This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 4, "Flowers in the Desert Die." Find more from that issue here.

Houston, Texas — Driving west, away from the city, fragments of architect Philip Johnson’s post-modem skyline appear then disappear in the rearview mirror. To the right is the Greenway Plaza office park, austere architectural modernism at its narcissistic worst — distorted images of one glass tower reflected on the sides of another — and another. On the left, the odd geometry of the Houston Post building, designed, according to the city’s finest architect, Howard Barnstone, to be appreciated at a passing glance at 50 miles an hour. Then, on the right and in the distance, before the freeway frontage completely gives way to car dealerships and strip development, the Transco Tower — the huge vertical art-deco shaft that dominates the city’s southwest skyline.

At 50 miles an hour, or at the painfully slow pace by which most commuters make their ways toward the predominantly white, tract-house suburbs that encircle the city, few recognize, even after the freeway bends from west to southwest, that they have just passed through one of the largest Central American communities in the South. A community they might discover, if only they would turn south at the Bellaire exit and continue some 10 blocks to the sprawling, corporate-owned Central American mercado at the comer of Bellaire and Hillcroft.

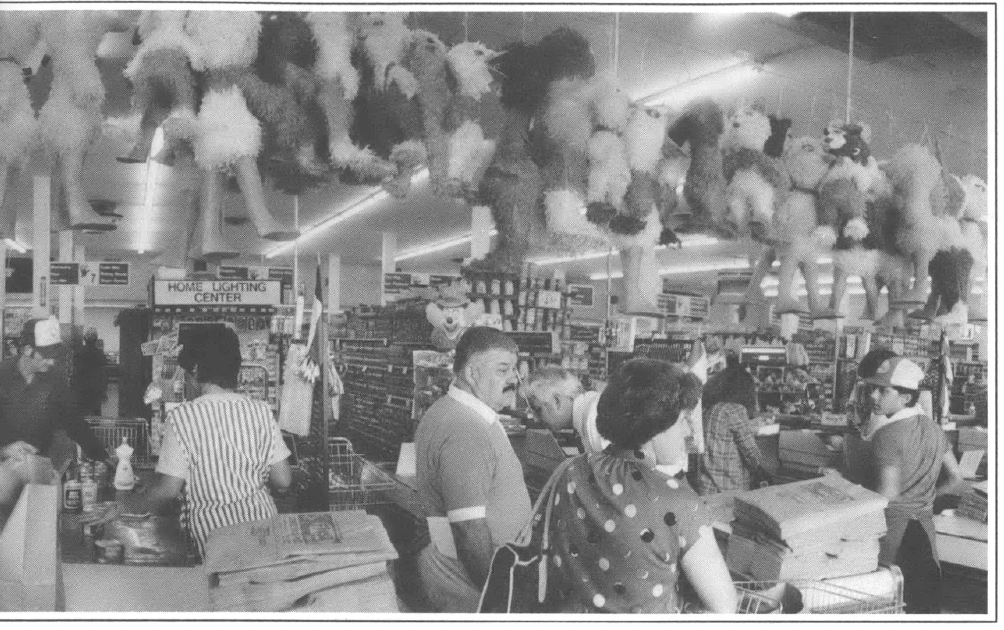

The huge Fiesta market anchors the city’s new Hispanic community, here in the heart of what 10 years ago was white middle-class Houston. The neighborhood is a small Hispanic town all clustered around and in the market, which includes a bank, a dentist’s office, an optician, a travel agency, and a Western Union office where money orders and giros — money wired to foreign countries — are among the most requested services.

In the parking lot, on spaces rented from the Fiesta market chain, are a dozen estanquillos — booths where vendors sell cheap clothing, leather goods, furniture, jam-boxes, cassette tapes, and cheap art. (On this particular afternoon, a recumbent Marilyn Monroe hangs framed above The Last Supper.) A Reparacion de Calzado — shoe repair — stands across the street from the Clinica del Sol medical center. A half-block to the north is La Caseta — a long distance phone center with private booths and bilingual operators. Here there is everything, more than a consumer would ever find in the center of San Salvador.

Although there are an estimated 100,000 Salvadorans living in Houston today, the crowded market offers the only clear evidence of their growing numbers. “If you don’t go to Fiesta, you won’t see them,” said Richard Grimes, a professor of public health at the University of Texas. “They’re an invisible population; most of Houston doesn’t know that they’re here.”

Adios, Singles Scene

Last year, Grimes directed two graduate students, Ximena Umitria-Rojas and Melvin Prado, who conducted a door-to-door survey to determine public health needs in southwest Houston. What they documented is as rapid a demographic change as has ever occurred in a Houston neighborhood. In a matter of four to five years, this corner of southwest Houston has become a small Central American city. According to the study, 13,500 Hispanics live within the one square mile surveyed — and 36 percent of that number is Salvadoran.

The survey also confirmed what the management of the Fiesta chain already realized: the Central American newcomers are not young, single men looking for casual work. According to Grimes, 55 percent of the population is male, 45 percent is female. “Twenty percent of this group,” Grimes said, “are American citizens.” Children born to parents living in exile.

There is, in all of this, an odd demographic irony. These two-story brick-veneer apartments, built 25 years ago around small courtyards and swimming pools, were never intended for the Salvadoran, Mexican, Guatemalan, and Honduran children who spill out of the yellow Houston Independent School District buses at the end of each weekday, then scramble for the access-gates at places like Colonial Gardens, Lion’s Gate, Clarewood Gardens, and Renwick and Trafalgar Squares. Nor were they intended for the few black families who are also changing the character of what was previously an almost exclusively white neighborhood.

“In 1980, this neighborhood was hot,” one apartment manager said. “It was Houston’s singles scene where most of the young people who used to work for the oil companies lived. Then, in 1982, the bottom fell out and the vacancy rate went out of sight.”

According to Jim Sandford, who directs an apartment owners association, most of the vacated apartments became properties of the banks and lending institutions that had financed them. “The banks demanded that they fill the apartments to bring in some money,” Sandford said. “So rents went down and there were no more credit checks.”

At the same time, other demographic pressures were at work in Central America, particularly El Salvador. “In 1981, the war got very hard,” said one young man from the Department of Morazan. “I was in Los Angeles and I tried to return to help my family. When I couldn’t even get into the country, I came here. My parents got out of El Salvador, too.”

“My family measures our time here by the years of the Reagan Administration,” said a young woman from the El Salvador’s Department of Usulutan. “In 1981, my mother and father came to Brownsville. Then they moved to Houston. In 1983 I came to Los Angeles, the only place the coyote would take me. Then, by plane, I came to Houston. Later my sister and brothers came.”

If her citizenship papers had been completed in time for the presidential election, the young woman added, she would have voted for Michael Dukakis. Only her parents still talk of someday returning to El Salvador, where they once owned a small business.

Most agree with the young woman. At Holy Ghost Church, a dozen women have gathered to receive clothing provided through the parish and Casa Juan Diego, a shelter for Central Americans. Most are mothers under 20. I asked the same question of all of them: “Were the war to end and the economy to improve, would you return to your home?” One woman defined the consensus. “Si. Pero no mas pa’ ir y regresar.” Yes, but only to go and to return.

Most will never go. Unless, that is, they are apprehended by the INS and deported. For many, the marginal lives they live here are better than anything they have ever known in their homeland. And there are children. But Houston’s depressed economy, and the new federal sanctions against employers who hire undocumented workers, assure that many will continue to live at the margin.

Out of the Shadows

As more and more Salvadorans settle in southwest Houston, some are beginning to organize. “It’s time to start thinking in terms of empowerment,” said Mark Zwick, founder of Casa Juan Diego. Zwick, who is working with community members to organize an empowerment project, argues that improvements in living conditions will have to come from within the community, from below — a fundamental precept of the religious activist movement known as liberation theology. “Knowledge is power,” Zwick said, “and that is where we will begin.”

The empowerment project will address tenant-landlord relations, workers’ rights, fundamental legal protections, and problems with schools, the post office, and the police. It is one of several grassroots movements developing in the Salvadoran community.

Others take as their model the communidades de base or “base communities” that have reinvented the Catholic Church in Latin America. At Holy Ghost Parish, a “scripture sharing” group meets to discuss how the Bible applies in a practical way to day-to-day life. At nearby St. Anne’s, a Catholic parish once so chic and wealthy that its parishioners almost considered themselves Episcopalians, a 30-year-old Salvadoran woman described a similar group she helped organize:

“We study the Word of God . . . to reestablish our identity, to recapture our dignity. Living like this, without work, without documents . . . we don’t even know who we are. In Salvador, I worked in a religious community. Here it is important, too. If we use the scripture and our discussion, maybe we can come out of the shadows.”

“It’s not easy,” said Tom Picton, a priest at Holy Ghost “There is no political power because there is no political base, no bloc of voters.”

Cesar, a Salvadoran who works for a sanctuary and relief organization in Houston, agrees. “When I lived in New York,” he said in perfect English, “there was some political organizing and working for political rights. But here, there is not so much of this.” An articulate, almost full-time activist whose immediate family is safe in Europe, Cesar said that he spends much of his time providing basic needs like beds, food, and assistance with immigration problems. On the day we spoke, the INS raided an informal labor pool on the street comer near Casa Bill Woods, where Cesar works.

“The city is only beginning to realize that they are out there,” Lois O’Connor said of the Central Americans. O’Connor, who works for Houston City Councilman John Goodner, said she was surprised when a recent request for a part-time, city-funded clinic in the district was approved. “I’m used to being told no,” O’Connor said. Goodner’s office, according to O’Connor, has also persuaded the city administration to locate a federal children’s nutrition office in the district. And a storefront police station is also in the works to deal with the increase in violent crime in the past two years.

According to Richard Grimes, who lives in southwest Houston, much of the crime came with the employer sanctions in the immigration reform law. ‘There was no prostitution until other legitimate sources of employment were cut off,” he said. “Now you can find prostitutes in the community — and drug dealing.”

Zwick said that at Casa Juan Diego there are now more signs of families in stress, “domestic crises, alcoholism, battered women.” The shelter, which was established to house homeless men, now operates a program for battered women. And Carecen, a local legal services organization, recently hired a counselor to assist traumatized families, particularly women.

No Offices

Domestic crises result, in part, from an odd distribution of labor among Central American families. While men spend mornings at informal comer labor pools looking for casual work, many women, who can always find domestic work, leave their families each night to clean the huge office towers where the city earns its living.

“The [office] work is very hard and degrading,” said a young woman who had started medical school just when the university in San Salvador was closed by the government. “What they demand of the women and the way they are treated is not fair. And some women take drugs to stay awake.” She now cleans houses every day. “But no offices,” she said.

Although the swelling number of Salvadorans is altering the demographic landscape of the city, Central American residents are largely ignored in the official business of the city and county. Local political campaigns in the district are conducted entirely in English. And though Houston Mayor Katherine Whitmire has worked to build inroads into the large and politically active Asian community, no elected leader has connected with the large Central American community.

O’Connor expects it will take another generation before Central Americans have a voice in local politics, but others disagree. “A large number of Central Americans are residents now,” said Frances Tobin, a local immigration attorney. “And in five years many of them will be qualified to vote. That’s when the biggest changes will come.”

“Right now we have no community,” a 60-year-old Salvadoran man said. “What we have is una red — a network — to get help and help each other.”

In El Salvador, this man and his family operated a small business. Here in Houston, everyone in the family either works or studies. In eight years, they have moved from the Casa Juan Diego into an apartment, then into the three-bedroom tract home where they now live in southwest Houston. When he is not working — either as a carpenter or mechanic — this former shopkeeper and his wife do volunteer work in the Salvadoran “network.” One son is married and in another state. One daughter has organized and teaches a Central American group at a Catholic church. Another hopes to resume her medical studies here someday. For now, she cleans houses every day. “But no offices.”

Southwest Houston is no one’s community. Like Los Angeles, it is an urban place, a place designed to accommodate the two-car family. So now, at night, when most families have returned to their apartments, the parking areas remain mostly empty — of cars, that is. They are often filled with shopping carts. This is, after all, the first pedestrian culture that southwest Houston has known. Women here navigate shopping carts loaded with children, groceries, and clothing through residential streets and thoroughfares where no one ever anticipated the need for sidewalks. And in the city where Howard Barnstone reinvented residential architecture to accommodate the automobile, distances between homes and schools and stores often seem immense.

So while in the inner city the shopping cart has become the symbol of the nation’s homeless, here it has come to represent something else: the newly arrived immigrant.

Tags

Louis Dubose

Lou Dubose is editor of The Texas Observer, and Ellen Hosmer is editor-at-large of Multinational Monitor. Names of Mexican workers quoted in this story have been changed to protect them from possible reprisals by their employers. (1990)