This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 2, "Ruling the Roost." Find more from that issue here.

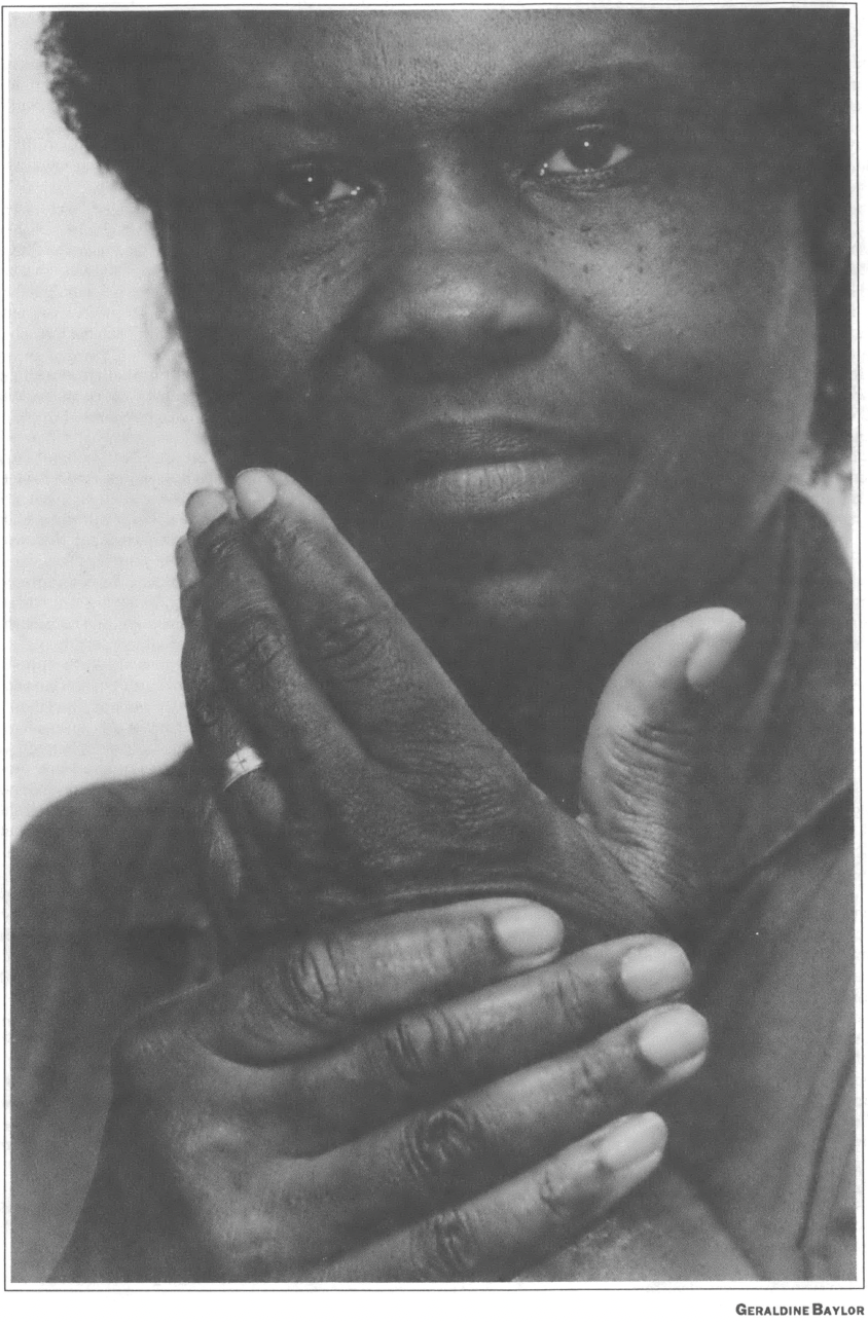

Geraldine Baylor no longer plants flowers.

Warm weather comes, and the beds lie bare outside her one-story, three-bedroom home in Hanover, Virginia. Gone is her stamina for gardening and other springtime chores.

Gone, too, is the job she once held at the Holly Farms poultry plant in nearby Glen Allen. Her life now moves to different rhythms: the incessant throbbing in her left arm, and the painkillers she takes twice a day, without fail.

“One in the morning and two at night,” she explains. “That’s the only way I can get any relief.”

The end to old habits came early last year, when the pain appeared and never went away. Soon, she could barely grasp the chicken carcasses that raced past her on the production line.

Within months she was dismissed — or chose to resign, in the company’s view — from the job she held for nearly 12 years. She never received workers’ compensation. Now, both her health and the perennial burst of color outside her home are dim, disquieting memories.

Her experience typifies the way systems designed to protect workers on the job — and compensate them if they are injured — are failing poultry workers in Virginia.

The state’s chief guardian of workplace safety, the Virginia Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), is only beginning to monitor — much less stop — cumulative trauma disorders, the painful tendon and nerve problems caused by repeating the same tasks for hours on end.

Yet as reports of these illnesses, also called repetitive motion disorders, continue to rise, few workers receive adequate compensation for their injuries. In fact, attorneys and state officials say, opposition by poultry companies and narrow state regulations are making it harder than ever to win compensation.

“Daggone Primitive”

Workers, attorneys, and labor representatives all identify the hand and wrist disorders as the leading health problem in Virginia’s poultry industry, which ranks sixth nationally in turkey production and tenth in producing meat chickens or broilers. They agree that the state’s response to the problem has not only been inadequate — it has made the situation worse.

Even Charles Harrigan, an assistant commissioner for occupational safety and health, acknowledges that state enforcement has not kept up with the number of injuries. “I’m sorry we’re so daggone primitive,” Harrigan says. “We haven’t had a lot of experience, to be quite honest, in addressing cumulative trauma problems.”

State OSHA officials are now giving their inspectors additional training, he says, and plan to begin more aggressive enforcement within a year.

Those officials and others are grappling with a problem that has become the nation’s leading cause of job-related illness.

In 1987, cumulative trauma disorders made up 38 percent of all occupational illnesses reported in private industry, according to a U.S. Department of Labor survey released this spring. The survey concluded that the diseases struck four of every 100 workers in meatpacking and poultry processing, twice the rate reported in any other industry.

In Virginia, cumulative trauma disorders were also the leading cause of occupational illness in 1987, representing almost a third of the 2,812 illnesses reported in private industry.

But many workers and their advocates claim those statistics are greatly understated. They say poultry companies routinely fail to report diseases on OSHA logs, and many workers suffering from carpal tunnel syndrome, tendinitis, and other cumulative trauma disorders either quit without fighting for compensation or simply do not report their problems, fearing they may be fired.

Those who do speak up run the risk of losing their jobs, according to union officials in Virginia and elsewhere.

Company officials deny it happens. But there is nothing in Virginia law to prohibit the dismissal of employees who can no longer perform their duties.

Let go in such circumstances, poultry workers, many of them poorly educated black women, face the difficult task of finding other employment when their most valuable tools — their hands — no longer work well.

For those suffering work-related afflictions, workers’ compensation is designed to provide some relief. But despite frequent complaints of cumulative trauma disorders in poultry production and other industries, a relatively small number of Virginia workers receive awards.

Last year, just 292 workers with cumulative trauma disorders received compensation in Virginia. Carpal tunnel syndrome accounted for 259 of those illnesses — an “absurdly low” figure, says Barry Stiefel, an Alexandria attorney specializing in workers’ compensation.

Private firms paid those employees a total of $575,676 in medical and compensation benefits last year — an average payment of only $2,000 for workers crippled by repetitive, assembly-line motions.

Data on compensation rates for cumulative trauma disorders in the poultry industry have not been compiled. But attorneys say they are winning fewer poultry-related claims than in the early 1980s because the state has gotten tougher on injured workers.

“I handled three cases last year for poultry,” Stiefel says. “In the past, it was not unusual to handle a hundred.”

William Yates, a state Industrial Commission official who has arbitrated thousands of workers’ compensation claims, agrees that the standard of proof needed to win cumulative trauma awards has become more stringent.

For poultry workers, the bottom line is that protection on the job often seems inadequate and workers’ compensation difficult or impossible to obtain.

Token Penalties

The first line of defense for workers on dangerous jobs is the state OSHA program. It began in 1976, six years after the federal agency was established by Congress. Virginia is one of 25 states and territories that has devised its own program by agreeing to adhere to standards set by the federal government.

With a $4.5 million budget, the agency currently has 59 safety and health inspectors responsible for monitoring the state’s 80,000 employers. Officials admit they have trouble keeping up with routine inspections, and high-risk businesses can go three years or more without being scrutinized unless workers complain or the agency hears about a serious accident.

OSHA can fine employers who violate specific safety standards or breach the so-called “general duty” clause by failing to provide a safe workplace. The agency rates violations as “repeat,” “willful,” “serious” or “other-than-serious.”

Although worker advocates say the Virginia OSHA program offers roughly the same protection as its counterparts in other states, statistics suggest that the agency has been something of a paper tiger to the state’s poultry industry, which employs 13,500 production workers.

From January 1982 to May 17 of this year, the agency made only 32 inspections of Virginia’s two dozen poultry plants, according to state OSHA records. Employers were cited for health or safety violations in just 17 of those inspections.

Most citations fell in the “other-than-serious” category; no “willful” or “repeat” violations were listed. There were just 11 termed “serious,” resulting in total fines of $3,580.

Thus, in a period of more than seven years, less than a dozen serious health hazards were found in all of the state’s poultry plants, with an average fine of $325 — amounting to little more than a token penalty.

Some of the most serious problems were found at plants operated by two of the state’s leading poultry processors, Perdue and Holly Farms.

In November 1988, Perdue’s Bridgewater plant was penalized $420 for a serious safety violation after a worker’s foot was caught in a machine. Two months later, the same plant was cited for four other serious violations and fined $1,680.

In 1987, the Holly Farms plant at Glen Allen was cited for two serious and nine “other-than-serious” violations. The total penalty imposed was $500, reduced from an original fine of $810.

Harrigan, assistant commissioner for occupational safety and health, blames the tepid enforcement on a strained budget and the difficulty of linking cumulative trauma problems to the workplace in the absence of specific safety standards.

Federal and state OSHA officials could invoke the “general duty” clause to improve workplace safety, but many believe standards would be more equitable and easily enforced. Whether safety standards can be developed for the poultry industry, where workers engage in a wide variety of cutting and grasping tasks, is a much-debated issue.

“It’s not like walking up and seeing that you need a guard on a saw blade,” says Harrigan, clearly frustrated. “I know more can be done; I just don’t have answers.”

Hassles and Fear

Poultry workers afflicted with the disorders, meanwhile, face mounting obstacles in obtaining workers’ compensation. The situation is especially ironic because the system designed to help them has been in place for years.

The workers’ compensation program began in Virginia in 1919, part of a movement in many states to give injured workers an alternative to civil suits. In Virginia, workers hurt on the job cannot sue, making workers’ compensation their only relief.

Workers suffering occupational injuries must notify their employer and file for benefits within 30 days. Those afflicted with carpal tunnel syndrome or other occupational illnesses must begin the process as soon as a doctor determines that their conditions are job related.

Besides paying for some medical costs, the program partially compensates workers who cannot work at all or must work at lower-paying jobs. Workers also are compensated if they permanently lose some degree of body function, with amounts varying according to the part of the body affected and the degree of disability. For loss of a hand, for example, employees receive two-thirds of their weekly wages for 150 weeks.

But for partial loss of function — a condition typically suffered by cumulative trauma patients — compensation is cut according to the severity of the disability. Poultry workers ruled to have a 10 percent loss of function in one hand, for example, are paid two-thirds of their wages for only 15 weeks.

One of the biggest problems with the program, however, is a lack of information — most workers have simply never heard of workers’ compensation. It is not uncommon, union officials say, for employees to confuse compensation payments with disability benefits provided by company insurance plans.

In unionized poultry plants, workers may learn the difference from shop stewards or union literature. But in plants without a union, posters tacked to crowded bulletin boards may be the only information about workers’ compensation workers ever receive.

Another difficulty for some workers is knowing where to apply for benefits. For years, workers could only file claims in Richmond. Beginning this July, claims can now be filed at branch offices in Norfolk, Alexandria, Roanoke, and Lebanon.

For the poorly educated women who dominate the labor force in the poultry processing industry, writing a letter or making a long-distance telephone call to state officials can be daunting.

“You’re talking about noticing an eight-inch by 10-inch card, the formidable idea of writing, the hassle factor,” says Stiefel, the Alexandria attorney.

Poultry companies have no incentive to promote workers’ compensation because additional claims drive up their insurance costs. “If you don’t say anything about workers’ compensation, they don’t tell you anything,” says Mary Vines, a worker at the Holly Farms plant in Glen Allen.

Still another stumbling block to applying is the fear of reprisal. Although companies deny the connection, accounts of cumulative trauma victims who were fired after obtaining benefits are not unusual.

To make matters worse, Virginia workers who want to file a claim must choose their doctors from a list provided by the company. Choice of physicians varies from state to state; in North Carolina and South Carolina, the employer chooses the physician.

Even if Virginia poultry workers clear all the hurdles in applying for compensation, they still face the strong possibility that their claims will be rejected. Although four out of five claims are uncontested, poultry companies and their insurance carriers “routinely” battle cumulative trauma cases, Stiefel says.

Last year, private firms in Virginia refused to pay 3,700 workers who filed for compensation, forcing the state to hold hearings on the claims.

To counter such opposition, workers typically seek legal counsel to argue their case before a hearing officer. Many lawyers, however, will not represent them.

The reason is money. Attorney’s fees, which are approved by the state, usually consist of a percentage of the award in cumulative trauma cases. If the workers lose, their lawyers often go unpaid.

“The biggest fee I’ve ever received in one of these cases was $1,200 — the biggest by far,” says Kenneth Bynum, a Falls Church attorney who handles poultry cases. “Some are $75.”

“In the Midwest, we’d find that every town had attorneys that would fight compensation cases,” says one veteran union organizer. “In the South, no lawyers represent workers. The fees are peanuts.”

The One Percent

The biggest obstacle to poultry workers seeking compensation, however, may be a recent change in state law.

The antecedents of the change, Stiefel recalls, began early in the decade, when assembly-line speeds as much as doubled and cumulative trauma illnesses began striking poultry workers.

Experts who came to Virginia and began studying the dynamics of motion on the poultry processing line, he says, became convinced the disorders were work related. They communicated their findings to physicians, whose testimony made cumulative trauma cases easy to win — for a time.

“I’d say that our success rate was 90 to 95 percent for hundreds of cases,” Stiefel says.

But all that changed four years ago, when the Virginia Supreme Court heard the case of Brenda Gilliam, who was awarded workers’ compensation after her elbow was injured by the repetitive motion of a telephone assembly line. The court decided in favor of the company, effectively ruling that cumulative trauma disorders are “ordinary diseases of life” — that is, not specifically linked to the workplace, and thus ineligible for compensation.

Attorneys representing workers were shocked by the ruling, but poultry companies hailed the decision. Both sides took the battle to the state legislature. The result was a 1986 amendment that made some cases compensable, but only under a stricter standard of proof that essentially requires physicians to testify that an illness occurred from conditions on the job, and nowhere else.

That is almost impossible for medical professionals to do, because cumulative trauma disorders can result from a variety of causes, or even for no apparent reason.

As a result, physicians who call an illness job-related in private conversation often reverse themselves in testimony, said Don Cash, a vice president of Local 400 of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, which represents poultry workers in Virginia.

“The thing we’re always running up against is the doctors,” Cash says. “They say it’s maybe 99 percent certain that the problem is work related. Then the cross examination comes, and they’re asked, ‘Are you absolutely certain?’ And they say, ‘No.’ It’s that one percent that kills us.”

Between the Cracks

The combination of obstacles keeps many poultry workers in Virginia from ever receiving compensation.

Geraldine Baylor tried. By her account, her chronic tendinitis was undoubtedly caused by her job.

The problem arose early last year, she says, while she worked as a breast cutter, slicing about 15 birds a minute. It was caused, in her view, by exceptionally large birds that appeared on the production line and kept coming for days.

Soon, she noticed the ache in her arm. Her cutting speed faltered, and she went to the company nurse.

“She didn’t want to say it was my job,” Baylor recalls. “She said, ‘Go back and try.’ I’d get back at it. Then they’d switch me to other jobs. Finally in May, it got so bad I couldn’t sweep a floor. I couldn’t do anything.”

She took a leave of absence on May 3, 1988. Company records show she returned October 24, worked for a week, and resigned.

Baylor has a different version of her departure. She remembers working on the line as a packer, a less stressful task, when she was told to return to cutting. She remembers a superior telling her, “‘If you can’t do your job, I’ll give you a leave of absence until you can go back.’ So I never went back.

“I didn’t quit. He just wouldn’t give me nothing else to do. I liked Holly Farms. If I’d stayed there three more years, I would have had some kind of pension. Now that’s gone.”

She says she contacted Kenneth Bynum, the union’s attorney, about obtaining workers’ compensation, but had no success.

“I tried every angle I could think of,” Bynum recalls. “Her medical (evaluation) didn’t back her up. One general practitioner said it appeared to be work related. The hand specialist never said that. It’s a frustration I go through every day.”

A Holly Farms official who asked not to be identified calls Baylor a cumulative trauma victim who “fell through the cracks.”

He concedes that the Glen Allen plant has problems with the disorders, “but no worse than any other poultry or meatpacking plant.”

Parade of Pain

Workers and labor leaders advocate a variety of steps to improve health and safety in the poultry industry (see box). In the meantime, though, the parade of pain continues. Poultry companies keep working faster and faster, trying to beat the competition as they strive to fulfill the national craving for their products.

In Virginia, that competition is likely to increase between Holly Farms, the nation’s third largest broiler producer, and Perdue, which ranks fourth. Second-ranked ConAgra is considering a $1.3-billion buyout of Holly Farms, a move that would increase its ability to compete with Perdue and top-ranked Tyson Foods, says Bill Roenigk, a spokesman for the National Broiler Council.

As demands on the workforce have escalated, however, union membership among Virginia’s poultry workers has declined. The reason? “Most of them don’t know how to fight,” says Stiefel, the Alexandria attorney. “But I don’t believe the problem has abated, not one iota.”

For workers like Geraldine Baylor, permanently crippled by cumulative trauma disorder, the problem will never abate. Yet Baylor was lucky — unlike many injured poultry workers, she was able to find another job. She now works on the production line at a furniture factory, earning slightly less than she did at Holly Farms, where her hourly wage was $5.72.

“I can do the job,” the 48-year-old worker says of her new position. “But when I get home, I have to double my medicine.”

Tags

Joe Fahy

Joe Fahy, a reporter for the Indianapolis News, was formerly a staff writer for The Virginian-Pilot and The Ledger-Star in Norfolk, Virginia. (1989)