This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 1, "Meltdown on Main Street." Find more from that issue here.

When Houston developer Roy Dailey bought First Savings of East Texas for $ 1.25 million, he ran the small savings and loan like his personal fiefdom. In those days, Texas real estate was hot, so Dailey dumped the deposits of First Savings into shady land deals all over town. Within two years assets had nearly quadrupled, from $29.2 million to $118 million.

Before long, however, Dailey’s questionable lending style led to confrontations with federal regulators, who stripped him of control twice in 1985. Dailey was furious. In February 1986 he marched into First Savings, flanked by an armed force of six off-duty police officers. The banker and his hired guns held the S&L hostage for several hours before finally surrendering control to authorities. A year later, the FBI began investigating Dailey for bank fraud.

Guns, money, greed — the tale has all the elements of a bestselling novel. In fact, such stories have been all-too-common in recent years, as white-collar criminals like Dailey literally looted the deposits of hundreds of hometown savings and loans across the country. In all, they ripped off $100 billion, bankrupting more than a thousand S&Ls. By the end of 1987, there were 7,350 cases of bank fraud awaiting FBI investigation.

As a result, the federal agency that insures S&L deposits is now also bankrupt — and President Bush has proposed the biggest bailout in history so it can close more insolvent thrifts and pay off depositors. The size of the bailout is almost too enormous to comprehend. Some estimates put the cost as high as $335 billion — bigger than the Marshall Plan to rebuild post-war Europe and the bailouts of New York City, Lockheed, Chrysler, Penn Central, and Continental Illinois combined.

Such numbers underscore how the collapse of the financial industry affects each of us directly. If approved, the Bush plan would take at least $1,000 from every taxpayer in the country and use most of the money to refund the accounts of the large investors who helped cause the crisis in the first place by teaming up with the likes of Roy Dailey. In essence, Bush wants to tax the poor to subsidize the rich. At current tax rates, the plan would cost Southern taxpayers $89.7 billion — enough money to run the entire government of West Virginia until the year 2014.

The numbers are numbing, the controversy shrouded in technical detail and boring regulations. It can all seem so distant, so removed from our daily lives. But in truth, the crisis in the savings and loan industry hits dangerously close to home.

Above all, the current financial crisis is about housing — and homelessness. Savings and loans were actually created to make affordable home loans to first-time homebuyers, and for decades they served as safe havens for small investors. Most Americans put their money in their homes, and S&Ls earned the nickname “thrifts” for their dedication to thriftiness and home ownership.

All that changed in the 1970s — beginning in Sunbelt states like Texas and Florida. As Curtis Lang reports in his article on page 20, the region’s real estate market was booming, and Southern savings and loans were eager to sink their deposits into speculative land deals. Squeezed by inflation and high interest rates, they pressured their states to deregulate the industry — to let them invest more money into commercial real estate — and they succeeded. The federal government followed suit in 1982, giving S&Ls the go-ahead to gamble deposits on risky land deals while still pledging to pay off depositors if the bets fell through.

The result, it turns out, was like releasing a house cat in the jungle. The once-tame thrifts were suddenly unleashed to make wild real estate investments — and they got eaten alive. They poured billions of dollars into risky loans for new office towers and fast food restaurants and condos. Before long, the market was overbuilt, with more buildings than occupants. Real estate values plunged, and S&Ls were stuck with billions of dollars in defaulted loans.

The savings and loan crisis soon spread from Texas to the rest of the region. The South is home to only a third of all S&Ls, but half of the insolvent thrifts are located in the region — including 39 of the 50 most deeply in debt. Four Southern states outrun the national average for the percentage of their S&L assets that have been repossessed — Texas, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

Even thrifts in Southern states like North Carolina, considered to have a thriving economy and a stable S&L industry, are exhibiting the symptoms that preceded the collapse in Texas. In recent months, the largest S&Ls in Charlotte and Raleigh reported huge year-end losses as a result of soured real estate deals.

All of this has serious implications for who will own homes and land in the South. As the savings and loan crisis has unfolded, the housing crisis has worsened. Since 1974, the number of homeowners under the age of 25 has dropped by 40 percent. What’s more, those who do manage to get home loans are more likely to be white than black, as S&Ls continue to deny home loans to black applicants solely on the basis of race.

The warning signals are widespread. Boarded-up homes abandoned by bankrupt S&Ls stand empty in the neighborhoods of Little Rock. Homeless people swell the streets of Atlanta. The government auctions off repossessed property in Florida and Texas to overseas investors to pay off depositors of insolvent thrifts. In the words of U.S. Representative John Bryant of Texas, “America is selling off its family jewels to pay for a seven-year night on the town.”

Incredibly, the Bush bailout plan says nothing about housing, nothing about restoring the S&L industry to its original purpose. Taxpayers are being asked to pay billions to shore up a system that no longer serves their needs. Like the boarded-up houses in Little Rock, the financial system that helped most people gain their piece of the American Dream — a home — has simply been abandoned.

In many ways, the financial industry today resembles the nuclear power industry. It appears complicated, technical, beyond comprehension. It operates with little supervision, and it generates huge profits for a select few. The government lends a hand with tax breaks and direct aid — and tells us to leave our worries to the experts. And like the nuclear power industry of the past decade, the financial system has suffered a complete meltdown — one that has driven many people from their homes and forced many more to live on the streets.

But just as the environmental movement proved it is possible to penetrate the scientific jargon that enshrouds nuclear power, we must now educate ourselves about the closed-door dealings of high finance. The success of the environmental movement reminds us that we not only can understand the intricacies of the financial industry — it reminds us that we must understand them. It is our willingness to look the other way that allows the status quo to proceed unchecked.

In the final analysis, the savings and loan crisis is about the most fundamental issue of all: we are, in essence, talking about the capital in capitalism. Who controls our money? How is it spent? Who is given credit? Who pays off the debts? In an economy where public priorities often follow the flow of private capital, such questions underlie every issue — struggles for decent housing, a clean environment, good jobs, safe workplaces, better education, day care.

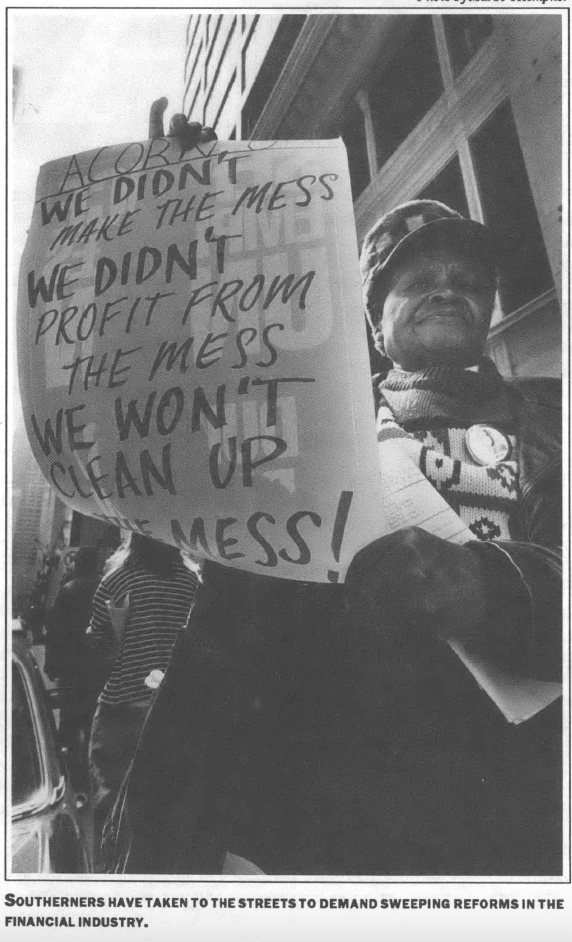

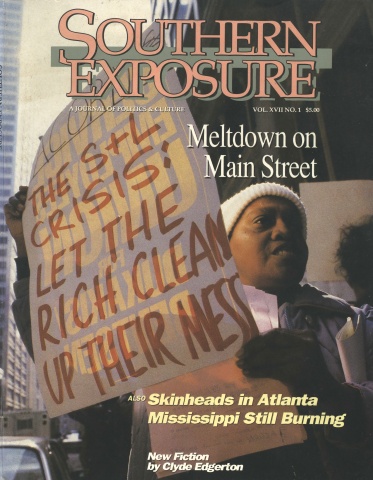

Like every crisis, this one offers us an opportunity to reform the system — a chance to bring a measure of democracy to the world of high finance. Just as the banking crisis of the late 1800s ignited the Southern Populist movement, Southerners today have already taken to the streets over the current financial crisis, placing themselves in the forefront of those demanding sweeping reform. It is the beginning of a new movement — a movement its leaders are calling a campaign for financial democracy.

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.