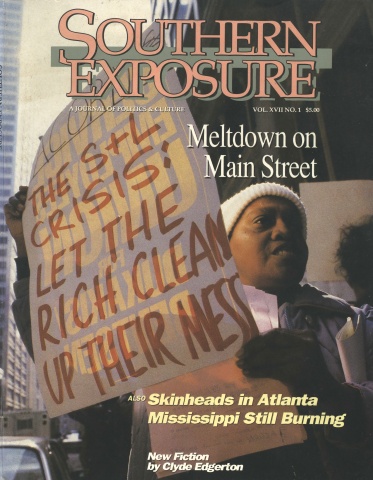

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 1, "Meltdown on Main Street." Find more from that issue here.

Little Rock, Ark. — Foster Strong bought his modest frame home on the west side of town in 1963. He was in the dry cleaning business in those days, a good business, and he didn’t have any trouble getting a $10,000 mortgage from a local savings and loan.

For 25 years, Strong made his $85 monthly payments on time, every time — 300 payments and never missed a one. He grew old with the tree-lined neighborhood, retired, set up an upholstery shop in his garage, and started taking it easy.

Then one day he picked up the newspaper and read that FirstSouth, the savings and loan that held his mortgage, had been shut down by federal regulators. FirstSouth, it seemed, had loaned more than $600 million to top stockholders — enough money to give every family in Little Rock a home loan like Strong’s. With huge losses on its loans, FirstSouth was broke — and federal officials turned Strong’s mortgage over to First Commercial Bank.

“They sent me a letter,” recalls Strong, 72. “They said they had recalculated my mortgage — something about not enough money in escrow, yakity-yakyak. They upped my payment from $85 to $132 a month. I thought I had a fixed rate, but I can understand what happened — somebody got greedy.”

For retirees like Strong who live on fixed incomes, an extra $564 a year in house payments is a lot of money. “It’s a struggle,” he says. “I’m making the payments, but it’s a struggle.”

Peeling Paint, Broken Windows

Few states have been as hard hit by the collapse of the savings and loan industry as Arkansas. A third of all Arkansas thrifts have folded since 1986, swallowing half of the $8 billion deposited in S&Ls statewide. That’s more money than the state government spends in an entire year — enough to give every man, woman, and child in Arkansas $1,750 in a state where the average annual income is only $11,343 per person.

The staggering loss has sent shock waves through city neighborhoods and small towns across the state. Hundreds of houses owned by insolvent S&Ls have been seized by the federal government and boarded up. Homes that were once the pride of the community now stand empty, their paint peeling, their windows broken. And with billions of dollars of S&L mortgage money gone for good, families eager to buy homes are finding it tougher than ever to get a loan.

“Arkansas is a comparatively poor state, so anything negative that happens here has a greater impact on poor people than it would in a more prosperous state,” says Arthur Cross, a disabled nursing assistant who is concerned about the thrift crisis. “Many of our communities are very small and rural. In those areas, citizens often have only one financial institution in the whole town. When it becomes insolvent, the effects can be devastating.”

The direct and immediate effect of the financial crisis has spurred residents like Cross and Foster Strong to take direct action. In the past six months, angry citizens in Arkansas have demonstrated at banks and savings and loans, confronted federal regulators in Texas and Arkansas, and taken the government to court to force it to open the books when it auctions off S&Ls.

Now, some residents say they are fed up with the growing number of abandoned houses going to waste in the city. Led by the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN), a grassroots group based in Little Rock, residents are demanding that the federal government turn over all foreclosed houses to the city or the local housing authority so they can be used by people who need them.

If their demands are not met soon, residents say, they are prepared to take over the houses and fix them up themselves — with or without the permission of the government.

“I think we’re going to see increased activity around those houses,” says Zach Polett, regional director of ACORN. “People are saying that they can’t afford to wait for someone else to fix them up — we have to fix them up ourselves before they destroy our neighborhoods. People are just going to start bringing out the paint scrapers and paint brushes and fixing up those houses and moving families in.”

“Makes Me Angry”

It doesn’t take a financial wizard to see what has driven residents in Arkansas cities like Little Rock and Pine Bluff to talk about seizing abandoned federal property. Driving along the streets of Little Rock, even the most casual visitor cannot fail to miss the signs of urban decay. As in many Southern cities, the neighborhoods are a study in contrast. Wide-porched homes stand next to tiny shacks and vacant houses. Here, crossing from a rich neighborhood to a poor neighborhood can be as simple as crossing the street.

Lillian Minton lives on West 13th Street, a bit south of downtown, in a neighborhood that exemplifies the stark contrasts. Three-story Victorian homes — immaculately restored with cut-glass doors, mahogany floors, and gleaming brass appointments — stand alongside shells of gutted and roofless buildings. The neighborhood is home to the governor’s mansion, as well as the comfortable suburban house seen in the opening credits of the TV sitcom Designing Women.

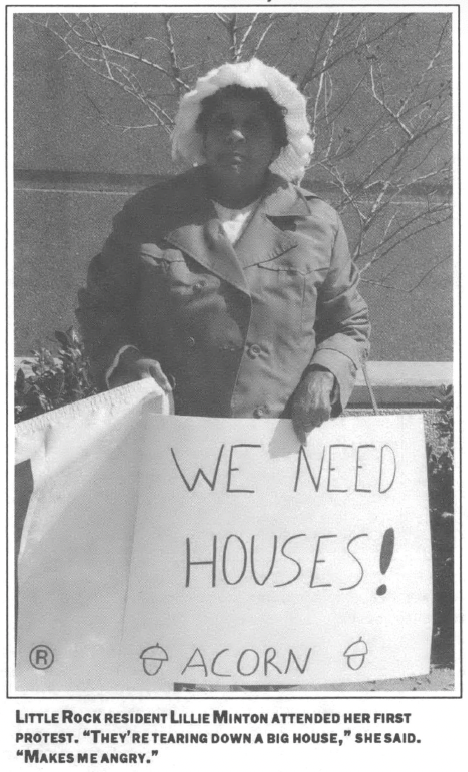

On March 10, Minton joined dozens of other ACORN members who demonstrated outside the downtown headquarters of the Federal Savings & Loan Insurance Corporation to demand that foreclosed homes be turned over to the community. It was the first protest Minton ever attended. She carried a sign that read: “We need houses! ”

“Next door to me they’re tearing down a big house,” Minton explained. “Makes me angry. That house could be lived in with a little work. But drifters are sleeping in it, and somebody’s been tearing off the siding. They’ve even broken into my house three or four times. And it’s all because of what’s happening in my neighborhood.”

Such stories are not uncommon. Although federal officials refuse to disclose how many houses they have foreclosed, Foster Strong has counted eight abandoned homes in his neighborhood — and he knows that at least two of them belong to the government.

“I know something could be done other than letting the houses sit here and rot, devaluing the neighborhood property,” Strong says. “I feel like, if the government is going to take our tax money and bail out the S&Ls, then why can’t somebody use those houses and pay a smaller amount of money over a longer period of years? The point is, they are just going to hand our money to the S&Ls. The rich get a little more money to put in their pockets, and the houses will just fall down. What I want to know is, what’s going to happen to all these people living out in the streets? What’s the government going to do for them?”

Fellow ACORN member Arthur Cross agrees. “If a house is sitting empty, the government is ultimately responsible for it. We feel that in a sense the savings and loan crisis and the housing shortage — the homeless people on the street — go hand in hand. If these houses were used instead of just sitting vacant, it would be to everybody’s benefit.”

The Anger Spreads

Arkansas citizens angered by the savings and loan crisis haven’t been content to simply voice their outrage at the local level. In February, ACORN members drove 300 miles to Dallas to confront regulators at the Federal Home Loan Bank Board who were using secret bids to auction off six failing thrifts in Arkansas and Texas. Determined not to allow the troubled S&L industry to take any more action behind closed doors, the Arkansas group demanded that all bailout deals be open to public scrutiny. When officials refused to disclose any details of their dealings, the group filed a lawsuit under the Freedom of Information Act.

Then on March 2 — less than a month after George Bush proposed rewarding the S&L industry with the biggest bailout in history — Little Rock residents took their anger directly to Washington. Former ACORN president Elena Hanggi attended a press conference to help kick off the Financial Democracy Campaign, a national coalition of nearly 200 civil rights, labor, church, and community groups calling for comprehensive reform of the financial industry.

“I’m from Little Rock, Arkansas, and we are the pulse of what’s happening in this Financial Democracy Campaign,” Hanggi told reporters. “In Arkansas, S&L has come to stand for squander and liquidate.”

“We’re tired of being taken for granted in the S&L mess,” she continued. “Our frustration grows daily. This is a roar of anger that cannot be silenced and will not be ignored. We did not create this mess. We did not benefit from this mess. And we should not have to pay for this mess.”

The campaign proposed a variety of remedies as alternatives to the Bush bailout plan — and housing needs were at the heart of the recommendations (see “A Blueprint for Financial Reform”). Hanggi and other members of the coalition called on the government to outlaw discriminatory lending practices, turn vacant homes over to those who need them, force firms that buy insolvent thrifts to invest in local communities, and require all financial institutions to commit money to low-and moderate-income housing.

“Any bailout must be linked to returning savings and loans to the business of housing Americans,” said Jesse Jackson, a spokesman for the campaign. ‘There must be some commitment to the original purpose of savings and loans — they must be in the business of making housing affordable.”

Jackson said the burden of any bailout plan should fall on wealthy investors who have profited from financial deregulation — not on citizens who have suffered from it.

“Let those who had the party pay for the party,” Jackson said. “Over the past decade, the after-tax income of the majority of Americans has been stagnant or worse. The after-tax income of the top five percent increased by more than a third; that of the top one percent by 75 percent They benefited from high interest rates and massive tax breaks. Low-and moderate-income people did not cause this crisis; they were damaged by it — as mortgages grew more costly and less secure. It does not make sense that those who never were invited to the party should be asked to pay to clean up the mess.”

Regnat Populus

Sitting in his home in Little Rock, looking through the book of higher mortgage-payment slips the bank sent him, Foster Strong echoes that thought.

“They are bailing out the S&Ls with our tax money,” Strong says. “Nobody can tell me that with the deregulation that has gone on in this country in the past few years, that 90 percent of what’s happening with the S&Ls is not either carelessness or greed. There is a lot of money that wound up in people’s pockets. And the way it’s set up, they will never have to account for it.”

“You can’t tell me that all of these guys are going down the drain through bad investments,” he scoffs, rejecting the standard explanation for the collapse of the S&L industry. “What do you mean, bad investments? With deregulation, I can loan my brother $10 million, and I don’t have to account for it and he doesn’t have to pay it off. Is that a bad investment?”

Polls show that most people agree with Strong. According to a recent survey by Lou Harris, 60 percent of all Americans oppose the Bush plan to make average taxpayers shoulder the burden of the S&L bailout.

If the Financial Democracy Campaign succeeds at channeling such widespread popular frustration into effective grassroots action, organizers say, it could fundamentally change the way the nation’s financial industry does business. Groups in the coalition say they plan to conduct community hearings, flood congressional offices with postcards, testify before Congress, file lawsuits to demand full disclosure, and meet with S&L officials and federal regulators across the country.

In many ways, the national campaign mirrors community action already underway in Arkansas. But some residents in Little Rock have taken things a step further — they have decided to show big-time developers that low-cost housing is a smart investment. Working with ACORN, community volunteers have formed their own non-profit development corporation to renovate existing homes for low-income families. The group has already housed six families and is currently working to fix up two more houses.

“We realized that part of the housing solution has to be us doing it ourselves,” says Zach Polett, ACORN regional director. “We hope that by establishing this model and a good track record, it will encourage investment by the financial community.”

The renovation efforts in Little Rock serve as a vivid reminder that the effects of the savings and loan crisis extend far beyond the bank board rooms and glittering office towers. Beneath the current financial crisis lies the national housing crisis, the widespread shortage of decent and affordable homes, the growing number of homeless people in the big cities and small towns of states like Arkansas.

The renovation efforts also serve as a reminder of the power and potential of community organizing. In a state that boasts the lofty motto Regnat Populus — “The people rule” — some citizens are beginning to suggest that democracy should extend to the all-too-political world of high finance.

“We don’t have a mass movement sweeping across Arkansas like a prairie fire,” Polett says, “but what has happened here shows that organizing works. If people are given the information they need, they are really ready to move.”

Foster Strong was one of those who was ready to move. Although it has been only a few months since he started organizing neighbors to take action, he is convinced that the answer to the crisis in the savings and loan industry will come from Southern communities like Little Rock and Pine Bluff.

“There are a lot of people who think, what can I do?” Strong says. “I just came from a city council meeting tonight, and the feeling of a lot of people who were there was, I am wasting my time — I don’t have a voice in what goes on. Well, one person doesn’t have a voice. But together, a lot of people do.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.