The War at Home

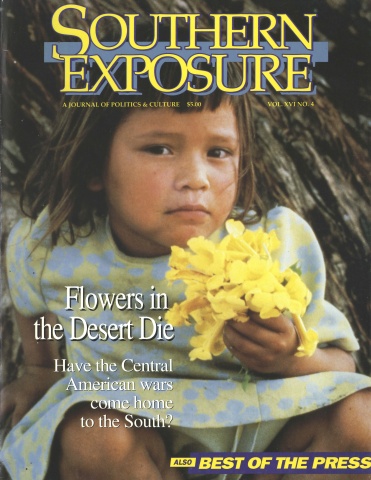

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 4, "Flowers in the Desert Die." Find more from that issue here.

The memo to the Pentagon was signed by the director of the Office of Public Diplomacy, the key federal bureau in charge of “educating” the American public on U.S. policy in Central America and the U.S. war on Nicaragua.

Dated March 5, 1985, the memo stated that the office was conducting “projects of a priority nature” that “require the expertise available from personnel of the 4th Psychological Operations Group, Fort Bragg, North Carolina.”

Within three months, five “psy-ops” specialists from Fort Bragg were headed for Washington, D.C. The five men were soldiers trained in psychological warfare — experts at identifying cultural and political weaknesses that can be used to manipulate the populations of foreign countries.

This time, though, their target was not a foreign country. This time, their target was the American people. The U.S. government was waging what one official called “a huge psychological operation” against its own citizens to convince them to support the Nicaraguan contras — and in this war, many of the battles would be fought in the South.

Around the Office of Public Diplomacy, an obscure bureau in the State Department that went by the even more obscure acronym S/LPD, the Fort Bragg specialists were referred to as the “A-Team.” As a deputy in the office informed his boss in a memo dated May 30, “We have enough to keep them busy until the contras march into Managua.”

The specialists were kept busy analyzing classified cables and designing glossy government publications that portrayed the Sandinista government as a Soviet-sponsored menace, and the contras as “freedom fighters.” Among their duties, according to a memo prepared by Lt. Colonel Daniel Jacobowitz, another “psy-ops” specialist, was to look “for exploitable themes and trends, and . . . inform us of possible areas for our exploitation.”

Target: The South

Why were U.S. psychological warfare personnel engaged in the “exploitation” of the American public? The answer is part of a larger story of how the Reagan administration ran what a staff report of the House Foreign Affairs Committee called “a domestic covert operation designed to lobby the Congress, manipulate the media, and influence public opinion.”

Although the story of how the White House set up a veritable propaganda ministry within the executive branch has slowly begun to emerge, part of the story that remains largely untold is how the South played a pivotal role in this secret “public diplomacy” campaign.

The region was a target for two reasons. First, it was in the South, according to political strategists working with Lt. Colonel Oliver North, that conservative “swing vote” Democrats were most vulnerable to pressure to support contra aid. Congress had cut off all CIA military assistance to the contras in 1984; if the Administration was going to win back contra aid, the margin of victory would likely come from the votes of congressional representatives in Georgia, North Carolina, Kentucky, Florida, and Texas.

Second, private sector groups working closely with the White House needed millions of dollars to lobby these Southern swing votes, and some of the richest conservative donors willing to foot the bill hailed from Southern states. Thus, although the ultimate target of the Reagan administration’s “public diplomacy” operations was Capitol Hill, the South became the key zone of operation.

The War of Ideas

The genesis of the public diplomacy operation dates back to January 1983, when President Reagan signed National Security Decision Directive 77 entitled, “Management of Public Diplomacy Relative to National Security.” This directive authorized the creation of a centralized bureaucracy in the National Security Council (NSC), dedicated to waging the “war of ideas” on issues like Central America, nuclear arms, and Afghanistan.

That same month, on January 25, CIA propaganda veteran Walter Raymond Jr. wrote a ‘Top Secret” memo hailing public diplomacy as “a new art form” and arguing that “it is essential that a serious and deep commitment of talent and time be dedicated to this.”

From documents and depositions released during the Iran-contra investigation, Raymond emerges as the key bureaucrat in the public diplomacy apparatus. Transferred to the NSC in 1982 by CIA Director William Casey, Raymond chaired a Central America public diplomacy task force which met Thursday mornings in his office at the Old Executive Office Building next to the White House. Lt. Colonel North attended some of these meetings, as did representatives of the CIA, the Departments of Defense and State, and the U.S. Information Agency.

There was no question about who they answered to. In a memo to Casey, Raymond reported that the task force “takes its policy guidance from the Central American RIG.” By RIG, he meant the Restricted Interagency Group made up of Oliver North, Assistant Secretary of State Elliott Abrams, and CIA operative Allan Fiers — the same men who were overseeing the covert operations to secretly funnel weapons to the contras.

Raymond was also the driving force behind the creation of the Office of Public Diplomacy and the appointment of Otto Reich, an anti-Castro Cuban American and former city administrator in Miami, to be its director. Although the S/LPD office was located in the State Department, it reported directly to North and others at the National Security Council.

On the surface, the office functioned as a ministry of information, churning out vituperative “white papers,” sending officials around the country to speak to civic groups, paying prominent Nicaraguan exiles to write anti-Sandinista diatribes. Behind the scenes, however, S/LPD engaged in a number of dubious, if not illegal practices. Besides using “psy-ops” personnel to look for “exploitable” themes, the office manipulated news coverage of Central America by selectively leaking classified information to favored journalists. It also planted opinion pieces known as “white propaganda” — articles written by people on the federal payroll, but published under the names of scholars or contra leaders.

From Motor Lodge to Condo Land

Since the law forbids U.S. government officials from direct lobbying, the Office of Public Diplomacy turned to private sector groups to raise money and lobby the Southern swing votes in Congress. As early as August 1983, William Casey called together a group of corporate public relations specialists to discuss how to “market the issue” of Central America and promote a “public-private relationship” to generate funds.

The office also used taxpayer money to employ public relations firms to conduct lobbying and propaganda. According to a March 17, 1987 staff report prepared for U.S. Representative Dante Fascell (D-Florida), S/LPD “was paying one or more outside contractors to conduct ‘public diplomacy’ aimed at influencing the Congress” and had entered into “secret contractual arrangements which might violate prohibitions against lobbying and disseminating government information for publicity and propaganda purposes.”

The main contractor for S/LPD was International Business Communications (IBC), a public relations firm in Washington, D.C. run by former government officials Richard Miller and Frank Gomez. Between 1984 and 1986, IBC received seven contracts totaling over $440,000, including one $276,000 contract classified “secret” to do contra media work — write briefing reports, create mailing lists, hold press conferences, and take the contras on a national speaking tour.

IBC, in turn, worked closely with a tax-exempt, ostensibly non-profit organization called the National Endowment for the Preservation of Liberty (NEPL) run by conservative fundraiser Carl “Spitz” Channell. Channell grew up in Elkins, West Virginia, where he managed the family-owned motor lodge before heading for Capitol Hill in 1979. He quickly rose from obscurity as a protege of the late conservative tactician and fundraiser Terry Dolan to control an empire of nine anti-communist foundations and political action committees.

There was lots of money to be made in helping the contras. By 1986, Channell reported a gross worth of $1.4 million. He dined at Washington’s finest restaurants, drove a $20,000 Lincoln Town Car (when he wasn’t being chauffeured in a limo), and lived with his lover in a $300,000 condominium.

Battle of the Airwaves

In late 1985 and the spring and summer of 1986, Channell and Richard Miller spent more than $1.5 million on political ads and lobbying designed to pressure Congress to aid the contras. The South was a particular target of the political campaign. In one lobbying strategy paper put together for Channell, Terry Dolan wrote:

I do agree that special attention should be paid to the South for three reasons:

1) These congressmen are generally more conservative.

2) The South will bear most of the burden of a refugee problem.

3) A shockingly high number of these Southern conservatives voted wrong.

Thus, Channell and Miller put together a sophisticated and well-financed lobbying/public relations campaign aimed mostly at the South. A program of television ads and contra speaking tours, dubbed the Central American Freedom Program, was put together in February 1986. NEPL paid $110,000 for extensive polling to guide where the ads and tours would have the most impact on the “swing voters.”

“Freedom Fighters TV” was the centerpiece of the Central American Freedom Program. Channell poured over $1 million into the anti-Sandinista, pro-contra commercials, which were produced and placed by the Baltimore-based Robert Goodman Agency.

“Our strategy is to target those Congressmen who, by virtue of their record on Nicaragua, seemingly have yet to make up their mind,” Goodman wrote in a planning report prepared for Channell on December 9, 1985. “This national spot program is a pioneer attempt to effectively influence public opinion as prelude to a critical congressional debate and vote.”

Lt. Colonel North provided some of the footage of Soviet-built Hind helicopters for the political commercials. Miller and Channell even took prototypes of the ads to show Assistant Secretary of State Elliott Abrams, who said he thought they were “pretty good.” When Abrams testified before the Iran-contra committees, the following exchange took place with Representative Fascell:

Fascell: Did you know Mr. Miller and Mr. Channell were targeting congressional districts for ad campaigns designed to influence targeted congressmen on aid to the contras?

Abrams: They told me, as I recall, that they were targeting kind of the Sun Belt.

Fascell: That is me, I am the Sun Belt.

The pro-contra commercials ran in congressional swing districts for eight weeks in February and March before an initial vote on the president’s request for $100 million in contra aid. In March, another Goodman report on the ads congratulated Channell on his success. “NEPL’s national television campaign achieved one more important thing: it influenced votes.” Goodman wrote:

For example, NEPL advertised in four of Florida’s biggest television markets, covering the home districts of16 Congressmen. On the final House vote on Contra funding in late March, 14 of the 16 Congressmen sided with the President in support of the Freedom Fighters. This is dramatic considering many of these Congressmen were considered to be on the “swing vote” list. . . . The results were even more impressive in markets like Jackson (MS) and Savannah (GA) where our success rate on the final vote tally hit 100%!

Contra speaking tours, directed by IBC and Richard Miller, accompanied the barrage of television commercials: Channell spent some $600,000 taking contra leaders to swing districts. An NEPL press statement in February 1986 reported, “In November [ 1985], NEPL launched a series of speaking and media tours reaching 36 cities throughout the Southeastern United States. By the end of February, the tours will have reached 18 of these cities twice. To date, they have reached an audience of 32 million.”

Finally, in the last eight days before the congressional vote on contra aid in June 1986, Channell announced that his organization would launch one last-ditch blitz of television ads. This campaign cost $200,000 and focused exclusively on 10 congressmen in Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Texas.

On June 23, 1986, Congress passed Reagan’s $100 million contra aid package by a narrow margin. Public diplomacy operatives inside the government and out trumpeted their success. “It is clear we would not have won the House vote without the painstaking deliberative effort undertaken by many people in the government and outside,” Walter Raymond exulted in an August 7, 1986 secret memo prepared for CIA Director Casey. On November 11, only two weeks before the sale of arms to Iran and the diversion of funds to the contras was uncovered, Oliver North awarded Spitz Channell a “freedom fighter” commendation from the president.

The Wright Stuff

But the contra lobby campaign didn’t end with the congressional vote. Throughout the fall, Channell’s network of organizations spent thousands of dollars on negative and derogatory ads in a thinly veiled — and patently illegal — effort to defeat Democratic candidates who had voted against contra aid.

“By its own admission, NEPL targeted its contra advertising primarily against Democratic candidates in Southern states, including, for example, Ed Jones in Tennessee, J.J. Pickle in Texas, and W.G. Hefner in North Carolina,” the Democratic Congressional Campaign charged in a complaint filed with the Federal Election Commission last April. “The evidence is clear that NEPL worked . . . to influence the outcome of congressional elections in 1986 — against Democratic candidates.”

Although no congressmen were defeated by this campaign, a number expressed outrage at the tactics used against them. “I have to assume that the White House and White House officials knew these ads were going to be run,” Representative Pickle said.

NEPL also had plans to target incoming Speaker of the House Jim Wright (D-Texas), who had voted against contra aid. In 1985, Channell commissioned a comprehensive 37-page lobbying “action plan” on Wright’s 12th congressional district in Fort Worth, Texas. The plan laid out a grassroots political campaign strategy to pressure Wright through the mobilization of local conservatives and the use of direct mail drives, “freedom petitions,” and the media.

“Wright’s vote against military aid to the freedom fighters is not ideological, but pragmatic,” stated the report, which was prepared by the Edelman Public Relations firm in Washington, D.C. “Were he not a member of the Democratic leadership with ambitions for the Speakership, he may very well have voted for aid, at least non-military aid. Because of his ambitions, it is unlikely he will change his vote. . . . However, an effective campaign by NEPL in his district may force Wright to revisit the issue and keep an open mind . . . the district campaign will, at the least, attempt to neutralize Wright’s active opposition to military aid to the contras.”

Blue-Rinse Brigade

To raise the millions of dollars needed to pay for this extensive propaganda and lobbying campaign, Channell again turned to the South. His fundraising strategy was simple: target conservatives — particularly elderly wealthy widows known as the “blue-rinse brigade” — and use access to the White House as bait for donors.

Much of his fundraising took place in the South. Two of his largest donors, for example, lived in Austin, Texas: Ellen Garwood, who provided over $2 million, and Mae Doherty King, who readily gave Channell almost $1 million. Donors who could give from $20,000 to $200,000 were brought to the White House for a private briefing with Lt. Colonel North, who showed them his slide show and gave them his standard speech about how the contras were suffering at the hands of the Soviet-supplied Sandinistas. Those donors who could give $300,000 or more were treated to a private session with President Reagan himself. Thus, Channell essentially sold tickets to the White House as a means of raising millions of dollars for a propaganda and lobbying campaign.

North’s personal calendars released by investigators indicate that he met with Miller 49 times in 1985 and 1986 to discuss raising money for arms and “approved PR programs.” Although North testified under oath before the Iran-contra committees that “I do not recall ever asking a single, solitary American citizen for money,” he did write fundraising appeals on NSC stationery to over 30 of Channell’s biggest contributors. Many of these letters were addressed to wealthy Southern Republicans in Texas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Florida, and Georgia.

“During 1985, the hope of freedom and democracy in Nicaragua was kept alive with the help of the National Endowment for the Preservation of Liberty and fine Americans such as you,” North wrote in a January 1986 pitch to Mrs. Barbara Bullitt Christian of Prospect, Kentucky. “In the weeks ahead, we will commence a renewed effort to make our assistance to the Democratic Resistance Forces even more effective. Once again your support will be essential.”

North sent an identical letter to Nelson Bunker Hunt, the Texas billionaire. To solicit Hunt, Channell arranged a private plane to fly North to Texas for a dinner meeting in September 1985. In a scene right out of the TV program Dallas, the three men ate at the Petroleum Club and discussed the contras’ need for $5 million in equipment. The final report issued by the Iran-contra investigators describes the scene:

North gave his standard briefing, without slides, and showed Hunt a list of various contra needs. The list was divided about evenly between lethal and non-lethal items, and included . . . aircraft and a grenade launcher. . . .The total price was about $5 million. According to Channell, after discussing the items on the list and their prices, North “made the statement that he could not ask for funds himself but contributions could be made to NEPL. . . . North then left the room, a maneuver that had been ‘pre-arranged.’”

As a result of this dinner, Hunt made two payments to NEPL of $237,500 each.

In 1985 and 1986, Channell raised a total of $10 million. Approximately half of the money — $5 million — went to pay salaries and expenses for IBC and NEPL officials. Roughly $2.7 million was transferred through IBC to North’s secret bank account in Geneva to purchase contra weapons; another $500,000 was paid to other individuals helping the contras. Most of the remaining money was used to pay for political ads and lobbying.

When the Iran-contra operations were exposed in November 1986, so too was the link between the National Security Council, the Office of Public Diplomacy, IBC, and NEPL. For their role in collaborating with Lt. Colonel North to raise money for contra weapons, Richard Miller and Spitz Channell became the first actors in the scandal to be brought to justice. (In the spring of 1987, both plead guilty to defrauding the U.S. Treasury.) In December 1987, Congress quietly closed down the Office of Public Diplomacy for its questionable “white propaganda” operations and its contract with IBC.

The State Department’s inspector general has put the equivalent of a letter of reprimand in the personnel file of former S/LPD director Otto Reich, now ambassador to Venezuela.

But the larger issue of how the Reagan administration got away with using CIA propaganda specialists, psychological warfare personnel, and private-sector conduits in an effort to distort and stifle full democratic debate remains unexamined. As Thomas Jefferson once said, “Only an informed democracy will act in a responsible manner.” Unless the American public demands its constitutional right to be truthfully informed, there is nothing to prevent this type of abuse from happening again.

Tags

Peter Kornbluh

Peter Kornbluh is an analyst with the National Security Archive in Washington, D.C. The views expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Archive. This article was supported by the Investigative Journalism Fund of the Institute for Southern Studies.