This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 1, "Meltdown on Main Street." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Shelby, N.C.—Three men entered the Shelby III Adult Bookstore near midnight on January 17,1987 while one waited guard outside. Dressed alike in brown corduroy coats, their faces covered with ski masks, they ordered the five men in the store to lie face down on the floor. Then they shot each man in the head, set fire to the store, and fled.

Two customers and a 19-year-old employee of the bookstore died instantly. Two other customers survived, and one managed to give police a description of the attack.

It was clear from the start that this was no ordinary late-night holdup. The assault had been too systematic, the violence too brutal. At first police speculated that the attack was linked to an organized crime pornography network, but evidence later led them to suspect the involvement of right-wing extremist groups.

Ten months later, Robert Eugene Jackson and Douglas Sheets were indicted on 16 counts in the Shelby attack, including three counts of first-degree murder. Both men were former members of the White Patriot Party, a heavily-armed, neo-Nazi group active throughout North Carolina for the past decade. Their motive, according to an informant, was to “avenge Yahweh on homosexuals.”

Jackson and Sheets are scheduled to go on trial in Shelby this spring, and the proceedings are expected to con-firm that the bookstore killings were far from an isolated incident. North Carolina has led the nation in racist organizing and bigoted violence since 1983, and the Shelby case marks the second time this decade that Klansmen and Nazis in the state have been indicted for mass killings. The trial reveals some of the new incarnations of old hate ideologies rampant throughout the region, shows how farright groups have targeted gay people, and offers a warning about the deadly effect of white supremacist organizing when it is allowed to go unchecked.

NAZI-KLAN UNITY

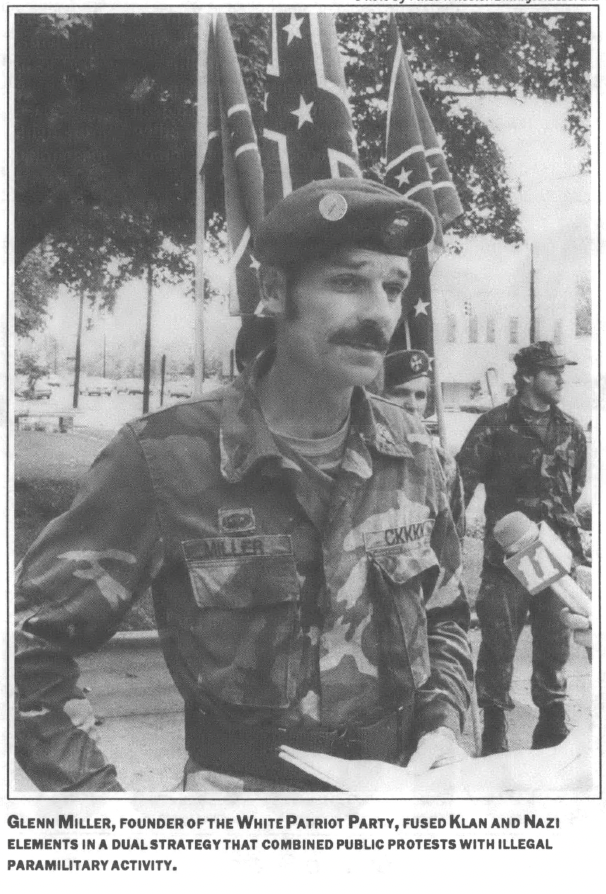

Glenn Miller, the founder of the White Patriot Party, was apparently nowhere near the Shelby III on the night of the executions, nor has he been held legally liable for the murders. According to key witnesses, however, the organization he built was directly responsible for the deaths that night.

The White Patriot Party had deep roots in North Carolina. A Green Beret who served two tours of duty in Vietnam, Miller was discharged from the Army in 1979 at Fort Bragg, North Carolina for distributing a white supremacist newspaper on base. Over the next decade he worked full-time as a white supremacist organizer, apparently supporting himself in part on his Army retirement pay.

Miller worked briefly with Harold Covington, the Nazi leader who helped organize the group that killed five anti- Klan demonstrators in Greensboro in 1979. Covington ran for state attorney general on the Republican ticket in 1980, garnering 43 percent of the vote. His call for a “Free State of North Carolina” was later echoed in much of Miller’s material. Suspected of being an informant, he fled to South Africa in 1981.

Miller turned away from Nazi imagery, founding the Carolina Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in 1980. “People are not receptive to the swastika,” Miller explained. “White People have been brainwashed for the last 35 years that the Nazis were somehow related to communism.”

The Carolina Knights reflected the dominant tendency on the far right in the 1980s: the fusion of Klan and Nazi elements into a deadly new breed intent on building a mass movement ofwhite people and taking over the federal government, by force ifnecessary. Like other ultra-right leaders around the country, Miller pursued a double strategy that combined mass organizing through media, marches, and electoral campaigns with illegal paramilitary activity.

Miller began one of many campaigns for elected office in 1982 to show “that the Ku Klux Klan is working peacefully within the system” as well as to gain “favorable and free publicity.” Unlike other “scalawag politicians,” he was clear about the source of the country’s problems: “inferior, violent-prone, parasitic minorities.” He insisted that the Carolina Knights was a law-abiding organization, but added: “We are building a mass White citizens militia, complete with legal firearms to protect ourselves.”

To Miller and the Carolina Knights, “protection” meant more than a gun in the glove compartment— it meant stockpiling heavy weapons and conducting illegal paramilitary training. According to the testimony of ex-Klansman James Holder, active military personnel from Fort Bragg and Camp Lejeune took to the woods of Lee County in 1982 and 1983 to help train Klansmen in hand-to-hand combat, escape-and-evasion, ambush, river crossing, and seek-and-destroy missions using AR-15 and mini-14 rifles, shotguns, pistols, and artillery simulators.

Holder testified that the purpose of such training was to overthrow the government and establish a Nazi “United State of Carolina.” State law enforcement officials routinely accepted the Klan’s word that their operations were legal.

The group soon put its lethal training into practice. When Bobby Person, a black prison guard in Moore County, tried to apply for a job as a sergeant in 1983, Carolina Knights visited his home in “Special Forces” fatigues, burned a cross on his lawn, and threatened his family at gunpoint. Person filed suit against the group through the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Alabama.

ENTER THE ORDER

In 1984, the Carolina Knights began to peak. The home-grown operation started to converge with national trends, and Southern Klansmen found themselves in league with neo-Nazi hate groups across the country.

Chief among these national allies was The Order, the white supremacist group that conducted a terrorist campaign based in Seattle in 1983 and 1984. Following the scenario laid out in The Turner Diaries, the novel by neo-Nazi leader William Pierce, the group bombed a synagogue and robbed several armored cars, escaping with $4 million in cash to distribute to extremist leaders around the country.

According to court testimony, some of the money found its way to Glenn Miller and the Carolina Knights. Robert Mathews, the founder of The Order, reportedly visited Benson, North Carolina —Miller’s hometown —in August 1984. Another Order member, Bruce Carroll Pierce, testified Miller had received $300,000 from The Order robberies that fall. (Pierce later retracted his statement).

That October, the Knights held a heavily armed rally in Robeson County. The event drew 300 participants, a sharp increase over previous rallies. Expensive new weapons seemed to indicate a recent influx of cash. Miller changed his group’s name to the Confederate Knights and announced plans to organize new chapters throughout the region. He also unveiled a computer link-up with an information network run by the Aryan Nations, the neo-Nazi group that had given birth to The Order.

THE ROAD TO SHELBY

In 1985, Miller made good on his promises of expansion. For starters, he changed the group’s name again—this time to the White Patriot Party—hoping to enshroud its Klan robes in the colors of the American flag. “We want to reach the minds and hearts of our people, and we cannot do that under the name Ku Klux Klan,” he explained in a press release.

The White Patriots began moving into older Klan turf in the mountains of western North Carolina. There they found fertile ground—and their efforts in Shelby were a case in point.

On June 15,1985, the White Patriots caravanned from Shelby to Forest City to Gastonia in a major “tri-city rally.” That night, heavily armed with pistols, shotguns, semi-automatic and bolt-action rifles, they rallied in Cliffside, not 10 miles from the Shelby III Adult Bookstore.

“We’re going to get our country back,” Miller told his troops. “We hope to keep bloodshed to a minimum, but anyone that gets in the way is going to be sorry.”

Zane Saunders, a reporter for the Forest City Courier, covered the caravan and rally. “These are not the words of someone who plans to use weapons just for defensive purposes,” Saunders wrote. “The White Patriot Party is wrong. Dead wrong. It is also fanatical. Mix the two and you have an explosion just waiting to happen.”

The organizing efforts in the tri-city area paid off. The Confederate Leader announced White Patriot “dens” with phone units in three local towns. In the fall a local Patriot, Jimmie Bailey, ran for the Shelby school board, supported by a spate of letters from White Patriots to local newspapers. “I choose to keep [my eyes] open, and to keep trying to save my dying race, the white race,” one supporter wrote. “If that’s hate, please tell me what love is.”

The Shelby Star editorialized about the danger of Bailey’s candidacy, and local Presbyterian minister John Bell called on the community to “oppose openly and publically the principles and activities of the KKK.” Three days later he opened his mail to find a picture of a man hanging from a tree with the caption: “DEATH! to the Traitors, Communists, Race Mixers and Black Rioters. It’s time for old-fashioned American Justice.” Bailey lost the election by a resounding margin—but Shelby was only one community where the White Patriots had made inroads. By the end of 1985, the group reported dens in 16 North Carolina towns and seven other states, including Georgia, South Carolina, Florida, and Tennessee.

GOING UNDERGROUND

Finally, in 1986, the suit the Southern Poverty Law Center had filed for prison guard Bobby Person brought Miller into federal court. An ex- Klansman testified that he had sold the White Patriots $50,000 in illegal arms, including plastic explosives, anti-tank rockets, land mines, and guns and ammunition. Miller was found guilty of two counts of contempt, and the Patriots disbanded in October. U.S. Attorney Sam Currin reported that the group was “disintegrating,” but warned of the formation of a “smaller but more extreme element.”

On January 5, 1987, federal officials indicted Robert Jackson and four other White Patriots for conspiring to obtain illegal weapons. Twelve days later white supremacists attacked civil rights marchers in Forsythe County, Georgia—and the Shelby bookstore slayings took place that same night.

Three days after the murders, U.S. Attorney Currin spoke to a reporter. “For too long the White Patriot Party was ignored by the state of North Carolina,” he said. “A mentality developed among the White Patriot Party members that they could get away with anything.”

When the trial for arms conspiracy opened on April 6, Jackson didn’t show up and Doug Sheets failed to answer a subpoena. The jury found Jackson guilty of conspiring to buy stolen military weapons. Currin said the convictions marked the end of White Patriot activities in North Carolina.

But Glenn Miller was not through. With reports circulating that he would soon be indicted by an Arkansas grand jury, Miller jumped bond and drove to Oklahoma to recruit Jackson and Sheets to join him underground.

On April 15, Miller sent a “Declaration of War” to at least 3,000 white supremacists. “I declare war against Niggers, Jews, Queers, assorted Mongrels, white race traitors, and despicable informants,” the declaration read. “War is the only way now, brothers and sisters.... So, fellow Aryan warriors, strike now. All 5,000 White Patriots are now honor bound and duty bound to pick up the sword and do battle against the forces of evil.”

The fugitives summoned Bob Stoner, a fellow White Patriot, to Louisiana to be their driver. But what Stoner saw and heard scared him. The group talked of blowing up a synagogue in the Midwest and killing 50 blacks in Atlanta. Jackson and Sheets also bragged about the Shelby attack. Stoner returned to North Carolina badly shaken, and asked Pat Reese, a veteran reporter for the Fayetteville Observer, for help. Reese contacted law enforcement officials, and S toner led them to Miller in return for limited immunity.

Shortly before dawn on April 13, law enforcement agents surrounded a trailer in a mobile home park near Ozark, Missouri. They fired tear gas, “prepared fora violent shootout,” as agents later explained. Miller, Jackson, Sheets, and another White Patriot surrendered without firing a shot. Officers confiscated a “small army” of pistols, flack jackets, several thousand rounds of ammunition, shotguns, rifles, hand grenades, plastic explosives, pipe bombs, and $14,000 in cash.

They also found a police scanner tuned to the frequency of Shelby, North Carolina, along with ski masks and cotton clothes similar to those used in the bookstore murders.

“TERROR DOWN THE ROAD”

A few months later, Stoner told a federal grand jury that the Shelby attack had been committed by white supremacists bent on destroying what they believed was a homosexual hangout. He also reported that two local persons helped plan the murders, including the wife of one of the gunmen who remained at home listening to a police scanner.

Glenn Miller also agreed to testify against Jackson and Sheets in exchange for reducing his prison sentence from 100 to five years. He admitted he had received $200,000 from The Order in 1984 and told prosecutors that he paid Jackson and Sheets $7,000 to $8,000 each when they arrived from Oklahoma to work as fulltime organizers for the White Patriot Party.

Sheets had apparently urged Miller to standardize his “rag-tag Klan” into a more uniform paramilitary operation and admitted to training an “unorganized state militia” in target practice, woods survival training, river crossing, and booby traps. He also said he had bought 3,000rounds of ammunition, 40 to 50 pipe bombs, and plastic explosives to train the militia.

The break-up of the White Patriot Party coincided with federal prosecutions of Order members nationwide. As a result, the remaining leaders of the old hate groups shifted their focus from the orchestrated guerrilla tactics of The Order to the sporadic street violence of the Nazi Skinheads. Tom Metzger, a California Nazi and one of the few national leaders untouched by federal indictments, began actively recruiting Skinheads, and the violent street gangs are now surfacing in towns across the South.

The remaining Nazi and Klan leaders also began to piece together what was left of their shattered movement About the time Glenn Miller entered federal prison, his Nazi mentor Harold Covington returned to North Carolina and began organizing the Confederate National Congress, emphasizing the Southern nationalist themes he had taught Miller.

Leonard Zeskind, research director for the Atlanta-based Center for Democratic Renewal, explains that far-right groups regionally and nationally are going through a period of shifting alliances, trying to reassemble the pieces fragmented by federal prosecutions. In the near future, he predicts, they will abandon mass politics in favor of smaller, more hard-core groups.

“Shelby arose out of a dynamic of the previous period more than as a precursor of the next period,” Zeskind says. “For the next few years, far-right organizing will take clandestine forms that by their nature will result again in terror down the road. But the immediate mass violence will come from groups like the Skinheads, with indiscriminate attacks, while the hard core people like Harold Covington regroup.”

Tags

Mab Segrest

Mab Segrest is a writer, teacher, and organizer who lives in Durham, NC. She has written two books, My Mama's Dead Squirrel and Memoir of a Race Traitor. She is working on a third, Born to Belonging. This is excerpted from an essay that appeared originally in Neither Separate Nor Equal: Race, Class and Gender in the South, edited by Barbara Smith (Philadelphia: Temple, 1999). (1999)