This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 4, "Flowers in the Desert Die." Find more from that issue here.

Harlingen, Texas — Three young boys slump on the couch in the makeshift waiting room of Proyecto Libertad, a nonprofit legal aid group for Central American refugees. Jose Erick, Jose Sarvelio, and Napoleon, exhausted from the thousand-mile journey from their home in El Salvador, have just enough energy left to annoy their uncles with questions of when they will be able to join relatives in Canada.

Near the water cooler sits Ovidio, a 31-year-old campesino from the war-battered province of San Miguel, El Salvador. His tattered suitcase rests on his lap, and his wet pants legs attest to his early morning arrival from el otro lado — the other side.

Next to him is Angela, who is nursing her baby. She and her family left Guatemala a few weeks ago, crossing Mexico by bus and the Rio Grande River on foot. The group was arrested and turned back by the U.S. Border Patrol when they attempted to pass a military-style checkpoint in a Greyhound bus headed for Houston.

These refugees — and thousands of others from Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua — have come to the United States seeking refuge from war and hunger. What they have found instead is a government determined to trap them at the Texas border, turn local residents against them, and literally starve them back to Central America.

Angela, Ovidio, and the other families crowding Proyecto Libertad’s office in Harlingen have been forbidden to leave the area unless they post a $3,000 bond per person. They have no jobs, nowhere to live, and no way to raise the money to buy their freedom. They will spend the coming months battling the federal bureaucracy, trying to join their families and put their lives back together.

The reason for such harassment, say refugee advocates in Texas, is political. Most of the refugees are eyewitnesses to the horrors of U.S. foreign policy in Central America. Many offer direct testimony of murder, torture, and hunger, yet they are forced to seek refuge in the same country that has trained and armed soldiers to kill their families and friends back home.

The U.S. government is detaining Central American refugees in the South because it “had to stop people from leaving,” says Lisa Brodyaga, founder of Proyecto Libertad. “What they don’t want is legal people running around addressing North Americans about foreign policy without the fear of being arrested.”

Welcome to America

Most Central American refugees enter El Norte through the South, crossing the U.S. border into the Rio Grande Valley. The land here exists in a quiet state of siege, under constant surveillance by Border Patrol agents of la Migra — Immigration and Naturalization Services. The patrol uses radar, helicopters, sophisticated night binoculars, local informants, and a three-ton military land rover known as the “Hummer” to police the Valley and arrest anyone crossing the border without permission.

More important, though, the agency has taken advantage of the Valley’s geographic isolation and devastating poverty to enforce bond and detention policies that make the area the toughest place along the border for refugees to seek asylum.

Harlingen is the only INS district in the country that prohibits refugees from continuing their journey north without paying a bond of $3,000 or more, effectively turning the entire Valley into a de facto detention camp. With the Gulf of Mexico to the east and the Mexican border running diagonally to the west, the Valley is cut off from the rest of the country like a slice of pie. Only two highways lead north, and both are heavily guarded by Border Patrol agents. At the top of the Valley sits the huge King Ranch, its miles of rough terrain deterring almost anyone who tries to skirt INS checkpoints on foot.

At any given moment, several thousand refugees are detained in the Valley, jobless and homeless, awaiting asylum hearings. Another 400 to 500 are held on bonds as high as $10,000 in el corralon — the big corral, the nation’s largest INS detention center located 30 miles from Harlingen.

Despite the obstacles to asylum, U.S .-sponsored wars and unrelenting poverty continue to flood the Valley with refugees. In the last five years, Border Patrol agents have arrested more than 50,000 Latin Americans, not counting Mexicans. Officials estimate that another 100,000 have slipped through undetected, and some observers put the figure at more than 200,000.

Such numbers are startling, particularly when compared to the population of Central America. Today there are nearly one million Salvadorans in the U.S. — more than one-tenth of the population of El Salvador. Each year, those refugees send back more money to their families than their entire country produces in a year. Nicaraguans in the U.S. number roughly 225,000, with an average of 250 new arrivals each week. The Guatemalan refugee population has now reached 160,000.

It’s a Job

Entering the Valley, refugees find a poverty far removed from their image of American wealth. The seven-county area has been dubbed “the new Appalachia.” It is the poorest region in the nation, with per capita income of $6,000 and unemployment as high as 50 per cent in the rural slums known as las colonias.

One of the better-paying and more popular jobs around is as a Border Patrol agent. Local Mexican-American residents, desperate for work, line up for jobs as border cops, even though it may mean deporting a friend or relative.

Even the chief of the Border Patrol is Hispanic. Silvestre Reyes, a native of El Paso, seems to be on the local news every other night calling the bedraggled refugees “illegal aliens” and saying they pose a threat to “national security.”

“We’re facing a multifaceted problem in terms of controlling our border,” Reyes says. “There’s an increase in alien smuggling, narcotics trade, and arms smuggling. The border today is one of the most dangerous areas in the country.”

Reyes and INS District Director Omer “Jerry” Sewell hit heavy on the “economic refugee” theme, telling local residents that Central Americans have come to take away their jobs. In late July, for example, the INS started a hotline so local residents could report employers believed to be hiring undocumented workers. Both of the TV stations in the Valley interviewed the crew-cutted Sewell about the hotline as he sat behind his desk, a huge Statue of Liberty adorning one comer. One station then cut to “Yolanda,” a local resident who blamed her joblessness on refugees who work for less than minimum wage. The other station switched to a shot of two local residents standing outside the unemployment office.

“There’s not enough work for everybody,” explains Jesus Moya, leader of the International Union of Agricultural and Industrial Workers. “The farmworkers feel Central Americans are taking their jobs. But it’s only because they are misinformed. You can count on one hand the number of Central Americans working agriculture down here.”

In reality, the INS itself has created and fueled the tension between residents and refugees. After all, the only reason Central Americans have been forced to seek work in the Valley over the last three years is because the INS has forbidden them to leave the area without posting exorbitant bonds.

Sewell says the bonds are an effort to reduce the number of refugees who fail to show up for their deportation hearings. But Linda Yanez, a Brownsville immigration attorney, calls the bond policy an “orchestrated attempt to turn locals against the refugees.”

No Way Out

Some refugees, unable to find work and post bond, pay human smugglers known as “coyotes” to get them to Houston. Daysi Hernandez got by the checkpoint on a bus in 1986 during one of the rare moments it was closed. The 29-year-old Salvadoran worked as a housekeeper in Houston, supporting herself and sending money to her husband and child in San Miguel. One day, she received a telegram saying her daughter was sick with the measles.

Daysi returned home immediately. “In my country, many children die from measles,” she explained. “I was very worried because my only other child, a son, died in 1980 from parasites and malnutrition. He was in the hospital in San Miguel getting oxygen when the power went out and he died. His stomach was full of blood.”

After her daughter recovered, the entire family returned to Texas to escape the U.S.-financed bombings in San Miguel. This time, however, the Border Patrol arrested the family shortly after they crossed the river and forbid them to leave unless they each paid a $3,000 bond. Daysi and her family were prisoners of the Valley.

Destitute, the family wandered the streets of Brownsville for 10 days, begging money and sleeping in the street until a sympathetic local minister saw them and directed them to Proyecto Libertad. There they learned about Refugio del Rio Grande, a refugee camp started by Brodyaga about eight miles from Harlingen. [See sidebar.]

Told their asylum would take months to settle, Daysi’s husband evaded the checkpoint and headed for Los Angeles to look for work. Daysi and her daughter boarded a bus for Houston.

“When we got to the checkpoint, I was asleep with the child in my arms,” Daysi said. “A Border Patrol officer came on the bus and pinched me to wake me. He was a tall, white Anglo. He pinched me so hard, it cut me on the knuckle of my little finger. He told me to wake up and to get down off the bus. I didn’t want to; I was desperate. I felt I had to get out of the Valley.”

The Border Patrol returned Daysi and her daughter to Brownsville, where they stayed with friends and looked for a job. “First one friend, then another, until I find work,” Daysi said. “Someone will hire me soon, don’t you think?”

A House Divided

The three private refugee shelters in the Valley no longer have room for all the refugees like Daysi. Together, the shelters hold no more than 450 — and the growing number of refugees on the streets only increases the tension between native Southerners and newcomers.

“The more people roam around, the more local people say, ‘There are all those refugees stealing and vandalizing,’” says Father Lenny DePasquale, until recently the refugee chaplain for the local Catholic diocese. “It contributes to the mistrust local people have for refugees.”

The diocese runs Casa Oscar Romero, a refugee shelter that made national headlines in 1984 when federal agents arrested its director and a volunteer for helping Central American refugees leave the Valley. But despite the negative publicity, neighbors didn’t begin complaining about the shelter until the new bond policy went into effect, causing extreme overcrowding and prompting fears of vandalism.

Sensationalized press accounts and self-serving politicians fueled the dispute in the neighborhood until the entire town turned on Casa Romero. Pressured by the community and overwhelmed by more than 500 refugees at a facility built to hold one-tenth that number, diocese officials closed the shelter and left the homeless refugees on the steps of the INS office in Harlingen. The INS promptly imprisoned 200 refugees at its detention center.

The INS couldn’t have asked for a better media event if it had planned one itself. Today, many local residents still associate the word “refugee” with Casa Romero. When the diocese opened a new Casa outside Brownsville in 1987, a citizens group calling itself “United We Stand” distributed anti-Casa bumper stickers, sued the diocese for sheltering refugees, and erected a 30-foot, three-tiered surveillance tower in a vacant lot behind Casa to watch for “subversive movements.”

The orchestrated opposition had a serious side effect — it squelched the shelter’s outspoken criticism of U.S. foreign policy in Central America. The diocese put a group of apolitical nuns in charge of the house and emphasized the humanitarian aspect of the shelter. The new philosophy seems to have mollified residents. Neighbors now express quiet support for the Casa; about 250 attended an opening mass last year. United We Stand, after its headline-grabbing debut, faded into an occasional letter to the editor.

Project Liberty

Perched on a wobbly stool behind a desk overflowing with files of refugee clients, Proyecto Libertad paralegal Jim Cushman answers the phone for perhaps the hundredth time today. “Con quien desea hablar?” he asks. “With whom do you wish to speak?”

Jaime, as the 33-year-old is known to the refugees, says many are forced to return to war and hunger in Central America because the new immigration law passed in 1986 makes it tougher for them to find work and post bond. Cushman estimates that as many as half of Proyecto’s clients eventually accept deportation even if they have strong asylum claims rather than face months behind bars.

Cushman has spent his six years as a paralegal documenting abuses by guards at the INS detention center known as el corralon. A folder he keeps in the office bulges with dozens of affidavits in which refugees attest to being verbally, physically, and mentally abused by guards.

Included is the case of Jesus de la Paz Andrade, a 29-year-old Salvadoran detained in January 1986. Peace workers touring the detention center discovered de la Paz in the infirmary, moaning and breathing heavily. Asked if a doctor had examined the refugee, a guard claimed de la Paz’s only problem was that “he hyperventilates and likes attention.”

Eventually, Cushman was able to obtain medical records which showed de la Paz was suffering severe kidney failure complicated by his journey on foot through Mexico, where he ate and drank almost nothing. Proyecto convinced the INS to reduce his bond to $1,000, raised money to pay for his release, accompanied him to Houston, and helped him get on a kidney dialysis program.

De la Paz lived with a cousin in Houston, barely getting by. Earlier this year, he was hit by a car and killed on his way for dialysis.

Case Closed

On the sixth floor of the First Republic Bank building, the tallest in Harlingen, Judge Howard Achtsam prepares to dispense his form of justice. The sterile hearing room is empty except for Proyecto lawyer Steve Jahn, INS attorney Grace Garza, a handful of Proyecto workers and friends, and the two refugees whose futures are at stake today — Maria and Antonio (not their real names), a young Salvadoran couple seeking political asylum.

Proyecto fights a losing battle at such hearings. Of the hundreds of asylum claims the center has filed for Central Americans in eight years, it has won only four. But Jahn is hopeful today; Antonio has perhaps the best case he has ever prepared.

Antonio, 29, has been active in opposition politics in his country since the age of 12. Many of his family and friends have been killed by government soldiers. Antonio delivered mail and vehicles to rebels fighting the Salvadoran government for six years, but he was forced to flee the country in 1986 when soldiers captured two of his co-workers and began looking for him. The co-workers never reappeared.

Antonio’s testimony stretched over more than a dozen afternoons. He said he fears he will be killed if he returns to El Salvador, and asked for political asylum.

After summarizing Antonio’s testimony and characterizing him as an honest and forthright witness, Judge Achtsam calmly denied his asylum plea. A gasp of incredulity arose from the spectators. Achtsam explained his decision: Antonio was not being threatened because of his political opinions. It is a crime in El Salvador to oppose the government; thus, Antonio is a criminal, and the government there has a right to hunt him down and punish him accordingly. The fact that the government systematically tortures and assassinates political dissenters is irrelevant Case closed.

“I couldn’t help but feel that Joe McCarthy had returned to life as an immigration judge,” Jahn said. “Achtsam’s decision basically says that a government has the right to persecute, torture, and even kill political dissenters.”

Proyecto will appeal the case to the equally conservative Board of Immigration Appeals, a process that could take years. In the meantime, Antonio joins the thousands of Salvadoran refugees who have been denied asylum in blatant disregard of the 1980 Refugee Act, which offers safe haven to anyone persecuted for their political beliefs.

Although refugees from many countries are stopped at the border and detained in the Valley, statistics reveal that those fleeing U.S.-supported governments are less likely to win asylum. For instance, less than four percent of all refugees fleeing the “democracies” of El Salvador and Guatemala received asylum last year, compared to nearly 84 percent of refugees fleeing the “Marxist Sandinista regime” in Nicaragua. Last year, Attorney General Ed Meese also ordered the INS to let Nicaraguan refugees work and travel while their asylum cases are pending.

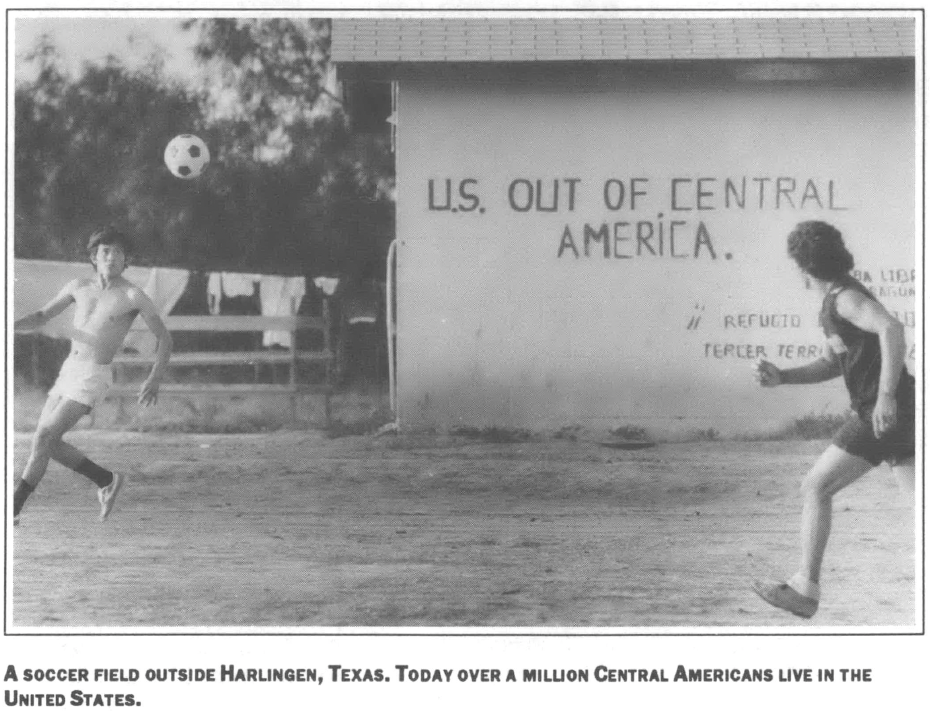

Yet the refugees continue to come. Indeed, three years after Ronald Reagan warned Americans that Harlingen is just a two-day drive from Managua, the only Central Americans to invade South Texas have been the hundreds of thousands of refugees driven here by U.S. foreign policy.

Although the immigration policies have succeeded in making life tough for Central American newcomers, forcing them to choose between starvation and political harassment in the Valley and starvation and political harassment back home, many eventually manage to escape the Valley and evade deportation, at least temporarily.

Ovidio, the Salvadoran campesino in the Proyecto Libertad waiting room, received permission to travel to New York and stay with a friend while his asylum application was being processed. Angela, the Guatemalan mother, had her family’s case transferred to Los Angeles and took a bus to join relatives there. The Salvadoran children and their uncles also managed to join their relatives in Canada after more than six months of legal hassles.

Such determination lies at the heart of what is happening in the Valley. In devising its get-tough immigration policies, it seems, the Reagan administration overlooked a critical point — if the U.S.-supported wars in Central America don’t stop, the flow of refugees won’t either.

Tags

Jane Juffer

Jane Juffer, an associate editor of the Pacific News Service, lived and worked in South Texas for two years. (1988)

Luz Guerra

Luz Guerra is an activist and organizer in Austin, Texas. She has worked nationally for the past three years as an educator and researcher focusing on Central America and Central American refugees. (1988)