of Louisiana.

Leaders of the United Auto Workers responded by calling for equality and solidarity. John McDaniel, chairman of the local union bargaining committee, announced in no uncertain terms that the local leadership was “solid in its position that the whites and the colored race were going to work based on seniority and equity of jobs.”

But at a mass union meeting held during the white protest, UAW International President R.J. Thomas was heckled and booed when he urged members to return to work. In a desperate appeal to the strikers Thomas declared, “This problem has to be settled or it will wreck our union.”

In his history of Detroit, American Odyssey, Robert Conot commented on the changing racial relations taking place during the war years. “Southern whites expected Negroes to take back seats. They could not understand how ‘inferiors’ might have better jobs and higher economic standing than they.”

Babson, a professor at Wayne State University, makes a similar point. “For Southern whites, in particular, the union movement’s repeated calls for solidarity between the races seemed abstract and alien.”

“Stop the Line!”

As the union struggled to integrate the workplace over the years, however, many white Southerners took the lead in stressing the importance of solidarity.

Jesse Gregory left his family farm in Red Boiling Springs, Tennessee to work in the Ford stamping plant in Cleveland before finding his way to Detroit. Sitting in his office at UAW Region 1A headquarters, surrounded by photos of his 26 years as a union man, the 54-year-old Gregory reflected on efforts to unite black and white workers.

“Look at that UAW logo there,” he said, pointing to a sign on the wall. “We are all holding hands, black and white, men and women, everybody together. I think the union has done a lot to break down the barriers between us.”

Many Southern whites who hold key positions in the UAW structure share Gregory’s view. Bill Casstevens, financial secretary of the international union, worked in a North Carolina textile mill at the age of 14. Art Shy, retiring this year as director of the union’s education and job training programs, was born in Kentucky and raised across the border in Ohio.

Even Walter Reuther, the legendary organizer of the union and fiery civil rights activist, was a Southerner. The son of a West Virginia brewery worker, Reuther grew up in the industrial city of Wheeling before moving to Detroit. He brought with him a strong strain of social unionism that viewed union members not just as workers, but as parents, consumers, taxpayers, voters, and community members.

Most of the transplanted Southerners who came North to find work and found a home in the UAW shared Reuther’s strong community values, but had little or no previous experience with labor unions. Peggy Cox, a union leader at the GM Hydramatic plant who campaigned for Mike Leslie in the recent election, was a 29-year-old mother and former bank employee when she came north from Bristol, Tennessee. Although she has served as recording secretary at Local 735 for 11 years, Cox came from a part of the country where, she says, “unions were practically unheard of.”

“When I got hired in at Hydramatic in 1966, I didn’t even know what a union was,” she admits. After three days on the job, though, she learned from personal experiences what unions are all about. “The first job they put me on was inspecting transmissions after they were all assembled. They gave me three sheets of paper with all the things I was supposed to visually inspect.

“There was so much to inspect—and they were coming off the line at about three transmissions per minute — that I apparently missed one bolt that had not been tightened down. Well, this foreman, he was one of them old-time, slave-driving, kick-’em-in-the-hind-end kind of foreman. Well, he came running out of the test room yelling and waving his arms, ‘Stop the line, stop the line and get this bitch out of here.’”

With a manner of speech as neat and precise as her hairstyle, Cox continued her story. “Well, I never had anything upset me so bad in all my life. Here I was a mother, a good wife, went to church all the time. I just couldn’t imagine anyone talking to me like that. I was shaking and crying so badly that this union committeeman came over to see what was the matter.

“He came up to me and told me, ‘Lady, you don’t have to take this,’ and then he got into a confrontation right there with that foreman. That day was when I learned what unions are for.”

Jesus and John L. Lewis

Despite their lack of union experience, many Southerners who made the trek north brought deep-seated values that attracted them to the labor movement. For Steve Wyatt, the boyish-looking financial secretary of Ford Local 600 in Dearborn, Michigan, the path to union leadership was marked by the religious training he received as a child.

Raised in a Baptist family that migrated from Arkansas after World War II, Wyatt talked about how Christianity and unionism share a common bond. “I always had this sense of fairness. I was raised with it like many Southern people are. I think it mostly comes from really believing in things like the Golden Rule, that is ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’ I try to live by it and it guides me today in my union business.”

This sense of fairness caused Wyatt to react to injustices he witnessed while still a young worker starting out at the Ford Browntown plant. “There was this black guy I became friends with, Paul Struggs. I still remember his name. We’d talk and eat lunch together when we were both probationaries. He was really a hard worker, a good worker. Never caused any trouble. Always came to work.

“Anyways, I noticed that every shitty job there was around, Struggs would be put on it. He was getting dumped on real bad by this one foreman. There was nothing Paul could do to please this guy. It just got worse and worse until finally Struggs didn’t come back to work and I never saw him again. I’ll never forget what happened to him. It left an impression on me to this day,” Wyatt said, his voice trailing off.

There were other Southerners, though, whose unionism became instilled in them as children raised in union households in the South. Richard Smith, a 56-year-old district committeeman at the Ford Rouge steel plant in Dearborn, remembers the time “Daddy got into trouble.”

“My Dad had tried to organize the textile mill near our home in Blue Ridge, Georgia,” Smith recalled. “They didn’t win and he couldn’t ever get another job around those parts. We picked up and we moved to West Virginia. He got a job there in the coal mines.”

Smith’s childhood experience with unions left no bitter feelings towards them. Instead, he considers unions as essential today as they were 50 years ago. “What have workers ever gotten that they didn’t go through hell to get? I’ve never seen any company yet that ever gave workers anything just because they liked us so much.”

What Charles Dotson remembers most about growing up in the coal country around Peter Creek, Kentucky were the two pictures hanging on his family’s living-room wall. “There was Jesus and there was John L. Lewis, the president of the miners union, and we were taught to look up to both of them with equal reverence,” said Dotson, a 47-year-old staff member at the UAW Reuther Family Education Center in northern Michigan.

Dotson also suspects that a partial reason for his union activism stems from another Southern root: his hometown of Phelps was simply too poor to build more than one school. “Everybody, black or white, went to the same school,” Dotson recalled. “There wasn’t any other school. We all had to go to school together.”

Deer Hunters and Convoys

The union and the shop floor — not public school and college — were the places where most UAW leaders say their most valuable education took place. Mike Leslie, the newly elected black vice-president of Local 735, talked about the lessons he learned from his campaign. “I was almost terrified about going into certain areas of the plant or to approach certain people who seem to fit certain stereotypes. What I found out was that I had made a lot of false assumptions.

“After I finally overcame my nervousness about going into the skilled trades area, I went away realizing that white skilled tradesmen and black production workers really do have more in common than not. We’re both worried about job security, about whether the plant will still be around 10 years from now, and we’re both concerned about providing a good life for our families.

“Then there was this Hi-Lo driver I ran into. He looked like a deer-hunter type. And I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to introduce myself. I thought, ‘Oh, what the heck’ and I told him who I was. He took my leaflet and said he had always read my articles in the local newspaper and liked them. When I left, I had to admit that I looked at him quite differently,” Leslie confessed.

Leslie had been building alliances with white workers in the plant for years. In 1978, for example, he helped organize a convoy that delivered food and other support to coal miners on strike in Middlesboro, Kentucky. More recently, he and two other union representatives launched an investigation into the high incidence of brain cancer among Hydramatic workers.

Such activism won him the support of Jim Hatfield, the sharecropper’s son from Tennessee who served as his most trusted advisor during the campaign. It was Hatfield who first approached the black caucus in the plant to discuss joining forces in union elections.

“I went to the black caucus and I said, ‘Hey look, all these historic differences between black and white should stop,’” he recalled. “‘It’s not doing any of us any good. We need to set all that aside and start working together.’”

Convincing some white workers to support a black candidate was a bit harder. “Oh, I’m not saying we didn’t have our problems,” Hatfield said, describing the campaign in his usual understated manner. “There’s still an element in the plant who — how should I say this — who don’t like to see things change. I just tried to tell people to forget about the color of the man’s skin and look at his qualifications.”

Hatfield said he learned the real value of union solidarity during contract negotiations five years ago. It was a lesson, he said, that he and others in the union will never forget. “The company was very smart about sizing up the bargaining committee and seeing who they had to take care of,” he said. “The old saying about ‘divide and conquer’ had worked very well for management. But in 1984, the black and white committee members got together and decided we weren’t going to let the company drive that wedge between us any more.

“I’m glad we got together,” he added. “We got the best local contract we ever had that year. And every time we’ve stuck together, it’s been fruitful. By looking out for the needs of everybody, we’ve succeeded in everything we’ve gone after.”

Tags

Sam Stark

Sam Stark is a writer and video producer in Detroit, Michigan. (1989)