Songs of Men

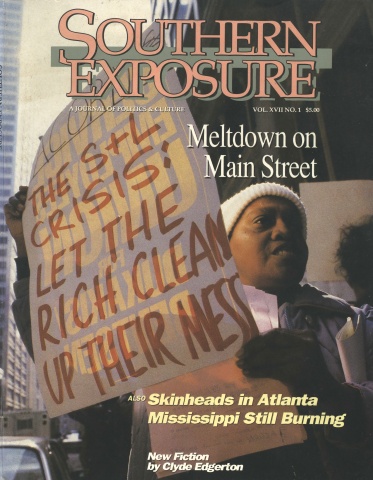

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 1, "Meltdown on Main Street." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

“Most I ever hurt was when I was ten and they went up my pisser. Man, you talk about hurt. They had something that looked like a fountain pen on the end of this long tube-like thing that was hooked to a machine,” says Wesley. He is talking to his roommate, Ben. “Then what they do is touch that thing to the tip of your pisser, and it’s ice cold, and then they stick it in and start it up the passageway which you know ain’t exactly the Holland Tunnel.”

Ben crosses his legs — tight, like a woman in a dress — takes his toothpick out of his mouth.

Ben is black, Wesley is white. Wesley is sitting on his bed, his back against a pillow which is against the headboard, and Ben sits by the window in a cane-bottomed chair, now leaning back, watching this white boy talk. This white boy talks a lot, thinks Ben. But at least he don’t look at you funny, snoop around. He leaves your stuff alone, it seem like.

“I tell you, man,” said Wesley, “it hurt like a lighted match, one of them wood kind, was stuck up there. That’s how bad it hurt.”

Ben covers his crotch with his hand. “Damn.” He looks out across the empty lot beside the halfway house where they stay. “Shit, man.”

“And you know what? Listen to this. You know what they give me for pain?”

Ben looks back. “What? — ‘the pain reliever that works best, Bufferin’?” Ben smiles with half his mouth. He’s thinking about when he hurt most. Easy.

“They gave me a towel — to chew on,” says Wesley. “They had me chew on a white towel. There was a nurse standing right there beside me and when they get ready to do it she hands me this white towel and says, ‘Here, chew on this.’ It was something, man. I ain’t never had nothing hurt like that. I tell you.” Wesley is twenty-four, thin, blond. “What’s the most you ever hurt?” he asks. Wesley decides that Ben hasn’t noticed that he took two quarters off Ben’s bed about twenty minutes ago. He’ll put them back in the next few days — or something.

“Most I ever hurt,” says Ben, “was when I sprained my ankle and got it put in this cast before it started swelling. Next day it started swelling and I had that cast on there and it didn’t have nowhere to swell to.”

“Damn.”

“I even got shot in the back one time and it didn’t hurt like that ankle hurt.”

“Shot in the back?”

“This guy side-swiped my car and kept going and I chased him down. I had this chick with me. I got out and opened the door. He turned sideways, holding onto the steering wheel and kicked me. We got in a fight. His car was running, you know. He kicks me outen the car and then tries to run over me. I start running and finally he gets me pinned in this doorway to this building — we were downtown Burlington about 2 a.m. — and he starts ramming the building trying to get at me, but I’m back up in there where he can’t. Then he leaves and before I can get back to my car he pulls up beside it — down the street in this parking lot. I start running, because the chick’s still in my car, you know. When I’m almost there he opens his car door, and he’s got a pistol. He aims it at me and I keep running at him because I couldn’t believe that this was like real. He shoots and the bullet goes between my legs through my pants, man. I turn around and start dodging left and right like they do on TV and he shoots twice more.

The second one gets me down low in the back. Felt like somebody kicked me. I didn’t know it then but the bullet came out my stomach and fell in my underwear. I rounded the comer at this building and turned down another street still running and go up on this porch and knocked on the door. I’m feeling the blood down in my shoe. This woman comes to the door and I tell her what’s wrong and ast her to call the amalance. She goes and comes back with a mop handle and starts hitting me with it. No shit, man. So I leave there and I see the damn car cross a street down a little ways. The man with the gun. The guy is cruising for me, right? Well, I’m starting to lose it. I feel like I got to lay down somewhere. So I’m in this back yard where there’s a light. I knock on the door and two guys come and I tell them what happened and then I lay down on their porch beside this little steak grill. They called the cops, and the last I remember is laying there on that porch, and blood swooshing out of my shoe, and the lights from the cop car swirling all over the place. I felt bad, but it won’t nothing like that ankle, as far as sheer pain is concerned.”

“Did they catch the guy?”

“Yeah. He got five years.”

“Damn. That don’t seem like much.”

“Hell, no, but I couldn’t get no lawyer and they proved it wadn’t premeditated.”

“But he went somewhere and got a gun, didn’t he?”

“Yeah, this place around the comer where he worked. But they said it was a ‘fit of passion’ or something. Shit. The guy was a bouncer. His brother was in jail for beating up an old lady on the street.”

“Was you in the hospital long?”

“About a week. It made a hole in my pelvis bone but didn’t damage anything else. It was the kind of bullet that didn’t explode. If it had a been, I’d a been dead.”

Wesley and Ben are in BOTA — Back On Track Again, the halfway house sponsored by the federal government and Summerlin College, a small Baptist College in Summerlin, North Carolina, a growing town of 65,000. Ben is in because of an assault conviction, his first. Wesley is in for car theft, second offense. Ben was accepted into BOTA because he is a Negro. Mr. Williamson noticed him — from photographs — his small nose and chin from among several prospects. Mr. Williamson didn’t want a large-nosed Negro at BOTA. He chose Wesley because he knew Wesley had accepted Christ as his Saviour between convictions.

Ben opens the window, pulls a joint from his shirt pocket, puts it in his mouth, lights it, and inhales.

“You going to get caught,” says Wesley. Here is a good man, thinks Wesley, a pretty good guy about to lose his chance at a good deal: BOTA. And a musician. Wesley and Ben are starting a band. Everybody at BOTA must have an “activity” and Williamson had approved a band — “gospel,” Wesley wrote on the activity sheet. Rhythm and blues, actually.

“You get caught and you be in trouble sure enough,” Wesley says. Some people had a hard time learning when to grow up. If it hadn’t been for Mrs. Rigsbee, Wesley is sure he’d still be involved in growing up. Mrs. Rigsbee and Jesus got him grown all the way. Got him mature about love, he figures.

“Anybody knows what it is ain’t gone rat,” says Ben, “and Miss Rodgers, she think it’s pine straw burning.” He takes a drag, holds his breath. “Williamson ain’t around. Too late for him. If I hear some strange footsteps, I fill up my mouth with spit, put it in my mouth and eat it. If I get burn it won’t be no worse than pizza.” Ben flicks ashes in a gold-colored glass ashtray. “I got the rest of it hid so good I can’t even find it myself.

Wesley eyes him a minute, wonders whether he should bring it up. He has roomed with Ben for six weeks. He knows him pretty well. Ben doesn’t mind talking about things. They’ve talked about several man-to-man things. “You ever dated a big woman?”

“Yeah, I dated some big women. I dated some that’s big in parts.”

“I’m talking about big all over.”

“Yeah. My cousin. Skating in the eighth grade. She’d run into the wall and shake the whole place, the whole skating rink. I remember that, man.” Ben pinches the joint between his thumb and forefinger, puts it to his lips, draws, then holding the joint under his nose, sniffs up drifting smoke. “Why? You thinking about taking out that fat chick you been talking to over at the Nutrition House?”

“If I had a car. She’s really good looking in the face. I mean good looking. I met her at church.” Admitting he went to church is a part of Wesley’s changed life, a life with a changed attitude about everything generally — there was the brief lapse when a woman left her white Lincoln Continental with tan leather interior, running with the keys in it, in front of Ken’s Quick Mart. That got Wesley his six months in BOTA. On several other minor occasions Wesley’s understanding of property rights has blurred. “She’s got these blue eyes and black hair,” says Wesley, “and I ain’t ever seen that combination in a woman I could get my hands on — somebody I know. I mean I seen some in the movies. Like Elizabeth Taylor in them old movies.”

Wesley stands and starts emptying change out of his pocket and putting it in the top dresser drawer. He wonders if Ben’s attracted to blue eyes. “You ever dated a white girl?”

“Yeah. One time.” Man, that’s one thing all these white dudes are interested in, thinks Ben. Whether I ever got me any white ass. “Craziest broad I ever knowed.”

“What you think about blue eyes and black hair?” asks Wesley. “It’s okay in the face. But man, she’s fat. She’s real fat.”

“She’s losing though. She’s already lost about twenty pounds. She told me.” Wesley takes off his brown-plaid flannel shirt. He wears a white t-shirt. He sits down on the edge of the bed, looks at Ben. Ben’s eyes are a little glassy. “What I do,” says Wesley, “is just think about her one place at a time. Like her hands look regular, and I figure you get a small enough place, it’s just like any other girl. Know what I mean? But it’s that blue eyes and black hair and white skin I like.”

Ben picks up a two-year-old Sports Illustrated and fans smoke out of the open window. “Turn on that fan over there,” he says.

Wesley reaches over, turns on the fan, stands, and gets his tooth brush and tube of Colgate off the dresser. “I’m gone turn it in. I’m tired.”

“I think I’m going to finish off one more of these,” says Ben, taking another joint from his shirt pocket.

Walking down the hall to the bathroom, Wesley thinks about Phoebe. Phoebe Taylor. He thinks about her often. Wesley feels an inner beauty in her, too. He learned from Mrs. Rigsbee to look at people beneath the surface, to look for what is there. He learned about respecting women. And when she loses that weight, she just might turn out to be the most beautiful woman in the world. The Nutrition House has a good record. People come from all over the United States to that place. Yankees with big cars drive down from New York. Movie stars, except he hasn’t seen any.

Wesley thinks about pushing Phoebe’s love button — the way he used to push Patricia’s, before he learned about how to think about love properly. He thinks there has got to be a way to get Phoebe to go along with having her love button pushed. It shouldn’t be too difficult now that he’s learned about respecting women as human beings. She’ll recognize that and be won over. Then she’ll love having her love button pushed as much as he’ll love doing it. Then he’ll see what happens, naturally.

Saturday night, in the front seat of Phoebe Taylor’s car, Wesley tries to go too far, too fast. She tells him to take her home and not to call her, no matter what.

The following Tuesday afternoon after work, before supper, Wesley is sitting on his bed. A yellow legal pad and pencil lie beside him. He’s playing Ben’s guitar, tuned for bottleneck. Ben has shown him just enough bottleneck guitar for him to get started learning. His plan is to graduate from bass to bottleneck and then trade off — on some band songs — with Ben, who plays both. He writes with the pencil, lays it down on the bed, plays and sings. He has decided to do the proper thing: write a song to Phoebe. He will use his talents in the name of love.

I know you feel mad, I know you’re feeling sad.

There ain’t nothing I can do, but sit right here and get blue too.

I could make it about what I want to happen, thinks Wesley.

I’d be so nice, if you’d call me right now, and talk about the weather

telling me whether you still love me like before — that you do.

Another verse:

Wish you were here, at my front door right now to ring my doorbell,

Ring my blank-blank door bell,

ring my dusty . . . ring my dirty, dusty, — rusty, rusty,

ring my rusty doorbell,

Close enough, let’s see, bell-fail, bell — tail . . . no, I can’t . . . bell — smell, smell, yes.

Close enough for me to smell . . . you.

Ben comes in.

“Ben, listen to this.”

Ben sits down on his bed, listens while Wesley plays and sings, fumbles through the bottleneck positions.

“Here,” says Ben, “give me the guitar. Get your bass.”

Wesley plugs his bass into Ben’s amplifier.

“Do it again,” says Ben. Wesley plays and sings. “Wait a minute,” says Ben. “Try this.”

“What was that?”

“You just go straight to a number three chord, then four. Like this.” Ben plays and hums the tune.

“Sounds good. You ever written any songs?”

“Naw, I just do some instrumental stuff sometimes. Just messing around. You get that thing right and we’ll add it to the list. Sounds pretty good.”

“I’m writing it for Phoebe.”

“Love song, huh?”

“Well, yeah.”

They record it onto a cassette tape in Ben’s tape recorder, Wesley wraps the cassette in a piece of yellow writing paper, tapes it with Scotch tape and writes Phoebe’s name on it.

“I got to go over and put this in her mail box,” says Wesley. “I ain’t supposed to call her or nothing — until she calls me.”

“Why not?”

“We just had this misunderstanding.”

“She told you not to call her or nothing?”

“Call her, see her, anything, until she calls me.”

“She-it. She got you by the balls, man.” Ben stands up, walks over and looks out the window.

“Naw, I wouldn’t say that.”

“She’s telling you what to do.”

“She’s telling me what not to do.”

“Don’t make no difference — it mean the same thing: she got you by the balls. What you do to her, man?”

“I didn’t do nothing. It was what I tried to do.”

“Which was?” Ben stands, looking out the window.

“I tried to push her love button.”

“You tried to push her love button. Ha! “ Ben looks around the room, then back at Wesley. “You mean you tried to fuck her?”

“Naw, man. Look. I been through all that. I mean I done that. I been through that. With other girls. All you got to do is just do it. It’s too easy. But, listen, you know we . . . See, there’s a proper way to go through all this. See, I had a pretty big thing happen to me about four, five years ago.” Wesley knows he’s got to explain it just right.

Ben picks up his guitar, strums a chord. “What? You a Christian? You told me that.”

“I know it, but it’s not like you’re thinking.”

“Hell, that’s all right. All my family Christian. They go to church and everything.”

“I ain’t talking about going to church. I’m talking about it not having anything to do with the church. It has to do with love. The only way I can explain it is to tell you about this woman I was staying with, Mrs. Rigsbee. See, what it comes down to is Jesus and love.”

“I got to go eat, man.”

“I’ll go with you. I want to tell you about this.”

BOTA grants three hours, 7-10 p.m., for dinner on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday nights. They walk outside into dusk, down the street toward The Columbia Grill.

Wesley leaves the tape in the mailbox on the front porch of the Nutrition House, and while they walk, Wesley tells Ben about the first time Mattie Rigsbee came to see him at the Young Men’s Rehabilitation Center, bringing apple pie and pound cake, about her cutting his hair in her kitchen, cooking for him, taking him to church, and finally taking him in. He knows what’s wrong with Ben: he hadn’t learned to respect a woman. Ben is like most guys. They don’t see women as real people. That’s the way he used to be. It used to be that he couldn’t have fallen in love if he’d tried. He might have thought he was in love. That was the shallow kind, back then. Then suddenly there was Jesus in his life, then Phoebe Taylor, and he was in love. The deep kind of love. “You see,” he explains, “there’s this deep kind of love that comes in your life along with Jesus — I mean if it really takes. It changes everything. You find out that women can provide one thing, men another. If you just think about taking from women, you don’t even realize the true value of what they were put on Earth to provide.

“Yeah,” says Ben. “True Value Hardware.”

They walk into The Columbia Grill and get a booth, order two hot dogs each from the waitress. The Columbia is run by Mr. Mike Champion. His main help is his daughter and two brothers. The two brothers move behind the counter in long green aprons. They cook, work the register, and one waits tables during an occasional rush. Mr. Champion himself mostly sits at a table near the cash register, smoking. When someone comes to the cash register, he places his cigarette in the ashtray, collects money, sticks the ticket onto the ice pick, makes change. Occasionally he tells someone to go ahead and find a seat, anywhere. The Columbia Grill has high-backed booths and chalk boards with the daily specials. More permanent menus are written in small removable red and black letters on white boards, one at each end of the room — breakfast combinations, hot dogs, hamburgers, tuna fish.

Wesley is still talking about Mrs. Rigsbee. “We’d have these little practice sessions where she would pretend she was some old person and I’d be me, and then I’d be the old person. She showed me how to shake hands with somebody and look them in the eye and all that. I learned about how a man is supposed to respect a woman. We’d be walking down the street, downtown, and if she was walking next to the street she’d walk closer and closer to me until I finally switched sides.” Wesley demonstrated with his fingers walking on the table. “And see, she connected all this stuff up to Jesus, and that got me interested in all that, you know. And I got to thinking about people different. Women. See, like I never had a family.”

“How’d you get born?”

“I don’t know. I mean I ain’t sure. I just ended up with this uncle because my mama and daddy won’t married for some reason — or something. It was just the orphanage and the YMRC until Mrs. Rigsbee. She got me to thinking about the whole part of people that’s below the surface — the soft spot, the soft area.”

Ben looked at Wesley.

“No, not that. I got to thinking about the whole part of people that’s below the surface. I even got to thinking about communists — I mean, you know, they’re people. They understand the condition of being in love just as well as people in democracies — or they could if they was taught. They got potential.”

“You better watch that shit, man,” says Ben, looking at Wesley as he raises his eyebrows, lowers his head. He has a mustache.

“What I mean,” says Wesley, “is in theory, like.” He picks up the small glass salt shaker and turns it in his hand.

“I don’t know about all that. I don’t know about ‘theory.’ I just know about facts. You can’t count on nothing but bare facts — and there’s no better bare fact than a bare ass.”

“Everything’s got a theory. Anyway, you see what I’m talking about. And that got me to thinking about women and all, and so I figure I don’t want to just up and crawl their ass.”

“You mean you got to do it Christian?”

“Yeah. Well, no, not exactly. That ain’t what I mean. But there is stuff in the Bible which makes it all okay. I was reading some stuff the other day. You know David, the one with the slingshot, killed Goliath?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, he had this illegitimate son, didn’t nobody blink an eye, not even the one writing the Bible, the one getting it all straight from God.”

“I don’t know about that.”

“Oh, yeah.”

“You serious about all this, ain’t you?”

“Well, I think I am, but not in the way they are at church. Sometimes they talk like idiots. They don’t even understand about falling in love — all of that. I can’t imagine anybody there writing a song about falling in love. Much less listening to one. Anybody that dresses that way can’t understand much about falling in love.”

Wesley shakes salt onto his hand, sticks his tongue to it. “Don’t you date anybody?” He looks at the salt shaker. We could use that in the room, he thinks.

“I’m scared to, man. That’s the reason I’m in BOTA. I got charged with rape, convicted of assault. Didn’t you know that?”

“No.”

“Well, hell, you do now.”

The waitress brings the hot dogs, starts to walk away. Ben says, “You think you could put a little more chili on there?”

“Me, too,” says Wesley. “We usually get a lot more than that.”

She picks up the plates.

“Rape?” says Wesley, when the waitress is gone.

“That’s what the charge was. That’s what she said. And she had a hot-shot lawyer and everything. Shee-it.”

“What happened?”

“She called me up, man. To come over to her house and then she started insulting the hell out me.” Ben stares at Wesley. “It was a goddamned fight is what it was — we made love while we was fighting is what happened.”

Wesley tries to visualize the fight. He can’t. “So what happened after that?”

“I got convicted of assault because she was kind of beat up. They dropped the rape because she couldn’t prove it. She called the goddamned police. Can you believe that shit? She called the goddamned police and they came to my apartment and got me, man, and she’d done pressed charges. The only reason the assault conviction held up was because she was beat up a little. The whole problem was she just went kind of crazy, or something.”

“So you don’t date or anything?”

“I don’t date, naw.” Ben stretched his arms, put his hands behind his head. “But like you say, man, there’s all kind of stuff in the Bible.”

“Yeah, I guess so.” Wesley looks at the salt shaker in his hand. “Don’t we need a salt shaker?”

“Maybe I should have written her a song.”

The waitress brought the hotdogs, heavy with chili.

“Yeah, maybe you should have.”

“I don’t know, man. Let me have that salt when you ‘re through.”

Tags

Clyde Edgerton

Clyde Edgerton is the author of Raney, Killer Diller, Walking Across Egypt and The Floatplane Notebooks. (1991)