White Baby

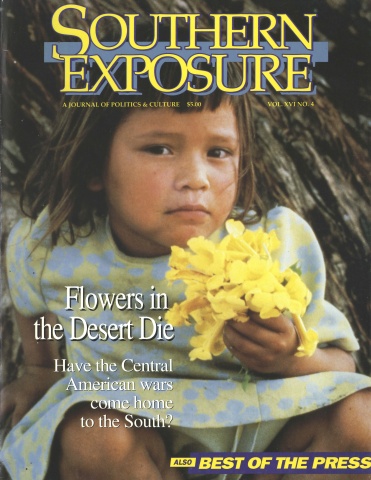

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 4, "Flowers in the Desert Die." Find more from that issue here.

I could not take my eyes off my white baby; he looked like a little old man, his hair as white as the coat of the doctor that held him there. “Lack of pigment,’’ the doctor told me later. He said all kinds of things, all kinds of words, but I just stared at my poor white baby and tried not to cry. Hadn’t I wished myself white at least once in my life? And now my wish had come true in such a mean and twisted way. Poof! Abracadabra! I was sorry that I had ever thought such a thing.

My baby was not hard to spot in the nursery there. I stood and leaned against the wall that faced the big window. Like magic, when they saw me, they wheeled my white baby up to the front row. It made me feel so cold to look at him, cold as December, and I pulled my robe that Everly had brought me as close around my body as I could get it; I dug my toes way down in those thick terry slippers my girls had picked out. He looked like a regular baby, turning his head, crying until his little face turned pink.

An older woman came and stood off to the side, a long-legged teenager clinging to the woman’s arm. They were laughing and grinning, pressing their faces up against the glass. “A new grandbaby,” the woman kept saying and that thin pale girl would say, “a sister” like an echo and the two leaned together and laughed. The woman was not dressed for a hospital visit; she wore pedal pushers and a man’s work shirt, her thick gray hair pulled back and tied with a scarf. I tried not to listen in on them but it was hard because they wanted everybody to know why they were there. “I came as fast as I could,” the woman said to me and held out her foot to show a dirty sneaker. “I was working in my yard and I didn’t even take time to change my shoes. It’s my oldest girl’s baby, her second, this is her first.” The thin girl turned and grinned at me.

Just yesterday, me and Everly were in such a state. He came to pick me up and he never even took off that heavy old belt with all of his telephone wire tools. I had a curler on the top of my head and didn’t even remember it until I saw myself in those big mirrors and then I didn’t even care.

“There must be some mistake,” is what Everly said when the doctor held up our little baby, and I wanted to ask him how could it be a mistake when he just now saw that baby come out of me. I didn’t have the breath to say a word right then; I just leaned back on that damp sheet and closed my eyes to the cool cloth that nurse held while the doctor’s words floated right on by. I didn’t want to look at Everly; I didn’t want to hear that white baby cry.

“Why there’s a little albino,” that woman said and pointed in the nursery window. She shook her head sadly and I felt so ashamed for him. I turned my face away from their talking, stared at the row of orange plastic chairs there in front of the desk where just yesterday, Everly and I had stood so excited like we hadn’t already gone through it four times, my bag packed with the new robe and slippers, notes from my girls. Their whispers seemed to get louder.

“You mean that’s a BLACK baby?” the girl asked, her forehead wrinkled up. Then they looked at one another and laughed, the craziness of the notion that my snow white baby was black, and I couldn’t help but wish that their white baby would come out black as pitch. “Hey Gramma,” the girl said and gripped the woman’s arm, jumped around a little from side to side because the nurse was wheeling in a new baby. “How do you KNOW that’s a black baby? I mean either you’re black or white.”

“I know by how he looks.”

“He LOOKS white,” the girl said, her face going red when the woman grabbed her arm and shushed her. That girl kept staring at my baby, her forehead still wrinkled, until the nurse wheeled their baby right up next to mine. They had a girl baby, a pink ribbon taped to her slick bald head. They tapped on the glass and cooed, and I knew that woman’s sneakers were firmly planted there on the linoleum for hours. My baby stretched his little white arms and I imagined he thought they were there for him with all their oohs and ahhs and words of love.

“Who are you here to see?” The woman turned suddenly, her face flushed with pure raw happiness.

“That one,” I said and pointed to a dark brown baby girl in the far comer of the nursery.

Late that day, I looked out my window to the sidewalk that ran there in front of the hospital. My babies were all lined up in their Sunday School clothes, four little girls, ages ranging from nine to three, their hands held together like cutout paper dolls, their skin like gingerbread, glistening with the heat of summer, and in my mind there came to meet me that sweet soured smell of children who have run and played all day until their clean starched clothes are damp and limp.

Lolly, my oldest, held up a sign she had painted and the others scattered about like little squirrels on the grassy spot in front of her so they could see, too. I read “Mama” the letters all crayoned crooked, and I was making out the other words, “Miss” and “We” when the nurse tiptoed in from that bright hallway with him in her arms.

“You’ve got a hungry son,” she said, but I didn’t turn. I watched Sadie and Teena twirl like little pin wheels until drunk and wobbly; they flung themselves to the ground, arms stretched out rich brown upon the grass, mouths opened in laughter. I watched Scooter, my baby whose real name is Mary, undo a braid from her shiny black hair and fling the barrette at Everly who was sitting on a bench close by. Scooter is darker than the others; she is the same rich dark color of Everly. Scooter flung her arms in a wave, her hair all undone which is how she liked it, and I imagined Everly and Lolly trying to hold her down and braid her hair with her fighting every step of the way like a little wildcat. I waved to my babies, could almost hear Teena scream “watch this” before she placed her head upon the grass and kicked over a somersault that showed her lacy panties and landed her off to one side where the others were laughing.

“Have you thought of a name?” the nurse asked, and I shook my head while I watched Everly wave to me, shake his head while the girls lined up to leap frog, somersaults ending every leap except for Scooter who climbed onto Lolly’s back and just hung there like a cape. Everly was way down there but I knew the disappointment was still in his eyes. It was a look I couldn’t forget. It was the same look the girls had that one Christmas when Santa didn’t bring a thing asked for, and I felt so guilty and hopeless that I wanted to get on my knees and beg them to forgive me. But then they would have known, would’ve known the secret that their fat white Santa was nothing but me and Everly.

“Santa doesn’t always just work on Christmas day,’’ I told them later that night when they had abandoned the few new things and gone back to the television. “Santa knows a secret,” I said and rubbed my stomach where Scooter was nothing but a tiny dark ball. “We’re gonna have us a new baby, a brother or sister, come summertime.” I was halfway there; I had their attention. “And Santa Claus, he knows that Mona Robinson’s cat just had five baby kittens.” Now, they were all around me, Everly, too, because he hadn’t known about Scooter until that very minute. “Santa told me he wants you to have a kitten, too,” I said and watched them clap their hands and laugh; they were much more excited over a kitten than a baby, except for Everly, of course, who came over and hugged me so tight.

“If you bought that kitten in a store,” I heard Everly telling the girls. “It would cost a hundred dollars. Mona says it’s part Persian.” I was in the kitchen when they came in, one by one, the front door slamming and trapping all of the high-pitched squeals.

“He’s a Persian,” Lolly said and ran to me with that fluffy white ball. He was as white as my baby; white as snow, Everly said, and so Lolly named it Snoball like the snow at the North Pole, like the snow she’d never even see here in South Carolina. All night long, I kept hearing Lolly pad back and forth to the kitchen door where we had made Snoball a little cloth bed. “I can’t believe he’s mine,” she sighed the one time that I got up to check on her, all the others asleep, Everly’s snores as relaxed and even as Snoball purring. “A new baby will cost us,” he had said just before falling asleep. “But we can do it,” and I knew he had in his mind a son.

The nurse was still behind me, saying “there there” in response to his cries. I looked out the window, looked at my strong dark children and I knew how mama cats must feel when they kick that runt to the side and pretend it never was. Snoball was the pick of his litter, Mona had told the girls, and he grew up so fat and big. He grew into a regular old Tom cat, Persian or not, and took to roaming about and getting into fights until he got hit out there on Sampson Highway. Just remembering that gave me a sudden rush of fear that made me wish I could trap my babies right there, just as they were that second and keep them there forever.

“Who does he look like?” I turned suddenly with the voice, fast enough to see the nurse’s face aflame. I made her uncomfortable without meaning to; I couldn’t think of any words and before I could, she was talking so fast, telling me he’s so sweet, the best boy in the nursery. “He loves cuddling,” she said and held him up close, the same way Lolly had hugged that kitten. “He’s so sweet.” I wanted to say keep him, but no, I took my baby and held him, looked at him. He grabbed my dark finger and pulled it to his mouth.

“He looks like me, I think,” I told the nurse, who seemed to breathe out for the first time, her eyes watering as she smiled and nodded. “And his eyes, well, his eyes make me think of my mama.”

When the nurse left, I went back to the window just in time to see Everly and the girls turn off the sidewalk into the parking lot. I watched until Scooter who was the last in line, skipped around that comer and out of my sight. My baby acted like he was starving, those tiny white hands kneading my skin while he nursed. Who did my baby look like? I didn’t know. His eyes looked nothing like my mama’s; his eyes were so pale I felt like I could’ve seen through them if I had stared long enough.

Way back, before Everly got his job with the phone company, we both used to work at the restaurant of the Holiday Inn that’s north of town on the interstate. I waited tables and he bussed them. We weren’t married long and people knew it by the way we’d pass and touch one another’s hands or the way we’d wave across the dining room. One day I had a group of ladies who said they were just passing through, said that they were going on a vacation trip to Florida, that two were widowed and the other two had left their husbands way up in Maryland to take care of themselves for a week. I wanted to tell them something as well, so I pointed to Everly who was clearing a table and I said, “That’s my husband over there.” It made me feel so proud I had Everly, so young and alive, and that I had no wants to go anywhere without him.

“Why,” one of the women said, the one who had been driving all morning. “He looks just like Sidney Poitier.” I laughed and thanked her, knowing full well that the only similarity between my Everly and Sidney Poitier was their coloring. Everly and I laughed about it all that night; I called him Mr. Poitier and we fell out on the bed laughing. I laughed, but later, in my mind, I thought of all kinds of things I might have said to make them see that Everly looked nothing like Sidney Poitier. I could have said, “Yes, and I look just like Lena Home and Ethel Waters and all three of the Supremes. And you. You all four look just alike. I can’t tell you apart. I can’t remember who ordered chicken salad and who got the diet plate.” They would’ve frozen, white faces frozen like they had seen a ghost. I would have waited a few long minutes and then I would have said, “It’s because you’re white.”

I stared down at my baby, his skin so pale and thin next to mine. It made me think of those little summer frogs that Teena likes to catch, their bodies so clear looking, you can almost see bone. I pulled my baby closer to me, my arms like a strong wall around his little body, and told him I was so sorry that he had turned out that way. I told him I didn’t know of anybody that he looked like. He drew in close to me because he didn’t know; he didn’t know a thing but that I was his mama. I wished he never did have to know.

My baby closed his eyes and slept there in my arms for the longest time. There was something about the spacing of those little sleepy eyes that made me think of Everly. I told him we were gonna do just fine. He was sweet, a good baby like they had all said, and when the nurse came to get him, he didn’t want to leave. He cried when he was pulled away from the warm spot I had made for him in my arms. “His name is Everly Bennett Winston Jr.,” I told the nurse before I had time to think, before I had time to shape in my mind a picture of Everly holding a photo of his namesake for all the people at the phone company to see, his hand curled into a hard dark fist that dared anyone to speak.

It was hot the next day when Everly came to get us; Mona Robinson was at our house with the girls. I wrapped Bennett in a blanket, careful so that bright sun wouldn’t get in his eyes. Everly said he had the crib all fixed and ready, that the girls were so excited, that Scooter had tried to put dollbaby clothes on that new cat and got her hand scratched. He said Mona had brought over enough food to keep us eating for a week or better, that Mona said she planned to wait on me hand and foot. He didn’t say if he had told them what my baby looked like and I didn’t ask. I knew by the look on Mona’s face that he hadn’t. She stood there with a big red balloon and I watched her laughing face go quiet. “He’s white,” Lolly said and looked up at me, her little forehead more wrinkled than that girl’s at the hospital. “Oh, but isn’t he sweet?” Mona asked and stepped toward me like she had just snapped from a spell. Mona took Bennett and she kissed his little cheek and pulled him into her chest. “He’s fine,” she whispered and looked at me, her eyes like she might cry and for what reason, I wondered, happy or sorry; I couldn’t stand to ask her.

Scooter took to Bennett right off; I’d find her little barrettes, like gifts, left there by the crib where she had sat and watched him. Scooter didn’t notice any difference until the others pointed it out to her. One by one, they all came to me to ask WHY and I explained the best way I could. I said Bennett was special and hated myself for saying it when what I really meant was different. I stayed in the house with that baby for two months. I might have stayed locked in forever if Everly hadn’t talked me into getting out, talked me into taking the baby out. I went to the grocery store and I knew people were staring at me with my snow white baby. I finally stopped, right there in the meat department, and turned to face the woman who was looking at me. I looked at her, stared at her until she stopped staring at us and went back to her shopping. “You did right,” Mona told me later while she sat on my porch and rocked Bennett. I was braiding Scooter’s hair in perfect plaits around her head even though I knew she’d undo them the first chance she got. “I don’t want him to ever feel ashamed,” Mona said, and for the first time in all these years of me knowing her, I got so mad. It was like she was Bennett’s mama; it was like she was calling me ashamed. I pushed Scooter away from me, told her I was tired of plaiting and for her to go on and play, take those braids out. I waited while Scooter ran down the road where some others were playing, waited to see if Mona was going to put in another two cents worth.

“You don’t know what it’s like to be ashamed,” I told her. “You don’t know.”

“No.” Mona stared down at my baby and shook her head. I tried to calm myself down, but the longer Mona sat there like that with my baby held so close, the madder I felt. I was just on the verge of grabbing Bennett and telling her never to touch him again, when she looked up at me. “I have no idea,” she whispered and all my anger fell right off. Mona loved my babies like they were her own; Mona had told me once that she’d give anything to have one of her own. Something inside her body was not right. “But I love Bennett,” she continued. “I love him and I don’t want anybody ever leaving him feeling like he doesn’t deserve that.” I sat down in the rocker beside her and leaned my head into hers; I said, “What would I do without you?” and I watched my Scooter way down the road where she was skipping a rope, her hair bushing out in little twists. “If you didn’t have me,” Mona said, her voice nothing more than a crackly whisper, head pressing in closer to mine, “you’d have to hire a maid.” We laughed, laughed until we couldn’t stop, laughed until Bennett woke up and started crying and Lolly and Teena came out to see what was funny. Mona and I had both done some work as domestics; it seemed that was water long gone under the bridge.

Bennett learned to crawl even faster than Scooter did. I’d be in the kitchen and in no time at all, he’d make his way from that living room rug in there to my feet. One day I heard Teena calling him in a little singsong voice like you might use to call a cat. “Here Whitey,” she said and I froze there in the doorway, so much on the tip of my tongue, when I saw Bennett make his way over and curl in her arms, responding to the sweetness I had mistaken for something else.

Sometimes at night I can’t sleep for thinking of all we have ahead of us. One night I dreamed that Bennett was a grown man, far off in college where everybody thought he was white. I got a letter that said he was getting married, that she was white and didn’t know about any of us down here in South Carolina. He said he couldn’t come home anymore, that it would ruin his life. He said that he told that girl he didn’t have any family, and somehow, when I thought of Bennett in that dream, he had eyes just like my mama. I woke myself up crying; I had to get up, leave Everly there in the bed, and tiptoe into the living room to make sure the crib was still there, that my baby was still in it.

Everly tells me that we can’t ask why, can’t know why, but sometimes I do ask, can’t help but ask, and if I think on it all too long, I feel my body get hard all over. Bennett is almost two now and I know it won’t be much longer until he starts to ask ME why. Just last week, I heard a boy from down the road talking to Teena. They were on the porch and I had the windows open. Bennett had fallen asleep right there on the floor, tired from running around in the yard where I had been working. He smelled like that sunning screen that I had rubbed him down with. “I’ll pay a quarter to see that albino,” I heard that boy say and I don’t even know what Teena answered or if she did at all, because I flew out that front door with all the energy that I have held in all this time. That child backed off, stumbling on the bottom step, and I grabbed his arms so tight I could’ve snapped them off. I pushed him up against a tree and shook him; I shook him for all he was worth, the tears rolling down his face and that only made me madder, only made me want to shake him harder. I heard Teena screaming but I don’t know what she said, or what I said; all I know is that I held those lean brown arms of his and shook him until Mona came and pulled me away from him. He backed off slowly, eyes so wide, while I squatted there in the yard and tried to hide the sobs that were coming from my mouth. Teena stood way off on the porch, Scooter hugged up close to her like they were afraid of me. Lolly and Sadie were peeking around the corner of the house that same way.

“You crazy woman,” that boy called when he was half a block away. “I’ll tell my mama what you done to me.”

“You tell her,” I whispered while Mona knelt there beside me, hugged. I’LL TELL MY MAMA. I imagined Bennett saying that his whole childhood; I imagined big dark boys waiting for Bennett behind the schoolhouse, on the schoolbus. I imagined them pinning his thin white arms and shaking him until the tears came from those clear pale eyes. “I don’t know why I did that,” I told Mona and sat back in the dirt, but I did know. I know that I was shaking that boy for what he had said, but I also know that I shook him for everything that is ahead of us, all of the times when I’ll want to shake somebody and not have the power to do it.

Everly keeps telling me that we can’t think about it all at one time. “We got to take things as they come,” he says. “We can’t do it all for him. Bennett’s gonna have to leam to take care of himself one day.” Everly tells me that I’ve got to have faith, that if I keep Bennett from doing things like other children, then I’ll be the one that makes him feel different. Still, I can’t help but think of things that might happen. I can’t help but think of the fighting Everly and I might do over whether or not to let Bennett do something. I can’t help but think that the girls could grow up to be ashamed of him, that he might never have a friend, get invited to a party, have a date, marry, have somebody other than us and Mona that loves him. I have to think about what I’m gonna do.

I watch Bennett now, laughing while he follows an old tabby cat, and I can’t help but hate myself for the way I felt the first time I saw him there against the doctor’s coat, the way I spent that whole first year wishing that I’d get up one morning and find him browned overnight. I hate myself for ever feeling that I didn’t want him, for overlooking him and lying when I said that other baby in the nursery was mine. I love my girls; I love them to death, but the way I love Bennett is bigger than anything I can understand. “We can’t give Bennett all the love and attention,” Everly tells me. “We’ve got the girls to think of, too.” And, I know he’s right, but when I watch my girls so brown and healthy, skipping right into a crowd of other children, I can’t help but give Bennett all the extra. Maybe cats have a way of knowing if they kept that one so much weaker and smaller than the others, that they couldn’t help but give it the most time and loving; maybe they know that they would fuss and worry over that one for a lifetime. Maybe they see in that one all the weakness and shame of themselves.

When Bennett turns five, we are going to have the biggest birthday party that this side of town has ever seen. We are going to have silver balloons and a clown and so many ice-cream cakes you can’t count, and we’ll only invite the children that have been nice; the others will stand down the road a piece and watch and feel sorry that they’ve acted ugly. And he will get to and from school with no trouble if I have to get on that bus and ride it myself. I will take him down to the dime store when Olan Mills sets up, and I’ll get a nice portrait made; I’ll get enough wallet-sized photos to give to everybody in town. I’ll say, “Who do you think he looks like, me or Everly?” And every day that passes, every day that he moves further down the road to play, to go to school, I’ll be right there on the porch waiting for him, never knowing what to expect, and with every word, every time my arms pull him in to where he’s safe, I will have to wonder on all that Everly says. Am I doing him right or doing him wrong.

Now, he reaches toward the floor fan, those blades whirring, casting shadows on his small white hand. “No baby.” I say and pull him away as I’ve done a hundred times before. He smiles at me and then as soon as I turn my head, he goes right back again.

Tags

Jill McCorkle

Jill McCorkle is a native of Lumberton, North Carolina. She is the author of Tending to Virginia (Algonquin Press, 1987.) (1988)