Abolition Then and Now

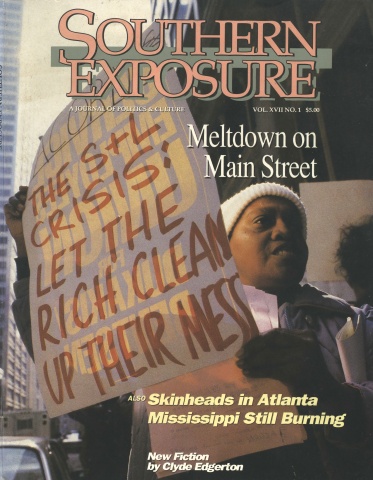

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 1, "Meltdown on Main Street." Find more from that issue here.

When the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty held its eighth annual conference in Dallas, Texas last November, Bruce Ledewitz, a law professor at Duquesne University, sparked a lively debate by comparing the movements to abolish slavery and the death penalty. He revised his comments for Southern Exposure.

Times are bad for the movement to abolish the death penalty, and they are likely to get worse. Opinion polls show enormous public support for the death penalty. Politicians are now even more likely to shun us following Michael Dukakis’ disastrous experience opposing the death penalty. Even the courts, long our movement’s most reliable lever of power, are showing signs of fatigue and a lack of interest in the death penalty.

In the midst of such unpromising prospects, I would like to focus attention on the efforts of the original abolitionists — the movement to eliminate slavery from the United States between 1820 and 1860. Although abolishing slavery differed markedly from our efforts, we might well benefit from considering the success of a kindred movement founded on the principle that all human life is sacred.

My basic message is one of hope. Through perseverance and dedication, the abolitionists succeeded — succeeded in far less favorable circumstances than we face in our effort. And part of the reason they succeeded was because of the diversity of their movement. Although united in a common goal, many abolitionists worked independently of each other, pursuing different messages and tactics. This multifaceted mass movement was their greatest strength; their own disunity actually helped build anti-slavery opinion.

To appreciate the enormity of their success, consider how unpopular abolition was originally. Slaves and free blacks were scorned by overwhelming majorities in both the North and South. Furthermore, the entire Southern economic and social system was premised on slavery, and Northern financial interests also profited from human bondage.

The abolitionists, by contrast, were few and isolated. So unpopular were they that throughout the 1830s, abolitionist lecturers were threatened by mobs wherever they spoke. In fact, the first abolitionist convention in Philadelphia in 1833 took no lunch breaks because of fear that delegates would be attacked if they left the building.

The law was also on the side of institutionalized racism and economic self-interest. It was accepted legal theory in the 1830s that the U.S. Constitution protected slavery in the states and that Congress had no authority to interfere. Thus, with Southern legislatures controlled by white planters and their allies, there was no government mechanism empowered to abolish slavery even if public opinion had turned against it.

In view of these obstacles, it is remarkable that by 1860 the abolition movement had succeeded in convincing a substantial segment of the public that slavery was wrong. This success should give us hope. After all, the abolitionists were much further from their goal in 1820 than we have ever been. The death penalty, for all its popularity, remains a side issue for almost all of its proponents. If we can muster the determination and patience of the abolitionists, we can anticipate the eventual end of the death penalty.

But it is not enough to match their commitment — we must emulate their thoughtfulness as well. The abolitionists developed several different approaches within their movement, fostering a diversity that sometimes sparked conflict and splintering. They never achieved organizational unity, yet their movement did not appear to suffer. Indeed, their diversity and conflict forced them to be clear about their differences.

We in the anti-death penalty movement also have some serious disagreements over priorities. We should consider the different approaches of the abolitionists, and debate our differences as they debated theirs.

Back to Africa

The first important movement among the abolitionists was colonization, which attempted to persuade slaveholders to free their slaves and then to transport them to colonies in Africa. The colonization movement had the advantage of reassuring the racist, white majority that they would never have to grant political and social equality to blacks. Sincere proponents of colonization knew they were condemning thousands of slaves to years of continued servitude, yet they felt their slow progress was the only way to end slavery.

We in the anti-death penalty movement have a colonization position, too — we call it life imprisonment without parole. Like colonization, life without parole reassures the majority that ending the wrong will change the status quo very little. Like colonization, life without parole eliminates much of the need to persuade an unwilling majority to see the wrong for the serious evil it is. Like colonization, life without parole does tremendous and unjust harm to the very people it seeks to help.

And like colonization, life without parole will probably be insufficient in itself to end the death penalty. By the 1830s, the abolition movement came to see colonization as legitimizing the assumptions of slavery. Life without parole may eventually be seen in the same light.

Nevertheless, colonization did achieve one crucial success: it kept abolitionism alive through politically difficult times. Perhaps, then, in our current, difficult times, life without parole can do the same for us. If so, we should make far more of it than we do. In other words, if we need it now, we should use it effectively.

To use life without parole to effectively undermine the death penalty, however, we would have to oppose commuted sentences and strengthen the rules against parole. Reducing the sentences of convicted murderers seriously undermines the life without parole argument. To show the public we are serious about life without parole, we would have to advocate constitutional amendments in each state to eliminate the possibility of parole. Most of us in the movement would dispute that strategy — and such a dispute would help clarify our strategic disagreements.

The Law

The second approach the abolitionists used was a legal strategy that challenged the prevailing view that the Constitution was pro-slavery. Legal critics like Alvan Stewart and Lysander Spooner argued that the Constitution, properly interpreted, prohibited slavery and empowered Congress and the courts to end it Although the legal critics played a small role within the movement, they were important in the adoption of the Civil War amendments outlawing slavery.

Our movement, by contrast, has put many of its eggs in the legal basket — and for good reasons. Unlike the abolitionists, we have had some successes in the courts, and legal work in individual cases has saved many lives.

But, as in the case of life without parole, we have not considered fully how the legal strategy might contribute to the elimination of the death penalty. If we wish to use legal tactics more effectively, we must use law review articles to press the courts to interpret the Eighth Amendment ban against “cruel and unusual punishment” as including the death penalty. And like the legal abolitionists, we must press Congress to consider a bill to the same effect. The congressional hearings on such a bill would allow us to present our constitutional theory and perhaps generate judicial support as well.

The Ballot Box

After the 1840s, many abolitionists turned to political organizing to end slavery. It was this effort that ultimately gave rise to the Republican Party in 1854. Although politicians refused to get too far ahead of Northern public opinion and seldom condemned slavery as immoral, the political approach proved highly successful in the end. Arguments directed to Northern self-interest helped keep slavery out of the Western territories, and political organizing helped elect an anti-slavery presidential candidate in 1860.

Although our movement has enjoyed only very limited success in the political arena, we have won a few short-term victories. Arguments directed at cost helped convince wavering legislators to vote against the death penalty in Kansas, and joining forces with the Georgia Association of Retarded Citizens exempted the mentally retarded from death sentences. These were important accomplishments, and represent a degree of political skill the abolitionists would have envied.

But opponents of the political approach asked the Republicans in 1854, “Will keeping slavery out of the territories eventually extinguish it?” The answer for many abolitionists was no. For us as well, political organizing and short-term victories do not bring abolition closer — not without an accompanying fundamental change in public opinion.

The Moral Crusade

The abolitionists came to recognize that the success of their political organizing depended on their ability to convince the white majority that slavery was wrong, and so they developed powerful secular and religious crusades that inspired massive direct action against slavery.

The leading secularist was William Lloyd Garrison, a notorious anti-cleric and the nation’s strongest voice for immediate emancipation. The Garrisonians were the most militant wing of the abolitionists. They viewed the government as pro-slavery, and urged citizens to refuse to cooperate with the state. They condemned the Constitution as an “agreement with hell,” refused to vote or pay taxes, and called on judges to resign rather than cooperate with slavery.

The religious wing of the moral crusade shunned the radical rhetoric of the Garrisonians, but they shared the insight that slavery was primarily a moral issue and decided to take direct action to end it. The result was the largest, longest-running illegal conspiracy in the history of the United States: the underground railroad. The religious crusaders committed serious federal felonies, sometimes in public, and some later turned to violence and rebellion to free slaves.

What gave the moral wings of abolitionism the impetus to act against the status quo, whether by non-cooperation or by criminal resistance? It was their clear moral message that slavery was wrong. The religious wing based their argument against slavery on the Bible, which represented a common moral vocabulary at the time. Their message of the cruelty of Southern slavemasters and the innocence of the slave eventually swept public opinion.

Compared to the abolitionists, however, our moral crusade has been relatively unsuccessful. The reasons for this failure are complex, but at its heart is the fact that slavery was a relatively simple moral issue compared to the death penalty. The fundamental moral question of whether anyone deserves to die for murder has not yet been resolved. Even among ourselves, we differ on the nature of our opposition to the death penalty. Thus far, a unifying moral principle has eluded us.

Our failure to define a simple and strong moral position is related to the debate taking place now in our movement concerning civil disobedience. If 2,100 people were suddenly rounded up at random and threatened with death by our government, many of us would take whatever action necessary to stop those executions. Yet our deep unstated ambiguity about the depth of the moral evil we face makes us unwilling to act in such a radical fashion to save the lives of those currently on death row. Put simply, many of us, and I include myself, can live with the death penalty in a way that many of the abolitionists could not live with slavery.

We need to clarify the nature and depth of our opposition to the death penalty. We must understand what we oppose before we can decide whether we are willing to violate the law. A law that kills vicious criminals does not call for civil disobedience, but a law that kills human beings calls for just such actions.

The only way I see for us to deepen our commitment to abolishing the death penalty is to see ourselves as more than a special-interest group pleading on behalf of a small minority of convicted killers. We must see ourselves as part of a larger movement — a movement to create what George Bush, of all people, called a “kinder, gentler nation.”

We may assume that a world dedicated to militarism, heedless of the environment, unwilling to feed and house the poor, a world that blinds animals to make perfume — that such a world is not going to be particularly concerned about 2,100 murderers about to lose their lives. I am not suggesting that we be other than a single-issue movement — only that we should see the issue that unites us in the widest possible context.

To broaden our perspective, I believe that we must seek a forthright dialogue with the largest movement of social protest in America today — the pro-life movement. The pro-life movement not only controls an entire political party — the Republicans — it is also founded on the proposition that all human life is sacred.

I realize, of course, that the pro-life movement does not oppose the death penalty, but a growing number of pro-life activists advocate linking opposition to abortion with opposition to the arms race, poverty, and the death penalty. Some pro-life leaders, like Joan Andrews, have opposed the death penalty forcefully and publicly, and groups like Feminists for Life of America want to broaden the movement beyond its conservative base.

Obviously, there are good reasons that we have stayed clear of the pro-life movement. An overwhelming majority within our own movement is passionately pro-choice, and will not tolerate any coalition-building that might threaten the constitutional right of women to choose abortion. Nevertheless, in order to succeed, I believe we must understand ourselves as part of a larger whole of social transformation; we must seek out common ground with all those who envision a less violent world.

There will never be a broad movement in America that celebrates life in all its fullness until abortion is squarely faced. We say human life is sacred. So do they. In order to reach literally millions of Americans who ought to be with us and may one day be, we must speak of life to them and know that they will speak of life to us.

No doubt such a move will spark strong debate within our own movement — and such a debate will be healthy, regardless of the stance we take toward the pro-life movement. When the original abolitionists began to see their movement in the broadest perspective, they found themselves in fundamental disagreement. Their earlier unity — a unity made possible by their small size and inattention to their differences — was shattered. But out of the disagreement emerged a multifaceted movement that embraced many more people and was capable of putting slavery on the road to extinction.

We may fragment like the abolitionists — or we may forge a stronger unity. Whatever the outcome, though, whether our unity suffers or not, we must deepen and broaden our message if the death penalty is ever to be ended.

Tags

Bruce Ledewitz

Law professor at Duquesne University. (1988)