La Victoria en Virginia

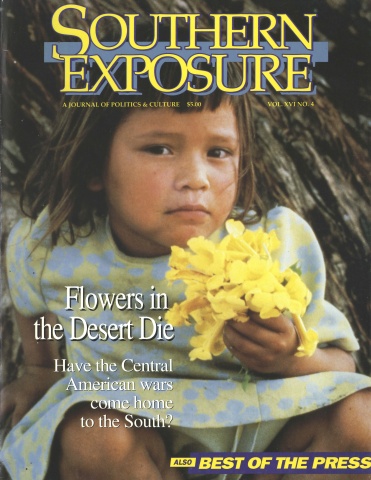

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 4, "Flowers in the Desert Die." Find more from that issue here.

Salsa music fills the air. A tortilla truck makes it deliveries. Families gather to share a potluck supper of their favorite Latin American dishes. And everyone converses in Spanish.

The time is 1986. Although it has the feel of a bustling Central American village, the setting is Lee Gardens, then the largest low-income apartment complex in Arlington, Virginia.

Two years ago, 87 percent of the estimated 3,000 inhabitants of these 1940s garden apartments were Hispanic, most of them recent refugees from Central America. Today the demographics have changed considerably: The 960-unit complex has been sold to a Maryland developer and is being renovated and rented to more upscale North Americans. Most of the Latinos have been evicted and have moved on — some back to their homelands, many more to shabbier homes and apartments in the outer suburbs. Although many have jobs in nearby restaurants and hotels, they can’t afford metropolitan-area rents on wages of less than $5 an hour.

But thanks to an unusual alliance of Hispanic tenants and local civic leaders in this Southern suburb of Washington, D.C., more than a third of the newly upgraded apartments have been set aside for low-to-moderate income households. As a result, rent subsidies will allow 200 impoverished families — about 135 of them Latinos — to live in comfortable modernized apartments and remain in this close-knit complex. Eventually, another 164 units will also be available at lower-than-market rates.

“I feel so at home here,” says Juliete Nelson, former president of the Lee Gardens Tenants Association, who moved to the area from Panama in 1982. She faced eviction until the tenants group organized and convinced the Arlington Housing Corporation to buy back 38 percent of the units from the developers and make them available at affordable rates.

“It’s not just because of the Hispanic population,” says Nelson. “The whole complex lives like a community, not like strangers. It’s like an extended family. I’ve learned that you just have to get involved in the community in which you live.”

Today the rent-subsidized units are identical to the other apartments in the renovated complex, except they do not come with dishwashers, washers, and dryers. ‘These are the nicest subsidized units I have seen in Arlington County,” says Judith Arandes, a Puerto Rican immigrant who now works as relocation specialist for the Arlington Housing Corporation.

Still, the 364 units purchased by the non-profit housing development organization won’t help all of the nearly 1,000 low-income families that lived at Lee Gardens before the complex was sold. What’s more, federal regulations governing income eligibility for the rent-subsidized units don’t take into account that many Hispanics are also supporting family members back in their homelands. As a result, all but 150 households have been forced to look elsewhere for shelter. Most of them have ended up at rundown complexes where landlords allow tenants to overcrowd the apartments — the only way that many can afford the rent. And some have already been evicted again as the few remaining affordable apartment complexes in the area are sold off to developers.

No Don Quixotes

Even this partial victory at Lee Gardens wouldn’t have been possible without hard-fought achievements won earlier by another group of Latino tenants in nearby Alexandria. It all started three years ago when residents of Dominion Gardens received eviction notices after that complex was sold and renovated. At the time, Virginia state law required landlords to give only a 30-day notice prior to eviction.

Magda Lopez Gotts, a Guatemalan who has lived in northern Virginia for 13 years, thought such short notice was unfair. She began attending public hearings and talking to her neighbors — 85 percent of whom were Hispanic, and most of whom had made the South their home. Eventually, they lobbied successfully for a state law that requires that all tenants be informed of hearings affecting the status of their apartments and that they be notified 120 days prior to eviction when the property is sold.

Although Gotts and the tenants of Dominion Gardens were eventually forced to move, their legislative gains gave low-income residents at nearby Lee Gardens time to organize against their pending evictions. And Gotts was on hand to do whatever she could for her Hispanic neighbors in nearby Arlington.

“I was with tenants till midnight seven nights a week and on the phone all the time,” says Gotts, who now operates a small child-care program in her rented duplex in Alexandria. “It was important to get together with the white North Americans, the blacks, and the Hispanics. It was a lot of work.”

The efforts of Gotts and others paid off. Over 200 residents of Lee Gardens crowded into hearings at city hall to demand that local and state officials do something to reverse the erosion of affordable housing stock that began under the Reagan administration. Tenants — many of whom could neither read nor write English — joined with civic and church leaders in pressing for subsidized units and relocation payments for families forced to move. Together they filed a class-action suit demanding the preservation of affordable housing for low-income residents.

Before long their stories were being told under headlines in The Washington Post.

“People in the housing field in Arlington thought we were crazy,” recalls Elaine Curry-Smithson, executive director of the Tenants of Arlington County, a tenants organizing group. “In the beginning many, many people said, ‘You’re fools, you’re Don Quixotes off chasing windmills.’”

Although tenants didn’t win all of their demands, Curry-Smithson says, they did secure a larger share of low-income housing for tenants than in any other previous local organizing effort. And — like their Alexandria neighbors before them — their achievements have set important precedents for others who continue to work for affordable housing.

“The housing crisis is booming here,” says Gotts, the tenant organizer from Guatemala who was homeless for a short time after she was evicted from Dominion Gardens. “But tenants here forced the local and federal government to become more aware of this acute problem and not close their eyes any more. Maybe other tenants will do just like Lee Gardens tenants did. And maybe they can save a few more apartments.”

It is the determination of Central American refugees like Gotts who have settled in to this Southern community just across the Potomac River from the White House that has helped them achieve landmark gains in the ongoing battle to address the plight of the poor and homeless. They took on developers and local officials and won — and in the process they taught their North American neighbors a lesson in community organizing.

“There is a Latino phrase,” recalls Juliete Nelson. “It is ‘The last thing that dies with us is hope.’”

Tags

Dee Reid

Dee Reid is a journalist living near Pittsboro who frequently writes about rural and environmental issues. A former reporter and managing editor for The Chatham County Herald, she has received six North Carolina Press Association awards in the past four years. (1983)