Winning at Any Cost

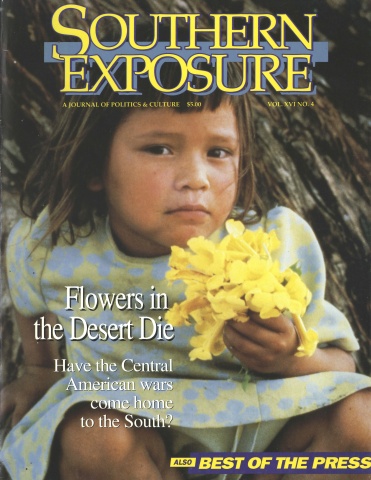

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 4, "Flowers in the Desert Die." Find more from that issue here.

From October 11 to 18, 1987, the Louisville Courier-Journal exposed widespread corruption in state elections. After the series appeared, the legislature and the attorney general each established commissions to investigate the election process. As a result, the Kentucky General Assembly passed an omnibus election-reform bill.

Louisville — Kentucky’s political and electoral system is being poisoned by vote-buying, illicit cash, legalized bribes, public apathy, and officials unwilling or unable to bring about change. The rights of individuals are frequently subordinated to those of special interests who view the state capitol at Frankfort and the county courthouses as their personal fiefdoms and who contribute to political candidates and parties in return for favors.

In an era of skyrocketing campaign costs, wealthy politicians have a significant advantage over those of average means. Poorly financed citizens’ groups have little chance against big corporations, their lobbyists, and political action committees. Regulation of the campaign-finance system is weak, and efforts to strengthen it have been sporadic and largely unsuccessful.

The constitutional guarantees of free and fair elections have been subverted to vote-buyers, vote-sellers, and shortsighted politicians who collectively taint a public office even before its occupant is sworn in. As a result, public confidence in state and local governments and the officials who run them has been damaged, undermining their ability to function effectively and efficiently.

In short, a year-long investigation by the Courier- Journal found a political system corrupted from top to bottom by money. “The excessive amount of money in campaigns, and where it’s coming from, is perverting the system,” said state Representative Joe Clarke. “It’s coming from special interests . . . and the public interest is rarely served.”

The newspaper found:

♦ The skyrocketing cost of political campaigns is increasing pressure on candidates to compromise themselves. Campaigns for governor, made ever more costly by such things as television advertising and sophisticated polling, are financed substantially by contributions given in return for promises. The price tag on this year’s governor’s race is likely to be $15 million, compared to $2 million in 1967.

There are no limits on what a candidate can raise and spend, and state jobs, board seats, and contracts have been given to favored friends and loyal patrons in exchange for generous donations. Shortly after Governor Martha Layne Collins took office in December 1983, then-Transportation Secretary Floyd Poore, one of her top fundraisers, submitted a lengthy list of supporters who were in line to get state positions.

State courts have held that it isn’t illegal to promise a state job in return for a contribution or other support in a political campaign. And it apparently is also legal to promise contracts and seats on boards in exchange for contributions.

♦ The blessed act of giving as a prerequisite for getting is particularly prevalent in the case of architects, engineers, and others who do business with the state under personal-service contracts. Although state officials say these non-bid contracts are bestowed on merit, evidence abounds that the process is in fact highly politicized. And the bottom line is that major contributors to successful campaigns and political parties are very often rewarded.

A survey by the newspaper of roughly 70 architects and engineers showed that more than two-thirds of those who would voice an opinion — 31 of 45 — believe political favoritism influences contract awards. Perhaps that is why architects and engineers are roughly 60 percent of the more than 200 members of the Democratic Party’s Century Club, willing to pay $1,000 or more a year to sip cocktails with the governor and other high state officials. Five engineering firms that have received more than $50 million worth of personal-service contracts under the Collins administration donated a total of at least $85,000 to her 1983 campaign or to the Democratic Party in the ensuing years.

♦ Regulation is sorely lacking. Kentucky’s Registry of Election Finance is just that — a repository where some of the state’s political spending is recorded. As an investigative and enforcement agency, the registry is impotent, lacking the funds, staff, and laws necessary to do battle with high-powered legions of electoral miscreants. The registry’s executive director, Raymond Wallace, concedes that his agency lacks the resources even to meet the law’s requirement that the campaigns of all state-wide candidates be audited within four years. The registry’s audit of Collins’ 1983 campaign will not be completed until after she leaves office.

♦ The influence of special interests is on the rise. In the last decade, the number of political action committees (PACs) registered in Kentucky has leaped from 93 to 331. The amount of money they gave to political candidates doubled, and the PAC percentage of total donations also rose sharply.

The law provides PACs with a giant loophole. While individuals in Kentucky can give no more than $4,000 to a candidate in any one election, they can give unlimited amounts to PACs, which in turn can give as much as they want to a candidate. Four days before this year’s May primary, four Lexington residents gave a total of $21,000 to Citizens Committed to Better Government. That PAC passed the money on to the campaign of Wallace Wilkinson, who won the Democratic Party’s nomination for governor.

Only after the Courier-Journal brought the matter to the registry’s attention was the PAC asked to retrieve some of the money from Wilkinson and return it to the original contributors. The registry made its request — which it had no power to enforce — on the grounds that the PAC had been used in an attempt to disguise contributions in excess of the $4,000 limit.

PACs are now wholly unfettered by regulation except for a requirement that they file periodic reports with the registry. Occasional attempts to rein them in have been met either by silence or overt resistance in Frankfort. “I don’t see much movement for reform,” Clarke said. “The people who pass the laws are the people who get the contributions.”

♦ Vote-buying flourishes to an extent incomprehensible to the public at large. It is most pervasive in Eastern Kentucky, where it has been an integral part of the political system for generations, but it also occurs in other predominantly low-income areas of the state. Those who should know — profiting politicians and the vote-buyers themselves — estimate that up to half the votes cast in certain precincts in some elections are bought. Between 1980 and 1982, the state police investigated allegations of vote fraud in 18 counties and concluded that illegal practices were large-scale, widespread, and organized.

♦ Illicit cash in huge amounts plays a vital role in the electoral process. No one knows how much cash flows in an election year, but politicians who take it and spend it estimate that the actual cost of some races is 50 percent to 100 percent higher than the figures actually reported.

The difference is cash: cash contributed because the donors either got something illicit in return or else didn’t want their largesse publicized; and cash spent by politicians on such illegal activities as buying votes. “You cannot win an election up here without election day money, and cash is all they use,” Letcher Circuit Judge F. Byrd Hogg said. Cash donations in excess of $100 are illegal.

During his successful 1985 campaign for Perry County judge-executive, Sherman Neace reported spending more than $107,000. Neace doled out nearly $92,000 of that amount in cash to about two dozen political operatives, who were told only that he wanted their support and to carry their precincts. Darrel Fugate, one of the recipients and a well-known election manipulator, admits that he spent the $3,000 Neace gave him to buy votes.

Up in Arms

Unless public attitudes change, changes may be a long time coming. The existing corruption is condoned, if not encouraged, from the precinct level to the governor’s office. Politicians — those responsible for changing the status quo — are the ones who profit from it. “It’ll never change until people rise up in arms,” Hogg said.

Reform-minded citizens who might press for reforms — if only they could conquer the corruption and win public office — are becoming disillusioned and forsaking politics. Consider the case of Pete Shepherd, a Salyersville dentist with two children in the Magoffin County school system. Shepherd decided to run for school board last year but lost in a race that he and others charge was rigged by vote-buyers. Now he vows never to seek elective office in the county again — unless outsiders “run the election.”

Although no organized movement has developed, there are indications that the public would support changes. The newspaper’s poll found that a majority of Kentuckians are concerned about the high costs of campaigns and favor limits on the amounts candidates can raise and spend. A sizable majority also said they think candidates compromise their honesty and integrity at least occasionally in order to obtain campaign contributions.

However, in the past, even modest attempts to alter the system frequently have been thwarted. Curbs on PACs have been rejected, and suggested restrictions on political contributions by engineers aren’t even discussed openly by the profession. At a time when some states were tightening the screws on campaign contributions, the 1986 General Assembly boosted the limit for individual contributions to $4,000 from $3,000.

The same legislative session limited the controversial practice of “post-election fund-raising” — a lucrative tool used by successful candidates to retire campaign debts. But the new law allows the financial harvest to continue until the reaping politician takes office. In the weeks after the May primary, Wilkinson amassed contributions totaling $1.9 million to help recoup money he had lent his campaign. The contributors included lawyers, engineers, architects, and others who traditionally do business with the state.

“I’m outraged by the General Assembly’s passing that statute,” said Owensboro attorney Morton Holbrook, a former registry member. “It’s ideal for laying the heavy finger on people all over the commonwealth.”

Historian Harry Caudill, an Eastern Kentucky native and a frequent and strident critic of the state’s political system, is convinced that the effort to effect sweeping changes must be two-pronged: arousing the slumbering business community to the crucial need for leadership, and blanketing precincts with state troopers on election day.

“We’re locked into a corrupt system, and nobody thinks we can get out of it,” Caudill said. “You cannot believe the audacity of people for whom politics is a way of life. If we don’t get reform soon, Kentucky politics will be the playground of the rich and the bookkeepers who can do things nobody can figure out.”