This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 1, "Meltdown on Main Street." Find more from that issue here.

Lena Tyler was just a child when her mother began fighting to improve Mississippi schools in the 1950s and ‘60s.

“She told us that many doors would not be open to us because of our color,” Tyler remembers. “I didn’t understand what that meant then. When we marched — the Ralph Brown marches and the Martin Luther King marches — we marched because she marched. It wasn’t until much later that I knew what she meant.”

Today Tyler, a state welfare worker, knows exactly what her mother meant. As a leader of the Mississippi Association of State Employees — known as MASE — Tyler is at the heart of some of the most important labor organizing to sweep the state in years. She and hundreds of other state employees are struggling to build what they call “a civil rights movement for workers” — and like those before them, they say, they intend to fight until they win.

“My mother said that this struggle is like a relay race — you run as far as you can, and then you pass the stick on,” Tyler says. “After she ran as far as she could, she passed it on to the next generation, which was me. And I haven’t regretted it.”

Working Poor

State employees like Tyler have good reason to organize. With 38,000 people on the government payroll, the state is the largest employer in Mississippi — and it is also one of the worst. An estimated one-third of all state employees live below the poverty line, and many make less than $14,000 a year. Roughly half are single mothers, most of whom have to work second jobs simply to make ends meet.

As a result, thousands of state employees have been forced to apply for welfare — and it is not uncommon for professional welfare workers with college degrees to find themselves sitting on both sides of the table. “It’s discouraging to see more and more state employees come in for food stamps, Medicaid, and Aid for Families with Dependent Children,” says Betty Miller, a 16-year veteran with the Hinds County welfare department.

Yet perhaps even more important than low wages, employees say, are the miserable working conditions typical of state jobs. Many workers are subjected to dangerous and unsafe conditions, and say they want their employer to treat them with dignity and respect. “I’m over half a hundred,” says one University of Mississippi employee, “but they still call me boy.”

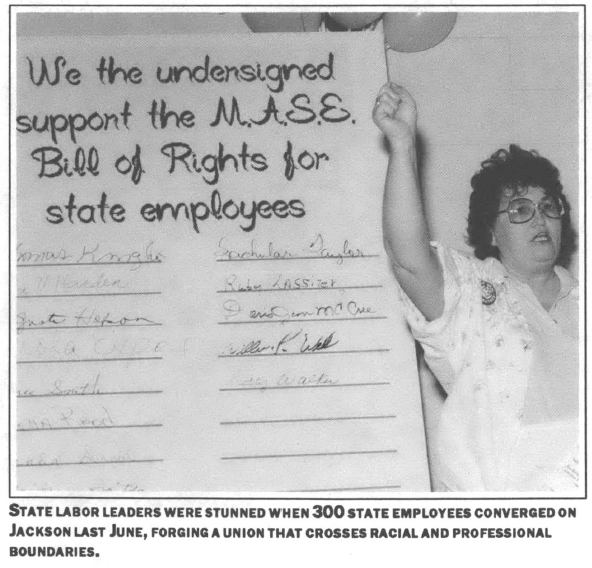

It was out of such conditions that MASE was born. Although it is still in its infancy, the fledgling union has already made great strides. Last June — only eight months after workers started building the union — 300 state employees converged on Jackson to officially found MASE and ratify a “Bill of Rights” for state workers (see sidebar). The meeting united employees across the state, forging an organization that crosses professional and racial boundaries.

State labor leaders were stunned. “I had never seen anything like it,” said Neal Fowler, president of the state AFL-CIO. “It was sort of a feeling of surprise to see that many state employees. The feeling was one of elation that this many people would come together, especially considering how many state agencies they came from. It’s just one of those things you get wrapped up in. You just want to go with the flow.”

School Lessons

Although the rapid rise of MASE took the state by surprise, it was actually the product of more than a year of hard work and careful organizing. It started in 1987, when a handful of frustrated state workers and a few committed organizers began talking about how to create a unified voice for state employees that would be heard — and respected — in the halls of the state capitol.

Two developments in Mississippi spurred state employees to take action. The first was a series of dramatic political moves by school teachers. In 1985, for the first time in the history of the state, teachers staged a walkout to demand decent pay. The strike eventually spread to include more than 9,000 strikers — more than a third of all Mississippi teachers — and 466,000 school children. Teachers later took their anger to the ballot box, helping to elect a slate of progressive legislators who gave teachers a pay raise early this year.

The teacher’s new-found political activism made a deep impression on state employees. “The teachers taught us last year, if we don’t stand together, we won’t get anywhere,” says welfare worker Betty Miller.

The second development that galvanized state employees was the election of Ray Mabus as governor in 1987. As state auditor, Mabus had put dozens of crooked county supervisors behind bars, gaining him a reputation as a reformer intent on rooting out corruption.

During the campaign, Mabus vowed to raise teacher salaries to the Southeastern average, reform the county government system, slash the number of state agencies, and make each agency more accountable to the governor. Voters, rankled by the national image of their state as an American backwater, responded to his campaign promise that “Mississippi will never again be last.”

The public responded, and so did state employees. Even before they had so much as an organizing committee, a handful of workers assembled on the steps of the state capitol to endorse Mabus and condemn the State Employee Association of Mississippi (SEAM), a group which claims to represent state workers. SEAM had endorsed Jack Reed, the Republican candidate for governor known for paying workers in his garment factories substandard wages.

“SEAM has never represented the interests of a majority of state workers, it has represented the interest of managers and administrators,” said Jesse Aired, a psychiatric aide at the Mississippi State Hospital and one of the founders of MASE. “No group representing average state employees would have endorsed a sweatshop boss for governor.”

Around the Clock

By the time Mabus won election, organizers like Aired were working around-the-clock to build MASE into a powerful voice for state employees. Aired would work a midnight-to-eight a.m. shift at the state hospital at Whitfield and then drive four hours to organize employees on the Oxford campus of the University of Mississippi, returning to Whitfield just in time to start his next shift.

In many ways, Whitfield was one of the most important institutions in the state system to begin organizing. The third largest facility in Mississippi, its horrible working conditions give it a reputation as one of the worst places in the state to work. An overwhelming proportion of the employees are black women, stuck in dead-end jobs that pay as little as $7,000 a year.

Jay Arena, another Whitfield employee who was working to organize MASE, recalled how many of his co-workers had to pay Whitfield part of their wages to drive them to and from work along circuitous routes that added hours to their travel time.

“I remember one co-worker, she was making $620 a month, living with her two kids in a shotgun house,” Arena said. “On top of that, she had to pay Whitfield $50 a month for transportation to work and back, which added two hours to her work day.”

Although Whitfield employees work in dozens of buildings scattered across the hospital compound and have almost no contact with each other, Arena and Aired were soon able to collect hundreds of names on a petition to “support the formation of an organization to stand up for our rights in the workplace and the legislature.”

While Aired and Arena were talking to state employees at Whitfield, other workers were focusing on the Oakley Training School, a juvenile detention center where runaways and first-time shoplifters are locked up with convicted murderers. Employees accused the administration of deliberately creating dangerous working conditions and making no attempt to rehabilitate youth offenders. When MASE began organizing at Oakley, more than 80 percent of the workforce signed a petition calling for the resignation of the director.

The initial victories — and the endorsement of Mabus — started to attract media attention to MASE and increase its public exposure. Employees from across the state began calling the group and asking for help, and the small staff of volunteer organizers found themselves stretched thin.

Most of the organizers were young activists who were working full-time jobs to support their full-time organizing. One worked in a library, another at a radio station; one even delivered pizzas to pay the bills. In their off hours, they fielded phone calls, organized press conferences, and criss-crossed the state holding house meetings with state employees to discuss the new union.

“We were just a ragtag organization that had accidentally stumbled across a tremendous need in Mississippi at a time when there was a lot of political change in the state,” recalls one organizer. “We were trying to build the union piece by piece, but we knew we needed the support of an established union if we were going to build a statewide organization.”

Fortunately for MASE, the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU) took an interest in its efforts early last year. While other unions shied away from the mammoth task MASE had undertaken, ACTWU agreed to commit organizing expertise and financial support. Working with Jonathan Lange, Southern organizing director for ACTWU, state employees decided to organize MASE as a statewide political organization that could put pressure on the legislature to increase pay and improve working conditions. Employees began planning the June meeting, hoping to get 100 leaders to attend.

People vs. Money

Instead, more than 300 state employees showed up, and MASE was officially born. The atmosphere at the meeting was euphoric, as workers began to realize there was a groundswell of support for building a statewide union of state employees.

“There are two kinds of power,” Lange told employees at the meeting, “the power of money, and the power of people. They may have the power of money, but we have the power of people.”

By September, MASE had pulled off an even larger meeting. This time, nearly 800 workers descended on Jackson State University for the union’s first statewide convention.

As the meeting wore on, worker after worker approached the microphone to “testify” about the low pay and daily struggles on their jobs. Hewie Gipson told of working for the Lamar County welfare department for 18 years, only to learn that his counterparts in New Jersey get a starting salary of$16,000.

“Ladies and gentlemen, I’m just now reaching that $16,000 mark after 18 years,” Gipson said. “I have a solution to this. It’s called M-A-S-E.”

As MASE grew, its success and style prompted some to compare it to a full-fledged movement. Not even a year old, it was already drawing hundreds of workers to statewide meetings, grabbing headlines in newspapers, and translating the frustrations of workers all over the state into a cohesive political campaign.

Although most MASE supporters stop short of describing it as the heir to the civil rights movement, it has struck a deep chord with state employees who remember the early days of struggle in Mississippi. In country churches and rural homes across the state, MASE leaders have heard years of pent-up frustrations from workers who still vividly recall the dreams and victories of the Freedom Movement. Many lived through the assassination of Medgar Evers and other civil rights workers, the marches, sit-ins, and demonstrations.

“It is the mission of every labor union to address civil rights in the workplace,” says Charlie Horhn, president of the Mississippi A. Philip Randolph Institute. Indeed, bringing civil rights into the workplace may prove to be the strongest link MASE is forging. State employees point out that there never really was a “civil rights movement for workers” in Mississippi, and many are eager to pick up where the activists of the 1960s left off.

While the civil rights movement made great strides in overcoming racism in public life, Horhn and others point out that racism remains a useful tool for factory owners seeking to divide white and black workers. According to Charles Tisdale, publisher of the Jackson Advocate, “Factory owners have conceded certain privileges to white workers that are not conceded to black workers,” splitting the workforce and undercutting the racial solidarity unions need to succeed.

The same forces are at work in the state civil service in Mississippi. Unlike federal employment, a state job is no guarantee to upward mobility for blacks or whites. Many state employees work for years in dead-end jobs that pay poverty wages and offer virtually no chance for advancement.

Breaking Barriers

From its inception, MASE has sought to break down racial barriers and bring black and white workers together — a goal that has eluded many unions in Mississippi in recent years. And from the look of its two first statewide meetings, it may well succeed. A sizable number of white state employees showed up at both meetings, and dozens of white and black textile workers who belong to ACTWU came to the meetings together to show the newest members of their union that solidarity across race lines was a goal worth striving for.

White employees like Betty Miller say they recognize the need for MASE to build on the legacy of the civil rights movement.

“It’s good that as employees, black and white, we’re trying to band together to make it better for the people of Mississippi. The union’s stronger to have black and white together,” she said. “Things have changed in Mississippi — we would not have had this even 10 years ago. We have a lot to learn from each other. We’ve grown closer together. Not as races, but as individuals, we are learning to stand up for each other.”

The way MASE crosses job classification, race, and gender has set it apart from traditional organizing drives. Organizers say the typical union model used in the private sector — signing up workers on membership cards, demanding recognition from the employer, and holding shop-floor actions — simply wouldn’t work for a group as large and diverse as the 38,000 state employees. Instead, MASE has opted for a low-key political strategy that uses a broad Bill of Rights to bring blacks and whites, men and women, janitors and professionals together around a common agenda that directly addresses their self interest.

As one MASE leader told a group of disability specialists, some of the highest-paid state employees: “We’re not talking about a union just for you up on the eighth floor. We’re talking about the whole building, right on down to the man out there mowing the grass.”

Despite its early successes, few question that MASE is in for a long, tough fight. Like all labor unions, it must find a way to translate its energy and large meetings into strong local organizations that can fight it out on the shop floor. When it does, many observers say, it may find that the “new Mississippi” heralded by Governor Mabus will turn out to be a poor defense against the organized resistance of mid-level state managers.

“A whole lot of people just hoped MASE would help without too much controversy,” says former state Senator Henry Kirksey, a civil rights activist and long-time labor supporter. “The thought of management was, it won’t succeed. As long as it’s not hurting, there’s no sense putting on the boxing gloves. Once MASE begins to organize, then you’ll see management coming out. It sounds progressive not to hammer away at unions, and they want to sound progressive.”

Such concerns underscore the difficulty MASE faces as a union of workers who have the entire state government as a boss. Mississippi has no collective bargaining law for state employees, making it difficult for them to negotiate a contract.

Without a contract, MASE will have to find creative ways to collect dues from members and represent workers who are mistreated on the job. The state personnel board currently allows workers who are disciplined or fired to appeal, but the union has not always been permitted to represent workers in grievance hearings.

For now, though, the major task facing MASE is to spread the word and bring state employees together for the first time. State Senator Alice Harden, who signed the MASE Bill of Rights, says she believes the union can accomplish what no other organizing drive has accomplished in Mississippi.

“The sky’s the limit,” Harden says. “MASE is to be commended for its organizing efforts. The state convention was an excellent effort — now they have to move on from there. They have to convince people that it can work.”

Garry Ferraris, international vice-president and Southern director of ACTWU, told workers at the statewide convention last September that it can work. He said the union is committed to putting its best resources into the effort, and urged workers to continue organizing until their Bill of Rights becomes a reality for all state employees.

“I believe if we’re patient enough and we’re disciplined enough,” Ferraris said, “the governor of the state of Mississippi will come before you and proclaim MASE’s agenda is Mississippi’s future.”

Tags

Ann Long

Ann Long, a former staff writer for The People’s Voice, worked on the MASE campaign and other Mississippi labor projects. This story was financed in part by the Southern Labor Fund of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1988)