The Story in Numbers: What Happened November 8th

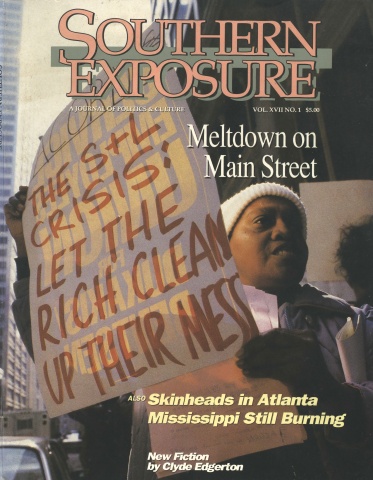

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 1, "Meltdown on Main Street." Find more from that issue here.

On the day that 25 million Southerners went to the polls, Jerry Hombuckle went to the mall.

“I’m not going to vote because it’s all a big game,” said the 23-year-old Durham, North Carolina resident. “I feel like: How vulnerable do they think we are? [The candidates] are not showing me anything. They’re not talking. They’re spending millions of dollars campaigning on something that is like ac hild’s game.

“It’s not that I don’t care. I’m just not going to be a victim of the game. I feel as soon as I go out and vote, they’ve won me.”

Hombuckle wasn’t alone in his decision to bypass the ballot box on November 8. In fact, he was in the majority. Only 45 percent of the South’s eligible voters went to the polls — the smallest percentage of any region in the country. Nationally, only half of all adults over 18 cast a ballot for a presidential candidate.

The South’s below-average turnout continues a tradition that stretches back nearly 100 years. But while low voter participation once favored entrenched Democratic politicians, it now benefits the Republican Party. And it is one of the major reasons the GOP is making such significant gains in the South.

In Mississippi counties that went for George Bush, voter turnout was 60 percent last year. By contrast, turnout in counties that went for Michael Dukakis was a mere 49 percent. That pattern repeated itself throughout the South.

The Vote Stays Home

Ironically, it was the Democrats who — 100 years ago — set the stage for their own downfall in the South. After the Civil War, during the heyday of the Populist-Republican- Democrat contests, Southerners registered and voted in record numbers. But with the rise of Jim Crow laws to restore Democratic control and discourage blacks and poor whites from voting, participation levels plummeted. In every state of the Old Confederacy, voter participation rates were twice as high in the 1880s as they were in the 1940s.

More Virginians cast ballots in the 1888 presidential election than in any year until 1928, when women first voted and the population had increased by more than 500,000.

Now, a century later, the legacy of voter disenfranchisement is coming back to haunt the Democrats. The party’s strongest support in November came from blacks and lower-income whites. But those two groups — whom Southern Democrats have traditionally discouraged from voting — are now the ones most likely to stay home from the polls.

In the six Southern states that maintain records by race, 57 percent of eligible nonwhites are registered to vote, compared to 67 percent of eligible whites. The gap is 8 percent in Louisiana, 9 percent in Georgia and North Carolina, and 15 percent in Florida.

Since the passage of civil rights laws in the 1960s, the percentage of non-voters in the South has gradually come closer to the national average. But it still has a ways to go: Had Southerners voted at the same rate as other Americans, an additional 3.8 million adults — many black and most living on modest incomes — would have exercised their political franchise. As it was, Bush beat Dukakis by only 4.2 million votes in the South.

Low turnout hurt Dukakis across the region. For example, in nearly all-white Shelby County, Alabama, just outside Birmingham, turnout was 69 percent — and Bush racked up 79 percent of the votes. By contrast, mostly black Macon County, home of Tuskegee Institute, gave Dukakis 82 percent of the vote. There, only 41 percent of the county’s voters showed up at the polls.

That pattern showed up all over the South in nine states analyzed by the Institute for Southern Studies, which publishes Southern Exposure. The Institute’s analysis showed that blacks were not the only voters who stayed home election day — poor whites also did.

In fact, whites earning less than $10,000 a year were less likely to vote than blacks of any income group — even those with incomes below $5,000.

Brooks County, Texas, north of the Mexican border, is mostly white — but its share of lower-income families is almost double the state average. That county went overwhelmingly for Dukakis — 82 percent, to be exact But voter participation was only 52 percent — far below the state’s overall turnout figure.

Contrast that to Collin County, in Dallas’ affluent northern suburbs. There, 74 percent of the voters turned out — and the same percentage went for Bush.

Tale of Two Cities

There’s another pattern in which the Republicans can take comfort. Some of their strongest counties — including the affluent suburbs around Atlanta, New Orleans, Birmingham, Nashville, Dallas and Houston — are growing far faster in population than the region as a whole.

In Georgia, the counties that went overwhelmingly for Bush had an average annual growth rate of 3.3 percent, compared to 1.1 percent for the counties Dukakis carried. In Texas, Bush’s strongest counties had a 3.1 percent growth rate, compared to 2.2 percent for the Dukakis counties. And in Mississippi and Virginia, the counties won by the Democrat averaged no growth at all.

Perhaps there’s no better place to see this pattern than in metropolitan Atlanta. That region has grown tremendously — but only in the lily-white suburbs that lay along the perimeter highway that rings the city.

The heart of Atlanta is Fulton County — a mostly black county with more than its share of poverty. Despite Atlanta’s reputation for high growth, Fulton County’s 1.1-percent annual growth rate was less than that of the state as a whole. Dukakis carried Atlanta with 56 percent of the vote.

Around urban Atlanta runs a giant interstate loop, lined with glass and chrome office towers, which divides the metropolitan area by race, class, and growth patterns. Outside Interstate 285, to the east, lies suburban Gwinett County, which is 96 percent white. Gwinett is growing more than five times as fast as Fulton County; few counties in the South can equal its 6.1 percent growth rate. True to expectation, Gwinett gave Bush a decisive 76 percent victory.

With affluent, white, Republican suburbs growing so much faster than the inner cities they surround, the direction of electoral politics in major Southern metropolitan areas should be clear. “Southerners are now looking first to the Republican Party to run the country,” University of North Carolina political scientist Merle Black told the Miami Herald. “It would take a catastrophe — like a war or a foreign policy disaster — to befall the Republicans to shake that experience.”

Apathy or Boycott?

Since the election, Democratic leaders have put the blame for their party’s loss on its liberal image. “We need to get back to the middle, back to the mainstream ,” Senator Charles Robb of Virginia told the Herald just after the election. “We’ve got to project an image that we support a strong, credible, national defense, that we support fiscal responsibility — in addition to talking about and remembering our social responsibilities.”

But most of those leaders drew their conclusions by looking at the citizens who actually voted — rather than the millions who failed to vote because neither candidate inspired them. Those non-voters, largely poor and working class, were looking for candidates to deliver a message of tough economic populism.

Those citizens didn’t stay home because of apathy. Many chose consciously not to vote. In fact, if this were a Third World country, the low voter turnout would have been accurately interpreted as a boycott by half of the voting public.

“I just don’t think either [candidate] is fit for it,” said 53-year-old Doris Craig just before the election. Craig works in the textile town of Spindale, North Carolina, selling yam at an outlet run by one of the local mills. She struggles to get by on her part-time job — and she says neither Dukakis nor Bush addressed her plight.

“I would like to see wages go up, I would like to see the blue-collar people have something, and I would like to see these corporations pay taxes — because there are so many loopholes,” she said.

“We need a good man like Franklin D. [Roosevelt]. We need one like him. He did more for the working-class people than anyone we’ve had. People were out there hungry. They were begging for something to eat, and he put people to work.”

When she listened to Bush and Dukakis “hit one another on the back,” Craig said their rhetoric was far from her own concerns. “I would like to hear them say they would raise the hourly wages, and really mean it and stick to it.”

In the final days before the election Dukakis did exactly that. He abandoned his cautious — some said cold — campaign style, and the strategy paid off. A CBS-New York Times poll showed that six out of ten voters who made up their minds in the week before the election cast a ballot for Dukakis.

“If Dukakis had talked for three months the way he did in the last two weeks, we would be sending Bush back to his summer home in Kennebunkport,” said Texas Agriculture Commissioner Jim Hightower, who is working to build a national populist movement within the framework of the Democratic Party.

Even Lee Atwater of South Carolina, Bush campaign manager and now the chair of the national Republican Party, recognized that the greatest threat to his party is a strong economic message that mobilizes blacks and moderate-income whites. “The way to win a presidential race against the Republicans,” he told The Boston Globe after the election, “is to develop the class-warfare issue, as Dukakis did at the end. To divide up the haves and have-nots and to try to reinvigorate the New Deal coalition, and to attack.”

Courting “Rednecks”

When Democratic leaders call for the party to move back to the “center,” they are often subtly (or unsubtly) calling for their colleagues to abandon their visible outreach to blacks — in order to win back some conservative Southern whites. In North Carolina, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Bob Jordan made that very clear when he told a group of Greensboro black leaders: “There may be some programs . . . I believe in that will not be campaign issues, because if they are, I won’t be governor.” Jordan told his audience that he didn’t want to alienate the eastern North Carolina “redneck” vote.

If the Democratic Party follows that course — of abandoning blacks to pursue white “rednecks” — it will be abandoning its most faithful constituency. In Tidewater Virginia, blacks voted overwhelmingly Democratic in November — even though black Republicans were running for Congress.

“I’m a Democrat all the way,” Norfolk voter Alice Beckham told the Virginian- Pilot. “That won’t change. Democrats have done more for me. If a Republican’s in there and you’re poor, you’re going to end up poorer.”

Her neighbor, Lillian Coleman, agreed. “I always vote Democratic. I like the way they act in office. They stand more for what I believe. I’ll vote the party before I vote race.”

If Democrats want to win, they need to build on this support by articulating a vision of the benefits of racial solidarity. They must emphasize issues that can unite blacks and whites, such as economic justice, quality education, and community health. The results of five of the last six presidential elections show that the Democrats can’t win by shying away from race — or by trying to out- Republican the Republicans on black-white issues.

The Democrats actually appeared to be trying to distinguish themselves from the Republicans in February when they elected Ron Brown as the first black chair of the party. Brown said the party must unite disenfranchised voters with whites who have abandoned the Democrats. “It’s obvious the center is crucial to Democratic victories,” he said. “We’ve got to reach out to new voters. We’ve also got to reach out to voters that we lost in recent Presidential elections.”

If it doesn’t act soon, the time may be coming when the Democratic Party will lose the near-unanimous loyalty of Southern blacks. In Mississippi, Republican Senator Trent Lott fared well in the predominantly black 2nd Congressional District, trailing Democrat Wayne Dowdy by fewer than 10,000 votes. Early in the campaign, Lott predicted his emphasis on jobs and education would win black support.

“I think what we are seeing is a genuine two-party system,” Lott said after his victory. “We are not going to let it get into a black-white thing.” Lott promised to work to tell “young, minority, professional men and women [that] what we are talking about is economic development for you and your children. Give us a chance, and don’t be married to one label or the other.”

Tags

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.

Barry Yeoman

Barry Yeoman is senior staff writer for The Independent in Durham, North Carolina. (1996)

Barry Yeoman is associate editor of The Independent newsweekly in Durham, North Carolina. (1994)