S&L Q&A

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 1, "Meltdown on Main Street." Find more from that issue here.

What is an S&L?

S&L stands for savings and loan — a type of “housing bank” established in the 1820s to pool money from small depositors and make loans to first-time homebuyers. The original savings and loans were completely non-profit. Citizens who deposited their money owned the S&L, and often drew straws to see who would receive the first mortgage. When every depositor had a home, the S&L was dissolved.

Why couldn’t homebuyers just get a loan from a bank?

Most banks considered it too risky and too unprofitable to give long-term loans to average homebuyers. During the New Deal, the federal government institutionalized the separate functions of banks and S&Ls, also known as thrifts. Unlike banks, savings and loans were required to lend most of their deposits to homebuyers — and in return, they were allowed to offer slightly higher interest rates to attract depositors.

Did this system work?

For the most part, yes. For half a century, small-town thrifts operated smoothly. Combined with federal programs that encouraged veterans and others to buy homes, S&Ls enabled generations of moderate-income families to get home loans. America became a nation of homeowners — and S&Ls were the simple and unseen foundation of the system. Indeed, S &L managers had such an easy job that they jokingly referred to the formula they followed as “3-6-3” — pay depositors three percent, lend at six percent, and tee up on the golf course by three p.m.

Were there any problems?

Certainly. From the beginning, S&Ls — like banks — were fraught with racism. Often run by good-old-boy networks of local white men, thrifts systematically refused to lend money to blacks and other minorities — no matter how good their credit ratings. This institutional discrimination became known as redlining, because S&L officials often drew red lines on maps around inner-city neighborhoods that were off-limits for loans.

Redlining did more than hurt individual borrowers, however. By determining who got loans and where homes were built, bankers helped split American towns and cities into affluent white suburbs and inner-city slums. The sharp divisions created a system of de facto housing segregation that remains to this day.

So why did the system fall apart?

As inflation soared during the 1970s, investors who had their money in long-term investments like bonds began to panic, because their investments were rapidly dropping in value. The Federal Reserve Board — acting against the wishes of Congress and the president — decided to use its control of the money supply to drive up interest rates, hoping to choke off borrowing and throttle inflation. By 1981, interest rates had skyrocketed to over 20 percent.

What effect did rising interest rates have on housing?

A big effect. High interest rates priced average citizens right out of the housing market — they simply couldn’t afford a mortgage. With no incentive to build moderately priced homes, builders turned to glitzy developments and investors began buying and selling existing properties — a game that only the rich could afford to play.

With few affordable new homes being built, many would-be homeowners — especially single mothers and young families — were driven into the rental market. That in turn drove up rents, and higher rents increased homelessness. In short, higher interest rates condemned many to live in substandard housing — and many others to live on the streets, without adequate shelter.

High interest rates also had another effect: they fueled the spread of “financial inventions” like NOW accounts, certificates of deposit, and money market funds that offered depositors a better return on their investments. The response was the equivalent of a run on the bank — depositors took their money out of S&Ls and put it into higher-interest accounts at banks and investment houses.

How did high inflation and interest rates affect S&Ls?

Thrifts were in a double bind. Federal regulations limited the interest rates S&Ls could pay depositors, and also required them to devote most of their loans to home mortgages. They lost deposits by the billions to money market funds, and inflation took a big bite out of the money they made from fixed-rate loans. More than 800 thrifts closed during the 1981-82 recession, and the first round of S&L failures was under way.

How did the industry respond?

Thrifts used their powerful lobbying groups in Washington to push for financial deregulation. Their solution was simple: they wanted to abandon their historic role as the provider of home loans and sink more of their deposits in speculative investments like commercial real estate. In essence, S&Ls wanted permission to gamble with deposits. If they won, they’d pocket the winnings. If they lost, they’d let taxpayers pick up the losses through the Federal Savings & Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), which insures S&L deposits.

What did the federal government do?

Just what the thrifts asked — it deregulated the financial industry, freeing S&Ls to offer higher interest rates to attract more depositors and invest those deposits in commercial deals. At the same time, federal budget cuts hampered S&L examiners who were already stretched thin, making lax supervision even weaker. The industry got what it asked for. Unfortunately, deregulation set the S&Ls up for a fall.

Why was deregulation so disastrous?

Almost overnight, S&Ls started investing in casinos, bowling alleys, windmill farms, luxury shopping malls, fast-food chains, and the junk bonds that pay for leveraged buyouts. Management misconduct and outright criminal activity exploded. The share of S&L lending devoted to home loans fell from 65 percent in 1981 to 39 percent last year.

So the problem was a few greedy managers who took advantage of deregulation?

No — but that’s what the industry wants us to believe. In fact, deregulation created a financial system that actually encouraged corruption and criminal misconduct. Managers were driven to make the highest return on investments no matter how risky the deal, knowing that federal deposit insurance would pick up the costs of the bad loans and speculation. In June 1987, the FBI reported it had 7,350 cases of S&L and bank fraud pending.

So what went wrong with the scam?

The system set up by deregulation was so fragile that any little jolt was bound to bring it down. The first jolt came in Texas, where S&Ls were buying and selling real estate at a frenzied pace. When oil prices fell in the 1980s, the Texas economy plummeted — and S&Ls were stuck with bad loans on miles of vacant office buildings that no one wanted. By 1987, hundreds of Texas thrifts had hit the skids.

If all this is so serious, how come we didn’t hear about it during the presidential campaign?

Good question. Apparently, both parties decided to ignore the issue, since both receive large contributions from the thrift industry and both were responsible for deregulating the industry. As a result, S&Ls were barely discussed until after the election, when dozens of ailing thrifts were sold at bargain prices and George Bush announced the biggest bailout plan in history.

What is the Bush plan?

In February, Bush called on taxpayers, banks, and S&Ls to pay an estimated $126 billion over 10 years to bail out collapsed thrifts. The money includes $40 billion already pledged in government-assisted takeovers, $50 billion in new bonds, plus billions in interest payments on those bonds. The money would allow the government to close about 500 insolvent S&Ls. Bush also proposed requiring S&Ls to have bigger cash reserves to cover losses and to pay higher fees to insure deposits.

Who pays under the plan?

Although Bush labeled the plan “the fairest system that the best minds in this administration can come up with,” the proposal would put more than half the bailout burden on average taxpayers. If approved, the plan will cost every household in the country at least $1,000. Much of that money will go to pay billions of dollars of interest on the bonds Bush wants to sell to finance his bailout plan — bonds that will make even more money for investors who have already benefited from financial deregulation.

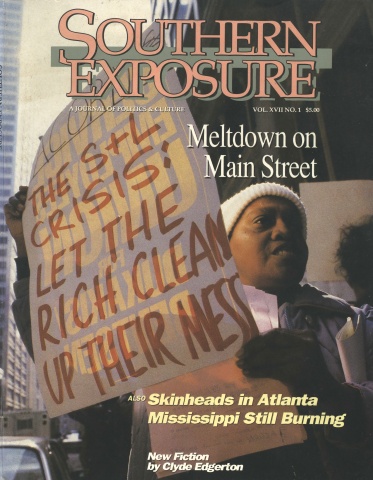

Why should we pay for cleaning up the S&L mess?

We shouldn’t. Ordinary taxpayers did nothing to cause the collapse of the S&Ls, nor did we benefit from the big-time investments that caused the collapse. In fact, most taxpayers are net debtors and have been victimized by the record-high interest rates and instability caused by financial deregulation.

Does the Bush plan address the housing crisis?

No. Not one word of the president’s proposal refers to the national housing crisis — the very dilemma that S&Ls were created to solve.

Will the plan reform the financial industry?

No. The plan ignores the basic problems that torpedoed the thrift industry. It does nothing about the large number of S&Ls that are hiding their insolvency with bookkeeping tricks. It does nothing to get deposit insurance out of the bailout business and restore it to its original purpose of protecting small investors. It does nothing to open financial institutions and their regulators to greater public scrutiny and participation.

So what will we get for our money?

Not much. Bankrupt S&Ls will be closed or sold off. But those that remain open will continue to benefit from a host of public protections — paid for by the average taxpayer. The result is likely to be increased concentration of ownership in the financial service industry, with large financial institutions swallowing up small-town savings and loans.

Is there an alternative?

Yes. The collapse of the savings and loan industry offers a rare chance to restructure the way high finance does business in this country. The Financial Democracy Campaign, a coalition of hundreds of grassroots groups, has made specific recommendations that would restore public priorities to the financial industry and ensure that such a calamity won’t happen again. For more details on the recommendations, see page 19.