Philosophies Clash in Supreme Court Race

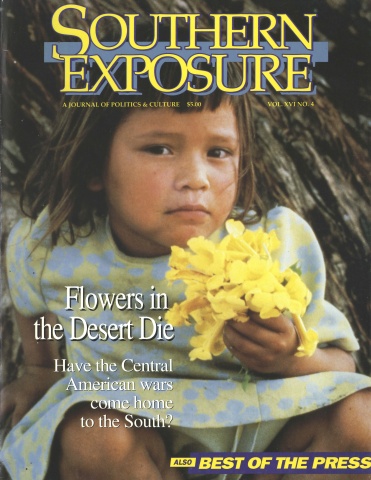

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 4, "Flowers in the Desert Die." Find more from that issue here.

West Virginia’s 1988 Supreme Court primary was the most expensive and hard-fought court election in state history. From January through June, Charleston Gazette reporter Norman Oder challenged the campaign rhetoric, examining the candidates records, and comprehensively analyzing the issues.

Charleston — The West Virginia Contractors Association has endorsed Kanawha Circuit Judges John Hey and Margaret Workman in the Democratic Supreme Court primary, as well as Republican Charlotte Lane. Why?

Responded executive director Mike Clowser: “Our board looked at the fact that the present Supreme Court spends more time making legislation and interpreting the law than acting upon the law itself.”

Whoops! Clowser checked a press release and corrected his language: “Our board felt the Supreme Court has overstepped its authority and is making law instead of interpreting it”

Hey says he will interpret law, not make law. So does Marion County Circuit Judge Fred Fox, another Democratic challenger. Lane says she will “interpret — not write — laws.” Workman says, “We expect judges to adhere to the law, following the law as it is, not as you’d like it to be.”

What’s the difference between interpreting law and making law?

None, says Robert Bastress, a professor at West Virginia University College of Law and a supporter of incumbent justices Darrell McGraw and Thomas Miller: “Every judge makes law, and if someone contends otherwise, that person is either lying or a fool. You have to take a constitution or statute that’s written in general terms and apply it to specific facts and that involves lawmaking.”

In CampaignSpeak, however, the words signify something. Candidates who say they will interpret law, not make it, suggest they might be less inclined to depart from previous judicial decisions to correct real or perceived wrongs. Also, they indicate they would be less inclined to invoke broad constitutional language to force state policy changes.

In other words, the challengers are suggesting a change in the court’s direction. The court’s detractors, pointing to its record on workers’ compensation and other labor issues, blame it for being antibusiness and infringing on the legislature’s powers.

In the past 12 years, the West Virginia Supreme Court with incumbent justices Miller and McGraw has heard hundreds more cases than its predecessor, in the process reshaping West Virginia law and the court’s role in making state policy. In the words of one of its supporters, Bill McGinley of the West Virginia Education Association, the court has been willing to “yank West Virginia into the 20th century.”

Miller, for example, has prepared a list of more than 50 decisions he has written, including cases upholding people’s rights to sue contractors for defective construction, preventing firing of whistleblowing workers, and providing that the value of a woman’s work as a homemaker be considered in a divorce settlement. Before the 1970s, says West Virginia University professor Franklin Cleckley, the court often did not look to other state courts for guidance. In many areas, Cleckley says, West Virginia did not have a developed body of law.

The court has invoked the broad language of the state constitution to decide certain questions previously left to other branches of government. In 1979, the court ordered Special Judge Arthur Recht to develop standards to meet the state constitution’s guarantee of a “thorough and efficient education.” The legacy of the “Recht decision” — equalization of funding — is still being fought in the courts and legislature.

The court has been willing to take broad legislative language and interpret it creatively. In 1983, a few years before the country awakened to the homeless issue, McGraw wrote a decision making West Virginia the first state to order funding of emergency food, shelter, and medical care for the homeless. Justice Richard Neely dissented angrily, saying the court was injecting itself into an issue outside its powers.

In a state where the legislature often has trouble passing a budget, the Supreme Court has taken on an increasingly high profile in deciding issues. For certain interest groups, the court race, with two candidates winning 12-year terms, seems more important than the governor’s race. With Miller, McGraw, and Justice Thomas McHugh forming a 3-2 majority on several issues, the United Mine Workers and the West Virginia Education Association warn, “We’re only one justice away from injustice.”

Tipping the Balance

A self-described “people’s judge,” McGraw, who grew up in Wyoming County coal country, says court systems have traditionally favored the powerful. He is admired and detested for his open embrace of unions and attacks on corporate evil. By denouncing right-to-work laws and calling a Chamber of Commerce meeting a “right-to-work rally,” McGraw has violated judicial ethics, his opponents say.

Miller, though he often votes with McGraw, does not proclaim the same brand of populism, saying his satisfaction comes when he reaches the appropriate judicial opinion through research. As a trial lawyer for 20 years, Miller recalls, his greatest frustration was finding a Supreme Court unwilling to hear his appeals and update state law.

“I think the real debate is whether you want a court that is going to maintain a liberal bent, for lack of a better word, or whether you want a court that’s going to be more deferential to legislative choice and the status quo,” says Bastress. “This is a court that is not afraid to push the law in the direction it sees is most just.”

Much of the time, the court acts with little controversy, but when existing law does not specify a solution, the judges — and their philosophies — weigh cases in other jurisdictions and split on the right policy: Can a coal miner sue his employer? Does a teacher deserve a grievance hearing? Is cancer compensable under workers’ compensation? Is the property-tax system unfair?

The coal operators, businessmen, and corporate lawyers backing Fox, Hey, and Workman obviously hope the candidates will help “balance” the court, making it more sympathetic to business. The five challengers — the three Democrats and Republicans Lane and Jeniver Jones — have each indicated they would be more likely to vote with the incumbents Neely and William Brotherton.

Though judicial candidates are prohibited from commenting on pending judicial issues, some have criticized past court decisions. Nearly every candidate denounces McGraw’s decision to allow judges to claim previous governmental service, including his own work as a janitor at West Virginia University, to qualify for a pension. Few McGraw supporters defend the opinion on legal grounds. Even Miller, in a later opinion, said part of the decision should have been left to the legislature — which later modified the judicial pension system. Lane and Fox think the court should have left the Recht school-funding case to the legislature, saying the case was an example of the proper result by improper means.

Fox and Hey, both known for stiff sentencing, cite a Miller decision that says judges cannot imprison people for criminal contempt of court without a jury trial. That decision provides greater protection to individuals than the U.S. Constitution. Hey says it has made his job harder, that he was prevented from throwing a defendant who cursed him into jail. Miller says a trial judge’s power to imprison someone in such a case is a dangerous weapon because the judge cannot be objective.

Nearly all the challengers have called the court’s record on workers’ compensation anti-business, while lawyers for workers say the court is needed to counteract the biased Workers’ Compensation Appeals Board appointed by Republican Governor Arch Moore. More than one-third of the court’s docket in 1987 was workers’ compensation cases. The Supreme Court said the board was wrong in 307 out of 351 appeals by employees. On the other hand, the court refuses to hear more than half the cases presented, effectively denying them.

Nowheresville

McGraw calls his Democratic opponents “Republicans” and warns that electing any of them will take the court back to “nowheresville,” a time when the court closed its doors to people seeking relief. In 1976, the court heard only 75 cases. It heard 775 last year, though more than a third were workers’ compensation appeals. McGraw and Miller say they are proud to be on an “active” court willing to consider issues and change the law. Workman doesn’t agree with that term. Her objection, she says, is not that the judges hear more cases, but that they are “activist.”

Says Fred Holroyd, a lawyer who is a labor consultant to management, “You’ve got the Supreme Court taking all the cases in the country and saying, ‘Here are the most liberal and we want to put them in West Virginia’ . . . when we ought to be going the other way.”

Fox says of the court’s record, “I think the idea that the Supreme Court hears more cases is probably good. But, by the same token, I think you can go overboard.” He adds, “I agree with them on a lot more cases than I disagree with them.” However, Fox believes the court is “far to the left in terms of being pro-worker and anti-business.”

Hey paints himself as the harshest critic of the court’s record. Alone among the candidates, Hey calls the Supreme Court the prime culprit in the state’s economic decline — an assertion few court critics have made. He believes the pre-1976 court did a good job. “I think they were performing the proper functions of an appellate court. I don’t think this court is. I think this court is totally politicized,” he says.

Making Law

Where to draw the line between judging and legislating? In 1981, Neely, no great friend of the court majority, wrote a book on the topic. “It is a book about whether courts should make law in the broadest, grandest, political sense,” Neely wrote in How Courts Govern America. “The reason that this book must be written is that courts do, in fact, make law in what often appears to be a lawless process.”

In interviews, Hey, Fox, Workman, and Lane have each said the responsibility for writing laws is up to the legislature. “Even if they were the lousiest legislators in the world . . . that does not give the judiciary the right to occupy their powers,” says Workman.

But that’s not the way it works in the real world, Neely writes. The classic example of a court “making law” was the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision outlawing school segregation. And in the 1960s, the U.S. Supreme Court consistently “made law” by interpreting the Constitution to give criminal suspects more rights, such as requiring police officers to tell them they had the right to remain silent and consult a lawyer.

Legislatures, faced with a limited agenda, leave certain issues to the courts, Neely points out. In reviewing common law handed down in previous judicial decisions, courts may look at changing societal standards. In 1963, the California Supreme Court was the first to decide that people injured by defective products had to prove only that the product was defective — rather than that it was made negligently.

By 1976, 37 state supreme courts and four legislatures had made similar decisions. It took West Virginia until 1979, when Miller wrote a decision in Morningstar vs. Black and Decker. Backers of the present justices cite cases like this to show how slow the pre-1976 court was to accept change.

In the primary, Thomas Miller led the field, followed by Margaret Workman. Darrell McGraw, who placed third, lost his seat on the court. Miller and Workman went on to win in November.

Tags

Norman Oder

Norman Oder wrote this story as a reporter at The Gazette in Charleston, West Virginia. He will enter Yale Law School this fall on a one-year fellowship for journalists. (1989)

Charleston Gazette (1988)