New Blood for the Old Order

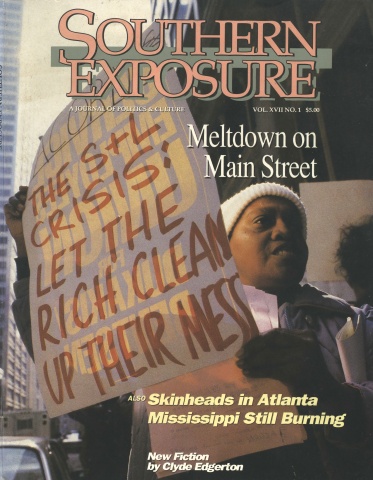

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 1, "Meltdown on Main Street." Find more from that issue here.

When former Ku Klux Klansman David Duke won election as a Louisiana state representative in February, he was quick to trumpet his victory as a sign that voters are showing renewed interest in white supremacy.

“I think you’re going to find candidates across the state and across the country begin to talk about the issues I’m raising,” Duke boasted. “I think this is the beginning of a change in this country.”

Duke’s success in electoral politics marks a culmination of a decade of conscious strategy by white supremacists. Faced with dwindling membership throughout the 1980s, hate groups like the Klan have been looking for a way to bring their genuinely fascist politics into the mainstream — and Duke has provided the first major victory. Elected office lends legitimacy to his neo-Nazi beliefs and gives him a national platform from which to speak, and he is taking advantage of it every chance he gets.

In many ways, Duke represents the legacy of eight years of the ultra-conservative political movement spearheaded by Ronald Reagan. Reagan came to power in a conscious effort to place a far-right political agenda at the center of American politics — an agenda that displays nothing but contempt for the poor and disadvantaged — and by and large he succeeded. In doing so, he created an opening for white supremacists like Duke, who are now working to maneuver an even more extremist agenda to the center of the political spectrum.

This was not the first electoral success for Duke. Before he ran for state legislature, he had already won 20,000 votes in Louisiana as a Democrat in the presidential primary last year, and 18,000 votes as an Independent in the general election.

In essence, Duke has sent a signal to white supremacist candidates that they don’t always have to hide behind the thinly veiled euphemisms used in mainstream politics — it is sometimes possible to win an election by being openly racist.

Although many are portraying Duke as an isolated Southern racist, his victory also serves as a reminder that the American mainstream is not immune from outright fascism. After all, Klan candidates have won elections in this country before — most notably in the 1920s — and they have won them in the North as well as the South.

“Duke is not an isolated phenomenon,” says Leonard Zeskind, research director for the Atlanta-based Center for Democratic Renewal, a non-profit group that monitors white supremacist activities. “This thing could happen anywhere. It could happen in Yonkers.”

Above-ground electoral politics is just one of the current white supremacist strategies. Another is underground paramilitary training and organized violence. Klan and neo-Nazi groups have spent much of the last decade organizing secret armies and carrying out guerrilla raids across the country. Now they are increasingly turning to the street violence of the Skinheads, small groups of teenagers who operate as neo-Nazi youth gangs, complete with high boots and swastika tattoos.

“For the first time, a nationwide racist movement is being initiated by teenagers who are not confined to any single geographic region or connected by a national network, but whose gangs sprang up spontaneously in cities throughout the country,” concludes the annual report of Klanwatch, a non-profit group that monitors white supremacist activities for the Southern Poverty Law Center. “Not since the Ku Klux Klan of the 1950s has a white supremacist group been so obsessed with violence, and so reckless in its disregard for the law.”

As the articles in this special section of Southern Exposure demonstrate, Klan leaders themselves have made no secret of their desire to unleash Skinhead violence on blacks, Jews, and gays. “If there’s a future for the right wing, Skinheads will be the first racial wave,” says Klansman Robert Miles. “They’re what the Nazi storm troopers were in the early ’20s: disenfranchised working-class youth who were given uniforms, a bed in the barracks, three meals a day, and a purpose.”

The articles in this section provide a clear picture of how white supremacists have changed their strategy in the nine years since we examined them in our full-length issue, The Mark of the Beast (SE Vol. VIII, No. 2). The stories take us from West Virginia, where neo-Nazi publisher William Pierce has set up a rural commune to indoctrinate children; to North Carolina, where hate groups followed a blueprint by Pierce for a violent takeover of the government; and finally to Atlanta, where the Skinheads began to surface just as older Klan and neo-Nazi leaders were being prosecuted for their crimes.

Despite the shifting face of the Klan and other hate groups, some things have not changed since we published The Mark of the Beast in 1980. As we wrote then, “The Klan is only the mark of a larger beast — institutional racism and other forms of corporate exploitation. If the Klan is allowed to spread its venom unopposed, it will grow to proportions which threaten unions, community organizations, and decent people everywhere.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.