This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 1, "Meltdown on Main Street." Find more from that issue here.

Richmond, Va. — Oliver Hill had heard enough. T. Justin Moore, the attorney for the Prince Edward County School Board, had been hammering away at Hill’s witnesses in a civil rights lawsuit over school segregation in Southside Virginia. After a New York psychologist testified that segregation was harming black students, Moore asked the witness whether he was “100 percent Jewish.” Then Moore asked another psychologist whether he was aware that the goal of the NAACP was to stir up trouble to call attention to racial segregation.

“Just a moment,” Hill objected angrily. He challenged Moore to name a single place where the NAACP had pursued such a policy. “We unquestionably are trying to break up segregation, and everybody will admit that,” Hill said. “But if he is going to ask the question, let him ask it fairly.”

Moore responded that Hill himself had been quoted in Richmond newspapers after a case involving the segregated Mosque theater “as urging the people in Richmond to create these situations.”

“I dispute that,” Hill said. “And I dispute the fact that even the press reported any such thing. I did say — and I say it now — that I urged people to exert themselves to carry on their rights. Whatever their rights were, under the law, they should press for them. And going to the Mosque, being segregated, is a denial of their rights, and they ought to go there and not be segregated, and refuse to be segregated. And I say it now.”

Hill and his colleagues from the NAACP lost their trial against the Prince Edward County School Board that day in 1952, but they appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Two years later, it became part of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision outlawing school segregation — a decision that wiped away legal justifications for state-sponsored racism that had been developed over more than half a century.

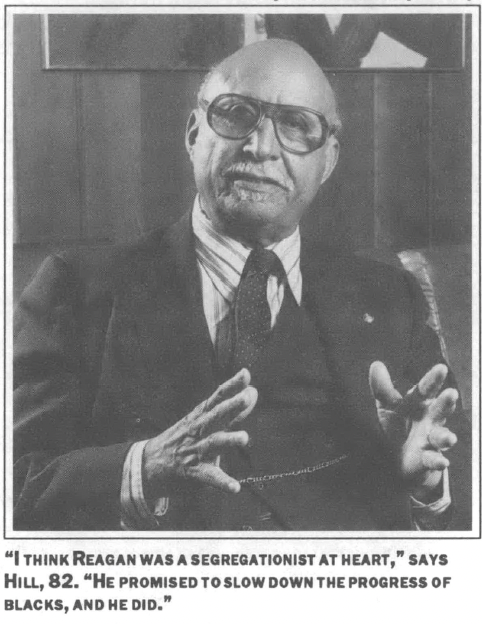

By the time the high court made its historic ruling in 1954, few lawyers had logged more time fighting segregation in the South than Hill, his law partner Spottswood W. Robinson, and his law school classmate Thurgood Marshall. Today, 35 years later, Robinson is a senior federal appeals judge. Marshall is a U.S. Supreme Court justice. Hill, 82, still practices law in Richmond.

Southern Apartheid

For more than half a century, Oliver Hill has been unyielding — and sometimes fiery — in his pursuit of a moderate path to change. Some have called him a troublemaker, but he says he’s never been a rabble rouser. “Standing on a comer whooping and hollering never impressed me,” he once said.

Hill says he went to law school for one purpose only — to prepare himself for a legal challenge to the Southern version of apartheid. He hasn’t tried to tear down the system, preferring to work from within to change it, through the courtroom and the ballot box.

Over the years, Hill’s moderate approach has brought him alternately in and out of favor with Virginia’s white power structure. In 1948 he became the first black this century to be elected to the Richmond city council — but then the 1954 school desegregation decision killed his chances at elective office for several years. Later, as assistant to the federal housing commissioner under the Kennedy administration, Hill denounced the Virginia political machine for closing schools rather than allowing blacks and whites to mix, publicly comparing state officials to the Nazis. Yet by 1969 the Richmond Times-Dispatch, one of the region’s most reactionary newspapers, was praising Hill for his moderation in opposing black separatism and what the paper called “racial extremism.”

These days, Hill’s hometown is a study in contrasts. Richmond has swelled with a population and construction boom. But black poverty and black-on-black crime are rife, making the state capital a murder capital where the newspapers are filled with stories of drug dealers and teenage hit men. Hill doesn’t claim to know what the explanation is, but he does point out that political opposition to true racial equality makes the process of change a two-steps forward, one-step back proposition. “There’s progress,” he said, “but then something comes along.”

Back of the Bus

Oliver W. Hill was born in Richmond in 1907 but grew up across the state in Roanoke, a railroad town in the Blue Ridge Mountains. One of his first memories of racism was when, at about age 9, he was chased by white men who said they were going to cutoff his testicles. He couldn’t tell whether they were joking or not, but the threat terrorized him.

Later, when Hill started playing basketball in the seventh grade, he had to get up at four or five in the morning to move chairs at the old city auditorium so his team could practice. He and his teammates would work out, shower at home, and then head for school. The gym at the white high school was off-limits to them.

When he reached high-school age, Hill had to move to the District of Columbia because there was no black high school in Roanoke. By 1930 he had made his way to Howard Law School, where he came under the sway of Charles Houston, the school’s tough-minded dean. Houston taught his students that any lawyer who was not a “social engineer” fighting for people’s rights was a social parasite. Hill graduated second in his class in 1933, just behind Thurgood Marshall.

From there Hill returned to Roanoke, set up practice, and began working as the point man in the NAACP campaign to force local and state officials in Virginia to provide equal pay for black teachers. At the time, NAACP lawyers were handcuffed by the 1896 Supreme Court Plessy v. Ferguson decision upholding the legality of “separate-but-equal” schools. Unable to attack segregation head-on, Hill and other civil rights lawyers were forced to wage a slow, frustrating battle, pressuring officials to upgrade black schools so they were equal to those for whites.

Hill moved to Richmond after a few years in Roanoke, where it was nearly impossible to make a living as a black lawyer. From the 1930s into the 1950s, he traversed the state fighting for black rights. He packed sandwiches because few restaurants would serve him and stayed with friends because most of the hotels that offered rooms to blacks were third-rate. He usually drove to avoid segregated buses and trains. He and his law partners looked for Esso stations, because an Esso official nicknamed “Billboard Jackson” had made an effort to desegregate restrooms at company filling stations.

Once in the 1940s, Hill got on a bus near Charlottesville and took a seat near the front because it had more legroom. He was the only passenger, but the driver told him: “Get back to the back seat.”

“Get back on the back seat for what?” Hill said.

“Because I told you to,” the driver growled. “You want me to come back and put you on the back seat?”

“That’s what I’m waiting for,” said Hill, a sturdy 6-foot-1.

The driver said he was going to stop and find a sheriff. Hill told him: “You’re the driver and you can do what you want.”

They continued to exchange words until the bus arrived in Richmond and Hill got off.

Jim Crow Schools

In Sussex, a poor county in southern Tidewater, Hill took up the case of children who lived 40 miles from the nearest black school. The county did not provide them any transportation. He flagged down a white bus driver and asked him if he could drive them to the black school. The driver said, “Hell no.” So Hill loaded the kids into a truck and drove them to the nearby white school. He told the principal he wanted to enroll them.

“I remember the eyes on that guy,” Hill told author Richard Kluger, who recounts the tale in his book Simple Justice. “He ran for the phone and got the district superintendent, who told him, ‘Don’t go lettin’ any niggers in there.”

An early, major victory came in 1940 in a case involving a black teacher in Norfolk. Melvin Alston was earning a salary of $921. White teachers with the same experience were making $1,200. “Before the case was heard in Norfolk,” Hill remembered, “my mother came to Richmond and introduced me to her friends as her son, the practicing attorney. I told one of her friends I was going to Norfolk and told her why and she said, ‘Lord, child, don’t do that. They’ll run you out of here in three or four months.’” That didn’t happen. Instead, a federal appeals courts ruled that the salary difference was unconstitutional.

By the late 1940s, the NAACP’s legal campaign gained steam with a slew of wins in federal court Despite the victories, getting court orders enforced was difficult. Gloucester County school officials responded to an order to equalize schools by putting a brick facade on the pre-Civil War building used for blacks. The NAACP went back into court, and a federal judge fined school board members $1,000 each. When Pulaski County school officials showed similar intransigence, the NAACP said fines were not enough — the group demanded that the schools be integrated.

“That ole judge,” Hill remembered, “he kept saying to us, ‘I will not do it! I will not do it!’ I thought he’d bust a blood vessel.”

In 1950 Thurgood Marshall, by then the head of the NAACP’s national legal drive, decided it was time to put an end to the successful but plodding equalization strategy. Hill, Marshall, and others involved in the battle felt that the piecemeal approach was simply not producing enough results. It was time to challenge the constitutionality of the separate-but-equal doctrine itself.

“After a while we found that all we were doing was getting just a little bit better Jim Crow schools,” Hill remembered. “A little newer, but they weren’t better.”

NAACP officials were worried that rural blacks might not be willing to go along with the more aggressive strategy, but their concerns proved unfounded. When the group held a meeting at a church in Dinwiddie County to explain the new strategy, more than 400 local citizens showed up.

“There was this old man in the back wearing overalls and he gets up after hearing us out — he looked like he didn’t know beans from Adam — and he says, ‘Mr. Hill, I’ve heard you, and all I want to say is that we’ve known all along that you couldn’t do it this way, a piece at a time, and we’ve just been waiting for leaders to tell us we had to go all the way.’”

The white response to the new plan was somewhat less enthusiastic. In Cumberland County, one school board member said: “The first little black son of a bitch that comes down the road to set foot in that school, I’ll take my shotgun and blow his brains out.”

“Education Robbers”

Prince Edward County was not the NAACP’s first choice for a challenge to the separate-but-equal doctrine in Virginia. Leaders felt a city like Richmond or Norfolk — where racial views were slightly more moderate than in the red-clay country of Southside Virginia — would have been better. But when black students at Moton High went on strike, refusing to attend their cramped, inadequate school, they showed so much determination that Hill and Spottswood Robinson agreed to take their case. “We just didn’t have the heart to tell ’em to break it up,” Hill said.

The NAACP took the county school board to federal court in Richmond. The case was titled Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, because first on the list of plaintiffs was Dorothy E. Davis, a 14-year-old freshman.

When the trial began on February 25, 1952, school board attorney Justin Moore set the tone with his racial slurs and tough cross-examination, asking one black psychologist why “the Negro” wanted to be a “sun-tanned white man.” After a parade of witnesses for both sides and a closing argument by Virginia Attorney General Lindsay Almond, Hill had the last word. He lashed out at those who said “separate-but-equal” schools would help blacks develop talents unique to their race.

“That is foremost in the minds of these people who want segregated schools: Let a Negro develop along certain lines.” Hill concluded. “Athletics — that is all right. Music — fine, all Negroes are supposed to be able to sing. Rhythm — all Negroes are supposed to be able to dance. But . . . we want to have an opportunity to develop our talents, whatever they may be, in whatever fields of endeavor there are existing in this country. . . . I submit that in this segregated school system, you don’t have that opportunity.”

The three-judge panel that heard the case disagreed. It ruled that school segregation rested not upon racism but upon the social conventions of Virginia. “We have found no hurt or harm to either race,” the judges said. The NAACP appealed, and the case joined similar lawsuits from Kansas, South Carolina, and Delaware before the U.S. Supreme Court under the title Brown v. Board of Education. On May 17, 1954, the court outlawed school segregation entirely. Separate schools, the justices ruled, were “inherently unequal” because separating black children from white children generated a feeling of inferiority “that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to be undone.”

Since his term on city council in the late 1940s, Hill had been harassed by threatening phone callers and letter writers. It got to the point where he automatically took the phone off the hook every night just before he went to bed. After the Brown decision, however, the abuse escalated. Someone burned a cross in his yard, and, once while he was away overnight, police officers, firemen, and an undertaker were sent to his home to tell his wife he was dead.

The white power structure in Virginia also turned its back on Hill. When he had run for the state house in 1947 (a close loss) and for City Council in 1948 (a win) and in 1950 (a 44-vote loss to a white candidate), Hill had always made it a point to talk to every civic club he could, black and white. The response at white groups was usually polite, even though they had never seen a black politician before. The master of ceremonies would say: “We’ve got a Negro candidate here. We ought to listen to him just like the others.” When Hill made a second try for the state house after the Brown decision, however, white civic groups let him know he wasn’t welcome at their meetings.

The official response to the Brown decision in Virginia was first to stall, then to defy. The political machine of Senator Harry Byrd Sr. responded with “massive resistance” — closing facilities in many parts of the state rather than allowing white and black children to attend school together.

In the spring of 1961, only 10 days after being named an assistant to the federal housing commissioner, Hill returned to Prince Edward County. He stood on the lawn of Farmville’s white-columned courthouse and told a rally of more than 1,000 people that the officials who had closed Prince Edward’s schools were “education robbers” guilty of “crimes against humanity” much like those inflicted on the Jews by Adolf Hitler. Hill said the only difference between the school closings and Nazi crimes was in degree, the difference between a swindler who preys on widows and orphans and a highwayman who assaults and robs his victims.

Reagan and Yuppies

In recent years, Hill has handled few civil rights cases, leaving that to younger men like his law partner Henry Marsh, a city councilman. The emotional element of such cases is too much for him to handle these days, Hill said. “You don’t feel like getting yourself riled up.”

He has stepped back into the battle from time to time, though. In 1980, at age 73, he showed up at a congressional hearing to support the proposed appointment of the first black federal judge in Virginia. Senator Harry Byrd Jr. — the son of the man who led the state’s “massive resistance” to integrated schools — opposed the appointment.

Hill’s voice cracked with emotion as he talked about Virginia’s history of racism. “We have distinguished members of the bench all over the country, but not in Virginia,” he said. “In my generation, everybody who was really ambitious politically left Virginia.”

These days, Hill says, he’s worried by a disturbing trend: “You’ve got so many yuppies now, they’re just as bad as people 35, 40 years ago,” he said. Young whites have been attracted by Ronald Reagan’s “reverse-discrimination baloney,” Hill said. “I think Reagan was a segregationist at heart. The only thing Reagan was successful at — he promised to slow down the progress of blacks, and he did.”

During the Reagan years, Hill’s law firm has kept up the battle. His partner, Marsh, was on the losing side in the U.S. Supreme Court decision last January that struck down a Richmond program setting aside some municipal construction business for minorities. In Richmond, a city whose population is more than half black, only one percent of city construction business went to minorities before the set-aside program began.

“There’s no way on God’s green earth that blacks will be able to show that people have individually discriminated against them before someone can be expected to take any action,” Hill said. He sees hope, though, in the success of Jesse Jackson’s “Rainbow Coalition” and in Douglas Wilder’s 1985 election as lieutenant governor of Virginia. Wilder, the first black elected to statewide political office in the South since Reconstruction, used a grass-roots strategy that was reminiscent of the way Hill reached out to black and white civic clubs when he was running for city council.

These days, Hill said, it’s not just lawyers who must be “social engineers” — the ideal he learned at Howard Law School. It’s everyone’s responsibility, black and white.

“The white majority has got to recognize that it’s to their interest — rather than just blacks’ interest — to bring about this cultural change,” Hill said. “My favorite term is: We got to realize that we’re all human earthlings.”

Tags

Michael Hudson

Mike Hudson is co-author of Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty (Common Courage Press), and is a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1998)

Mike Hudson, co-editor of the award-winning Southern Exposure special issue, “Poverty, Inc.,” is editor of a new book, Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty, published this spring by Common Courage Press (Box 702, Monroe, ME 04951; 800-497-3207). (1996)