This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 1, "Meltdown on Main Street." Find more from that issue here.

Atlanta, GA. — Before she leaves work each afternoon, Patty Lichter checks the local entertainment guide. If she sees notice of a nearby performance by one of several touring punk bands that night, she makes sure she has plenty of glass cleaner on hand, because she knows when she gets to work the next morning, her shop windows will be covered with spit.

“It’s almost like a game,” she says off-handedly.

Lichter owns a store called Gear in the Little Five Points shopping district. The trouble started about a year-and-a-half ago when she ordered some t-shirts with Cyrillic lettering from a distributor in London. After she put the shirts on display, her store became a favorite target for vandalism by the gang of neo-Nazi Skinheads who hang out in Little Five Points. To them, the Cyrillic lettering marked her store as a “communist” outlet.

Before she finally purchased a $1,200 steel pull-down door to cover her storefront at night, she lost three $500 display windows to Skinhead violence. Now that the Skinheads can no longer smash the windows in their drunken rampages, they simply walk by and spit on the glass through the steel bars. Lichter shrugs it off with a boys-will-be-boys nonchalance.

“We have sort of gotten used to it now,” she admits. “They would apparently come by our windows, [see the tshirts] and smash them. It became an excuse for them to do what they like to do, which is to get drunk and go out and get in trouble.”

A Shadow Over Atlanta

The Skinhead presence in Little Five Points is an irony of sorts. While the community has been fabled since the ’60s as a haven for peaceful coexistence among an eclectic mix of racial and philosophical sects, the Skinheads who more recently have adopted it as a hangout are known for their violent supremacist ideology. Along with their shaved heads and laced, shin-high boots, the Skinheads have adopted an aggressive, racist nationalism that has made them the fashionable new darlings of the ultra-right.

From their first appearance in Little Five Points more than three years ago, the Skinheads have shattered the serenity of the neighborhood. In 1985, a gang of Skinheads angered at having been ejected from an Atlanta nightclub for their rude and disruptive behavior attacked the club owner in the parking lot with sticks, bottles, and boots. Their victim was hospitalized. Later that year, a gang of Skinheads crashed a fundraiser for Nicaraguan relief, intimidating guests and overturning tables. When an organizer tried to flee, they beat him unconscious.

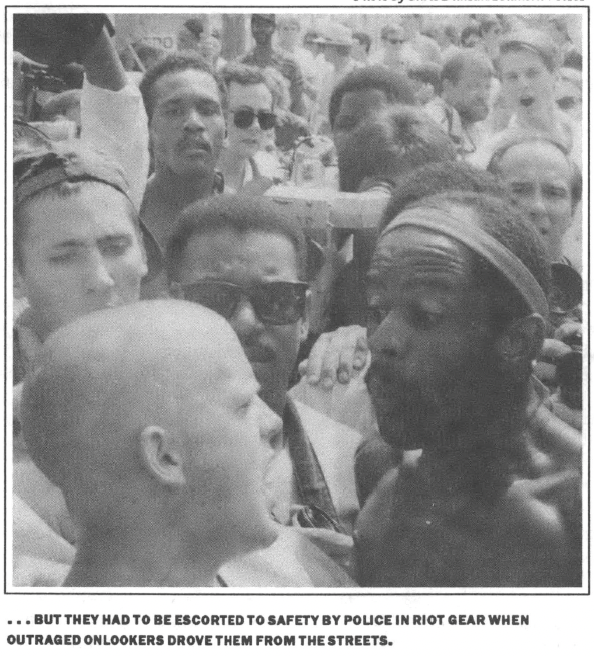

Today, Skinheads in Atlanta number more than 100, and they continue to harass and attack anyone who gets in their way. A group of Skinheads staged a protest downtown at the Democratic National Convention last summer, but they were driven from the street by outraged onlookers and had to be escorted to safety by police in riot gear.

Although the Skinheads continue to cast a long shadow over the Little Five Points community, nobody is willing to confront them directly. Merchants tend to downplay the trouble, fearing that reports of violence will drive away some of the hundreds of customers who come to Little Five Points every weekend to eat, drink, and shop. After all, they say, they don’t want to harass anyone for looking “different.”

“We live with the people who live here however they want to dress,” says Bill Carmichael, owner of Abbadabba’s, a clothing and jewelry store, and president of the Little Five Points Business Association. “Little Five Points has gotten a reputation because we tolerate a lot down here. This, too, shall pass.”

For now, residents continue to live in fear and look the other way. All the business association has done so far is to hire extra security patrols for the neighborhood.

The Violence Spreads

What is going on in Little Five Points mirrors communities across the South. In town after town, small gangs of Skinheads have begun to surface — from Covington, Kentucky to Fort Smith, Arkansas. Most are teenagers, and most preach white-supremacist hatred, vowing to terrorize blacks, Jews, and homosexuals.

As in Little Five Points, the emergence of the Skinheads has been marked by violence. In 1987, a pair of Skinheads from Tampa, Florida bludgeoned to death a black man they found sleeping in a doorway. In January, a Skinhead in Dallas was sentenced to 10 years in prison for vandalizing a synagogue.

Older, more established white supremacist groups like the Klan and Aryan Nations see the Skinheads as a useful vanguard. Rebellious teens who emulate the look often are pressured by more ideologically oriented Skinheads to assume the “correct” philosophy as well. Efforts to organize Skinheads nationwide have taken on sophisticated techniques ranging from newsletters and local rallies to war games and a national convention.

The success of such organizing efforts has been mixed, according to the Center for Democratic Renewal, an Atlanta-based group that monitors white supremacist violence. The CDR reports that the Skinhead ranks nationwide have swollen from 300 in 1986 to 3,500 today. For the most part, Skinhead violence remains random and independent, but CDR officials say they are wary of organizing efforts now being mounted by more established groups whose membership has been on the decline in recent years.

“The radical right sees the Skinheads as the hope for the future of America. They are certainly trying to organize them,” explains Eric Anderson, an anthropologist from Washington State University who studied a group of San Francisco Skinheads. “So you get Skinheads carrying business cards openly, trying to recruit kids at dances and concerts. They are being used by these organizations to recruit new members.”

Although the first Skinheads who emerged in England 20 years ago were products of a working-class resentment toward West Indian and Pakistani immigrants, their American counterparts have succeeded in recruiting from the middle and upper-middle classes as well. Anderson says that young suburbanites are sometimes drawn to the Skinheads by a yearning for a rebellious identity not satisfied by homogenized suburban culture. “People are always looking for roots somewhere, and they are not getting it in the suburbs. I guess that’s why the Skinhead movement has caught on here far more than I thought it would.”

Patty Lichter echoes that observation. “These kids are too fashion-oriented to be working class,” she says of the Skinheads in Little Five Points. “These are kids that are at least middle class. It is not a joke that at the end of the day they get into their parents’ BMWs and drive away.”

While Skinheads in England joined the neo-Nazi nationalistic movement there, many Skinheads in the United States have blended elements of white supremacist rhetoric with a smattering of traditional, white Republicanism. The result has been a hyper-American band of racists who shave their heads and want to beat the living daylights out of anyone they perceive as a threat to their brand of Americanism. One group of Skinheads even proposed a political platform that called for making Ronald Reagan “leader for life.”

Beer and Pizza

On a typical Saturday night in Little Five Points, a group of duly shaved and booted Skinheads gathers in the plaza between The Point and the Little Five Points Pub. They toss back great gulps of beer from the cooler in Fellini’s, a low-key pizza joint facing the plaza, and swagger about for the gawkers. The weather is unusually warm for this time of year and the district is appropriately lively with music and the usual mix of strollers.

The Skinheads are wary when approached, but have by now become somewhat used to curious reporters stepping timidly into their midst to pepper them with questions. They will talk, but not much — and no last names.

“I’m just standing up for what I believe,” says one tall, youthful Skinhead who identifies himself as Michael. “And I’ll fight for it if l have to.”

“White people in America need to wake up and see what’s happening,” chimes in his shorter, stockier friend Eric. “We got no rights anymore. Niggers march and don’t nobody say nothing. Somebody tries to stand up for white people gotta fight for it.”

They grip their beer bottles and glance around to see if they are getting an audience. They complain in rude and graphic terms about the city’s black leadership, the presidential candidacy of Jesse Jackson, and America’s warming relationship with the Soviet Union.

Bill Carmichael, head of the business association, has observed what he identifies as three groups of Skinheads. One is the itinerants, those who come to Atlanta for concerts and protests. “We get Skinheads from out of town,” he explains. “They come from places like Birmingham and Jacksonville.”

The second group is called the “Old Glory Skinheads,” an older, more ideologically oriented group suspected in two recent assaults and several incidents of vandalism. Police say the group has 35 members — and there is evidence that the group has begun recruiting in North Carolina and other Southeastern states.

Teenagers in Charlotte, North Carolina who have joined the Skinheads say they were recruited by the Old Glory Skinheads. According to The Charlotte Observer, at least one of the new Skinheads carries business cards printed with the address and logo of the Atlanta group.

New Skinhead recruits have even begun travelling to Atlanta for demonstrations. Last January, four Skinhead high school students from South Carolina joined a handful of Klansmen and neo-Nazi demonstrators protesting the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday at the Georgia state capitol. State troopers and city police lined the parade route to protect the supremacists. When fighting broke out, police arrested 40 counter-demonstrators. In all, the city spent more than $250,000 to protect the protestors. Skinheads in Atlanta apparently skipped the confrontation.

The third group of Skinheads, according to Carmichael, is the “Nouveau Skins” — rebellious teenagers who come to the neighborhood on weekends looking for identity and trouble. Their random violence has spread fear throughout the community. Last year, a pair of teenaged Skinheads was arrested for defacing a local Jewish high school with swastikas and other Nazi symbols.

“They are mostly kids,” says a spokeswoman for Charis, the feminist bookstore in Little Five Points. Charis, she adds, is seldom bothered by the Skinheads despite its strong anti-racism, anti-sexism collection and window displays.

So far, then, Little Five Points has failed to find a way to take on the Skinheads. Most local merchants continue to express a “live-and-let live” attitude, preferring to blame much of the trouble on out-of-town youths.

Some communities, however, have taken direct action to deal with the Skinheads. In the integrated town of Westminster, California, for example, residents have responded to Skinhead violence by demanding special investigations by police, organizing a neighborhood watch, and developing an extensive anti-racism education program for area youth.

Indeed, the presence of the Skinheads in Little Five Points seems to underscore how dangerous it is for a community to ignore such a narrow and destructive group. Attempts to assimilate the Skinheads have proved expensive and unfruitful, and sitting mute has done nothing to resolve the trouble. Merchants continue to insist, however, that they have done all they can to discourage the rise in violence. All that is left, they say, is to wait and watch — like Patty Lichter, to bar their shops at night and hope the violence never gets worse than a dirty window.

Tags

Julie Hairston

Julie Hairston is a staff writer for Business Atlanta. (1990)

Julie Hairston is a reporter for Business Atlanta. (1989)